Answering That Proverbial Question

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Olivera Grbić Cuisine

SerbianOlivera Grbić Cuisine Translated from Serbian by: Vladimir D. Janković ALL TRADITIONAL PLATES Belgrade, 2012. dereta Olivera Grbić SERBIAN CUISINE Translated from Serbian by Vladimir D. Janković Original title Srpska kuhinja Editor-in-Chief: Dijana Dereta Edited by: Aleksandar Šurbatović Artistic and Graphic Design: Goran Grbić ISBN 978-86-7346-861-7 Print run: 1000 copies Belgrade, 2012. Published / Printed / Marketed by: Grafički atelje DERETA Vladimira Rolovića 94a, 11030, Belgrade e-mail: [email protected] Phone / Fax: 381 11 23 99 077; 23 99 078 www.dereta.rs © Grafički Atelje Dereta DERETA Bookstores Knez Mihailova 46, Belgrade; phone: +381 11 30 33 503; 26 27 934 Dostojevskog 7, Banovo Brdo, Belgrade, phone: 381 30 58 707; 35 56 445 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 9 COLD APPETIZERS 11 NISH STYLE ASPIC 12 STERLET ASPIC 13 BEAN ASPIC 15 HOOPLA (URNEBES) SALAD 16 SOUPS AND BROTHS 19 PICKLED PEPPERS STUFFED WITH CHEESE AND KAYMAK 17 DOCK BROTH 21 LEEK AND CHICKEN BROTH 23 SOUR LAMB SOUP 22 POTATO BROTH 25 PEA BROTH 26 BEAN BROTH 27 BEEF SOUP 29 VEAL BROTH 31 DRIED MEAT SOUP 30 HOT APPETIZERS 35 FISH SOUP 33 FRITTERS 36 TSITSVARA 37 CORNBREAD 39 POLENTA WITH CHEESE 40 MANTLES 41 POTATO DOUGHNUT 43 MEAT PIE 44 GIBANITZA 45 SPINACH PIE 47 SCRAMBLED EGGS WITH CHEESE & ROASTED PEPPERS 48 SCRAMBLED EGGS WITH CRACKLINGS 49 SAUERKRAUT PIE 51 POTATOES WITH CHEESE 52 CHEESE STUFFED PEPPERS 53 BREADED FRIED PEPPERS 55 CORN FLOUR PANCAKE 56 UZICE STYLE PUFF PASTRIES 57 MEATLESS DISHES 61 LARD MUFFINS 59 LENTILS WITH RICE 62 BACHELOR STEW 63 BAKED -

Faculty of Tourism

FACULTY OF TOURISM Anadolu University, School of Tourism and Hotel Management was established in 1993. After a one-year preparatory school, Anadolu University, School of Tourism and Hotel Management offers a Bachelor of Arts degree upon completion of an eight semester program. Students have the opportunity of studying in the laboratories and participate in various facilities of operations via highly widespread package programs; such as Fidelio, Amadeus and Galileo. A compulsory industrial training period of minimum 90 workdays is also a part of the study. As a principle, it is a great concern for the school that students should undergo the training period in 3-4-5 star hotels, 4-5 star holiday villages, tour operators and travel agencies. While preparing the program, industrial needs are taken into consideration. Since the students are accepted as the candidate managers of the future, they both take the occupational courses of the school as well as courses similar in content to the ones in Faculty of Business Administration. The school also offers programs leading to the Master of Arts and Philosophy of Doctorate degrees. Double major programs involving two departments within the university could be majored by the students who are allowed to according to their grades. Beside these degree programs, the school also houses the "e-Tourism Management" program for a Master's degree. Since 2003 EI-AH&LA American Hotel and Lodging Management Certificate Program is available for college level students to provide them with vocational scholastic -

