Enrique Granados' Piano Suite Goyescas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selected Intermediate-Level Solo Piano Music Of

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Selected intermediate-level solo piano music of Enrique Granados: a pedagogical analysis Harumi Kurihara Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Kurihara, Harumi, "Selected intermediate-level solo piano music of Enrique Granados: a pedagogical analysis" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3242. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3242 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SELECTED INTERMEDIATE-LEVEL SOLO PIANO MUSIC OF ENRIQUE GRANADOS: A PEDAGOGICAL ANALYSIS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Harumi Kurihara B.M., Loyola University, New Orleans, 1993 M.M.,University of New Orleans, 1997 August, 2005 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere appreciation to my major professor, Professor Victoria Johnson for her expert advice, patience, and commitment to my monograph. Without her help, I would not have been able to complete this monograph. I am also grateful to my committee members, Professors Jennifer Hayghe, Michael Gurt, and Jeffrey Perry for their interest and professional guidance in making this monograph possible. I must also recognize the continued encouragement and support of Professor Constance Carroll who provided me with exceptional piano instruction throughout my doctoral studies. -

Miguel Metzeltin LOS TEXTOS CRONÍSTICOS AMERICANOS

Miguel Metzeltin LOS TEXTOS CRONÍSTICOS AMERICANOS COMO FUENTES DEL CONOCIMIENTO DE LA VARIACIÓN LINGÜÍSTICA 1. Tres fuentes Para las observaciones y reflexiones lingüísticas que propongo en esta comunicación me baso en tres textos: Bernal Díaz del Castillo (21942), Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España, Madrid, Espasa-Calpe (edición de Carlos Pereyra); - Fr. Reginaldo de Lizárraga (1909), Descripción breve de toda la tierra del Perú, Tucumán, Río de la Plata y Chile, en: Serrano y Sanz, Manuel, Historiadores de Indias, Madrid, Bailly-Baillière (N.B.A.E. 15, 485-660); Relación geográfica de San Miguel de las Palmas de Tamalameque, Gobernación de Santa Marta, Audiencia de Nueva Granada, Virreinato del Perú (hoy República de Colombia), en: Latorre, Germán (ed.) (1919), Relaciones geográficas de Indias, Sevilla, Zarzuela, 9-34. Bernal Díaz del Castillo (1495-1581) nació en Medina del Campo, pasó a América en 1514, donde se quedó hasta su muerte. Fue testigo ocular de lo que cuenta. Su manera de escribir se considera cercana a la lengua hablada: le faltaba el sentido de la forma literaria [...]. La forma literaria que sí maneja, y bien, es la del relato: revive el pasado minuto por minuto, y lo describe confundiendo lo esencial con lo accidental, como en una vivaz conversación (E. Anderson Imbert 51965, 34). Escribió la historia a sus ochenta años. Reginaldo de Lizárraga y Obando nació en Medellin (Badajoz) en 1540, pasó a Quito a los quince años, entró en la orden dominicana, ejerció varios 143 Miguel Metzeltin cargos eclesiásticos, por último el de obispo de La Asunción, donde murió (1615). -

An Investigation of the Sonata-Form Movements for Piano by Joaquín Turina (1882-1949)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository CONTEXT AND ANALYSIS: AN INVESTIGATION OF THE SONATA-FORM MOVEMENTS FOR PIANO BY JOAQUÍN TURINA (1882-1949) by MARTIN SCOTT SANDERS-HEWETT A dissertatioN submitted to The UNiversity of BirmiNgham for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC DepartmeNt of Music College of Arts aNd Law The UNiversity of BirmiNgham September 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT Composed between 1909 and 1946, Joaquín Turina’s five piano sonatas, Sonata romántica, Op. 3, Sanlúcar de Barrameda, Op. 24, Sonata Fantasía, Op. 59, Concierto sin Orquesta, Op. 88 and Rincón mágico, Op. 97, combiNe established formal structures with folk-iNspired themes and elemeNts of FreNch ImpressioNism; each work incorporates a sonata-form movemeNt. TuriNa’s compositioNal techNique was iNspired by his traiNiNg iN Paris uNder ViNceNt d’Indy. The unifying effect of cyclic form, advocated by d’Indy, permeates his piano soNatas, but, combiNed with a typically NoN-developmeNtal approach to musical syNtax, also produces a mosaic-like effect iN the musical flow. -

