University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selected Intermediate-Level Solo Piano Music Of

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Selected intermediate-level solo piano music of Enrique Granados: a pedagogical analysis Harumi Kurihara Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Kurihara, Harumi, "Selected intermediate-level solo piano music of Enrique Granados: a pedagogical analysis" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3242. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3242 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SELECTED INTERMEDIATE-LEVEL SOLO PIANO MUSIC OF ENRIQUE GRANADOS: A PEDAGOGICAL ANALYSIS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Harumi Kurihara B.M., Loyola University, New Orleans, 1993 M.M.,University of New Orleans, 1997 August, 2005 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere appreciation to my major professor, Professor Victoria Johnson for her expert advice, patience, and commitment to my monograph. Without her help, I would not have been able to complete this monograph. I am also grateful to my committee members, Professors Jennifer Hayghe, Michael Gurt, and Jeffrey Perry for their interest and professional guidance in making this monograph possible. I must also recognize the continued encouragement and support of Professor Constance Carroll who provided me with exceptional piano instruction throughout my doctoral studies. -

¿Granados No Es Un Gran Maestro? Análisis Del Discurso Historiográfico Sobre El Compositor Y El Canon Nacionalista Español

¿Granados no es un gran maestro? Análisis del discurso historiográfico sobre el compositor y el canon nacionalista español MIRIAM PERANDONES Universidad de Oviedo Resumen Enrique Granados (1867-1916) es uno de los tres compositores que conforman el canon del Nacionalismo español junto a Manuel de Falla (1876- 1946) e Isaac Albéniz (1860-1909) y, sin embargo, este músico suele quedar a la sombra de sus compatriotas en los discursos históricos. Además, Granados también está fuera del “trío fundacional” del Nacionalismo formado por Felip Pedrell (1841-1922) —considerado el maestro de los tres compositores nacionalistas, y, en consecuencia, el “padre” del nacionalismo español—Albéniz y Falla. En consecuencia, uno de los objetivos de este trabajo es discernir por qué Granados aparece en un lugar secundario en la historiografía española, y cómo y en base a qué premisas se conformó este canon musical. Palabras clave: Enrique Granados, canon, Nacionalismo, historiografia musical. Abstract Enrique Granados (1867-1916) is one of the three composers Who comprise the canon of Spanish nationalism, along With Manuel de Falla (1876-1946) and Isaac Albéniz (1860-1909). HoWeVer, in the realm of historical discourse, Granados has remained in the shadoW of his compatriots. MoreoVer, Granados lies outside the “foundational trio” of nationalism, formed by Felip Pedrell (1841-1922)— considered the teacher of the three nationalist composer and, as a consequence, the “father” of Spanish nationalism—Albéniz y Falla. Therefore, one of the objectiVes of this study is to discern why Granados occupies a secondary position in Spanish historiography, and most importantly, for What reasons the musical canon eVolVed as it did. -

An Investigation of the Sonata-Form Movements for Piano by Joaquín Turina (1882-1949)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository CONTEXT AND ANALYSIS: AN INVESTIGATION OF THE SONATA-FORM MOVEMENTS FOR PIANO BY JOAQUÍN TURINA (1882-1949) by MARTIN SCOTT SANDERS-HEWETT A dissertatioN submitted to The UNiversity of BirmiNgham for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC DepartmeNt of Music College of Arts aNd Law The UNiversity of BirmiNgham September 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT Composed between 1909 and 1946, Joaquín Turina’s five piano sonatas, Sonata romántica, Op. 3, Sanlúcar de Barrameda, Op. 24, Sonata Fantasía, Op. 59, Concierto sin Orquesta, Op. 88 and Rincón mágico, Op. 97, combiNe established formal structures with folk-iNspired themes and elemeNts of FreNch ImpressioNism; each work incorporates a sonata-form movemeNt. TuriNa’s compositioNal techNique was iNspired by his traiNiNg iN Paris uNder ViNceNt d’Indy. The unifying effect of cyclic form, advocated by d’Indy, permeates his piano soNatas, but, combiNed with a typically NoN-developmeNtal approach to musical syNtax, also produces a mosaic-like effect iN the musical flow. -