Jo's Fatayer & Lebanese Salad Baklava

RECIPE INDEX ! EPISODE 01 Jo’s Fatayer & refrigerate for up to 8 hours. Baklava 2. Position racks in the top third and Lebanese Salad middle of the oven and preheat the from Magnolia Table, Volume 2 Cookbook from the Magnolia Table Cookbook oven to 350°F. Line two baking sheets with parchment paper. prep: 40 minutes cook: under 45 minutes 30 minutes 40 minutes prep: cook: to make the fatayar at least 4 hours cool: none cool: 3. In a large sauté pan, heat the oil over medium-high heat. Add the onion and 1!⁄# cups (8 ounces) whole raw almonds, lebanese salad cook, stirring o!en, until so!ened, toasted 4 large vine-ripened tomatoes, cut into about 3 minutes. Add the beef and 1%⁄& cups (8 ounces) raw pistachios, plus 3 !⁄"-inch dice cook, stirring o!en to break up the tablespoons chopped toasted pistachios 4 English cucumbers, cut into 1⁄4-inch dice meat, until no longer pink, about 6 !⁄" cup sugar !⁄# cup minced white onion (optional) minutes. Pour o" any standing liquid. 1 teaspoon ground cardamom Juice of 1 lemon Stir in the hash browns, Cheddar, 2 1 teaspoon ground cinnamon !⁄" cup extra virgin olive oil !⁄" teaspoon ground nutmeg 1 teaspoon kosher salt teaspoons salt, and the pepper. Stir !⁄" teaspoon kosher salt !⁄# teaspoon freshly ground black pepper until well combined. Taste and adjust the seasoning. Set aside. 1!⁄" cups (2 1/2 sticks) unsalted butter, melted fatayar 4. Open the cans of biscuits and One 16-ounce package frozen phyllo dough, 1 tablespoon extra virgin olive oil separate the dough into individual thawed !⁄" cup minced white onion biscuits (24 total). -

Beatnik Dinner Menu Inside

SMALL PLATES HALLOUMI CHEESE $9 GRILLED BABY SEPIA $15 Tomato & Quince Jam, Preserved Lemon Yogurt,Oregano Squid Ink Masa Dumplings, Smoked Tomato Sugo, Lemongrass, Corn CHEESE DUMPLINGS $14 Ricotta & Idiazábal Cheese Dumplings, FRIED QUAIL $14 Seasonal Market Vegetables, Saffron Broth, Duck Egg Lentil Salad, Preserved Lemon Salsa Brava, Cilantro GRILLED OYSTERS $14 BEET HUMMUS $9 Shakshuka Verde, Egg Yolk Jam, Chili Powder Blue Cheese, Roasted Pepitas, Fried Garbanzo, Basil Oil, Served With Pita Bread POTATOES 3 WAYS $12 Leek Labneh, Allium Salad, Caviar RABBIT AREPA $14 Tamarind Braised Rabbit, Liver Crema, Olives, SCALLOP CRUDO $14 Market Salad, Rabbit Jus Peach & Hibiscus Aguachile, Hearts Of Palm, Seasonal Market Fruit, Sesame & Chia Seeds MUSSELS MERGUEZ $13 Housemade Merguez Sausage, Black Ale Beer, CURRY MEATBALLS $12 Fennel, Grilled Ciabatta English Pea Purée, Sun Dried Tomatoes, Cilantro THE FEAST ROASTED LEBANESE STYLE LAMB $55 Pistachio Tzatziki, Sherry Vinegar Pickled Radishes, Garbanzo Bean Salad, Roti Bread 50oz TOMAHAWK STEAK $95 Nopales Salad, Black Garlic Chimichurri WHOLE FISH $32 Pan Roasted, Kerala Curry, Green Mango Salad SMOKED & ROASTED CAPON $36 Harissa & Black Ale Beer Marinated, Pearl Onions, Grilled Lemon PLUMA IBÉRICA $48 10 Day Dry Aged, Roasted Sweet Potato Purée, Japanese Pickled Plums, Grilled Summer Melon MEZZE CHARRED BROCCOLINI $8 ROASTED BUTTERNUT SQUASH $8 Nuoc Cham, Sunflower Hummus, Pomegranate Seeds, Jalapeño & Cilantro Yogurt, Pepitas Puffed Rice FATTOUSH SALAD $11 GRILLED ASPARAGUS $7 Persian -

