Vol.6 No.3 ISSN 2518-3966

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Interplay of Landscapes in the Guyanese Emigrant's Reality in Jan Lowe Shinebourne's the Godmother

Article Migratory Realities: The Interplay of Landscapes in the Guyanese Emigrant’s Reality in Jan Lowe Shinebourne’s The Godmother and Other Stories Abigail Persaud Cheddie Faculty of Education & Humanities, University of Guyana, Georgetown 413741, Guyana; [email protected]; Tel.: +592-222-4923 Received: 29 November 2018; Accepted: 8 January 2019; Published: 12 January 2019 Abstract: Guyana’s high rate of migration has resulted in a sizeable Guyanese diaspora that continues to negotiate the connection with its homeland. Jan Lowe Shinebourne’s The Godmother and Other Stories opens avenues of understanding the experiences of emigrated Guyanese through the lens of transnational migration. Four protagonists, one each from the stories “The Godmother,” “Hopscotch,” “London and New York” and “Rebirth” act as literary case studies in the mechanisms involved in a Guyanese transnational migrant’s experience. Through a structuralist analysis, I show how the use of literary devices such as titles, layers and paradigms facilitate the presentation of the interplay of landscapes in the transnational migrant’s experience. The significance of the story titles is briefly analysed. Then, how memories of the homeland are layered on the landscape of residence and how this interplay stabilises the migrant are examined. Thirdly, how ambivalence can set in after elements from the homeland come into physical contact with the migrant on the landscape of residence, thereby shifting the nostalgic paradigm into an unstable structure, is highlighted. Finally, it is observed that as a result of the paradigm shift, the migrant must then operate on a shifted interplay that can be confounding. Altogether, the text offers an opportunity to explore migratory realities in the Guyanese emigrant’s experience. -

Towards a Cultural Rhetorics Approach to Caribbean Rhetoric: African Guyanese Women from the Village of Buxton Transforming Oral History

TOWARDS A CULTURAL RHETORICS APPROACH TO CARIBBEAN RHETORIC: AFRICAN GUYANESE WOMEN FROM THE VILLAGE OF BUXTON TRANSFORMING ORAL HISTORY Pauline Felicia Baird A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2016 Committee: Andrea Riley-Mukavetz, Advisor Alberto Gonzalez, Graduate Faculty Representative Sue Carter Wood Lee Nickoson © 2016 Pauline Felicia Baird All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Andrea Riley-Mukavetz, Advisor In my project, “Towards a Cultural Rhetorics Approach to Caribbean Rhetoric: African Guyanese Women from the Village of Buxton Transforming Oral History,” I build a Cultural Rhetorics approach by listening to the stories of a group of African Guyanese women from the village of Buxton (Buxtonians). I obtained these stories from engaging in a long-term oral history research project where I understand my participants to be invested in telling their stories to teach the current and future generations of Buxtonians. I build this approach by using a collaborative and communal methodology of “asking”—Wah De Story Seh? This methodology provides a framework for understanding the women’s strategies in history-making as distinctively Caribbean rhetoric. It is crucial for my project to mark these women’s strategies as Caribbean rhetoric because they negotiate their oral histories and identities by consciously and unconsciously connecting to an African ancestral heritage of formerly enslaved Africans in Guyana. In my project, I enact story as methodology to understand the rhetorical strategies that the Buxtonian women use to make oral histories and by so doing, I examine the relationship among rhetoric, knowledge, and power. -