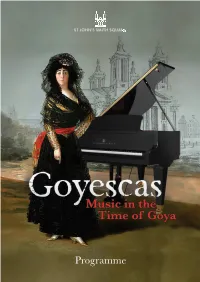

Music in the Time of Goya

Music in the Time of Goya Programme ‘Goyescas’: Music in the Time of Goya Some of the greatest names in classical music support the Iberian and Latin American Music Society with their membership 2 November 2016, 7.00pm José Menor piano Daniel Barenboim The Latin Classical Chamber Orchestra featuring: Argentine pianist, conductor Helen Glaisher-Hernández piano | Elena Jáuregui violin | Evva Mizerska cello Nicole Crespo O’Donoghue violin | Cressida Wislocki viola and ILAMS member with special guest soloists: Nina Corti choreography & castanets Laura Snowden guitar | Christin Wismann soprano Opening address by Jordi Granados This evening the Iberian and Latin American Music Society (ILAMS) pays tribute to one of Spain’s most iconic composers, Enrique Granados (1867–1916) on the centenary year of his death, with a concert programme inspired by Granados’ greatest muse, the great Spanish painter Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828), staged amidst the Baroque splendour of St John’s Smith Square – a venue which, appropriately, was completed not long before Goya’s birth, in 1728. Enrique Granados To pay homage to Granados here in London also seems especially fi tting given that the great Composer spent his fi nal days on British shores. Granados Will you drowned tragically in the English Channel along with his wife Amparo after their boat, the SS Sussex, was torpedoed by the Germans. At the height of his join them? compositional powers, Granados had been en route to Spain from New York where his opera, Goyescas, had just received its world premiere, and where he had also given a recital for President Woodrow Wilson; in his lifetime Granados was known as much for his virtuoso piano playing as for his talent as a composer. -

Granados: Goyescas

Goyescas Enrique Granados 1. Los Requiebros [9.23] 2. Coloquio en La Reja [10.53] 3. El Fandango de Candil [6.41] 4. Quejas, ó la Maja y el Ruiseñor [6.22] 5. El Amor y la Muerte: Balada [12.43] 6. Epilogo: Serenata del Espectro [7.39] Total Timings [54.00] Ana-Maria Vera piano www.signumrecords.com The Goyescas suite has accompanied me throughout with her during the recording sessions and felt G my life, and I always knew that one day I would generous and grounded like never before. The music attempt to master it.The rich textures and came more easily as my perspectives broadened aspiring harmonies, the unfurling passion and I cared less about perfection. Ironically this is tempered by restraint and unforgiving rhythmic when you stand the best chance of approaching precision, the melancholy offset by ominous, dark your ideals and embracing your audience. humour, the elegance and high drama, the resignation and the hopefulness all speak to my sense of © Ana-Maria Vera, 2008 being a vehicle, offeeling the temperature changes, the ambiguity, and the emotion the way an actor might live the role of a lifetime. And so this particular project has meant more to me than almost any in my career. Catapulted into the limelight as a small child, I performed around the globe for years before realising I had never had a chance to choose a profession for myself. Early success, rather than going to my head, affected my self-confidence as a young adult and I began shying away from interested parties, feeling the attention wasn't deserved and therefore that it must be of the wrong kind. -

Sounding Nostalgia in Post-World War I Paris

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Tristan Paré-Morin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Paré-Morin, Tristan, "Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3399. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Abstract In the years that immediately followed the Armistice of November 11, 1918, Paris was at a turning point in its history: the aftermath of the Great War overlapped with the early stages of what is commonly perceived as a decade of rejuvenation. This transitional period was marked by tension between the preservation (and reconstruction) of a certain prewar heritage and the negation of that heritage through a series of social and cultural innovations. In this dissertation, I examine the intricate role that nostalgia played across various conflicting experiences of sound and music in the cultural institutions and popular media of the city of Paris during that transition to peace, around 1919-1920. I show how artists understood nostalgia as an affective concept and how they employed it as a creative resource that served multiple personal, social, cultural, and national functions. Rather than using the term “nostalgia” as a mere diagnosis of temporal longing, I revert to the capricious definitions of the early twentieth century in order to propose a notion of nostalgia as a set of interconnected forms of longing. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: NATIONAL

