Feminisms and Feminist Identity in Women's Flat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

Recognised English and UK Ngbs

MASTER LIST – updated August 2014 Sporting Activities and Governing Bodies Recognised by the Sports Councils Notes: 1. Sporting activities with integrated disability in red 2. Sporting activities with no governing body in blue ACTIVITY DISCIPLINES NORTHERN IRELAND SCOTLAND ENGLAND WALES UK/GB AIKIDO Northern Ireland Aikido Association British Aikido Board British Aikido Board British Aikido Board British Aikido Board AIR SPORTS Flying Ulster Flying Club Royal Aero Club of the UK Royal Aero Club of the UK Royal Aero Club of the UK Royal Aero Club of the UK Aerobatic flying British Aerobatic Association British Aerobatic Association British Aerobatic Association British Aerobatic Association British Aerobatic Association Royal Aero Club of UK Aero model Flying NI Association of Aeromodellers Scottish Aeromodelling Association British Model Flying Association British Model Flying Association British Model Flying Association Ballooning British Balloon and Airship Club British Balloon and Airship Club British Balloon and Airship Club British Balloon and Airship Club Gliding Ulster Gliding Club British Gliding Association British Gliding Association British Gliding Association British Gliding Association Hang/ Ulster Hang Gliding and Paragliding Club British Hang Gliding and Paragliding Association British Hang Gliding and Paragliding Association British Hang Gliding and Paragliding Association British Hang Gliding and Paragliding Association Paragliding Microlight British Microlight Aircraft Association British Microlight Aircraft Association -

The Literacy Practices of Feminist Consciousness- Raising: an Argument for Remembering and Recitation

LEUSCHEN, KATHLEEN T., Ph.D. The Literacy Practices of Feminist Consciousness- Raising: An Argument for Remembering and Recitation. (2016) Directed by Dr. Nancy Myers. 169 pp. Protesting the 1968 Miss America Pageant in Atlantic City, NJ, second-wave feminists targeted racism, militarism, excessive consumerism, and sexism. Yet nearly fifty years after this protest, popular memory recalls these activists as bra-burners— employing a widespread, derogatory image of feminist activists as trivial and laughably misguided. Contemporary academics, too, have critiqued second-wave feminism as a largely white, middle-class, and essentialist movement, dismissing second-wave practices in favor of more recent, more “progressive” waves of feminism. Following recent rhetorical scholarly investigations into public acts of remembering and forgetting, my dissertation project contests the derogatory characterizations of second-wave feminist activism. I use archival research on consciousness-raising groups to challenge the pejorative representations of these activists within academic and popular memory, and ultimately, to critique telic narratives of feminist progress. In my dissertation, I analyze a rich collection of archival documents— promotional materials, consciousness-raising guidelines, photographs, newsletters, and reflective essays—to demonstrate that consciousness-raising groups were collectives of women engaging in literacy practices—reading, writing, speaking, and listening—to make personal and political material and discursive change, between and across differences among women. As I demonstrate, consciousness-raising, the central practice of second-wave feminism across the 1960s and 1970s, developed out of a collective rhetorical theory that not only linked personal identity to political discourses, but also 1 linked the emotional to the rational in the production of knowledge. -

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

Batman: Bloom Vol 9 Free Ebook

FREEBATMAN: BLOOM VOL 9 EBOOK Greg Capullo,Scott Snyder | 200 pages | 27 Dec 2016 | DC Comics | 9781401269227 | English | United States BATMAN VOL. 9: BLOOM As the new Batman, former police commissioner Jim Gordon is in for the fight of his life against the bizarre threat of Mr. Bloom, who controls the underworld in Gotham City! At the same time, an amnesiac Bruce Wayne has discovered the truth of his past as the Dark Knight—and now, he must descend into the Batcave and reclaim that painful legacy. Bloom and his minions? The penultimate chapter to Scott Snyder and Greg Capullo's epic #1 NEW YORK TIMES bestselling series is here in BATMAN VOL. 9. has been visited by 1M+ users in the past month. Batman: Bloom (Collected) Bloom and his minions? The penultimate chapter to Scott Snyder and Greg Capullo's epic #1 NEW YORK TIMES bestselling series is here in BATMAN VOL. 9. Buy Batman TP Vol 9 Bloom 01 by Snyder, Scott, Capullo, Greg (ISBN: ) from Amazon's Book Store. Everyday low prices and free delivery on. Issues Batman (Volume 2)#46, Batman (Volume 2)#47, Batman (Volume 2)#48, Batman Batman: Bloom. Cover Batman September, Rated T for Teen (12+) ISBN. Batman Vol. 9: Bloom (the New 52) Buy Batman TP Vol 9 Bloom 01 by Snyder, Scott, Capullo, Greg (ISBN: ) from Amazon's Book Store. Everyday low prices and free delivery on. Batman Vol. 9: Bloom (The New 52): Snyder, Scott, Capullo, Greg: Books - Download at: ?book= Batman Vol. 9: Bloom (The New 52) pdf download. -