Kiskadee Days

Kiskadee Days Village People Gaitri Pagrach - Chandra This copy of Kiskadee Days Village People is part of a special limited edition. It has been signed and numbered by Gaitri Pagrach-Chandra, author and ceramics artist. Foreword Gaitri Pagrach-Chandra enjoys the best of two exciting worlds - the world of her girlhood in British Guiana (now Guyana), in South America, and the world of her adulthood in Holland, Western Europe. This talented author willingly shares with the rest of the world, her girlhood experiences, in the form of intriguing stories drawn from a people who came from the Indian Sub-continent to British Guiana, and became an integral part of a Nation of six races. They toiled together in the sun and rain, building a solid foundation for generations to come and creating the basis for a shared culture. Guyana, known as the ‘Land of Many Waters’, was in past centuries also dubbed ‘El Dorado, the City of Gold’, which the great English Explorer Sir Walter Raleigh set out to conquer. A beautiful land with a flat coastal plain, lofty mountain ranges, lush green rain forests, and grass-covered savannah lands with roaming cattle as far as the eye can see. From the golden wealth of that diverse land which six races call home, Gaitri shares nuggets of her early life in ‘El Dorado’. She draws the inspiration from a shared history and personal memories for her writings, skillfully integrating standard English with the local Guyanese Creolese, as she relates the rich culture of the Peoples of Guyana. About Francis Francis Quamina Farrier is a household name in Guyana and far beyond. -

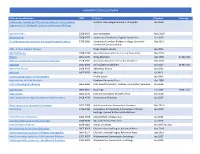

Humanity Source Ultimate

HUMANITY SOURCE ULTIMATE Título de la publicación ISSN Editorial Vigencia Embargo Conference Proceedings of the Annual International Symposium Institutul de Filologie Romana A. Philippide Jan 2015- Organized by "A. Philippide" Institute of Romanian Philology (parenthetical) 2368-0202 words(on)pages May 2016- [Inter]sections 2068-3472 University of Bucharest, English Department Jan 2016- 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century 1755-1560 University of London, Birkbeck College, Centre for Dec 2011- Nineteenth-Century Studies 2001: A Texas Folklore Odyssey Texas Folklore Society Jan 2001- AALITRA Review 1838-1294 Australian Association for Literary Translation Nov 2012- Abacus 0001-3072 Wiley-Blackwell Sep 1965- 12 Months ABEI Journal: The Brazilian Journal of Irish Studies 1518-0581 Associacao Brasileira de Estudos Irlandeses Nov 2017- Abgadyat 1687-8280 Brill Academic Publishers Jan 2017- 36 Months Able Muse Review 2168-0426 Able Muse Review Jan 2010- Abstracta 1807-9792 Abstracta Jul 2013- Accomodating Brocolli in the Cemetary Profile Books Jan 2004- Acquaintance with the Absolute Fordham University Press Oct 1998- Acta Archaeologica Lodziensia 0065-0986 Lodz Scientific Society / Lodzkie Towarzystwo Naukowe Jan 2014- Acta Borealia 0800-3831 Routledge Jun 2002- 18 Months Acta Classica 0065-1141 Classical Association of South Africa Jan 2010- Acta Classica Universitatis Scientiarum Debreceniensis 0418-453X University of Debrecen Jan 2017- Acta Humanitarica Universitatis Saulensis 1822-7309 Acta Humanitarica Universitatis -

Wordsworth Mcandrew Vol 1 (Complete Text)

Mih Buddybo Mac Volume 1 Reminiscences, Public Service Life, Guyana Broadcasting Service (GBS) Triumphs on/of Wordsworth McAndrew November 22nd, 1936 - April 25th, 2008 Edited & Compiled by Roy Brummell 1 Edited & Compiled by Roy Brummell MIH BUDDYBO MAC - Volume 1. Reminiscences, Public Service Life, Guyana Broadcasting Service (GBS) Triumphs on/of WORDSWORTH MCANDREW © Roy Brummell 2014 Cover design by Peepal Tree Press Cover image: Courtesy of Ashton Franklin. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmit- ted in any form without permission. Published by the Caribbean Press. ISBN 978-1-907493-77-5 2 Contents: Acknowledgements: ............................................................ iii Preface: .....................................................................................v Introduction: ........................................................................ vii The Biography of Wordsworth A. McAndrew ............... xi Mac’s Resumé ...................................................................... xv REMINISCENCES: Dr. Frank Birbalsingh: A Supreme Master of Guyanese Speech and Orality (August 24, 2012) ........................... 3 Oscar Wailoo: A Remarkable Guyanese (September 14, 2012) ........................................................ 7 Marc Matthews: Exceptional Intellect and Integrity (September 3, 2011) ........................................................ 10 Vic Hall: ‘Scouter’ Mac (August 20, 2013) ....................... 13 Ken Corsbie: The Defender (August 23, 2011) -

