Particularities of Media Systems in the West Nordic Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender Equality Policy in the Arts, Culture and Media Comparative Perspectives

Gender Equality Policy in the Arts, Culture and Media Comparative Perspectives Principal Investigator: Prof. Helmut K. Anheier, PhD SUPPORTED BY Project team: Charlotte Koyro Alexis Heede Malte Berneaud-Kötz Alina Wandelt Janna Rheinbay Cover image: Klaus Lefebvre, 2009 La Traviata (Giuseppe Verdi) @Dutch National Opera Season 2008/09 Contents Contents ...................................................................................................................................... 3 List of Figures .............................................................................................................................. 5 List of Tables ............................................................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgments .................................................................................................................... 8 Comparative Summary ............................................................................................................ 9 Introduction to Country Reports ......................................................................................... 23 Research Questions ......................................................................................................... 23 Method ............................................................................................................................... 24 Indicators .......................................................................................................................... -

Broadcasting & Convergence

1 Namnlöst-2 1 2007-09-24, 09:15 Nordicom Provides Information about Media and Communication Research Nordicom’s overriding goal and purpose is to make the media and communication research undertaken in the Nordic countries – Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden – known, both throughout and far beyond our part of the world. Toward this end we use a variety of channels to reach researchers, students, decision-makers, media practitioners, journalists, information officers, teachers, and interested members of the general public. Nordicom works to establish and strengthen links between the Nordic research community and colleagues in all parts of the world, both through information and by linking individual researchers, research groups and institutions. Nordicom documents media trends in the Nordic countries. Our joint Nordic information service addresses users throughout our region, in Europe and further afield. The production of comparative media statistics forms the core of this service. Nordicom has been commissioned by UNESCO and the Swedish Government to operate The Unesco International Clearinghouse on Children, Youth and Media, whose aim it is to keep users around the world abreast of current research findings and insights in this area. An institution of the Nordic Council of Ministers, Nordicom operates at both national and regional levels. National Nordicom documentation centres are attached to the universities in Aarhus, Denmark; Tampere, Finland; Reykjavik, Iceland; Bergen, Norway; and Göteborg, Sweden. NORDICOM Göteborg -

S12904-021-00797-0.Pdf

Bylund‑Grenklo et al. BMC Palliat Care (2021) 20:99 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904‑021‑00797‑0 CORRECTION Open Access Correction to: Acute and long‑term grief reactions and experiences in parentally cancer‑bereaved teenagers Tove Bylund-Grenklo1*†, Dröfn Birgisdóttir2*†, Kim Beernaert3,4, Tommy Nyberg5,6, Viktor Skokic6, Jimmie Kristensson2,7, Gunnar Steineck6,8, Carl Johan Fürst2 and Ulrika Kreicbergs9,10 Sciences, Gothenburg, Sweden. 9 Department of Caring Sciences, Palliative Correction to: BMC Palliat Care 20, 75 (2021) Research Center, Ersta Sköndal Bräcke University College, Stockholm, Sweden. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-021-00758-7 10 Department of Women’s and Children’s Health, Karolinska Institutet, Stock- Following publication of the original article [1], the holm, Sweden. authors identifed an error in the author name of Kim Beernaert. Te incorrect author name is: Kim Beenaert. Te correct author name is: Kim Beernaert. Te author group has been updated above and the orig- Reference inal article [1] has been corrected. 1. Bylund-Grenklo T, Birgisdóttir D, Beernaert K, et al. Acute and long- term grief reactions and experiences in parentally cancer-bereaved teenagers. BMC Palliat Care. 2021;20:75. https:// doi. org/ 10. 1186/ Author details s12904- 021- 00758-7. 1 Department of Caring Science, Faculty of Health and Occupational Studies, University of Gävle, 801 76 Gävle, Sweden. 2 Faculty of Medicine, Department of Clinical Sciences Lund, Oncology and Pathology, Institute for Palliative Care, Lund University and Region Skåne, Medicon Village, Hus 404B, 223 81 Lund, Sweden. 3 End-of-Life Care Research Group, Ghent University & Vrije Univer- siteit Brussel (VUB), Ghent, Belgium. -

