CONTEXTUALIZATION of the CHRISTIAN FAITH in GUYANA: USING INDIAN MUSIC AS an EXPRESSION of HINDU CULTURE in MISSION by DEVANAND

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume-13-Skipper-1568-Songs.Pdf

HINDI 1568 Song No. Song Name Singer Album Song In 14131 Aa Aa Bhi Ja Lata Mangeshkar Tesri Kasam Volume-6 14039 Aa Dance Karen Thora Romance AshaKare Bhonsle Mohammed Rafi Khandan Volume-5 14208 Aa Ha Haa Naino Ke Kishore Kumar Hamaare Tumhare Volume-3 14040 Aa Hosh Mein Sun Suresh Wadkar Vidhaata Volume-9 14041 Aa Ja Meri Jaan Kishore Kumar Asha Bhonsle Jawab Volume-3 14042 Aa Ja Re Aa Ja Kishore Kumar Asha Bhonsle Ankh Micholi Volume-3 13615 Aa Mere Humjoli Aa Lata Mangeshkar Mohammed RafJeene Ki Raah Volume-6 13616 Aa Meri Jaan Lata Mangeshkar Chandni Volume-6 12605 Aa Mohabbat Ki Basti BasayengeKishore Kumar Lata MangeshkarFareb Volume-3 13617 Aadmi Zindagi Mohd Aziz Vishwatma Volume-9 14209 Aage Se Dekho Peechhe Se Kishore Kumar Amit Kumar Ghazab Volume-3 14344 Aah Ko Chahiye Ghulam Ali Rooh E Ghazal Ghulam AliVolume-12 14132 Aah Ko Chajiye Jagjit Singh Mirza Ghalib Volume-9 13618 Aai Baharon Ki Sham Mohammed Rafi Wapas Volume-4 14133 Aai Karke Singaar Lata Mangeshkar Do Anjaane Volume-6 13619 Aaina Hai Mera Chehra Lata Mangeshkar Asha Bhonsle SuAaina Volume-6 13620 Aaina Mujhse Meri Talat Aziz Suraj Sanim Daddy Volume-9 14506 Aaiye Barishon Ka Mausam Pankaj Udhas Chandi Jaisa Rang Hai TeraVolume-12 14043 Aaiye Huzoor Aaiye Na Asha Bhonsle Karmayogi Volume-5 14345 Aaj Ek Ajnabi Se Ashok Khosla Mulaqat Ashok Khosla Volume-12 14346 Aaj Hum Bichade Hai Jagjit Singh Love Is Blind Volume-12 12404 Aaj Is Darja Pila Do Ki Mohammed Rafi Vaasana Volume-4 14436 Aaj Kal Shauqe Deedar Hai Asha Bhosle Mohammed Rafi Leader Volume-5 14044 Aaj -

That Continues with Swami Nalinanand Giri

THE HINDU TEMPLE OF METROPOLITAN WASHINGTON 10001 RIGGS ROAD, ADELPHI, MD 20783 PHONE #s 301-445-2165; http://www.hindutemplemd.org; E-mail: [email protected] December 2015 Scheduled Events - Everyone is invited - Please contact Hindu Temple Priests to sponsor Katha & Navratris Pooja / Priti Bhoj - Please visit our website www.hindutemplemd.org to view flyers for more details on special events Month Date Day Time Event Description Tuesday December 1 - Wednesday December 9 , 2015 - Amritwani Chaleese (40) Diwas MahaYagya that continues With Swami Nalinanand Giri with melodious bhajans, kirtan & Katha on Hanuman Chalisa Event Schedule: Weekdays: 7 pm to 9 pm & Weekends: 5 pm to 7 pm Sunday December 6: Hanumat Hawan - 12 Noon to 4pm & Paath 5pm to 7pm Monday December 7: Rudra Abhishek - 4pm to 7pm & Paath 5pm to 7pm Tuesday December 8: 108 Hanuman Chalisa - 1pm to 9pm Puran Ahuti - Wednesday, December 9, 2015: 6.30 pm to 9.30 pm We invite and welcome sponsors for these services Please contact: Preacher Swami Nalinanand Giri, Pandit Pitamber Dutt Sharma & Ram Kumar Shastri 301-445-2165; 301-434-1000. December 1 TUESDAY 7:00 PM to 9:00 PM Hanuman Chalisa Paath & AMRITWANIT By Swami Nalinanand Giri - Chaleese Diwas Yagya continues SATSANG & PAATH December 2 WEDNESDAY Laxmi Narayana Pooja Election Day December 2 WEDNESDAY 7:00 PM to 9:00 PM AMRITWANIT SATSANG & PAATH By Swami Nalinanand Giri - Chaleese Diwas Yagya continues December 3 THURSDAY 7:00 PM to 9:00 PM AMRITWANIT SATSANG & PAATH By Swami Nalinanand Giri - Chaleese Diwas Yagya -

