Volume 3, Issue 2, Summer 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collections Development Policy

Collections Development Policy Harris Museum & Art Gallery Preston City Council Date approved: December 2016 Review date: By June 2018 The Harris collections development policy will be published and reviewed from time to time, currently every 12-18 months while the Re-Imagining the Harris project develops. Arts Council England will be notified of any changes to the collections development policy, and the implications of any such changes for the future of the Harris’ collections. 1. Relationship to other relevant policies/plans of the organisation: The Collections Development Policy should be read in the wider context of the Harris’ Documentation Policy and Documentation Plan, Collections Care and Conservation Policy, Access Policy Statement and the Harris Plan. 1.1. The Harris’ statement of purpose is: The Re-Imagining the Harris project builds on four key principles of creativity, democracy, animation and permeability to create an open, flexible and responsive cultural hub led by its communities and inspired by its collections. 1.2. Preston City Council will ensure that both acquisition and disposal are carried out openly and with transparency. 1.3. By definition, the Harris has a long-term purpose and holds collections in trust for the benefit of the public in relation to its stated objectives. Preston City Council therefore accepts the principle that sound curatorial reasons must be established before consideration is given to any acquisition to the collection, or the disposal of any items in the Harris’ collection. 1.4. Acquisitions outside the current stated policy will only be made in exceptional circumstances. 1.5. The Harris recognises its responsibility, when acquiring additions to its collections, to ensure that care of collections, documentation arrangements and use of collections will meet the requirements of the Museum Accreditation Standard. -

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch Für Europäische Geschichte

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch für Europäische Geschichte Edited by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Volume 20 Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe Edited by Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Edited at Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Founding Editor: Heinz Duchhardt ISBN 978-3-11-063204-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063594-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063238-5 ISSN 1616-6485 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 04. International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number:2019944682 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published in open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and Binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Cover image: Eustaţie Altini: Portrait of a woman, 1813–1815 © National Museum of Art, Bucharest www.degruyter.com Contents Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Introduction 1 Gabriel Guarino “The Antipathy between French and Spaniards”: Dress, Gender, and Identity in the Court Society of Early Modern -

Use and Applications of Draping in Turkey's

USE AND APPLICATIONS OF DRAPING IN TURKEY’S CONTEMPORARY FASHION DUYGU KOCABA Ş MAY 2010 USE AND APPLICATIONS OF DRAPING IN TURKEY’S CONTEMPORARY FASHION A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF IZMIR UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS BY DUYGU KOCABA Ş IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENTOF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF DESIGN IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES MAY 2010 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences ...................................................... Prof. Dr. Cengiz Erol Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Design. ...................................................... Prof. Dr. Tevfik Balcıoglu Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adaquate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Design. ...................................................... Asst. Prof. Dr. Şölen Kipöz Supervisor Examining Committee Members Asst. Prof. Dr. Duygu Ebru Öngen Corsini ..................................................... Asst. Prof. Dr. Nevbahar Göksel ...................................................... Asst. Prof. Dr. Şölen Kipöz ...................................................... ii ABSTRACT USE AND APPLICATIONS OF DRAPING IN TURKEY’S CONTEMPORARY FASHION Kocaba ş, Duygu MDes, Department of Design Studies Supervisor: Asst. Prof. Dr. Şölen K İPÖZ May 2010, 157 pages This study includes the investigations of the methodology and applications of draping technique which helps to add creativity and originality with the effects of experimental process during the application. Drapes which have been used in different forms and purposes from past to present are described as an interaction between art and fashion. Drapes which had decorated the sculptures of many sculptors in ancient times and the paintings of many artists in Renaissance period, has been used as draping technique for fashion design with the contributions of Madeleine Vionnet in 20 th century. -

Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018

The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Front Cover Image: Textile Detail of an Evening Dress, circa 1950s, Maker Unknown, Middlesex University Fashion Collection, London, England, F2021AB. The Middlesex University Fashion Collection comprises approximately 450 garments for women and men, textiles, accessories including hats, shoes, gloves, and more, plus hundreds of haberdashery items including buttons and trimmings, from the nineteenth century to the present day. Browse the Middlesex University Fashion Collection at https://tinyurl.com/middlesex-fashion. The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Editor–in–Chief Jennifer Daley Editor Scott Hughes Myerly Proofreader Georgina Chappell Published by The Association of Dress Historians [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org Copyright © 2018 The Association of Dress Historians ISSN 2515–0995 Online Computer Library Centre (OCLC) accession #988749854 The Journal of Dress History is the academic publication of The Association of Dress Historians through which scholars can articulate original research in a constructive, interdisciplinary, and peer reviewed environment. The Association of Dress Historians supports and promotes the advancement of public knowledge and education in the history of dress and textiles. The Association of Dress Historians (ADH) is Registered Charity #1014876 of The Charity Commission for England and Wales. The Journal of Dress History is copyrighted by the publisher, The Association of Dress Historians, while each published author within the journal holds the copyright to their individual article. The Journal of Dress History is circulated solely for educational purposes, completely free of charge, and not for sale or profit. -

Welcome New Cadets at the Ice Cream Social Submitted by the U.S

Room dedication to Gen. David Petraeus, 7 p.m. Friday at Thayer Hotel. OINTER IEW ® PVOL . 67, NO. 24 SERVING THE COMMUNITY OF W VE S T POINT , THE U.S. MILITARY ACADEMY JUNE 24, 2010 Exuding confidence Before the firsties and cows can lead the yearling class through Cadet Field Training this summer, they must first complete a two-week block of training to prepare them for their leadership roles. To start, the cadets revisited the water confidence course they endured when first encountering CFT. They negotiated the Slide for Life, climbing a 75-foot tower then riding down a steel cable on a trolley for 150 feet before dropping into the water. The cadets also traversed an 80-foot beam suspended 25 feet above water. The cadets also undertook training in blocks of instruction to include introduction to patrolling, land navigation, urban operations and a leadership academy, where they learned the fundamentals of being noncommissioned officers in the Corps of Cadets. MIKE STRA ss ER /PV Welcome new cadets at the Ice Cream Social Submitted by the U.S. on the USCC Web Page (www-internal. Criteria for the Ice Cream Social are privileges boundary, then this person is Corps of Cadets office uscc.usma.edu) beginning July 21. More as follows: authorized to take cadet(s) to his or her information about the sponsorship program is • Rank: Be a military rank of sergeant first residence only. Personnel hosting new cadets The U.S. Corps of Cadets office will available in the Sponsors’ Handbook. class (E-7) to sergeant major (E-9), warrant may use academy common areas such as conduct New Cadet Visitation Day, or the Ice Participation of Families from the West officer (W-01 and above) and captain (O-3) picnic tables located throughout post. -

GEORGE W. BROWN the BRUNSWICK Hotel Lenox

BOSTON, MASS., FRIDAY. APRIL 14. 1905 1 0 GEORGE W.BROWN SHIRTINGS FOR 1905 ARE READY Copley Square All the Newest Ideas for.Men's Negligee and Nvlercbant Summer Wear in Hotel SHIRTS tailor Made from English, Scotch and French Fabrics. Huntington Aoe. & Exeter St. Private Designs. BUSINESS AND DRESS 110 TREMONT STREET SUITS PATRONAGE of "Tech" students $1.50, $2.00, $3.50, $4.50, $5.50 and solicited in our Cafe and Lunch Upward Room All made 27he attention of Secretaries Makes up-to-date students' in our own workrooms. Consult us to ana know the Linen, the Cravet and Gloves to Wear. Banquet Committees of Dining clothes at very reasonable Clubs, Societies, Lodges, etc., is GLOVES called to the fact that the Copley Fownes' Heavy Square prl;r., Street Gloves, hand Hotel has exceptionally I lStitched, $1.50. Better ones, $2.00, ood facilities $2.50 and $3.00. Men's and Women's for serving Breakfasts, Luncheons or Dinners and will cater NECKWEAR out of the ordinary-shapes strictly especially to Suits and Overcoats from $35 new-8-1.00 to $4.50. this trade. Amos H. Whipple, Proprietor This is the best time of the ENTIRE YEAR, N oy s Oi /ros.' Summer Streets, for you to have your FULL DRESS, Tuxedo, Boston, U. S. A. or Double-Breasted Frock Suit made. We make a Specialty of these garments and make Special Established I874 Prices during the slack season. Then again, we SPRING OPENING have an extra large assortment at this time, and DURGIN, PARK & CO,. -

