Echoes of the Master: a Multi-Dimensional Mapping of Enrique Granados’ Pedagogical Method and Pianistic Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selected Intermediate-Level Solo Piano Music Of

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Selected intermediate-level solo piano music of Enrique Granados: a pedagogical analysis Harumi Kurihara Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Kurihara, Harumi, "Selected intermediate-level solo piano music of Enrique Granados: a pedagogical analysis" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3242. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3242 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SELECTED INTERMEDIATE-LEVEL SOLO PIANO MUSIC OF ENRIQUE GRANADOS: A PEDAGOGICAL ANALYSIS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Harumi Kurihara B.M., Loyola University, New Orleans, 1993 M.M.,University of New Orleans, 1997 August, 2005 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere appreciation to my major professor, Professor Victoria Johnson for her expert advice, patience, and commitment to my monograph. Without her help, I would not have been able to complete this monograph. I am also grateful to my committee members, Professors Jennifer Hayghe, Michael Gurt, and Jeffrey Perry for their interest and professional guidance in making this monograph possible. I must also recognize the continued encouragement and support of Professor Constance Carroll who provided me with exceptional piano instruction throughout my doctoral studies. -

An Investigation of the Sonata-Form Movements for Piano by Joaquín Turina (1882-1949)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository CONTEXT AND ANALYSIS: AN INVESTIGATION OF THE SONATA-FORM MOVEMENTS FOR PIANO BY JOAQUÍN TURINA (1882-1949) by MARTIN SCOTT SANDERS-HEWETT A dissertatioN submitted to The UNiversity of BirmiNgham for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC DepartmeNt of Music College of Arts aNd Law The UNiversity of BirmiNgham September 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT Composed between 1909 and 1946, Joaquín Turina’s five piano sonatas, Sonata romántica, Op. 3, Sanlúcar de Barrameda, Op. 24, Sonata Fantasía, Op. 59, Concierto sin Orquesta, Op. 88 and Rincón mágico, Op. 97, combiNe established formal structures with folk-iNspired themes and elemeNts of FreNch ImpressioNism; each work incorporates a sonata-form movemeNt. TuriNa’s compositioNal techNique was iNspired by his traiNiNg iN Paris uNder ViNceNt d’Indy. The unifying effect of cyclic form, advocated by d’Indy, permeates his piano soNatas, but, combiNed with a typically NoN-developmeNtal approach to musical syNtax, also produces a mosaic-like effect iN the musical flow. -

1 Fons Sants Sagrera I Anglada Partitures I Documentació De Sants

Fons Sants Sagrera i Anglada Partitures i documentació de Sants Sagrera i Anglada Secció de Música Biblioteca de Catalunya 2019 SUMARI Identificació Context Contingut i estructura Condicions d’accés i ús Documentació relacionada Notes Control de la descripció Inventari IDENTIFICACIÓ Codi de referència: BC, Fons Sants Sagrera i Anglada Nivell de descripció: Fons Títol: Partitures i documentació de Sants Sagrera i Anglada Dates de creació: 1880-1980 Dates d’agregació: 1911-2005 Volum i suport de la unitat de descripció: 1,34 metres lineals (11 capses, 3.251 documents aproximadament): Documentació: - 17 àlbums (2252 unitats documentals aproximadament) - Col·leccions (391 programes, 19 publicacions periòdiques, 19 retalls de premsa, 6 fotografies, 9 caricatures i dibuixos, 3 nadales, 1 postal) - Documentació professional (6 unitats documentals) - Correspondència (2 unitats documentals) - Documentació vària (23 unitats documentals) Partitures: - 520 unitats documentals aproximadament CONTEXT Nom del productor: Sants Sagrera i Anglada Notícia biogràfica: Sants Sagrera i Anglada (Girona, 1893 - Barcelona, 2 de gener de 1983). Violoncel·lista i pedagog. Començà els seus estudis musicals a l’Acadèmia d’Isidre i Tomàs Mollera a Girona. Posteriorment continuà els estudis de violoncel a l’Escola Municipal de Barcelona amb Josep Soler i Ventura. Més tard amplià la seva formació com a violoncel·lista amb Gaspar Cassadó i de música de cambra amb Joan Massià i Prats. 1 Principalment es dedicà a la interpretació d’obres de música de cambra, sent fundador junt amb altres músics de diferents formacions musicals, d’entre les quals cal remarcar les següents: el Quintet Català de Girona (ca. 1912), format per Josep Dalmau, Rafael Serra (violinistes), Josep Serra (violista), Sants Sagrera i Tomàs Mollera (pianista); el Trio Girona (ca. -