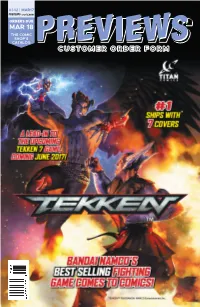

MAR17 World.Com PREVIEWS

#342 | MAR17 PREVIEWS world.com ORDERS DUE MAR 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Mar17 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 2/9/2017 1:36:31 PM Mar17 C2 DH - Buffy.indd 1 2/8/2017 4:27:55 PM REGRESSION #1 PREDATOR: IMAGE COMICS HUNTERS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS BUG! THE ADVENTURES OF FORAGER #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT/ YOUNG ANIMAL JOE GOLEM: YOUNGBLOOD #1 OCCULT DETECTIVE— IMAGE COMICS THE OUTER DARK #1 DARK HORSE IDW’S FUNKO UNIVERSE MONTH EVENT IDW ENTERTAINMENT ALL-NEW GUARDIANS TITANS #11 OF THE GALAXY #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT MARVEL COMICS Mar17 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 2/9/2017 9:13:17 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Hero Cats: Midnight Over Steller City Volume 2 #1 G ACTION LAB ENTERTAINMENT Stargate Universe: Back To Destiny #1 G AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Casper the Friendly Ghost #1 G AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Providence Act 2 Limited HC G AVATAR PRESS INC Victor LaValle’s Destroyer #1 G BOOM! STUDIOS Misfi t City #1 G BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Swordquest #0 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT James Bond: Service Special G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Spill Zone Volume 1 HC G :01 FIRST SECOND Catalyst Prime: Noble #1 G LION FORGE The Damned #1 G ONI PRESS INC. 1 Keyser Soze: Scorched Earth #1 G RED 5 COMICS Tekken #1 G TITAN COMICS Little Nightmares #1 G TITAN COMICS Disney Descendants Manga Volume 1 GN G TOKYOPOP Dragon Ball Super Volume 1 GN G VIZ MEDIA LLC BOOKS Line of Beauty: The Art of Wendy Pini HC G ART BOOKS Planet of the Apes: The Original Topps Trading Cards HC G COLLECTING AND COLLECTIBLES -

Roller Derby: Past, Present, Future RESEARCH PAPER for ASU’S Global Sport Institute

Devoney Looser, Foundation Professor of English Department of English, Arizona State University Tempe, AZ 85287-1401 [email protected] Roller Derby: Past, Present, Future RESEARCH PAPER for ASU’s Global Sport Institute SUMMARY Is roller derby a sport? Okay, sure, but, “Is it a legitimate sport?” No matter how you’re disposed to answer these questions, chances are that you’re asking without a firm grasp of roller derby’s past or present. Knowledge of both is crucial to understanding, or predicting, what derby’s future might look like in Sport 2036. From its official origins in Chicago in 1935, to its rebirth in Austin, TX in 2001, roller derby has been an outlier sport in ways admirable and not. It has long been ahead of the curve on diversity and inclusivity, a little-known fact. Even players and fans who are diehard devotees—who live and breathe by derby—have little knowledge of how the sport began, how it was different, or why knowing all of that might matter. In this paper, which is part of a book-in-progress, I offer a sense of the following: 1) why roller derby’s past and present, especially its unusual origins, its envelope-pushing play and players, and its waxing and waning popularity, matters to its future; 2) how roller derby’s cultural reputation (which grew out of roller skating’s reputation) has had an impact on its status as an American sport; 3) how roller derby’s economic history, from family business to skater-owned-and- operated non-profits, has shaped opportunity and growth; and 4) why the sport’s past, present, and future inclusivity, diversity, and counter-cultural aspects resonate so deeply with those who play and watch. -