Power, Communication, and Politics in the Nordic Countries

POWER, COMMUNICATION, AND POLITICS IN THE NORDIC COUNTRIES POWER, COMMUNICATION, POWER, COMMUNICATION, AND POLITICS IN THE NORDIC COUNTRIES The Nordic countries are stable democracies with solid infrastructures for political dia- logue and negotiations. However, both the “Nordic model” and Nordic media systems are under pressure as the conditions for political communication change – not least due to weakened political parties and the widespread use of digital communication media. In this anthology, the similarities and differences in political communication across the Nordic countries are studied. Traditional corporatist mechanisms in the Nordic countries are increasingly challenged by professionals, such as lobbyists, a development that has consequences for the processes and forms of political communication. Populist polit- ical parties have increased their media presence and political influence, whereas the news media have lost readers, viewers, listeners, and advertisers. These developments influence societal power relations and restructure the ways in which political actors • Edited by: Eli Skogerbø, Øyvind Ihlen, Nete Nørgaard Kristensen, & Lars Nord • Edited by: Eli Skogerbø, Øyvind Ihlen, Nete Nørgaard communicate about political issues. This book is a key reference for all who are interested in current trends and develop- ments in the Nordic countries. The editors, Eli Skogerbø, Øyvind Ihlen, Nete Nørgaard Kristensen, and Lars Nord, have published extensively on political communication, and the authors are all scholars based in the Nordic countries with specialist knowledge in their fields. Power, Communication, and Politics in the Nordic Nordicom is a centre for Nordic media research at the University of Gothenburg, Nordicomsupported is a bycentre the Nordic for CouncilNordic of mediaMinisters. research at the University of Gothenburg, supported by the Nordic Council of Ministers. -

Faroe Islands and Greenland 2008

N O R D I C M E D I A T R E N D S 10 Media and Communication Statistics Faroe Islands and Greenland 2008 Compiled by Ragnar Karlsson NORDICOM UNIVERSITY OF GOTHENBURG 2008 NORDICOM’s activities are based on broad and extensive network of contacts and collaboration with members of the research community, media companies, politicians, regulators, teachers, librarians, and so forth, around the world. The activities at Nordicom are characterized by three main working areas. Media and Communication Research Findings in the Nordic Countries Nordicom publishes a Nordic journal, Nordicom Information, and an English language journal, Nordicom Review (refereed), as well as anthologies and other reports in both Nordic and English langu- ages. Different research databases concerning, among other things, scientific literature and ongoing research are updated continuously and are available on the Internet. Nordicom has the character of a hub of Nordic cooperation in media research. Making Nordic research in the field of mass communication and media studies known to colleagues and others outside the region, and weaving and supporting networks of collaboration between the Nordic research communities and colleagues abroad are two prime facets of the Nordicom work. The documentation services are based on work performed in national documentation centres at- tached to the universities in Aarhus, Denmark; Tampere, Finland; Reykjavik, Iceland; Bergen, Norway; and Göteborg, Sweden. Trends and Developments in the Media Sectors in the Nordic Countries Nordicom compiles and collates media statistics for the whole of the Nordic region. The statistics, to- gether with qualified analyses, are published in the series, Nordic Media Trends, and on the homepage. -