La Academia Granados-Marshall Y Su Contribución a La Consolidación De La Técnico-Pedagogía Española: Actividad Y Rendimiento Entre 1945 Y 19551

LA ACADEMIA GRANADOS-MARSHALL Y SU CONTRIBUCIÓN A LA CONSOLIDACIÓN DE LA TÉCNICO-PEDAGOGÍA ESPAÑOLA: ACTIVIDAD Y RENDIMIENTO ENTRE 1945 Y 19551. Por Aida Velert Hernández 1 La información que ofrezco en este artículo procede del Trabajo Fin de Grado Superior en la Especialidad de Piano inédito que realicé bajo la dirección de la dra. Victoria Alemany y presenté al Departamento de Instrumentos Polifónicos del Conservatorio Superior de Música “Joaquín Rodrigo” de Valencia en 2013 [Velert (2013)]. Descubrí la Academia Marshall el curso 2003-2004, cuando iba a cumplir catorce años y fui aceptada como alumna en dicho centro sin ser en absoluto consciente al principio de su prestigio, y poco a poco me fue fascinando lentamente. Una entidad que ha sido capaz de mantenerse firme e imperturbable durante más de una centuria, que ha sido testigo directo de los cambios/transformaciones sociopolíticas2 y económicas del país resistiendo embistes y contratiempos, y que ha logrado formar a algunos de los pianistas más relevantes del siglo XX en España, estimo que merece ser estudiada en profundidad. En definitiva, decidí abordar la investigación sobre un período de la existencia de esta academia en mi Trabajo Fin de Grado Superior por el respeto y la admiración que siento hacia esta institución, que se han ido acrecentando con el paso del tiempo. Facilitó mi tarea contar con abundante información aportada gentilmente por el Centro Documental de la Academia Marshall (CEDAM), por lo que quiero en primer lugar agradecer sinceramente al personal de administración de la Academia, y en especial a su directora de gestión doña Cintia Matamoros3, su confianza y la inestimable ayuda que me han brindado de forma desinteresada en todo momento. -

ENRIQUE GRANADOS INÉDITO ( En Recuerdo De Antonio Fernández Cid)

CICLO ENRIQUE GRANADOS INÉDITO ( En recuerdo de Antonio Fernández Cid) FEBRERO-MARZO 1996 Fundación Juan March CICLO ENRIQUE GRANADOS INÉDITO (En recuerdo de Antonio Fernández Cid) FEBRERO-MARZO 1996 ÍNDICE Pág. Presentación 3 Semblanza de Enrique Granados, por Antonio Fernández-Cid 5 Programa general 9 Notas al programa, por Douglas Riva 13 La obra pianística de Granados 13 Primer concierto 16 Segundo concierto 19 Intérprete 23 Hace cinco años, con motivo del 75 aniversario de la muerte de Enrique Granados, organizamos un ciclo de tres conciertos sobre su obra pianística. Aunque entonces oímos toda su obra editada, éramos conscientes de que faltaban algunas obras inéditas o poco conocidas que ahora vamos a ofrecer en este nuevo ciclo para completar el panorama entonces trazado. La inclusión ahora de algunas obras famosas que entonces oímos no es sólo para dotar de alguna perspectiva a las piezas inéditas. Es bien sabido que Granados era un improvisador nato y que las presiones de los editores le "obligaron " a dar a la estampa obras sobre las que aún tenía cosas que decir. En algunos casos, las escribió, y ahora se podrán escuchar en una versión ligeramente distinta a la habitual. En todos los demás, las versiones que ofrece Douglas Riva son el resultado de un concienzudo análisis de los manuscritos originales, cuya consecuencia es el haber limpiado de errores y erratas las ediciones que normalmente se utilizan. Hasta que publique la edición en la que viene trabajando desde hace tiempo, son también, a su modo, versiones inéditas. En el ciclo que hicimos en noviembre de 1991, las notas al programa y la presentación general corrieron a cargo de Antonio Fernández-Cid, de cuya muerte en plena actividad se cumple ahora un año. -