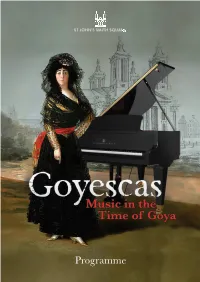

Music in the Time of Goya

Music in the Time of Goya Programme ‘Goyescas’: Music in the Time of Goya Some of the greatest names in classical music support the Iberian and Latin American Music Society with their membership 2 November 2016, 7.00pm José Menor piano Daniel Barenboim The Latin Classical Chamber Orchestra featuring: Argentine pianist, conductor Helen Glaisher-Hernández piano | Elena Jáuregui violin | Evva Mizerska cello Nicole Crespo O’Donoghue violin | Cressida Wislocki viola and ILAMS member with special guest soloists: Nina Corti choreography & castanets Laura Snowden guitar | Christin Wismann soprano Opening address by Jordi Granados This evening the Iberian and Latin American Music Society (ILAMS) pays tribute to one of Spain’s most iconic composers, Enrique Granados (1867–1916) on the centenary year of his death, with a concert programme inspired by Granados’ greatest muse, the great Spanish painter Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828), staged amidst the Baroque splendour of St John’s Smith Square – a venue which, appropriately, was completed not long before Goya’s birth, in 1728. Enrique Granados To pay homage to Granados here in London also seems especially fi tting given that the great Composer spent his fi nal days on British shores. Granados Will you drowned tragically in the English Channel along with his wife Amparo after their boat, the SS Sussex, was torpedoed by the Germans. At the height of his join them? compositional powers, Granados had been en route to Spain from New York where his opera, Goyescas, had just received its world premiere, and where he had also given a recital for President Woodrow Wilson; in his lifetime Granados was known as much for his virtuoso piano playing as for his talent as a composer. -

La Zarzuela En Un Acto: Música Representada

Recitales para Jóvenes de la FUNDACIÓN JUAN MARCH Curso 201 3/201 4 La zarzuela en un acto: música representada Guía didáctica para el profesor Presentador: Ignacio Jassa o Polo Vallejo Guía didáctica: Alberto González Lapuente @ Alberto González Lapuente, 2013. (ijl Fundación Juan March - Dcparcamcnto de Actividades Culturales, 2013. Los textos contenidos en esta GuÍél Didáctica pueden reproducirse libremente citando la procedem:ia y los autores de la misma. Diseño de la Guía: Gonzalo Fernández .\'lonte. \\'WW.march.es La zarzuela en un acto: música representada e réditos LA SALSA DE ANICETA Zarzuela en un acto Música de Ángel Rubio y libreto de Rafael María Liern Estrenada el 3 de abril de 1879 en el Teatro de Apolo, Madrid Primera interpretación en tiempos modernos Real Escuela Superior de Arte Dramático Con la colaboración de la R ESAD Dirección de escena: Claudia Tobo Escenografía: Marcos Carazo Acero Vestuario: María Arévalo Iluminación: Nuria Henríquez Reparto Doña Presentación, tiple cómica: Paula lwasaki Elvira, soprano: María Rodríguez o Ruth lniesta Don Gumersindo, actor cantante: Raúl Novillo Alfredo, tenor: Julio Morales o Emilio Sánchez Piano: Celsa Tamayo o Miguel Huertas ~ - ":::::: FUNDACIÓN JUAN MARCH Recitales para Jóvenes • Gu ía didáctica La zarzuela en un acto: música representada 2 La zarzuela: una aproximación Características generales .............................................................................................................. 4 Área de influencia .......................................................................................................................... -