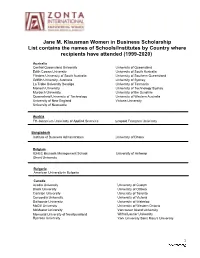

2020 JMK Schools

Jane M. Klausman Women in Business Scholarship List contains the names of Schools/Institutes by Country where recipients have attended (1999-2020) Australia Central Queensland University University of Queensland Edith Cowan University University of South Australia Flinders University of South Australia University of Southern Queensland Griffith University, Australia University of Sydney La Trobe University Bendigo University of Tasmania Monash University University of Technology Sydney Murdoch University University of the Sunshire Queensland University of Technology University of Western Australia University of New England Victoria University University of Newcastle Austria FH-Joanneum University of Applied Sciences Leopold Franzens University Bangladesh Institute of Business Administration University of Dhaka Belgium ICHEC Brussels Management School University of Antwerp Ghent University Bulgaria American University in Bulgaria Canada Acadia University University of Guelph Brock University University of Ottawa Carleton University University of Toronto Concordia University University of Victoria Dalhousie University University of Waterloo McGill University University of Western Ontario McMaster University Vancouver Island University Memorial University of Newfoundland Wilfrid Laurier University Ryerson University York University Saint Mary's University 1 Chile Adolfo Ibanez University University of Santiago Chile University of Chile Universidad Tecnica Federico Santa Maria Denmark Copenhagen Business School Technical University of Denmark -

The Shift from High to Liquid Ideals Making Sense of Journalism and Its Change Through a Multidimensional Model

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Göteborgs universitets publikationer - e-publicering och e-arkiv Nordicom Review 34 (2013) Special Issue, pp.141-154 The Shift from High to Liquid Ideals Making Sense of Journalism and Its Change through a Multidimensional Model Kari Koljonen Abstract By reading qualitative studies, surveys, organisational histories, and textbooks, one can claim that the ethos of journalists has undergone fundamental changes in recent decades. The “high modern” journalistic ethos of the 1970s and 1980s was committed to the core values of the journalistic profession: objectivity, public service, consensus maintenance, gate-keeping, and recording of the recent past. After the millennium, these central ideals have become more ambivalent and “liquid”: subjectivity, consumer service, the watchdog role, agenda-setting, and forecasting the future seem to be more tempting alternatives than before. This article develops an analytic framework that elaborates the simple narrative from “high modern” to “liquid modern” journalism. Five key elements, namely, (1) knowledge, (2) audience, (3) power, (4) time, and (5) ethics, are discussed and problematized to suggest a more nuanced view of the changing professional ethos of journalism. Keywords: journalistic profession, core elements of journalism, professional ethos, high/ liquid modern ideals, multidimensional model, analysis of change Introduction One of the most common ways of crafting normative, evaluative discourses is to con- struct a narrative of change. This has also been true in journalism research recently (e.g. McChesney & Nichols 2010, McChesney & Pickard 2011). However, because journalism is a multifaceted institution with many interfaces to its social, political, and economic contexts, many alternative narratives are possible. -

Faroe Islands and Greenland 2008

N O R D I C M E D I A T R E N D S 10 Media and Communication Statistics Faroe Islands and Greenland 2008 Compiled by Ragnar Karlsson NORDICOM UNIVERSITY OF GOTHENBURG 2008 NORDICOM’s activities are based on broad and extensive network of contacts and collaboration with members of the research community, media companies, politicians, regulators, teachers, librarians, and so forth, around the world. The activities at Nordicom are characterized by three main working areas. Media and Communication Research Findings in the Nordic Countries Nordicom publishes a Nordic journal, Nordicom Information, and an English language journal, Nordicom Review (refereed), as well as anthologies and other reports in both Nordic and English langu- ages. Different research databases concerning, among other things, scientific literature and ongoing research are updated continuously and are available on the Internet. Nordicom has the character of a hub of Nordic cooperation in media research. Making Nordic research in the field of mass communication and media studies known to colleagues and others outside the region, and weaving and supporting networks of collaboration between the Nordic research communities and colleagues abroad are two prime facets of the Nordicom work. The documentation services are based on work performed in national documentation centres at- tached to the universities in Aarhus, Denmark; Tampere, Finland; Reykjavik, Iceland; Bergen, Norway; and Göteborg, Sweden. Trends and Developments in the Media Sectors in the Nordic Countries Nordicom compiles and collates media statistics for the whole of the Nordic region. The statistics, to- gether with qualified analyses, are published in the series, Nordic Media Trends, and on the homepage. -

Participants List for Does Size Matter?