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: NATIONAL CHARACTER AS EXPRESSED IN PIANO LITERATURE Yong Sook Park, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2005 Dissertation directed by: Bradford Gowen, Professor of Music In the middle of the 19th century, many composers living outside of mainstream musical countries such as Germany and France attempted to establish their own musical identity. A typical way of distinguishing themselves from German, French, and Italian composers was to employ the use of folk elements from their native lands. This resulted in a vast amount of piano literature that was rich in national idioms derived from folk traditions. The repertoire reflected many different national styles and trends. Due to the many beautiful, brilliant, virtuosic, and profound ideas that composers infused into these nationalistic works, they took their rightful place in the standard piano repertoire. Depending on the compositional background or style of the individual composers, folk elements were presented in a wide variety of ways. For example, Bartók recorded many short examples collected from the Hungarian countryside and used these melodies to influence his compositional style. Many composers enhanced and expanded piano technique. Liszt, in his Hungarian Rhapsodies, emphasized rhythmic vitality and virtuosic technique in extracting the essence of Hungarian folk themes. Chopin and Szymanowski also made use of rhythmic figurations in their polonaises and mazurkas, often making use of double-dotted rhythms. Obviously, composers made use of nationalistic elements to add to the piano literature and to expand the technique of the piano. This dissertation comprises three piano recitals presenting works of: Isaac Albeniz, Bela Bartók, Frédéric Chopin, Enrique Granados, Edvard Grieg, Franz Liszt, Frederic Rzewski, Alexander Scriabin, Karol Szymanowski, and Peter Ilich Tchaikovsky. -

1 Fons Sants Sagrera I Anglada Partitures I Documentació De Sants

Fons Sants Sagrera i Anglada Partitures i documentació de Sants Sagrera i Anglada Secció de Música Biblioteca de Catalunya 2019 SUMARI Identificació Context Contingut i estructura Condicions d’accés i ús Documentació relacionada Notes Control de la descripció Inventari IDENTIFICACIÓ Codi de referència: BC, Fons Sants Sagrera i Anglada Nivell de descripció: Fons Títol: Partitures i documentació de Sants Sagrera i Anglada Dates de creació: 1880-1980 Dates d’agregació: 1911-2005 Volum i suport de la unitat de descripció: 1,34 metres lineals (11 capses, 3.251 documents aproximadament): Documentació: - 17 àlbums (2252 unitats documentals aproximadament) - Col·leccions (391 programes, 19 publicacions periòdiques, 19 retalls de premsa, 6 fotografies, 9 caricatures i dibuixos, 3 nadales, 1 postal) - Documentació professional (6 unitats documentals) - Correspondència (2 unitats documentals) - Documentació vària (23 unitats documentals) Partitures: - 520 unitats documentals aproximadament CONTEXT Nom del productor: Sants Sagrera i Anglada Notícia biogràfica: Sants Sagrera i Anglada (Girona, 1893 - Barcelona, 2 de gener de 1983). Violoncel·lista i pedagog. Començà els seus estudis musicals a l’Acadèmia d’Isidre i Tomàs Mollera a Girona. Posteriorment continuà els estudis de violoncel a l’Escola Municipal de Barcelona amb Josep Soler i Ventura. Més tard amplià la seva formació com a violoncel·lista amb Gaspar Cassadó i de música de cambra amb Joan Massià i Prats. 1 Principalment es dedicà a la interpretació d’obres de música de cambra, sent fundador junt amb altres músics de diferents formacions musicals, d’entre les quals cal remarcar les següents: el Quintet Català de Girona (ca. 1912), format per Josep Dalmau, Rafael Serra (violinistes), Josep Serra (violista), Sants Sagrera i Tomàs Mollera (pianista); el Trio Girona (ca. -