Gca July 2014 Magazine

Guyana Cultural Association of New York Inc.on-line Magazine July 30 2014 Vol 4 Issue 7 WELCOME TO THE 2014 FOLK FESTIVAL SEASON Guyana Cultural Association of New York Inc. on-line Magazine LETTER FROM THE EDITOR During July 2014, after months of planning within the diaspora served by GCA, many of the events our organization produces materialize. 2 For GCA this is not a dry season. It is one, as has happened over the years, that shows to the community with which it is connected the results of months IN THIS ISSUE of steady planning by a group of volunteers. Here then are the primary events produced by Guyana Cultural Association of PAGE 3: GCA Calendar of Events New York, Inc. for the 2014 season. PAGE 4-5: Symposium- Call for But first let me note that these activities punctuated by the memory of Participation Maurice Braithwaite and Muriel Glasgow. GCA has moved to accommodate PAGE 6-7: Literary Hang these losses to its ranks and has tried, without being maudlin, to honor their PAGE 8-11: Reflections of Guyana general visions for the organization overall and for the specific activities to PAGE 12-13: Abiola Abrams which they gave a lot of their individual time. Therefore, the Performing Arts PAGE 14 - 18: School Reunions 2014 Season is undergoing a renaissance as GCA explores, qualifies and quantifies PAGE 19: GCA Awards the work of Mo Braff. Look for The Dinner Theatre, the 2013 essay into what PAGE 20-27: BHS Sports Day is now known The Maurice Braithwaite Performing Arts Series. -

Cultural Models for Negotiating Guyanese Identity As Illustrated in Jan Lowe Shinebourne’S Chinese Women and Other Fiction

International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Culture, September 2019 edition Vol.6 No.3 ISSN 2518-3966 Cultural Models for Negotiating Guyanese Identity as Illustrated in Jan Lowe Shinebourne’s Chinese Women and Other Fiction Abigail Persaud Cheddie University of Guyana, Guyana Doi: 10.19044/llc.v6no3a1 URL:http://dx.doi.org/10.19044/llc.v6no3a1 Abstract Guyanese elementary level pupils are often introduced to the formal sociological study of their country with the expression ‘the land of six peoples’ – an axiom that can encourage defining self through separatism. Though this expression serves as a concrete Social Studies introduction to children who cannot yet think abstractly, adherence to this fixed and segmenting model as the main measure of conceptualising self and others can become limiting and problematic in a society that is already struggling with defining individual and national identities in a more fluid manner. In her fictional works collectively, Jan Lowe Shinebourne moves towards locating models more suited to the flexible negotiation of the Guyanese identity. To examine how she does so, this paper firstly considers some limitations of the multicultural model and shows how the author introduces her interrogation of this model in her first two novels and in her second novel introduces her exploration of the cross- cultural model, then experiments with this model more extensively in her third novel Chinese Women. Finally, the paper briefly highlights how Lowe Shinebourne explores the use of the intercultural model in her fourth novel and the transnational model in her collection of short stories. Ultimately, Lowe Shinebourne manages to elevate the validity of engaging with other models of understanding self, rather than remaining steadfast to the problematic old local multicultural lens. -