Granados: Goyescas

Goyescas Enrique Granados 1. Los Requiebros [9.23] 2. Coloquio en La Reja [10.53] 3. El Fandango de Candil [6.41] 4. Quejas, ó la Maja y el Ruiseñor [6.22] 5. El Amor y la Muerte: Balada [12.43] 6. Epilogo: Serenata del Espectro [7.39] Total Timings [54.00] Ana-Maria Vera piano www.signumrecords.com The Goyescas suite has accompanied me throughout with her during the recording sessions and felt G my life, and I always knew that one day I would generous and grounded like never before. The music attempt to master it.The rich textures and came more easily as my perspectives broadened aspiring harmonies, the unfurling passion and I cared less about perfection. Ironically this is tempered by restraint and unforgiving rhythmic when you stand the best chance of approaching precision, the melancholy offset by ominous, dark your ideals and embracing your audience. humour, the elegance and high drama, the resignation and the hopefulness all speak to my sense of © Ana-Maria Vera, 2008 being a vehicle, offeeling the temperature changes, the ambiguity, and the emotion the way an actor might live the role of a lifetime. And so this particular project has meant more to me than almost any in my career. Catapulted into the limelight as a small child, I performed around the globe for years before realising I had never had a chance to choose a profession for myself. Early success, rather than going to my head, affected my self-confidence as a young adult and I began shying away from interested parties, feeling the attention wasn't deserved and therefore that it must be of the wrong kind. -

Popular, Elite and Mass Culture? the Spanish Zarzuela in Buenos Aires, 1890-1900

Popular, Elite and Mass Culture? The Spanish Zarzuela in Buenos Aires, 1890-1900 Kristen McCleary University of California, Los Angeles ecent works by historians of Latin American popular culture have focused on attempts by the elite classes to control, educate, or sophisticate the popular classes by defining their leisure time activities. Many of these studies take an "event-driven" approach to studying culture and tend to focus on public celebrations and rituals, such as festivals and parades, sporting events, and even funerals. A second trend has been for scholars to mine the rich cache of urban regulations during both the colonial and national eras in an attempt to mea- sure elite attitudes towards popular class activities. For example, Juan Pedro Viqueira Alban in Propriety and Permissiveness in Bourbon Mexico eloquently shows how the rules enacted from above tell more about the attitudes and beliefs of the elites than they do about those they would attempt to regulate. A third approach has been to examine the construction of national identity. Here scholarship explores the evolution of cultural practices, like the tango and samba, that developed in the popular sectors of society and eventually became co-opted and "sanitized" by the elites, who then claimed these activities as symbols of national identity.' The defining characteristic of recent popular culture studies is that they focus on popular culture as arising in opposition to elite culture and do not consider areas where elite and popular culture overlap. This approach is clearly relevant to his- torical studies that focus on those Latin American countries where a small group of elites rule over large predominantly rural and indigenous populations. -

Repertoire Report 2012-13 Season Group 7 & 8 Orchestras

REPERTOIRE REPORT 2012-13 SEASON GROUP 7 & 8 ORCHESTRAS Composer Work First Perf. Conductor Orchestra Soloist(s) Actor, Lee DIVERTIMENTO FOR SMALL ORCHESTRA Apr. 27, 2013 Emily Ray Mission Chamber Orchestra Adams, John SHORT RIDE IN A FAST MACHINE Oct. 13, 2012 Fouad Fakhouri Fayetteville Symphony Orchestra Bach, J. S. TOCCATA AND FUGUE, BWV 565, D MINOR Oct. 27, 2012 Charles Latshaw Bloomington Symphony (STOWKOWSKI) (STOWKOWSKI,) Orchestra Barber, Samuel CONCERTO, VIOLIN AND ORCHESTRA, Feb. 2, 2013 Jason Love The Columbia Orchestra Madeline Adkins, violin OPUS 14 Barber, Samuel OVERTURE TO THE SCHOOL FOR Feb. 9, 2013 Herschel Kreloff Civic Orchestra of Tucson SCANDAL Bartok, Béla ROMANIAN FOLK DANCES Sep. 29, 2012 Steven Lipsitt Boston Classical Orchestra Beethoven, Ludwig V. CONCERTO, PIANO, NO. 5 IN E-FLAT Apr. 14, 2013 Joel Lazar Symphony of the Potomac Sayaka Jordan, piano MAJOR, OP. 73 Beethoven, Ludwig V. CONCERTO, VIOLIN, IN D MAJOR, OPUS Nov. 17, 2012 Steven Lipsitt Boston Classical Orchestra Sharon Roffman, violin 61 Beethoven, Ludwig V. CORIOLAN: OVERTURE, OPUS 62 Mar. 9, 2013 Fouad Fakhouri Fayetteville Symphony Orchestra Apr. 14, 2013 Joel Lazar Symphony of the Potomac Beethoven, Ludwig V. EGMONT: OVERTURE, OPUS 84 Oct. 20, 2012 Steven Lipsitt Boston Classical Orchestra Beethoven, Ludwig V. SONATA FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO, Apr. 13, 2013 Steven Lipsitt Boston Classical Orchestra "SPRING" III RONDO Beethoven, Ludwig V. SYMPHONY NO. 1 IN C MAJOR, OPUS 21 Apr. 27, 2013 Emily Ray Mission Chamber Orchestra Beethoven, Ludwig V. SYMPHONY NO. 3 IN E-FLAT MAJOR, Apr. 14, 2013 Joel Lazar Symphony of the Potomac OPUS 55 Page 1 of 13 REPERTOIRE REPORT 2012-13 SEASON GROUP 7 & 8 ORCHESTRAS Composer Work First Perf. -