Repertoire Report 2012-13 Season Group 7 & 8 Orchestras

REPERTOIRE REPORT 2012-13 SEASON GROUP 7 & 8 ORCHESTRAS Composer Work First Perf. Conductor Orchestra Soloist(s) Actor, Lee DIVERTIMENTO FOR SMALL ORCHESTRA Apr. 27, 2013 Emily Ray Mission Chamber Orchestra Adams, John SHORT RIDE IN A FAST MACHINE Oct. 13, 2012 Fouad Fakhouri Fayetteville Symphony Orchestra Bach, J. S. TOCCATA AND FUGUE, BWV 565, D MINOR Oct. 27, 2012 Charles Latshaw Bloomington Symphony (STOWKOWSKI) (STOWKOWSKI,) Orchestra Barber, Samuel CONCERTO, VIOLIN AND ORCHESTRA, Feb. 2, 2013 Jason Love The Columbia Orchestra Madeline Adkins, violin OPUS 14 Barber, Samuel OVERTURE TO THE SCHOOL FOR Feb. 9, 2013 Herschel Kreloff Civic Orchestra of Tucson SCANDAL Bartok, Béla ROMANIAN FOLK DANCES Sep. 29, 2012 Steven Lipsitt Boston Classical Orchestra Beethoven, Ludwig V. CONCERTO, PIANO, NO. 5 IN E-FLAT Apr. 14, 2013 Joel Lazar Symphony of the Potomac Sayaka Jordan, piano MAJOR, OP. 73 Beethoven, Ludwig V. CONCERTO, VIOLIN, IN D MAJOR, OPUS Nov. 17, 2012 Steven Lipsitt Boston Classical Orchestra Sharon Roffman, violin 61 Beethoven, Ludwig V. CORIOLAN: OVERTURE, OPUS 62 Mar. 9, 2013 Fouad Fakhouri Fayetteville Symphony Orchestra Apr. 14, 2013 Joel Lazar Symphony of the Potomac Beethoven, Ludwig V. EGMONT: OVERTURE, OPUS 84 Oct. 20, 2012 Steven Lipsitt Boston Classical Orchestra Beethoven, Ludwig V. SONATA FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO, Apr. 13, 2013 Steven Lipsitt Boston Classical Orchestra "SPRING" III RONDO Beethoven, Ludwig V. SYMPHONY NO. 1 IN C MAJOR, OPUS 21 Apr. 27, 2013 Emily Ray Mission Chamber Orchestra Beethoven, Ludwig V. SYMPHONY NO. 3 IN E-FLAT MAJOR, Apr. 14, 2013 Joel Lazar Symphony of the Potomac OPUS 55 Page 1 of 13 REPERTOIRE REPORT 2012-13 SEASON GROUP 7 & 8 ORCHESTRAS Composer Work First Perf. -

María Del Carmen Opera in Three Acts

Enrique GRANADOS María del Carmen Opera in Three Acts Veronese • Suaste Alcalá • Montresor Wexford Festival Opera Chorus National Philharmonic Orchestra of Belarus Max Bragado-Darman CD 1 43:33 5 Yo también güervo enseguía Enrique (Fuensanta, María del Carmen) 0:36 Act 1 6 ¡Muy contenta! y aquí me traen, como aquel GRANADOS 1 Preludio (Orchestra, Chorus) 6:33 que llevan al suplicio (María del Carmen) 3:46 (1867-1916) 2 A la paz de Dios, caballeros (Andrés, Roque) 1:28 7 ¡María del Carmen! (Pencho, María del Carmen) 5:05 3 Adiós, hombres (Antón, Roque) 2:27 8 ¿Y qué quiere este hombre a quien maldigo María del Carmen 4 ¡Mardita sea la simiente que da la pillería! desde el fondo de mi alma? (Pepuso, Antón) 1:45 (Javier, Pencho, María del Carmen) 4:10 Opera in Three Acts 9 5 ¿Pos qué es eso, tío Pepuso? ¡Ah!, tío Pepuso, lléveselo usted (Roque, Pepuso, Young Men) 3:04 (María del Carmen, Pepuso, Javier, Pencho) 0:32 Libretto by José Feliu Codina (1845-1897) after his play of the same title 0 6 ¡Jesús, la que nos aguarda! Ya se fue. Alégrate corazón mío Critical Edition: Max Bragado-Darman (Don Fulgencio, Pepuso, Roque) 1:49 (María del Carmen, Javier) 0:55 ! ¡Viva María el Carmen y su enamorao, Javier! Published by Ediciones Iberautor/Instituto Complutense de Ciencias Musicales 7 Una limosna para una misa de salud… (Canción de la Zagalica) (María del Carmen, (Chorus, Domingo) 5:22 @ ¡Pencho! ¡Pencho! (Chorus) ... Vengo a delatarme María del Carmen . Diana Veronese, Soprano Fuensanta, Don Fulgencio, Pepuso, Roque) 6:59 8 Voy a ver a mi enfermo, el capellán para salvar a esta mujer (Pencho, Domingo, Concepción . -

