Nuclear Weapons Materials Gone Missing: What Does History Teach?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adolf Eichmann in Buenos Aires

CAPTURING THE DEVIL The real story of the capture of Adolph Eichmann Based on the memoirs of Peter Zvi Malkin A feature film written and directed by Philippe Azoulay PITCH Peter Zvi Malkin, one of the best Israeli agents, is volunteering to be part of the commando set up to capture Adolf Eichmann in Buenos Aires. As the others, he wants to take revenge for the killing of his family, but the mission is to bring Eichmann alive so that he may be put on trial in Jerusalem. As Peter comes to consider his prisoner an ordinary and banal being he wants to understand the incomprehensible. To do so, he disobeys orders. During the confrontation between the soldier and his prisoner, a strange relationship develops… CAPTURING THE DEVIL HISTORICAL CONTEXT 1945 The Nuremberg trial is intended to clear the way to for the rebuilding of Western Europe Several Nazi hierarchs have managed to hide or escape Europe 1945 Adolph Eichmann who has organized the deportations and killings of millions of people is hiding in Europe. 1950 Eichmann is briefly detained in Germany but escapes to South America thanks to a Red Cross passport. In Europe and in Israel, Jews who survived the camps try to move into a new life. The young state of Israel fights for its survival throughout two wars in 1948 and 1956. The Nazi hunt is considered a “private“ matter. 1957 the Bavarian General Attorney Fritz Bauer, who has engaged into a second denazification of Germany’s elite, gets confirmation that Eichmann may be located in Argentina. -

The Truth of the Capture of Adolf Eichmann (Pdf)

6/28/2020 The Truth of the Capture of Adolf Eichmann » Mosaic THE TRUTH OF THE CAPTURE OF ADOLF EICHMANN https://mosaicmagazine.com/essay/history-ideas/2020/06/the-truth-of-the-capture-of-adolf-eichmann/ Sixty years ago, the infamous Nazi official was abducted in Argentina and brought to Israel. What really happened, what did Hollywood make up, and why? June 1, 2020 | Martin Kramer About the author: Martin Kramer teaches Middle Eastern history and served as founding president at Shalem College in Jerusalem, and is the Koret distinguished fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Listen to this essay: Adolf Eichmann’s Argentinian ID, under the alias Ricardo Klement, found on him the night of his abduction. Yad Vashem. THE MOSAIC MONTHLY ESSAY • EPISODE 2 June: The Truth of the Capture of Adolf Eichmann 1x 00:00|60:58 Sixty years ago last month, on the evening of May 23, 1960, the Israeli prime minister David Ben-Gurion made a brief but dramatic announcement to a hastily-summoned session of the Knesset in Jerusalem: A short time ago, Israeli security services found one of the greatest of the Nazi war criminals, Adolf Eichmann, who was responsible, together with the Nazi leaders, for what they called “the final solution” of the Jewish question, that is, the extermination of six million of the Jews of Europe. Eichmann is already under arrest in Israel and will shortly be placed on trial in Israel under the terms of the law for the trial of Nazis and their collaborators. In the cabinet meeting immediately preceding this announcement, Ben-Gurion’s ministers had expressed their astonishment and curiosity. -

170814 the House on Garibaldi Street

The House on Garibaldi Street by Isser Harel, 1912-2003 Published: 1975 J J J J J I I I I I Table of Contents Introduction by Shlomo J. Shpiro, 1997 Dramatis Personae & Chapter 1 … thru … Chapter 30 Index J J J J J I I I I I Introduction by Shlomo J. Shpiro THE PUBLIC trial in Israel of Adolf Eichmann, the man who directed the Third Reich’s ‘Final Solution’, was held in 1961 under an unprecedented publicity coverage. The trial, which took place in Jerusalem, attracted hundreds of reporters and media crews from all over the world. For the first time since the end of the Second World War the horrific crimes of the Nazi regime against the Jewish people were exposed in all their brutality by one of their leading perpetrators. Eichmann stood at the top of the Gestapo pyramid dedicated to the destruction of Europe’s Jewry, and was personally responsible not only for policy decisions but for the everyday running of this unparalleled genocide. His trial and subsequent execution brought to millions of homes around the world the untold story of the Holocaust from its chief administrator. (I-1) The Eichmann trial had a profound influence in particular on the young generation of Israeli citizens, born after the end of the Second World War. This generation, born into a country which had built itself as a national home for the Jewish people in order to prevent such persecution in the future, swore as it joined the army ‘never again’ to let Jewish people be led to their death unresisting. -