Iberia De Isaac Albéniz: Estudio De Sus Interpretaciones a Través De “El Puerto” En Los Registros Sonoros

Tesis doctoral Iberia de Isaac Albéniz: Estudio de sus interpretaciones a través de “El Puerto” en los registros sonoros por María de Lourdes Rebollo García Director: Dr. Francesc Cortès i Mir Programa de Doctorado en Historia del Arte y Musicología Departament d'Art i de Musicologia Facultat de Filosofia i Llletres Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Mayo 2015 Tesis doctoral Iberia de Isaac Albéniz: Estudio de sus interpretaciones a través de “El Puerto” en los registros sonoros Autora: María de Lourdes Rebollo García Director: Dr. Francesc Cortès i Mir Programa de Doctorado en Historia del Arte y Musicología Departament d'Art i de Musicologia Facultat de Filosofia i Llletres Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Mayo 2015 A Adrián y Ana Victoria, mis tesoros 4 AGRADECIMIENTOS En primer lugar quiero expresar mi más sincero agradecimiento al doctor Francesc Cortès i Mir por aceptar ser el director de esta tesis, por orientarme en la investigación, y por sus observaciones y correcciones puntuales a este texto. Pero sobre todo, por sus valiosos consejos y sugerencias siempre de manera cordial y abierta que me motivaron a llevar a buen fin esta investigación. Agradezco al doctor Joaquim Rabaseda i Matas su orientación y asesoría al inicio de este trabajo, y a la doctora Montserrat Claveria su apoyo en la tramitación de mi ingreso al doctorado. La realización de mis estudios de doctorado en la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona fue posible gracias al apoyo de una beca concedida por el Programa de Becas para Estudios en el Extranjero del Fondo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes (FONCA) en México. -

Homenaje De Enrique Granados Al Cant D'estil: Danza Nº 7 «Valenciana»

Homenaje de Enrique Granados al cant d’estil: Danza Nº 7 «Valenciana» MARÍA ORDIÑANA GIL Universidad Internacional de Valencia Resumen Enrique Granados ha sido considerado un icono español, un referente de la primera generación modernista surgida a partir de la segunda mitad del siglo XIX. La valorización positiva del folclore y de la historia de la música, así como su voluntad de internacionalización se muestran en la primera de sus obras maestras: Danzas españolas. A través de la Danza nº 7 «Valenciana» el presente artículo se propone ahondar en el conocimiento de Granados soBre la música popular tradicional valenciana y el tratamiento de sus melodías y rasgos distintivos. Asimismo, se pretende dilucidar los vínculos –profesionales y personales– que el compositor tuvo con Valencia a partir de las relaciones con la familia Gal-Lloveras y con el crítico, periodista y compositor Eduardo López-Chavarri Marco. Palabras claves: Enrique Granados, danzas españolas, folclore, Valencia, modernismo, nacionalismo Abstract Enrique Granados is considered a Spanish icon, a member of the first modernist generation that emerged from the second half of the nineteenth century. Granados's valorization of folklore and music history, as well as his determination to gain international recognition for his music are evident in the first of his masterpieces: the Danzas españolas. Using Danza nº 7 «Valenciana» as the prime example, this article aims to show what Granados knew about traditional Valencian popular music and how he treated its distinctive melodies and features. Likewise, it will elucidate the Bond –professional and personal– that the composer had with Valencia through his relations with the Gal-Lloveras family and the critic- journalist-composer Eduardo López-Chavarri Marco. -