Meni TABOR EDIT 2016

RED WINES TRI MORAVE - Temet, 14,5% - Jagodina, Srbija 0.75l 2250 PROKUPAC - Ivanovic, 13,2% - Župa, Srbija 0.75l 2100 KREMEN - Matalj, 12,5% - Negotin, Srbija 0.75l 2200 CABERNET & MERLOT - Cilić, 13,5% - Jagodina, Srbija 0.75l 2350 CRVENI ZAPIS - Janko, 14% - Smederevo, Srbija 0.75l 2200 ŽIVOT TEČE - Zvonko Bogdan, 12% - Palić, Srbija 0.75l 2400 MONTEPULCIANO - Marina Cvetić, 14,5% - Abruzzo, Italija 0.75l 4650 CABERNET SAUVIGNON - Radovanović, 12,5% - Krnjevo, Srbija 0.75l 2000 TVRDOŠKO CRNO - Manastir Tvrdoš, 12% - Trebinje, BIH 0.75l 2550 ZLATAN PLAVAC GRAND CRU - Plenković, 15% - Hvar, Hrvatska 0.75l 9000 BRUNELLO DI MONTALCINO - Casanova di Neri, 14,5% - Toscana, Italija 0.75l 9200 AURELIUS - Kovačević, 13,5%, Irig, Srbija 0.75l 2250 CHIANTI SUPERIORE D.O.C.G, Santa Cristina, 13% - Toscana, Italija 0.75l 2350 CABERNET - 13. jul Plantaže, 12,5% - Podgorica, Crna Gora 0.75l 1200 VRANAC PRO CORDE - 13. jul Plantaže, 12,5% - Podgorica, Crna Gora 0.75l 1700 VRANAC - 13. jul, 12,5% - Podgorica, Crna Gora 0.75l 1050 VRANAC - 13. jul, 12,5% - Podgorica, Crna Gora 0.187l 390 DINGAČ - Matuško, 14,2% - Pelješac, Hrvatska 0.75l 4800 POSTUP - Matuško, 13,3% - Pelješac, Hrvatska 0.75l 4650 KRATOŠIJA - Tikveš, 12% - Tikvesko vinogorje, Makedonija 0.75l 1050 MALBEC - Chakana, 14% - Mendoza, Argentina 0.75l 2250 MALBEC RESERVA - Chakana, 13,9% - Mendoza, Argentina 0.75l 2900 CABERNET SAUVIGNON RESERVA - Chakana, 14,5% - Mendoza, Argentina 0.75l 2900 FABULA LAGUM - Chichateau 14,5% - Šišatovac, Srbija 0.75l 3400 GRAFFITI - Bjelica 14%, Novi Sad, Srbija 0.75l 2990 BAMBINO NERO - Chichateau 13% - Šišatovac, Srbija 0.75l 1900 REGENT - Aleksandrović 13,5% - Topola, Srbija 0.75l 2700 VLADIKA - 13, Jul Plantaže 14% - Podgorica, Crna Gora 0.75l 2250 TGA ZA JUG -Tikveš 12,5% - Tikveš, Makedonija 0.75l 1200 DAILY MENU 1. -