Operation Finale’ Eichmann Is Subpar

CHICAGOLAWBULLETIN.COM FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 7, 2018 ® Volume 164, No. 175 Serving Chicago’s legal community for 163 years K i n g s l e y. I t’s not that his performance as ‘Operation Finale’ Eichmann is subpar. As one ex- pects, Kingsley is exemplary. I t’s that through Kingsley Eich- mann is presented as a dignified, spy thriller has a Ben RE B E C CA dedicated family man, proud of L. FORD his contribution to the war effort —not majestic, but certainly m a g i s t e r i a l . Kingsley problem Rebecca L. Ford is counsel to Scharf A one-dimensional portrayal Banks Marmor LLC, and concentrates her that set up Eichmann as a straw practice on complex litigation, compliance, villain without providing insight board governance and specialized War criminal written as dynamic character; employment issues. She is the former into his perspective would have executive vice president for litigation and killed the film dramatically. film exchanges accuracy for heroism, drama intellectual property at MGM. She can be But with Kingsley in the role, reached at [email protected]. Eichmann is portrayed as a sly fox, a verbal fencer, a worthy op- annah Arendt, the mid- by Chris Weitz (“Rogue One: A ponent in a cat-and-mouse game century philosopher Star Wars Story”), based on Eich- Isaac, who resembles a young with his Mossad interrogators. and Holocaust refugee, m a n n’s May 1960 capture by Is- Omar Sharif, has become a go-to According to Arendt’s now-fa- conceived her theory of raeli intelligence agents. -

David Rittberg Wins JFN's 2019 JJ Greenberg Memorial Award Spring

March 29-April 4, 2019 Published by the Jewish Federation of Greater Binghamton Volume XLVIII, Number 13 BINGHAMTON, NEW YORK Spring CJS program on “Rethinking ‘the Ghetto’ in Jewish History and Beyond” The spring 2019 program of the College ly-Modern Italian Ghettos.” Francesconi is will be on Thursday, May 16. Gina Glasman Several of his paintings depicted late 18th cen- of Jewish Studies will focus on different assistant professor of history and director will speak on “Painting a Ghetto Paradise: tury Jewish ghettos in an idealized fashion. aspects of “the ghetto” as an historically of the program of Judaic studies at the The Political Artistry of Moritz Daniel Op- College of Jewish Studies programs specific and sometimes idealized place in University at Albany. Her research and penheim.” Glasman is a lecturer in Hebrew are open to the entire community; general Jewish history and as an abstract concept publications address the social, religious and and Yiddish literature in the Judaic studies admission is $8 per program, or $20 for that has relevance beyond Jewish history. cultural aspects of the early modern history department at Binghamton University. She all three programs; senior admission is $5 The first lecture in the program will be of Jews in Italy, focusing on the multifac- will talk about Moritz Daniel Oppenheim, per program or $12 for all three programs. on Thursday, May 2, “Ghetto: Invention eted politics and dynamics of ghetto life. known as the first Jewish painter of the BU students are welcome to attend with of a Place, History of an Idea.” Mitchell She is currently completing a monograph, modern era. -