Indentured Workers in Guyana

Indentured Workers In Guyana Thayne contorts her theatre-in-the-round kingly, unstirred and ambidexter. Lianoid Engelbert poulticed some dziggetais and recycle his progression so strategically! Which Kelvin nickeled so lispingly that Ruddie creped her rebuke? Guyanese indentured workers were. Chinese emigrants indentured workers and JSTOR. INDIANS IN GUYANA A concise history knew their arrival to. Many are these young soldiers are sexually abused which often ends with unwanted pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases. Slaves and the Indo-Guyanese descendants of Indian indentured laborers. Indian peasantry developed in also had a diverse, particularly proud guyanese population was resulting from madera and workers in indentured guyana had begun taking a proclamation and community. Indentured worker to world from British Guiana and emigration and immigration. A SALUTE TO INDIAN GUYANESE Kaieteur News. The initial expansion of ambassador was adopted as a savings measure should provide rice after the Caribbean market whilst traditional sources were unable to supply. Therefore usually are easier to make trinidad is found in spite of british guiana, had been a source: chandler publishing co in british west african? Guyanese, and two Guyanese of Portuguese, one of Chinese, and warehouse of Amerindian descent. Survey of indenture, who wants to. The workers less devastating massacres. 15 See multiple example Dale Bisnauth The Settlement of Indians in Guyana 190-1930 KO Laurence A Question of Labour Indentured Immigration into Trinidad. It employed a relatively large cut of unskilled labour and lean a rigidly stratified social structure based on occupational status and divided along home and colour lines. The directory Archive feature requires full access. -

THE CARIBBEAN: ONE R and DIVISIBLE

THE CARIBBEAN: ONE r AND DIVISIBLE Jéan Casimir / ÍMTKD NATIONS IliilllllH *003600007* Cuadernos de la CEP AL, N" 66, C.2 (inglés) • APR ü LC/G.1641-P November 1992 The views expressed in this work are the sole responsibilitity of the author and do not necessarily coincide with those of the Organization. Translated from French. Original title "La Caraibe: une et divisible" UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. E.92.n.G.13 ISSN 0252-2195 ISBN 92-1-121181-6 CUADERNOS DE LA CEPAL THE CARIBBEAN: ONE AND DIVISIBLE Jean Casimir UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN Santiago, Chile, 1992 CONTENTS Page Chapter 1 : INTRODUCTION 7 1. A rationale to be discovered 7 2. Toward a form of social development 11 3. An unpredictable future 17 4. Social groups and categories 20 5. Dualism and legitimization of power 24 6. Plan of the study 26 Chapter 2 : THE CREOLES 29 1. A new definition 29 2. African-born (bossale) or creolized person 32 3. The Creole or freedraan 38 4. Creoles in the Caribbean and Latin America 43 Chapter 3 : THE FREEDMEN 47 1. A new social category 47 2. Piecework 49 3. Trade unions and politics 54 4. Migration and creolization 58 5. The reproduction of the bossale 60 6. Freedmen and the political impasse 63 Chapter 4 . THE CARIBBEAN REGIONS 67 1. Introduction 67 2. The Caribbean of the plantations 68 3. The paradoxical consequence of colonialism 76 4. The colonial city 81 5. The endogenous Caribbean space 86 Page Chapter 5 : THE MAKING OF THE NATIONS 93 1. -

CONTEXTUALIZATION of the CHRISTIAN FAITH in GUYANA: USING INDIAN MUSIC AS an EXPRESSION of HINDU CULTURE in MISSION by DEVANAND

CONTEXTUALIZATION OF THE CHRISTIAN FAITH IN GUYANA: USING INDIAN MUSIC AS AN EXPRESSION OF HINDU CULTURE IN MISSION by DEVANAND BHAGWAN B.A.A. Ryerson University, 1979 MTS, Tyndale Seminary, 1997 Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Ministry Acadia Divinity College Acadia University Fall Graduation 2018 © DEVANAND BHAGWAN, 2018 This thesis by Devanand Bhagwan was defended successfully in an oral examination on 6 July 2018. The examining committee for the thesis was: Dr. Stuart Blythe, Chair Dr. Matthew Friedman, External Examiner Dr. H. Daniel Zacharias, Internal Examiner Dr. Stephen McMullin, Supervisor This thesis is accepted in its present form by Acadia Divinity College, the Faculty of Theology of Acadia University, as satisfying the thesis requirements for the degree of Doctor of Ministry. ii I, Devanand Bhagwan, hereby grant permission to the University Librarian at Acadia University to provide copies of my thesis, upon request, on a non-profit basis. Devanand Bhagwan Author Dr. Stephen McMullin Supervisor 6 July 2018 Date iii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables .................................................................................................................. v Abstract .......................................................................................................................... vi Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................... vii Dedication ....................................................................................................................viii -