María Del Carmen Opera in Three Acts

Enrique GRANADOS María del Carmen Opera in Three Acts Veronese • Suaste Alcalá • Montresor Wexford Festival Opera Chorus National Philharmonic Orchestra of Belarus Max Bragado-Darman CD 1 43:33 5 Yo también güervo enseguía Enrique (Fuensanta, María del Carmen) 0:36 Act 1 6 ¡Muy contenta! y aquí me traen, como aquel GRANADOS 1 Preludio (Orchestra, Chorus) 6:33 que llevan al suplicio (María del Carmen) 3:46 (1867-1916) 2 A la paz de Dios, caballeros (Andrés, Roque) 1:28 7 ¡María del Carmen! (Pencho, María del Carmen) 5:05 3 Adiós, hombres (Antón, Roque) 2:27 8 ¿Y qué quiere este hombre a quien maldigo María del Carmen 4 ¡Mardita sea la simiente que da la pillería! desde el fondo de mi alma? (Pepuso, Antón) 1:45 (Javier, Pencho, María del Carmen) 4:10 Opera in Three Acts 9 5 ¿Pos qué es eso, tío Pepuso? ¡Ah!, tío Pepuso, lléveselo usted (Roque, Pepuso, Young Men) 3:04 (María del Carmen, Pepuso, Javier, Pencho) 0:32 Libretto by José Feliu Codina (1845-1897) after his play of the same title 0 6 ¡Jesús, la que nos aguarda! Ya se fue. Alégrate corazón mío Critical Edition: Max Bragado-Darman (Don Fulgencio, Pepuso, Roque) 1:49 (María del Carmen, Javier) 0:55 ! ¡Viva María el Carmen y su enamorao, Javier! Published by Ediciones Iberautor/Instituto Complutense de Ciencias Musicales 7 Una limosna para una misa de salud… (Canción de la Zagalica) (María del Carmen, (Chorus, Domingo) 5:22 @ ¡Pencho! ¡Pencho! (Chorus) ... Vengo a delatarme María del Carmen . Diana Veronese, Soprano Fuensanta, Don Fulgencio, Pepuso, Roque) 6:59 8 Voy a ver a mi enfermo, el capellán para salvar a esta mujer (Pencho, Domingo, Concepción . -