Az Izraeli Nemzetbiztonsági Rendszer Fejlődésének Története

NEMZETBIZTONSÁGI SZEMLE 7. évfolyam (2019) 4. szám 3–19. • doi: 10.32561/nsz.2019.4.1 Rémai Dániel1 Az izraeli nemzetbiztonsági rendszer fejlődésének története Evolution of the Israeli Intelligence Community A Közel-Kelet országai komplex, bonyolult világot alkotnak, amelyben sajátos szabá- lyok uralkodnak. A 20. század történelmét végigkíséri az arab–izraeli ellentét, amely számos alkalommal vezetett nyílt fegyveres konfliktusokhoz. A komplex biztonsági helyzet folyamatos változása a titkosszolgálati szervek számára is számos alkalom- mal okozott nem várt kihívásokat az államalapítást követő évtizedekben. A tanulmány az egyes korszakok biztonsági kihívásainak fényében próbálja meg felvázolni az izraeli titkosszolgálati közösség szervezeteinek fejlődését, a feladatkörök változását. Külön hangsúlyt fektet az 1990 utáni időszakra, amely során kialakult az a status quo, amely meghatározza napjaink izraeli hírszerző közösségét. Tekintettel arra, hogy az elmúlt évtizedek legjelentősebb globális biztonsági kihívása a terrorizmus volt, a tanulmány részletesen vizsgálja a Shin Bet, az izraeli belbiztonsági szolgálat működését, a fel- merülő kihívásokat és az ezekre adott válaszokat. Kulcsszavak: Izrael, terrorizmus, hírszerző közösség, nemzetbiztonsági rendszer, törté- nelmi fejlődés The countries of the Middle East are a complex world with specific rules. The Arab– Israeli conflict was present all throughout the history of the 20th century, developing into open armed conflict on many occasions. The constant change of the complex security situation posed unexpected challenges for the intelligence services since the foundation of the State of Israel. The study outlines the evolution of the organisations of the Israeli intelligence community in the light of the constantly changing threats. The study focuses on the post-1990 period, because the status quo that defines today’s Israeli intelligence community was formed at this time. -

Longevity Industry in Israel LANDSCAPE OVERVIEW

Longevity Industry in Israel LANDSCAPE OVERVIEW SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGIES, COMPANIES, INVESTORS, TRENDS Longevity Industry in Israel Landscape Overview 2018 Mind Map Longevity Industry in Israel 3 Executive Summary 6 Chapter I: Israel Longevity Industry Landscape Overview 18 Сhapter II: History of Geroscience in Israel 37 Chapter III: Current State of Longevity in Israel 42 Chapter IV: Israeli Longevity Alliance (ISRLA)/VETEK 58 Chapter V: Top Universities Focusing on Longevity 61 Chapter VI: Media and Conferences 70 Chapter VII: The Policy Landscape of Longevity in Israel 76 Chapter VIII: Global Landscape Overviews from our previous reports 84 Chapter IX: The Economics of Longevity in Israel 109 APPENDIX/ PROFILES 10 Israel Longevity R&D Centers 128 10 Israel Longevity Non-Profit Organizations 141 10 Israel Longevity Conferences 154 60 Israel Longevity Influencers 167 160 Companies: Longevity in Israel 230 180 Investors: Longevity in Israel 393 Disclaimer 577 Longevity Companies - 160 Industry in Israel Personalized Investors - 180 Medicine Non-Profits - 10 Landscape 2019 R&D Centers - 10 Progressive Wellness Investors Companies Non-Profits R&D Centers Preventive Medicine AgeTech LONGEVITY Regenerative INTERNATIONAL Medicine Longevity Industry in Israel 2019 - 160 COMPANIES Drug Development Progressive wellness Gene therapies AgeTech Neurotech Others Progressive R&D Implant & Prosthetics Cell therapy Diagnostic Executive Summary Executive Summary 6 BIRAX Aging: Leapfrogging Population Ageing & Establishing A Strong Longevity Industry & R&D Landscape One of the most significant developments to occur in the Israel Longevity Industry in the past year is the formation of the BIRAX Partnership on Aging. The Britain Israel Research and Academic Exchange Partnership (BIRAX) is a multi-million pound initiative launched by the British Council, the Pears Foundation and the British Embassy in Israel, supported by both the Israeli and British Ministries of Science, to invest in research initiatives jointly undertaken by scientists in Britain and Israel. -