Wedlock Or Deadlock? : Feminists' Attemps to Engage Irrigation

Wedlock or deadlock? Feminists’ attempts to engage irrigation engineers Promotor: Prof. Linden F. Vincent, hoogleraar in Irrigatie en waterbouwkunde Wageningen Universiteit Samenstelling promotiecommissie: Prof. Dr. Patricia Howards, Wageningen Universiteit Prof. Dr. Pieter van der Zaag, IHE-UNESCO, Delft Prof. Dr. Cecile Jackson, University of East-Anglia, Norwich, UK Dr. Loes Schenk-Sandbergen, Universiteit van Amsterdam Dit onderzoek is uitgevoerd binnen de onderzoeksschool CERES Wedlock or deadlock? Feminists’ attempts to engage irrigation engineers Margreet Z. Zwarteveen Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor op gezag van de rector magnificus van Wageningen Universiteit, Prof. Dr. M. J. Kropff, in het openbaar te verdedigen op dinsdag 6 juni 2006 des namiddags te vier uur in de Aula WEDLOCK OR DEADLOCK? FEMINISTS’ ATTEMPTS TO ENGAGE IRRIGATION ENGINEERS. Wageningen UR. Promotor: Vincent, L.F. Wageningen: Margreet Z. Zwarteveen, 2006. – p. 304. ISBN: 90-8504-398-0 Copyright © 2006, by Margreet Z. Zwarteveen, The Netherlands Contents Tables and figures ............................................................................................................9 Acronyms..........................................................................................................................10 Glossary............................................................................................................................11 Acknowledgments..........................................................................................................13 -

“Why So Serious?” Comics, Film and Politics, Or the Comic Book Film As the Answer to the Question of Identity and Narrative in a Post-9/11 World

ABSTRACT “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD by Kyle Andrew Moody This thesis analyzes a trend in a subgenre of motion pictures that are designed to not only entertain, but also provide a message for the modern world after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The analysis provides a critical look at three different films as artifacts of post-9/11 culture, showing how the integration of certain elements made them allegorical works regarding the status of the United States in the aftermath of the attacks. Jean Baudrillard‟s postmodern theory of simulation and simulacra was utilized to provide a context for the films that tap into themes reflecting post-9/11 reality. The results were analyzed by critically examining the source material, with a cultural criticism emerging regarding the progression of this subgenre of motion pictures as meaningful work. “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Mass Communications Area by Kyle Andrew Moody Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2009 Advisor ___________________ Dr. Bruce Drushel Reader ___________________ Dr. Ronald Scott Reader ___________________ Dr. David Sholle TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... III CHAPTER ONE: COMIC BOOK MOVIES AND THE REAL WORLD ............................................. 1 PURPOSE OF STUDY ................................................................................................................................... -

Recommended Reading Superheroes

Recommended Reading Superheroes Superhero Picture Books Title Call No. AR Level Character(s) Buzz Boy and Fly Guy E Arn 1.3/0.5 Marvel The Avengers Storybook Collection E Ave Avengers The Avengers Reading Adventures E Ave Avengers Supergirl Takes Off E Car 1.9/0.5 Supergirl The Astonishing Secret of Awesome Man E Cha 3.4/0.5 Eliot Jones, Midnight Superhero E Cot 2.7/0.5 Battle at Avengers Tower E Dav Avengers Age of Ultron: Hulk to the Rescue E Dav 2.3/0.5 Avengers Wedgieman to the Rescue E Har 2.3/0.5 Spider-Man Versus the Vulture E Hil 2.4/0.5 Spiderman Ten Rules of Being a Superhero E Kna 1.9/0.5 Super Jumbo E Koe Game Over E Lam Ant-Man Mega Mission! E Lan 4.4/0.5 Power Bad Baby E Mac 1.7/0.5 The Story of Spider-Man E Mac 2.2/0.5 Spiderman The Story of the X-Men E Mac 2.4/0.5 X-Men These Are the X-Men E Mac 1.5/0.5 X-Men Avengers Save the Day E May Avengers Age of Ultron: Friends and Foes E Pal 3.2/0.5 Avengers Amazing Battles E Pee 4.4/0.5 Batman & Friends Ten Rules of Being a Superhero E Pil 1.9/0.5 Princess Super Kitty E Por 1.9/0.5 Superhero School E Rob Super Hair-o and the Barber of Doom E Roc 1.8/0.5 League Supertruck E Sav 1.5/0.5 Timothy and the Strong Pajamas E Sch 2.7/0.5 The Amazing Adventures of Bumblebee Boy E Som 2.4/0.5 Superman: I am Superman E Tei 2.7/0.5 Superman Batgirl Takes Off E Web Batgirl Super Guinea Pig to the Rescue E Wie 3.3/0.5 Superhero Joe and the Creature Next Door E Wei 2.3/0.5 Batman’s Hero Files E Wre 2.9/0.5 Batman Catch Catwoman! E Wre 0.9/0.5 Catwoman Updated September 2017 Recommended Reading Superheroes This is Ant-Man E Way 1.5/0.5 Ant-Man Superhero Chapter Books Title Call No. -