Pasodoble PSDB

Documentación técnica Pasodoble PSDB l Pasodoble, o Paso Doble, es un baile que se originó en España entre 1533 y E1538. Podría ser considerado, en esen- cia, como el estandarte sonoro que le distingue en todas partes del mundo. Se trata de un ritmo alegre, pleno de brío, castizo, flamenco unas veces, pero siempre reflejo del garbo y más ge- nuino sabor español. Se trata de una variedad musical dentro de la forma «marcha» en com- pás binario de 2/4 o 6/8 y tiempo «allegro mo- derato», frecuentemente compuesto en tono menor, utilizada indistintamente para desfiles militares y para espectáculos taurinos. Aunque no está del todo claro, parece ser que el pasodoble tiene sus orígenes en la tonadilla escénica, –creada por el flautista es- pañol Luis de Misón en 1727– que era una Este tipo de macha ligera fue adoptada composición que en la primera mitad del siglo como paso reglamentario para la infantería es- XVII servía como conclusión de los entreme- pañola, en la que su marcha está regulada en ses y los bailes escénicos y que después, 120 pasos por minuto, con la característica es- desde mediados del mismo siglo, se utilizaba pecial que hace que la tropa pueda llevar el como intermedio musical entre los actos de las paso ordinario. Tras la etapa puramente militar comedias. –siglo XVIII– vendría la fase de incorporación de elementos populares –siglo XIX–, con la El pasodoble siempre ha estado aso- adición de elementos armónicos de la seguidi- ciado a España y podemos decir que es el baile lla, jota, bolero, flamenco.. -

Crying Across the Ocean: Considering the Origins of Farruca in Argentina Julie Galle Baggenstoss March 22, 2014 the Flamenco

Crying Across the Ocean: Considering the Origins of Farruca in Argentina Julie Galle Baggenstoss March 22, 2014 The flamenco song form farruca is popularly said to be of Celtic origin, with links to cultural traditions in the northern Spanish regions of Galicia and Asturias. However, a closer look at the song’s traits and its development points to another region of origin: Argentina. The theory is supported by an analysis of the song and its interpreters, as well as Spanish society at the time that the song was invented. Various authors agree that the song’s traditional lyrics, shown in Table 1, exhibit the most obvious evidence of the song’s Celtic origin. While the author of the lyrics is not known, the word choice gives some clues about the person who wrote them. The lyrics include the words farruco and a farruca, commonly used outside of Galicia to refer to a person who is from that region of Spain. The use of the word farruco/a indicates that the author was not in Galicia at the time the song was written. Letra tradicional de farruca Una Farruca en Galicia amargamente lloraba porque a la farruca se le había muerto el Farruco que la gaita le tocaba Table 1: Farruca song lyrics Sources say the poetry likely expresses nostalgia for Galicia more than the perspective of a person in Galicia (Ortiz). A large wave of Spanish immigrants settled in what is now called the Southern Cone of South America, including Argentina and Uruguay, during the late 19th century, when the flamenco song farruca was first documented as a sung form of flamenco. -

El Piano De Enrique Granados

CICLO EL PIANO DE ENRIQUE GRANADOS Noviembre 1991 CICLO EL PIANO DE ENRIQUE GRANADOS CICLO EL PIANO DE ENRIQUE GRANADOS Noviembre 1991 ÍNDICE Pág. Presentación 5 Programa general 7 Introducción general, por Antonio Fernández-Cid 11 Notas al Programa: • Primer concierto 24 • Segundo concierto 29 • Tercer concierto 34 Participantes 39 Está aún por estudiar seriamente el piano español del siglo XIXy comienzos del XX. Son innumerables las obras conservadas y muy a menudo editadas, pero rara vez se escuchan en concierto. Algunos de nuestros ciclos han querido subsanar esta laguna, como los dedicados al Piano romántico español o al Piano nacionalista español. Por lo poco que sabemos, el papel que jugaron en los años finales del siglo pasado y en los comienzos del presente los pianistas-compositores Isaac Albéniz y Enrique Granados fue fundamental en la superación de la música de salón hacia formas pianísticas de validez universal. la Suite Iberia y Goyescas son hitos de nuestra música, pero fueron conseguidos a través de un esfuerzo constante e inteligente que sigue siendo sistemáticamente preterido. El 75 aniversario de la muerte ele Enrique Granados nos da sobrado motivo para repasar la casi totalidad de la música pianística (sólo quedan al margen obras menores recientemente descubiertas y aún no editadas). Las colecciones más célebres (Danzas españolas y Goyescas) se reparten entre los tres conciertos del ciclo para que en cada uno de ellos tengamos ocasión de compararlas con otras obras menos ambiciosas, siempre encantadoras, pero sin las cuales el compositor de Lérida, tan enamorado del Madrid castizo, no hubiera alcanzado su completa madurez.