Clubmarko 2019.Cdr

IZ NAŠE KUHINJE FROM OUR KITCHEN DORUCAK BREAKFAST PREDJELA APPETIZERS Američki doručak Tanjir „Švajcarija“ Dva jaja pripremljena po Vašem izboru (pržena, kuvana Selekcija najfinijeg Njeguškog i goveðeg pršuta i buðole ili kajgana) sa kobasicom, hrskavom slaninom, sa brie sirom i bademom. 1190,00 pečurkama i krompirom. 450,00 „Švajcarija“ Plate American Breakfast Selecon of finest prosciuo, dried beef and budjola Two eggs prepared according to your choice (fried, with brie cheese and almonds. boiled or scrambled) with sausage, crispy bacon, sautéed mushrooms and potatoes. Tanjir „Sky Lounge“ (za dve osobe) 1390,00 Selekcija goveđe pršute, kulena, suvog mesa sa kozijim Engleski doručak sirom i sosom od šumskog voća. Dva jaja pripremljena po Vašem izboru (pržena, kuvana “Sky Lounge“ plate (for two persons) ili kajgana) sa kobasicom, slaninom, pečurkama, Selecon of dried beef variees, goat cheese and pasuljem i tost hlebom. 450,00 forest fruits sauce. English Breakfast Two eggs prepared according to your choice with Mešani strani sirevi sausage, bacon, sautéed mushrooms, beans and toast Selekcija stranih sireva sa medom i voćem. 1190,00 bread. Mixed Imported Cheeses Selecon of imported cheeses with honey and fruits. OMLET Omlet od tri jaja pripremljen po Vašem izboru sa sirom, Pohovani sir 490,00 šunkom, slaninom, pečurkama ili povrćem. 290,00 Fried cheese OMELETTE Omelee made with three eggs according to your Mešani domaći sirevi 890,00 choice: cheese, ham, bacon, mushrooms or Mixed Local Cheeses vegetables. Rižoto sa ćurenom 590,00 Prženice Turkey Risoo Slane (feta sir, ajvar), Slatke (džem, eurokrem). 290,00 French toast Pileći štapići sa susamom With cheese (feta cheese, ajvar), Sweet (jam, Ukusne hrskave trake pohovanog pilećeg belog mesa sa eurocrem). -

Facts About Romania

FACTS ABOUT ROMANIA Romania Requirements for Visa and Entry Travel Documents American and Canadian citizens as well as citizens of Australia, New Zealand and most European countries do not need an entry visa to visit Romania, for stays up to 90 (ninety) days. However, a valid passport is required for all overseas/ non-EU visitors. Your passport has to be valid for the entire duration of your visit (it will not expire sooner than your intended date of departure). For stays longer than 90 days visitors need to contact a local passport office in Romania or a onsulate of Romania, to obtain a visa. Citizens of the countries of the European Union can enter Romania with a valid passport or with their National Identity Card. U.S. / Canadian/ Australian/ New Zealand and all European Driver licenses are valid for driving in Romania for 90 days from the date of entry into Romania. Citizens of any other country should check the visa regulations that apply to them with the nearest Romanian Consulate. More entry and visa information as well as a list of Romanian Consulates abroad are available at http://mae.ro/en/node/2040. There is no Entry or Departure Tax. List of countries whose nationals, bearer of a regular passport, are exempt from the requirement of a Romanian visa. List of countries whose nationals, bearer of diplomatic, service, official passport and seamen's books, are exempt from the requirement of a Romanian visa. List of countries whose nationals, holders of regular passport, need a visa to enter Romania. More information: http://romania.usembassy.gov/acs/romanian_visa.html Health No immunizations or unusual health precautions are necessary or required. -

Nycfoodinspectionsimple Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results

NYCFoodInspectionSimple Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results DBA BORO STREET ZIPCODE JJANG COOKS Queens ROOSEVELT AVE 11354 JUICY CUBE Manhattan LEXINGTON AVENUE 10022 DUNKIN Bronx BARTOW AVENUE 10469 BEVACCO RESTAURANT, Brooklyn HENRY STREET 11201 BINC LILI MEXICAN Bronx EAST 138 STREET 10454 RESTAURANT RUINAS DE COPAN Bronx BROOK AVENUE 10455 SHUN LI CHINESE Brooklyn PITKIN AVENUE 11212 RESTAURANT SUNFLOWER CAFE Manhattan 3 AVENUE 10010 Manhattan EAST 10 STREET 10003 CARIBBEAN & AMERICAN Brooklyn NOSTRAND AVENUE 11226 ENTERTAINMENT BAR LOUNGE & RESTAURANT NIZZA Manhattan 9 AVENUE 10036 OLIVE GARDEN Brooklyn GATEWAY DRIVE 11239 DAWA'S Queens SKILLMAN AVE 11377 FARIEDA'S DHAL PURI Queens 101ST AVE 11419 HUT GOOD TASTE 88 Brooklyn 52 STREET 11220 PIG AND KHAO Manhattan CLINTON STREET 10002 Page 1 of 556 09/26/2021 NYCFoodInspectionSimple Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results CUISINE DESCRIPTION INSPECTION DATE Korean 11/20/2019 Juice, Smoothies, Fruit Salads 02/23/2018 Donuts 11/29/2019 Italian 12/19/2018 Mexican 08/14/2019 Spanish 06/11/2018 Chinese 11/23/2018 American 02/07/2020 01/01/1900 Caribbean 02/08/2020 Italian 11/30/2018 Italian 09/25/2017 Coffee/Tea 04/17/2018 Caribbean 07/09/2019 Chinese 02/06/2020 Thai 02/12/2019 Page 2 of 556 09/26/2021 NYCFoodInspectionSimple Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results EMPANADA MAMA Manhattan ALLEN STREET 10002 FREDERICK SOUL HOLE Queens MERRICK BLVD 11422 GOLDEN STEAMER Manhattan MOTT STREET 10013 GOLDEN STEAMER Manhattan MOTT STREET -