Teen Titans Changing of the Guard Free

FREE TEEN TITANS CHANGING OF THE GUARD PDF Sean McKeever | 192 pages | 25 Aug 2009 | DC Comics | 9781401223090 | English | New York, NY, United States Teen Titans () #69 - DC Entertainment Jump to navigation. Teen Titans Go! Now play as the youthful up-and-comers. The Teen Titans are all about proving themselves, and with this set you can save your best cards for when you really need them. The big new focus of the set revolves around Ongoing abilities: Cards that stay in play until you need them. Every time you put an Ongoing card into Teen Titans Changing of the Guard, it essentially gives you an extra card to utilize on a future turn. Previously, only Locations and a couple of other cards could ever stay in play. Now every card type at every power level has multiple different cards that are Ongoing. Sometimes they help you every turn. But mostly they stay in play until Teen Titans Changing of the Guard choose to discard them for their mighty effects. If you can build up several Ongoing cards, unleash as many as you need to take down the Super-Villains! This set also pays attention to the different card types you have in play. Playing cards from your hand puts cards into play as usual. But with Ongoing cards out there, you often have several card types in play already. Such synergy! Contents Summary:. Buy Now. Learn To Play. All Rights Reserved. Teen Titans: Changing of the Guard | DC Database | Fandom Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. -

Feminism & Philosophy Vol.5 No.1

APA Newsletters Volume 05, Number 1 Fall 2005 NEWSLETTER ON FEMINISM AND PHILOSOPHY FROM THE EDITOR, SALLY J. SCHOLZ NEWS FROM THE COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF WOMEN, ROSEMARIE TONG ARTICLES MARILYN FISCHER “Feminism and the Art of Interpretation: Or, Reading the First Wave to Think about the Second and Third Waves” JENNIFER PURVIS “A ‘Time’ for Change: Negotiating the Space of a Third Wave Political Moment” LAURIE CALHOUN “Feminism is a Humanism” LOUISE ANTONY “When is Philosophy Feminist?” ANN FERGUSON “Is Feminist Philosophy Still Philosophy?” OFELIA SCHUTTE “Feminist Ethics and Transnational Injustice: Two Methodological Suggestions” JEFFREY A. GAUTHIER “Feminism and Philosophy: Getting It and Getting It Right” SARA BEARDSWORTH “A French Feminism” © 2005 by The American Philosophical Association ISSN: 1067-9464 BOOK REVIEWS Robin Fiore and Hilde Lindemann Nelson: Recognition, Responsibility, and Rights: Feminist Ethics and Social Theory REVIEWED BY CHRISTINE M. KOGGEL Diana Tietjens Meyers: Being Yourself: Essays on Identity, Action, and Social Life REVIEWED BY CHERYL L. HUGHES Beth Kiyoko Jamieson: Real Choices: Feminism, Freedom, and the Limits of the Law REVIEWED BY ZAHRA MEGHANI Alan Soble: The Philosophy of Sex: Contemporary Readings REVIEWED BY KATHRYN J. NORLOCK Penny Florence: Sexed Universals in Contemporary Art REVIEWED BY TANYA M. LOUGHEAD CONTRIBUTORS ANNOUNCEMENTS APA NEWSLETTER ON Feminism and Philosophy Sally J. Scholz, Editor Fall 2005 Volume 05, Number 1 objective claims, Beardsworth demonstrates Kristeva’s ROM THE DITOR “maternal feminine” as “an experience that binds experience F E to experience” and refuses to be “turned into an abstraction.” Both reconfigure the ground of moral theory by highlighting the cultural bias or particularity encompassed in claims of Feminism, like philosophy, can be done in a variety of different objectivity or universality.