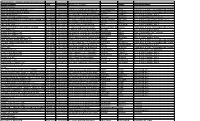

New Licenses

New Licenses - ALLIssued from 01/01/2021 to 09/01/2021 as of 09/01/2021 8:13 am Business Name Lic # IssuedDate Business Location Owner Type of Business Alcohol License 1800 MEXICAN RESTAURANT, LLC ALC13606 06/28/2021 5296 New Jesup Hwy Brunswick DURAN MARIN RAUL Liquor Beer & Wine Consumption On Premis BEACHCOMBER BBQ & GRILL ALC14200 08/25/2021 319 Arnold Rd St Simons Island PARROTT THOMAS Liquor Beer & Wine Consumption On Premis BPR BRUNSWICK LLC ALC13776 04/07/2021 116 Gateway Center Blvd BrunswickPATEL PANKAJ Beer & Wine Package Sales COBBLESTONE WHOLESALE ALC14190 08/25/2021 262 Redfern Vlg St Simons Island STEGER RHONDA Wine Consumption On Premises CRACKER BARREL OLD COUNTRY STORE, INC.ALC14060 07/26/2021 211 Warren Mason Blvd Brunswick CHRISTENSEN WILLIAM Beer & Wine Consumption On Premises DOLGENCORP,LLC ALC13837 05/13/2021 461 Palisade Dr Brunswick GILLIS MATIE Beer & Wine Package Sales DOLGENCORP,LLC ALC13923 05/12/2021 25 Cornerstone Ln Brunswick REID FEATHER Beer & Wine Package Sales DOROTHY'S COCKTAIL & OYSTER BAR ALC13687 03/19/2021 12 Market St St Simons Island AUFFENBERG JR. DANIEL Liquor Beer & Wine Consumption On Premis ELI CAIRO LLC ALC13631 01/07/2021 72 Altama Village Dr Brunswick MAZON ELI Beer & Wine Package Sales FRANCIE & MARTI LLC ALC13953 07/08/2021 295 Redfern Vlg A St Simons Island TOLLESON MARTI Wine Consumption On Premises FRANCIE & MARTI LLC ALC13954 07/08/2021 295 Redfern Vlg A St Simons Island TOLLESON MARTI Wine Package Sales GEORGIA CVS PHARMACY, LLC ALC13711 03/23/2021 1605 Frederica Rd St Simons Island -

Liz Falletta ______

Liz Falletta _____________________________________________________________________________________ CONTACT University of Southern California Phone: (213) 740 - 3267 INFORMATION Price School of Public Policy Mobile: (323) 683 - 6355 Ralph and Goldy Lewis Hall, 240 Email: [email protected] Los Angeles, CA 90089-0626 Date: January 2015 TEACHING University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA APPOINTMENTS Price School of Public Policy Associate Professor (Teaching), July 2014 – present Assistant Professor (Teaching), January 2009 – May 2014 Clinical Assistant Professor, July 2007 – December 2008 Lecturer, June 2004 – June 2007 Iowa State University, Ames, IA College of Design, Department of Architecture Visiting Lecturer, January 2003 – May 2003 University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA School of Architecture and Urban Design Co-Instructor (with Mark Mack), October 2002 – December 2002 Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc), Los Angeles, CA Instructor, August 2000 – December 2000 Associate Instructor, June 2000 – August 2000 EDUCATION University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA Master of Real Estate Development, 2004 Southern California Institute of Architecture, Los Angeles, CA Master of Architecture, 2000 Washington University, St. Louis, MO Bachelor of Arts in Architecture, Philosophy Minor, magna cum laude, 1993 COURSES University of Southern California TAUGHT Price School of Public Policy Design History and Criticism (RED 573), Summer 2004 – present Community Development and Site Planning (PPD -