Participants list for Does size matter? - Universities competing in a global market/Liste des participants pour Est-ce que la taille importe ? La compétition universitaire dans un marché mondialisé. Reykjavik, Iceland 4/6/2008 - 6/6/2008 Jarle AARBAKKE Rector University of Tromsoe Norway Lena ADAMSON Principal secretary The Swedish National Agency for Higher Education Sweden Charlotte ALLER Senior Adviser Copenhagen Business School Denmark Ellen ALMGREN Project Manager Department of Statistics and Analysis Swedish National Agency for Higher Education Sweden Yvonne ANDERSSON Faculty Director Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Sweden Lena ANDERSSON-EKLUND Pro-Vice-Chancellor Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Sweden Dagny Osk ARADOTTIR University of Iceland Iceland Marcis AUZINSH Rector University of Latvia Latvia Magnus BALDURSSON Assistant to the Rector - Rector's Office The University of Iceland Iceland Jón Atli BENEDIKTSSON Rector's Office University of Iceland Iceland 1 Göran BEXELL Vice-Chancellor Lund University Sweden Jens BIGUM Chairman University of Aarhus Denmark Susanne BJERREGAARD Sectretary General Universities Denmark Denmark Thomas BOLAND Chief Executive Higher Education Authority Ireland Poul BONDE International Secretariat Aarhus Universitet Denmark Mikkel BUCHTER Special Adviser - Art and Education Ministry of Culture Denmark Steve CANNON University Secretary – Secretary’s Office University of Aberdeen United Kingdom Oon Ying CHIN Counsellor for Education Australian Department of Education, Employment -

Download the Conference Programme

UN photo Putting the Responsibility to Protect at the Centre of Europe October 13-14, 2016 University of Leeds Conference Programme Putting the Responsibility to Protect at the Centre of Europe Conference Programme Day 1, Thursday 13 October Venue: Great Woodhouse Room, University House 10.15 Welcome: Jason Ralph, Head of the School of Politics and International Studies (POLIS), University of Leeds. 10.30 Opening Plenary: The global state of R2P Chair: Jason Ralph, University of Leeds • Simon Adams, Director of the Global Center for R2P • Gillian Kitley, Senior Officer, United Nations Office for the Prevention of Genocide and the R2P • Phil Orchard, University of Queensland and Research Director of the Asia Pacific Centre for R2P (via Skype) • Adrian Gallagher, POLIS, University of Leeds 12.30 - 13.30 Buffet lunch 13.30 - 15.00 Plenary Roundtable 1: European Perspectives of R2P Chair: Edward Newman, University of Leeds • Jennifer Welsh, European University Institute, former UN Special Adviser on the R2P (via Skype) • Cristina Stefan, POLIS, University of Leeds • Chiara De Franco, University of Southern Denmark • Enzo Maria Le Fevre Cervini, Director of Research and Cooperation of the Budapest Centre for the International Prevention of Genocide and Mass Atrocities • Fabien Terpan, College of Europe, Sciences Po Grenoble 15.00 - 15.30 Coffee 15.30 - 16.30 Plenary Roundtable 2: European Perspectives of R2P Chair: Eamon Aloyo, Hague Institute • Christoph Meyer, King’s College London • Vasilka Sancin, Faculty of Law, University of Ljubljana -