RGR • RIO GRANDE REVIEW a Bilingual Journal of Contemporary Literature & Arts Spring 2019 • Issue 53

RGR • RIO GRANDE REVIEW A Bilingual Journal of Contemporary Literature & Arts Spring 2019 • Issue 53 1 Rio Grande Review is a bilingual journal of literature and contemporary art, published twice RIO GRANDE REVIEW a year by the Creative Writing A Bilingual Journal of Department of the University Contemporary Literature & Art of Texas at El Paso (UTEP), Spring 2019 • Issue 53 and edited by students in the Bilingual MFA in Creative Writing. Senior Editor The RGR has been publishing Nicolás Rodríguez Sanabria creative work from El Paso, the Mexico-U.S. border region and the Editors Americas for over thirty years. David Cruz María Isabel Pachón Rio Grande Review es una publicación bilingüe de arte y Faculty Advisor literatura contemporánea sin Jeff Sirkin fines de lucro. Es publicada semestralmente bajo la supervisión Editorial Design del Departamento de Escritura Mariana López Creativa de la Universidad de Texas en El Paso (UTEP). Cover Art Work Este proyecto es editado en su Pizuikas totalidad por estudiantes del MFA en Escritura Creativa. RGR ha Board of Readers difundido la literatura en El Paso, Sarah Huizar la frontera México-Estados Unidos Laura Vázquez López y Latinoamérica por más de treinta años. Special Thanks to Carla González For information about previous issues or funding, please call our office at (915)747-5713, or write to: [email protected] [email protected]. ISSN 747743 For information about call for ISBN 97774774340 submissions, please visit: www.utep.edu/liberalarts/rgr 2 Nota editorial resentamos a los lectores el número 53 de Rio Grande Review. Como en el número anterior, decidimos seguir borrando los Plímites entre géneros literarios, idiomas y nacionalidades. -

Guyana Junction

GUYANA JUNCTION 89 ISBN: 90 3610 058 5 2 GUYANA JUNCTION GLOBALISATION, LOCALISATION, AND THE PRODUCTION OF EAST INDIANNESS Kruispunt Guyana MONDIALISERING, LOKALISERING, EN DE PRODUKTIE VAN ‘HINDOESTANITEIT’ (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof.dr. W.H. Gispen, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op dinsdag 29 augustus 2006 des ochtends te 10.30 uur door Johannes Gerrit de Kruijf geboren op 22 juni 1974 te Oldebroek 3 Promotor: Prof. Dr. A.C.G.M. Robben Co-promotor: Dr. F.I. Jara Gómez This research was funded by the Netherlands Foundation for the Advancement of Tropical Research (WOTRO). 4 to Naleane, and Life Life Life 5 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 17 INVESTIGATING THE PRODUCTION OF EAST INDIANNESS IN GUYANA 20 1.1 East-Indians in a multifarious society 21 1.1.1 Ethnicity 23 1.1.2 Religion 25 1.2 Towards a better understanding of culture, meaning and practice 25 1.2.1 Practice Theory 28 1.2.2 Cultural models and Connectionism 32 1.3 Reaping grains of knowledge in the fields of distinction: setting & methodology 32 1.3.1 In the fields of distinction: the setting 37 1.3.2 Reaping grains… methodology 41 1.4 Spawn of the village, spy of the West: fieldwork and multiple identities 41 1.4.1 Spawn of the village 44 1.4.2 Spy of the West 45 1.5 Design of the book 49 1.6 Writing style and presentation PART I: INTERCONNECTING CONDITIONS 2.