Humour Number 20, February 2015 Philament a Journal of Arts And

Philament Humour A Journal of Arts Number 20, and Culture February 2015 Philament An Online Journal of Arts and Culture “Humour” Number 20, February 2015 ISSN 1449-0471 Editors of Philament Editorial Assistants Layout Designer Chris Rudge Stephanie Constand Chris Rudge Patrick Condliffe Niklas Fischer See www. rudge.tv Natalie Quinlivan Tara Colley Cover: Illustrations by Ben Juers, design by Chris Rudge. Copyright in all articles and associated materials is held exclusively by the applica- ble author, unless otherwise specified. All other rights and copyright in this online journal are held by the University of Sydney © 2015. No portion of the journal may be reproduced by any process or technique without the formal consent of the editors of Philament and the University of Sydney (c/- Dean, Faculty of Arts and Sciences). Please visit http://sydney.edu.au/arts/publications/philament for further infor- mation, including contact information for the journal’s editors and assistants, infor- mation about how to cite articles that appear in the journal, or instructions on how submit articles, reviews, or creative works to Philament. ii Contents Editorial Preface Chris Rudge, Patrick Condliffe 1 Articles Mika Rottenberg’s Video Installation Mary’s Cherries: A Parafeminist “dissection” of the Carnivalesque 11 Laura Castagnini Little Big Dog Pill Explanations: Humour, Honesty, and the Comedian Podcast 41 Melanie Piper Arrested Development: Can Funny Female Characters Survive Script Development Processes? 61 Stayci Taylor Dogsbody: An Overview of Transmorphic Techniques as Humour Devices and their Impact in Alberto Montt’s Cartoons 79 Beatriz Carbajal Carrera Bakhtin and Borat: The Rogue, the Clown, and the Fool in Carnival Film 105 E. -

The Shape of Women: Corsets, Crinolines & Bustles

The Shape of Women: Corsets, Crinolines & Bustles – c. 1790-1900 1790-1809 – Neoclassicism In the late 18th century, the latest fashions were influenced by the Rococo and Neo-classical tastes of the French royal courts. Elaborate striped silk gowns gave way to plain white ones made from printed cotton, calico or muslin. The dresses were typically high-waisted (empire line) narrow tubular shifts, unboned and unfitted, but their minimalist style and tight silhouette would have made them extremely unforgiving! Underneath these dresses, the wearer would have worn a cotton shift, under-slip and half-stays (similar to a corset) stiffened with strips of whalebone to support the bust, but it would have been impossible for them to have worn the multiple layers of foundation garments that they had done previously. (Left) Fashion plate showing the neoclassical style of dresses popular in the late 18th century (Right) a similar style ball- gown in the museum’s collections, reputedly worn at the Duchess of Richmond’s ball (1815) There was public outcry about these “naked fashions,” but by modern standards, the quantity of underclothes worn was far from alarming. What was so shocking to the Regency sense of prudery was the novelty of a dress made of such transparent material as to allow a “liberal revelation of the human shape” compared to what had gone before, when the aim had been to conceal the figure. Women adopted split-leg drawers, which had previously been the preserve of men, and subsequently pantalettes (pantaloons), where the lower section of the leg was intended to be seen, which was deemed even more shocking! On a practical note, wearing a short sleeved thin muslin shift dress in the cold British climate would have been far from ideal, which gave way to a growing trend for wearing stoles, capes and pelisses to provide additional warmth. -

Urban Representation in Fashion Magazines

Chair of Urban Studies and Social Research Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism Bauhaus-University Weimar Fashion in the City and The City in Fashion: Urban Representation in Fashion Magazines Doctoral dissertation presented in fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor philosophiae (Dr. phil.) Maria Skivko 10.03.1986 Supervising committee: First Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Frank Eckardt, Bauhaus-University, Weimar Second Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Stephan Sonnenburg, Karlshochschule International University, Karlsruhe Thesis Defence: 22.01.2018 Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. 5 Thesis Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 6 Part I. Conceptual Approach for Studying Fashion and City: Theoretical Framework ........................ 16 Chapter 1. Fashion in the city ................................................................................................................ 16 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 16 1.1. Fashion concepts in the perspective ........................................................................................... 18 1.1.1. Imitation and differentiation ................................................................................................ 18 1.1.2. Identity -

The War and Fashion

F a s h i o n , S o c i e t y , a n d t h e First World War i ii Fashion, Society, and the First World War International Perspectives E d i t e d b y M a u d e B a s s - K r u e g e r , H a y l e y E d w a r d s - D u j a r d i n , a n d S o p h i e K u r k d j i a n iii BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA 29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2021 Selection, editorial matter, Introduction © Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian, 2021 Individual chapters © their Authors, 2021 Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Editors of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgments on p. xiii constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design by Adriana Brioso Cover image: Two women wearing a Poiret military coat, c.1915. Postcard from authors’ personal collection. This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third- party websites referred to or in this book.