V0. the PEDAGOGICAL METHODS of ENRIQUE GRANADOS and FRANK MARSHALL

£7? A/dU /v0. THE PEDAGOGICAL METHODS OF ENRIQUE GRANADOS AND FRANK MARSHALL: AN ILLUMINATION OF RELEVANCE TO PERFORMANCE PRACTICE AND INTERPRETATION IN GRANADOS' ESCENAS ROMANTICAS. A LECTURE RECITAL TOGETHER WITH THREE RECITALS OF SELECTED WORKS OF SCHUBERT, PROKOFIEFF, CHOPIN, POULENC, AND RACHMANINOFF DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By Mark R. Hansen, B.M., M.M. Denton, Texas December, 1988 Hansen, Mark R., The Pedagogical Methods of Enrique Granados and Frank Marshall: An Illumination of Relevance to Performance Practice and Interpretation in Granados' Escenas Romanticas, A Lecture Recital together with Three Recitals of Selected Works of Schubert. Prokofieff. Chooin. Poulenc, and Rachmaninoff. Doctor of Musical Arts (Piano Performance), December, 1988, 55 pp., 53 examples, bibliography, 28 titles. Enrique Granados, Frank Marshall, and Alicia de Larrocha are the chief exponents of a school of piano playing characterized by special attention to details of pedalling, voicing, and refined piano sonority. Granados and Marshall dedicated the major part of their efforts in the field to the pedagogy of these principles. Their work led to the establishment of the Granados Academy in Barcelona, a keyboard conservatory which operates today under the name of the Frank Marshall Academy. Both Granados and Marshall have left published method books detailing their pedagogy of pedalling and tone production. Granados' book, Metodo Teorico Practico para el Uso de los Pedales del Piano (Theoretical and Practical Method for the Use of the Piano Pedals) is presently out of print and available in a photostatic version from the publisher. -

Music Programme :Music

DM İSTANBUL TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES A STUDY ON THE AUTHENTICITY AND EVOLUTION OF PIANO TECHNIQUE FOR SPANISH PIANO MUSIC: WITH SELECTIONS FROM THE REPERTOIRE OF ALBÉNIZ, GRANADOS AND FALLA IF NECESSARY THIRDLINE Ph.D. Thesis by Beray SELEN Department :Music Programme :Music JUNE 2009 i ii FOREWORD This doctorate thesis, titled " A Study On The Authenticity and Evolution of Piano Technique for Spanish Piano Music: With Selections From the Repertoire of Albéniz, Granados and Falla," was prepared at the I.T.U. Social Sciences Institute, Dr. Erol Uçer Center for Advanced Studies in Music (MIAM). This thesis presents results from my concern on the specifics of performance issues regarding Spanish Piano repertoire as well as my lifelong aim in trying to find a synthesis between factors outside of piano performance. These factors come from the core of the music and the culture it is born out of, and may be used in a way to help improve the performance aspect. My personal interest in the difficult and rhythmically complex nature of Spanish music gave rise to a further elaboration of this ideal through the Spanish piano repertoire of Albéniz, Granados and Falla. Coinciding with the writing process of this thesis, I had the chance to discover more useful aspects of music that are beyond just technical aspects of keyboard playing. In retrospect, this study allowed me to arrive at a further instrumental “overarching” angle to help and guide people interested in Spanish Piano repertoire. The project aims at investigating whether it is possible to see aspects of the Spanish piano music from diverse perspectives. -

Complete Guitar Music

Asencio COMPLETE GUITAR MUSIC ALBERTO MESIRCA GUITAR Vicente Asencio 1908-1979 Vicente Asencio is one of those 20th century composers whose works for the guitar Complete Guitar Music met with widespread acclaim, although he didn’t actually play the instrument himself. Indeed, he was essentially an excellent pianist who had studied at the Collectici Íntim (1965) Suite Valenciana (1970) Marshall Academy in Barcelona, where the influence of the great Enrique Granados 1. La Serenor 4’22 10. Preludi 2’05 was still tangible. As a composer, he deliberately and passionately chose to adhere 2. La Joia 2’41 11. Cançoneta 4’33 to the musical tradition of his native Valencia, which might appear to be a cultural 3. La Calma 2’56 12. Dansa 2’42 limitation, given the nature of the events that marked musical life during the first 4. La Gaubança 1’54 half of the 1900s. Far from being provincial, however, Asencio was an artist of 5. La Frisança 2’54 13. Danza Valenciana (1963) 4’00 considerable learning who was open-minded, unprejudiced and interested in all aspects of new music. In 1934, along with other Valencian musicians, he founded the 6. Cançó d’hivern (1935) 4’31 Suite Mistica (1971) Grupo de los Jovenes, declaring that «We aim to achieve a form of Valencian music 14. Getsémani 3’06 that is vigorous and rich, to promote a Valencian school that is fruitful and varied, Suite de Homenajes (1950) 15. Dipsô 8’06 that incorporates in universal music the psychological traits and emotions of our 7. -