Review of the Year

Review of the Year UNITED STATES United States National Affairs A OR THE JEWISH COMMUNITY—as for the entire nation—1998 was the year of the Monica Lewinsky scandal, a black hole that swallowed up media attention and the time and energies of countless government officials and com- mentators. The diversion created by the scandal notwithstanding, the year was filled with issues and events of considerable importance to the Jewish commu- nity. Congressional elections were held in 1998. It was also a year in which the House of Representatives voted down a proposed constitutional amendment that would have had profound implications for religious liberty, as well as a year in which the constitutionality of vouchers was addressed by the highest American court ever to consider the issue. It was a year, too, of profound developments in Catholic-Jewish relations, including the release by the Vatican of its historic state- ment on the Holocaust, and a year in which the U.S. Supreme Court declined to find that the American Jewish community's leading voice on American-Israeli re- lations was obligated to register as a "political action committee" (but left the issue open for further consideration). Finally, 1998 was the year when it appeared that John Demjanjuk, at one time sentenced to death as a war criminal and still viewed as such by many in the Jewish community, might well be allowed to live out his remaining years as an American citizen. THE POLITICAL ARENA Congressional Elections As election year 1998 progressed, it was difficult to discern any overriding theme. -

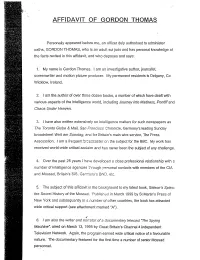

Affidavit Of·Gordon Thomas

AFFIDAVIT OF· GORDON THOMAS Personally appeared before me, an officer duly authorised to administer oaths, GORDON THOMAS, who is an adult sui juris and has personal knowledge of the facts recited in this affidavit, and who deposes and says: 1. My name is Gordon Thomas. I am an investigative author, joumalist, screenwriter and motion picture producer. My permanent residents is Delgany, Co Wicklow, Ireland. 2. I am the author of over three dozen books, a number of which have dealt with various aspects of the intelligence world, including Journey into Madness, Pontiff and Chaos Under Heaven. 3. I have also written extensively on intelligence matters for such newspapers as The Toronto Globe & Mail, San Francisco Chronicle, Germany's leading Sunday broadsheet Welt am Sonntag, and for Britain's main wire service, The Press Association. I am a frequent breadcaster on the subject for the BBC. My work has received world-wide critical acclaim and has never been the subject of any challenge. 4. Over the past 25 years I have developed a close professional relationship with a number of intelligence agencies :hrough f)ersonal contacts with members of the CIA and Mossad, Britain's SIS, Ge,:;-:eny's BND, etc. 5. The subject of this affidavit is the background to my latest book, Gideon's Spies: the Secret History of the Mossed. Published in March 1999 by St Martin's Press of New York and subsequently in e number of other countries, the book has attracted wide critical support (see attachment marked "A"). , 6. I am also the writer and narrator of a documentary telecast "The Spying Machine", aired on March 13, 1998 by Great Britain's Channel 4 Independent Television Network. -

The Jonathan Jay Pollard Espionage Case: a Damage Assessment ~

MORI DociD: 1346933 .. · ,. I Key to Exemptions 1. Executive Order 13526 section 3.3 (b)(l) 2. Executive Order 13526 section 3.3 (b)(6) 3. Central Intelligence Agency Act of 1949 (50 U.S.C., section 403g) 4. 5 U.S.C. section 522 (b)(3), the Freedom oflnformation Act 5. 5 U.S.C. section 522 (b)(6) 6. 5 U.S.C. section 522 (b)(7)(C) 7. 5 U.S.C. section 522 (b)(7)(E) DECLASSIFIED UNDER AUTHORITY OF THE INTERAGENCY SECURITY CLASSIFICATION APPEALS PANEL. E.O. 13526, SECTION 5.3(b)(3) ISCAP No. L b t11- 0 \ ~ , document j__ I I i . i. I I I I I . i --! MORI DociD: 1346933 :-: T13P SSSPET I I 1 II DIRECTOR OF CENTRAL INTELLIGENCE Foreign Denial and Deception Analysis Committee 30 October 1987 f THE JONATHAN JAY POLLARD ESPIONAGE CASE: A DAMAGE ASSESSMENT ~ Study Director, j L_--~----~------------~----~ AND ~I MORI DociD: 1346933 Jj Preface This study, the Foreign Denial and Deception of the. Director of of two assessments of damage a result of Jonathan Pollard's espionage on behalf of 1984-85, which are being issued almost simultaneously. The other is an assessment prepared for the Department of Defense by the Office of Naval Intelligence and the · Naval Investiqative Service, Naval Security and Investigative · Command, where Pollard was employed during his espionage career. The principal drafters consulted closely during preparation of the two studies. Although they differ somewhat in detail and emphasis, there is mutual agreement concerning their findings. ~ · ~ . The Study Director gratefully acknowledges the valu&Ple assistance of contributors from throughout the Intelligence Community to the project. -