LESSON NOTES Basic Bootcamp S1 #1 Self Introductions and Basic Greetings in Formal Romanian

LESSON NOTES Basic Bootcamp S1 #1 Self Introductions and Basic Greetings in Formal Romanian CONTENTS 2 Romanian 2 English 2 Vocabulary 2 Sample Sentences 3 Grammar 5 Cultural Insight # 1 COPYRIGHT © 2016 INNOVATIVE LANGUAGE LEARNING. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ROMANIAN 1. Recepţionist: Bună ziua , Doamnă. Mă numesc Paul Iordache. 2. D-na Popescu: Îmi pare bine, Domnule. Mă numesc Popescu Georgiana. 3. Recepţionist: Îmi pare bine, Doamnă. ENGLISH 1. Receptionist: Hello, madam. I'm Paul Iordache. 2. Mrs. Popescu: Nice to meet you, sir. I'm Popescu Georgiana. 3. Receptionist: Nice to meet you, Madam. VOCABULARY Romanian English Class bună ziua hello, good day adjective +noun Doamnă madam, lady noun Mă numesc… My name is… verb îmi pare bine nice to meet you phrasal verb, phrase SAMPLE SENTENCES Bună ziua Domnule Bună ziua Doamnă "Hello, sir." "Hello, madam." ROMANIANPOD101.COM BASIC BOOTCAMP S1 #1 - SELF INTRODUCTIONS AND BASIC GREETINGS IN FORMAL ROMANIAN 2 Mă numesc Nicoleta. Îmi pare bine să vă întâlnesc. "My name is Nicoleta." "I'm pleased to meet you." Bună tuturor! Îmi pare bine. "Hi everyone! Nice to meet you." GRAMMAR T he Focus of T his Lesson Is Introducing Yourself and Basic Greetings in Formal Romanian Bună ziua, Doamnă. "Hello, madam." Bine aţi venit ("Welcome") to the Romanian language basics. Introducing yourself is inevitable in any situation, but is actually quite easy! Let's start with the phrase bună ziua! Bună ziua ("Hello"/"Good day") For a more classical and frequent greeting, use bună ziua, which literally means "good day," but basically means "hello." You can use bună ziua anytime during the daytime, in any circumstance; whether you are speaking to a friend, an elderly person, or an unknown person in an informal or formal situation, use buna ziua. -