La Academia Granados-Marshall Y Su Contribución a La Consolidación De La Técnico-Pedagogía Española: Actividad Y Rendimiento Entre 1945 Y 19551

LA ACADEMIA GRANADOS-MARSHALL Y SU CONTRIBUCIÓN A LA CONSOLIDACIÓN DE LA TÉCNICO-PEDAGOGÍA ESPAÑOLA: ACTIVIDAD Y RENDIMIENTO ENTRE 1945 Y 19551. Por Aida Velert Hernández 1 La información que ofrezco en este artículo procede del Trabajo Fin de Grado Superior en la Especialidad de Piano inédito que realicé bajo la dirección de la dra. Victoria Alemany y presenté al Departamento de Instrumentos Polifónicos del Conservatorio Superior de Música “Joaquín Rodrigo” de Valencia en 2013 [Velert (2013)]. Descubrí la Academia Marshall el curso 2003-2004, cuando iba a cumplir catorce años y fui aceptada como alumna en dicho centro sin ser en absoluto consciente al principio de su prestigio, y poco a poco me fue fascinando lentamente. Una entidad que ha sido capaz de mantenerse firme e imperturbable durante más de una centuria, que ha sido testigo directo de los cambios/transformaciones sociopolíticas2 y económicas del país resistiendo embistes y contratiempos, y que ha logrado formar a algunos de los pianistas más relevantes del siglo XX en España, estimo que merece ser estudiada en profundidad. En definitiva, decidí abordar la investigación sobre un período de la existencia de esta academia en mi Trabajo Fin de Grado Superior por el respeto y la admiración que siento hacia esta institución, que se han ido acrecentando con el paso del tiempo. Facilitó mi tarea contar con abundante información aportada gentilmente por el Centro Documental de la Academia Marshall (CEDAM), por lo que quiero en primer lugar agradecer sinceramente al personal de administración de la Academia, y en especial a su directora de gestión doña Cintia Matamoros3, su confianza y la inestimable ayuda que me han brindado de forma desinteresada en todo momento. -

El Piano De Enrique Granados

CICLO EL PIANO DE ENRIQUE GRANADOS Noviembre 1991 CICLO EL PIANO DE ENRIQUE GRANADOS CICLO EL PIANO DE ENRIQUE GRANADOS Noviembre 1991 ÍNDICE Pág. Presentación 5 Programa general 7 Introducción general, por Antonio Fernández-Cid 11 Notas al Programa: • Primer concierto 24 • Segundo concierto 29 • Tercer concierto 34 Participantes 39 Está aún por estudiar seriamente el piano español del siglo XIXy comienzos del XX. Son innumerables las obras conservadas y muy a menudo editadas, pero rara vez se escuchan en concierto. Algunos de nuestros ciclos han querido subsanar esta laguna, como los dedicados al Piano romántico español o al Piano nacionalista español. Por lo poco que sabemos, el papel que jugaron en los años finales del siglo pasado y en los comienzos del presente los pianistas-compositores Isaac Albéniz y Enrique Granados fue fundamental en la superación de la música de salón hacia formas pianísticas de validez universal. la Suite Iberia y Goyescas son hitos de nuestra música, pero fueron conseguidos a través de un esfuerzo constante e inteligente que sigue siendo sistemáticamente preterido. El 75 aniversario de la muerte ele Enrique Granados nos da sobrado motivo para repasar la casi totalidad de la música pianística (sólo quedan al margen obras menores recientemente descubiertas y aún no editadas). Las colecciones más célebres (Danzas españolas y Goyescas) se reparten entre los tres conciertos del ciclo para que en cada uno de ellos tengamos ocasión de compararlas con otras obras menos ambiciosas, siempre encantadoras, pero sin las cuales el compositor de Lérida, tan enamorado del Madrid castizo, no hubiera alcanzado su completa madurez.