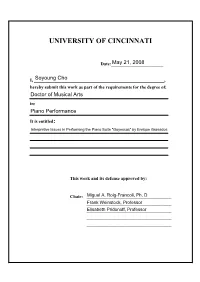

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________May 21, 2008 I, _________________________________________________________,Soyoung Cho hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in: Piano Performance It is entitled: Interpretive Issues in Performing the Piano Suite "Goyescas" by Enrique Granados This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________Miguel A. Roig-Francoli, Ph. D _______________________________Frank Weinstock, Professor _______________________________Elisabeth Pridonoff, Professor _______________________________ _______________________________ Interpretive Issues in Performing the Piano Suite “Goyescas” by Enrique Granados A doctoral document submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Division of Keyboard Studies of the College-Conservatory of Music 2008 by Soyoung Cho M. M., Ewha Womans University, 1997 B. M., Kyung-Won University, 1992 Committee Chair: Miguel A. Roig-Francoli, Ph.D. Abstract Goyescas is a very challenging work full of Granados’s artistic devotion for searching the authentic Spanish character in a variety of ways. Numerous Spanish elements – references to Goya’s works, tonadillas, Spanish dances and songs, sound of guitars and castanets, etc. – are incorporated into this work. It is, indeed, a complex art work that interrelates visual arts, poetry, and music, all with a Spanish subject. Any pianists planning to study Granados’s Goyescas should first acquire the necessary background based on a thorough study of the music and its history. Knowledge of Granados’s inspiration from Goya’s works, the piece’s narrative elements related with the opera Goyescas, Spanish idioms, and the improvisatory nature of Granados’s piano style, is indispensable for fully understanding, interpreting, and performing this work. -

Piano Douglas Riva, Piano Michele Scanlon, Piano Mark Kruczek, Organ

Voices of Ascension Dennis Keene Artistic Director & Conductor Thursday, February 9, 2017 at 8:00pm The Church of the Ascension Fifth Avenue and Tenth Street New York City Performance in honor of Roberta Huber Spain: Granados, Falla & Modernisme Vanessa Vasquez, soprano Francesca dePasquale, violin Vanessa Perez, piano Douglas Riva, piano Michele Scanlon, piano Mark Kruczek, organ Silver Jubilee Society Concert Sponsor Jeffrey & Valerie Paley Piano by Steinway & Sons The audience is urged at this time to make sure that all cell phones and other electronic devices are turned off. The use of cameras and recording devices is strictly prohibited. Members of the audience are cordially invited to greet the artists at a reception following the concert in the Parish Hall (enter through the right side doors). Program ROSARIUM BEATAE VIRGINIS MARIAE PABLO CASALS 1876-1973 Voices of Ascension, Dennis Keene, Conductor, Elena Williamson, soprano, and Mark Kruczek, organ Pau (Pablo) Casals was born in El Vendrell (near Barcelona) in 1876 and died in San Juan, Puerto Rico in 1973. Casals was celebrated throughout the world as cellist, conductor and as a fighter for human rights. He was also a composer of a small body of very beautiful music. These choral works were composed for the men and boy choir of the monastery in Montserrat, Spain. Each piece reveals his ability to express spiritual feelings in a simple, genuine and personal manner. TheRosaries was intended to be sung in the services at Montserrat. The work is a series of very short movements, and is inspired by the tradition of congregational sections alternating with sections for chapel choir or soloists.