Meni Engleski

STARTERS CHEFS RECOMEDANTION 100% from Serbia Leskovacka Muckalica 1250 Two kings spreads 890 Bell pepper and tomatoes stew with pork file, chicken Beetroot humus, kajmak cheese with walnuts, spicy legs and pork sausages, potato pure and rice cream cheese with paprika Traditional Beef Cevapi 980 Grilled Serbian cheese 930 Beef kebabs, served with Kajmak , tomato & “Mirocki” cheese, arugula salad, dried apricot, roasted onion salsa and aromatic potatoes pine nuts Dried plum surprise 760 Pljeskavica 980 Breaded dried plum stuffed with smoked bacon and Beef and pork patty, stuffed with bacon and smoked kajmak , apple almond ice-cream, rakia cocktail sauce cheese, served with tomato and onion salad, roasted bell pepper and Somun bread Crispy Brussel sprouts 780 Grilled Brussel sprouts, dried garlic, aioli mayo and Karadjordjeva schnitzel 1500 pomegranate Breaded pork care, stuffed with Kajmak , served with sautéed bell peppers, potatoes and tartar dressing Beef tartare 1960 Diced beef, pearl onion, parmigiana chips, capers, Dijon CHARCOAL PREMIUM Smoked salmon mouse 1150 Cream goat and cow cheese, smoked salmon, cucum- Beef tenderloin 250g 2700 ber, lemon jelly T-Bone 750g 3990 Ribeye 700g 6990 Local cheese selection 1160 ½ roasted chicken 1kg 1600 Selection of local cheeses, jams, dried fruits and grissini Pork chop Tomahawk 350g 1550 Mezze plater for one and two 1280 / 2250 Local prosciutto and sausages, mix of cheeses, olives, Sauces: 250din - Demi-glace sauce/ Pepper sauce/ pickles, ajvar and dried fruits Cream chesee sauce / Chimichurri -

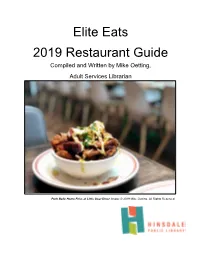

Elite Eats 2019 Restaurant Guide Compiled and Written by Mike Oetting

Elite Eats 2019 Restaurant Guide Compiled and Written by Mike Oetting, Adult Services Librarian Pork Belly Home Fries at Little Goat Diner. Image © 2019 Mike Oetting. All Rights Reserved Table of Contents Notes for the 2019 Edition..................................................................................................................... 3 Chinese .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Japanese (including Sushi and Ramen) .............................................................................................. 6 Korean ...................................................................................................................................................... 8 Thai........................................................................................................................................................... 9 Vietnamese ............................................................................................................................................ 11 Indian / South Asian ........................................................................................................................... 12 Middle Eastern and Mediterranean .................................................................................................. 14 Greek (New for 2019) ........................................................................................................................... 16 Italian -

Xmlns:W="Urn:Schemas-Microsoft-Com

Edit and Find may help in locating desired links. If links don’t work you can try copying and pasting into Netscape or Explorer Browser Definitions of International Food Related Items (Revised 2/14) [A] [B] [C] [D] [E] [F] [G] [H] [I] [J] [K] [L] [M] [N] [O] [P] [Q] [R] [S] [T] [U] [V] [W] [X] [Y] [Z] A Aaloo Baingan (Pakistani): Potato and aubergines (eggplant) Aaloo Ghobi (Paskistani): Spiced potato and cauliflower Aaloo Gosht Kari (Pakistani): Potato with lamb Aam (Hindu): Mango Aam Ka Achar (Indian): Pickled mango Aarici Halwa (Indian): A sweet made of rice and jaggery Abaisee: (French): A sheet of thinly rolled, puff pastry mostly used in desserts. Abalone: A mollusk found along California, Mexico, and Japan coast. The edible part is the foot muscle. The meat is tough and must be tenderized before cooking. Abats: Organ meat Abbacchio: Young lamb used much like veal Abena (Spanish): Oats Abenkwan (Ghanaian): A soup made from palm nuts and eaten with fufu. It is usually cooked with fresh or smoked meat or fish. Aboukir: (Swiss): Dessert made with sponge cake and chestnut flavored alcohol based crème. Abuage: Tofu fried packets cooked in sweet cooking sake, soy sauce, and water. Acapurrias (Spanish, Puerto Rico): Banana croquettes stuffed with beef or pork. Page 1 of 68 Acar (Malaysian): Pickle with a sour sweet taste served with a rice dish. Aceite (Spanish): Oil Aceituna: (Spanish): Olive Acetomel: A mixture of honey and vinegar, used to preserve fruit. Accrats (Hatian, Creol): Breaded fried cod, also called marinades. Achar (East Indian): Pickled and salted relish that can be sweet or hot.