New Publications from NORDICOM

10.1515/nor-2017-0407 Nordicom Review 38 (2017) 1, pp. 137 New Publications from NORDICOM The Assault on Gendering War and Journalism Peace Reporting Building knowledge to protect Some insights – some missing freedcom of expression links Ulla Carlsson & Reeta Pö- Berit von der Lippe & Rune yhteri (eds.) Nordicom 2017, Ottosen (eds.) Nordicom 2016, 378 p. 278 p. In connection with World Press War reporting has tradition- Freedom Day 2016 in Helsinki ally been a male activity. Elite an international conference, sources like politicians, high entitled Safety of Journalists. ranking military officers and state officials are collec- Knowledge is the Key, was arranged by UNESCO and tively still dominated by men, and it will take more than the UNESCO Chair on Freedom of Expression at the the presence of an increased number of female journal- University of Gothenburg in collaboration with IAM- ists to change this male hegemony. CR), and a range of other partners. There is, though, no deterministic link between The aim of the publication is to highlight and fuel sex/gender and more peaceful news or a more peaceful journalist safety as a field of research, as well as to in- world. spire further dialogues and new research initiatives. The This book offers analytic approaches to how traditio- contributions represent diverse perspectives on both em- nal war journalism is gendered. Through different case pirical and theoretical research and offer many quantita- studies, the book reveals how the framing of different tively and qualitatively informed insights. femininities and masculinities affects the reporting and our understanding of war and conflicts. -

A3ES, 97 Aalborg University, Ix, 151 Academic Careers (Women And) Career Progression, 3–22, 80, 116, 118, 120, 139–40, 153

Index A3ES, 97 social capital and, 5, 9, 142, 159, Aalborg University, ix, 151 184–7 academic careers (women and) sponsors, 5, 170, 174, 176, 182, career progression, 3–22, 80, 116, 184, 188, 191–2 118, 120, 139–40, 153, 173, traditional career path, 3, 13, 144, 177, 181, 186, 192 175, 180, 187, 189–90 casualised workforce, 86, 131–4, 171 Acar, F., 132, 153, 160 class and, 5, 9, 12–14, 23–7, 40, Acker, S., 15, 16, 63 46–52, 67, 89, 105–8, 117, 133, Acker, S. and Armenti, S., 7, 16, 147, 160, 169, 175–85, 188, 185, 192 191–2 Acker, S. and Feuerverger, G., cultural capital and, 5, 28, 31, 174, 192 141–2, 159, 181–2 Ackers, L., 146, 160, 180, 190, 192 entitlement, 8, 26, 30, 34, 38, 176–80, 192 Adelaide, 74, 77, 113 Adesina, J., 133, 161 family influence on, 5, 15, 23–5, 43, Akmut, Prof, 151 46–51, 66–7, 74, 80, 83–5, 97, Alvesson, M. and Sköldberg, K., 103–6, 128, 130–1, 141, 146–8, 127, 161 153–4, 159–60, 175–80 Alvesson, M. and Sveningsson, S., 37, feminist academics, 3–5, 8, 14–15, 43 27, 32, 41–3, 54–5, 70–3, 76, Amâncio, L., 97, 100 79–80, 107, 117, 127, 133, 139, Amaral, A., 94–5, 97–8 143, 158, 173–6, 190–1 Ankara, 149–50, 186 future challenges, 188–90 Ankara University, 149–53, gender identity, 9, 30, 54, 87–92, 186 106–9, 182, 187–8 Ashall, S., 179, 185, 192 generational change, 3–6, 79, 83, Asmar, C., 10, 16 128, 154, 159–60, 168–95 Association of Social Science influence of matriarchies on, 46–50, Researchers, 80 70–3, 106, 176 ATGender, 55 life-course and, 5, 9, 12 –15, 189 Aturtuk, M.K., 148 mobility, 5, 146, 151–2, 156, 180–1, Australasian Evaluation Society, 80 191–2 Australia, 7, 10, 39, 106, 112–13, 115, organisational culture, 5, 7–9, 172–5 128, 157 outsiders, 5, 27, 51, 53, 105–9, 178–80 Babbie, E., Mouton, J., Payze, C., playing the ‘game’ (or not), 5, 30–5, Vorster, J.