·Nuclear Cops Jail1;400 in Sit-In at Seabrook Reactor Site

MAY 13, 1977 . 35 CENTS VOLUME 41/NUMBER 18 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE_ WORKING PEOPLE ·nuclear Cops jail1;400 in sit-in at Seabrook reactor site . -PAGE17 Intercontinental Press/Fred Murphy · -PAGE 3 Student demonstrations PUertO RICO's · face halt in rent hikes luture debated Juan Mari Bras presents case for independence -· PAGE 21 In Brief DROWNING IN THE SECRETARIAL POOL: Several mob. In violation of Louisiana state law, Tyler-a juvenile THIS hundred clerical workers marked National Office Workers was sentenced to life imprisonment at Angola penitentiary. Day in New York with a noon rally April 27. National His mother, Juanita Tyler, is asking that protest letters be WEEK'S Secretaries Week was first proclaimed in 1952. According to sent urging the U.S. Supreme Court to hear an appeal on the Washington Post, it was an occasion for secretaries to this unconstitutional act. Write to the Clerk of Court, U.S. let. the "'business world know how proud they are of their Supreme Court, Washington, D.C., with copies to the Gary MILITANT profession, and the diversified opportunities it has given Tyler Defense Fund, Post Office Box 52223, New Orleans, 4 Steel-plant sales them for exciting, stimulating and challenging careers." Louisiana 70152. Juanita Tyler also says this is the address top 4,000 The militant New York crowd, however, protested sex of the only committee authorized to receive donations for 7 Feminists protest discrimination and told bosses to quit treating secretaries her son's defense. red-baiting like personal maids. The event, organized by Women Office Workers, included a contest on "ridiculous personal er SPY SCANDAL AT UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVA 8 Racists OK busing rands." One entry said she was expected to fill in the tough NIA: A Penn Committee to End Campus Spying has been whites words in her boss's unfinished crossword puzzles. -

Dimona (Shhh! It's a Secret)

Published by Americans for The Link Middle East Understanding, Inc. Volume 46, Issue 3 Link Archives: www.ameu.org July-August, 2013 D i m o n a (Shhh! It’s a secret.) By John F. Mahoney The Link Page 2 AMEU Board of Directors Israel is today’ssixth, if not fifth, most powerful nuclear state, Jane Adas (Vice President) with 100-plus nuclear weapons, along with the ability to build Elizabeth D. Barlow atomic, neutron and hydrogen bombs. How did it happen? Edward Dillon Rod Driver John Goelet Back in the late 1950s, France built a nuclear reactor for the Is- David Grimland raelis at a site in the Negev desert called Dimona. Ostensibly in- Richard Hobson (Treasurer) tended for generating nuclear energy for domestic use, it was later Anne R. Joyce revealed that its cooling circuits were built two to three times lar- Hon. Robert V. Keeley ger than necessary for the supposed 26-megawatt reactor, proof Kendall Landis that, from the beginning, it was designed to be a plutonium ex- Robert L. Norberg (President) traction plant for nuclear weapon fuel. Francis Perrin, the high Hon. Edward L. Peck commissioner of the French Atomic Energy Agency from 1951 to Donald L. Snook 1970, later explained why France gave atomic secrets to the fledg- Rosmarie Sunderland ing Jewish state: “Wethought the Israeli bomb was aimed against James M. Wall the Americans, not to launch it against America but to say ‘if you don’twant to help us in a critical situation we will require you to AMEU National help us, otherwise we will use our nuclear bombs’.”1 Council Hugh D.