Hindu Music from Various Authors, Pom.Pil.Ed and J^Ublished

' ' : '.."-","' i / i : .: \ CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY MUSIC e VerSl,y Ubrary ML 338.fl2 i882 3 1924 022 411 650 Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31 92402241 1 650 " HINDU MUSIC FROM VARIOUS AUTHORS, POM.PIL.ED AND J^UBLISHED RAJAH COMM. SOURINDRO MOHUN TAGORE, MUS. DOC.J F.R.S.L., M.U.A.S., Companion of the Order of the Indian Empire ; KNIGHT COMMANDER OF THE FIRST CLASS OF THE ORDER OF ALBERT, SAXONY ; OF THE ORDER OF LEOPOLD, BELGIUM ; FRANCIS OF THE MOST EXALTED ORDEE OF JOSEPH, AUSTRIA ; OF THE ROYAL ORDER OF THE CROWN OF ITALY ; OF THE MOST DISTINGUISHED ORDER OF DANNEBROG, DENMARK ; AND OF THE ROYAL ORDER OF MELTJSINE OF PRINCESS MARY OF LUSIGNAN ; FRANC CHEVALIER OF THE ORDER OF THE KNIGHTS OF THE MONT-REAL, JERUSALEM, RHODES HOLY SAVIOUR OF AND MALTA ; COMMANDEUR DE ORDRE RELIGIEOX ET MILITAIRE DE SAINT-SAUVEUR DE MONT-REAL, DE SAINT-JEAN DE JERUSALEM, TEMPLE, SAINT SEPULCRE, DE RHODES ET MALTE DU DU REFORME ; KNIGHT OF THE FIRST CLASS OF THE IMPERIAL ORDER OF THE " PAOU SING," OR PRECIOUS STAR, CHINA ; OF THE SECOND CLASS OF THE HIGH IMPERIAL ORDER OF THE LION AND SUN, PERSIA; OF THE SECOND CLASS OF THE IMPERIAL ORDER OF MEDJIDIE, TURKEY ; OF THE ROYAL MILITARY ORDER OF CHRIST, AND PORTUGAL ; KNIGHT THE OF BASABAMALA, OF ORDER SIAM ; AND OF THE GURKHA STAR, NEPAL ; " NAWAB SHAHZADA FROM THE SHAH OF PERSIA, &C, &C, &C. -

Hindu Music in Bangkok: the Om Uma Devi Shiva Band

Volume 22, 2021 – Journal of Urban Culture Research Hindu Music In Bangkok: The Om Uma Devi Shiva Band Kumkom Pornprasit+ (Thailand) Abstract This research focuses on the Om Uma Devi Shiva, a Hindu band in Bangkok, which was founded by a group of acquainted Hindu Indian musicians living in Thailand. The band of seven musicians earns a living by performing ritual music in Bangkok and other provinces. Ram Kumar acts as the band’s manager, instructor and song composer. The instruments utilized in the band are the dholak drum, tabla drum, harmonium and cymbals. The members of Om Uma Devi Shiva band learned their musical knowledge from their ancestors along with music gurus in India. In order to pass on this knowledge to future generations they have set up music courses for both Indian and Thai youths. The Om Uma Devi Shiva band is an example of how to maintain and present one’s original cultural identity in a new social context. Keywords: Hindu Music, Om Uma Devi Shiva Band, Hindu Indian, Bangkok Music + Kumkom Pornprasit, Professor, Faculty of Fine and Applied Arts, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand. email: [email protected]. Received 6/3/21 – Revised 6/5/21 – Accepted 6/6/21 Volume 22, 2021 – Journal of Urban Culture Research Hindu Music In Bangkok… | 218 Introduction Bangkok is a metropolitan area in which people of different ethnic groups live together, weaving together their diverse ways of life. Hindu Indians, considered an important ethnic minority in Bangkok, came to settle in Bangkok during the late 18 century A.D. to early 19 century A.D. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

An Introduction to The-History of Music Amongst

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE-HISTORY OF MUSIC AMONGST INDIAN SOUTH AFRICANS IN NATAL 1860-1948: 10WARDS MEL VEEN BETH J ACf::::'GN DURBAN JANUARY 1988 Of ~he hi stoczf ffiCISi C and mic and so; -political status Natal, 186<)- 1948. The study conce ns itself e:-:pr- essi on of musi c and the meanings associated with it. Music for-ms, music per-sonalities, and music functions ar-e tr-aced. Some expl anations of the rel a tionships between cl ass str-uctur-es, r- eligious expr-ession, political affiliation, and music ar-e suggested. The first chapter establishes the topic, par-ameters, motivation, pur-pose, theor-etical framewor-k, r esear-ch method and cons traints of the study. The main findings ar-e divided between two chronological sections, 1860-1920 and 1920-1948. The second chapter- describes early political and social structures, the South African phase of Gandhi's satyagraha, Muslim/Hindu festivals, early Christian activity, e arly organisation of a South Indian Hindu music group, the beginnings of the Lawrence family, and the sparking of interest in classical Indian music. The third chapter indicates the changing nature of occupation and life-style f rom a rural to an how music styles changed to suit t he new, Assimilation, assimilation music:: Ind :i. dn Ei s_ fo~ s.. Hindu an·I Muslim.. are identified. including both imported recorcl recor· / and the growth of the cl assi -al music movement ar-e traced, and the role of the "Indian II or-chestr·a is anal yst~d . Chapter· four presents the main conclusions, regarding the cultural, political, and social disposition of Indi a n South Africans, educational implications, and s ome areas requiring further research. -

The Sound of Belonging

The Sound of Belonging Music and Ethnic Identification among Marrons and Hindus in Paramaribo, Suriname Verena Brey Anne Goudzwaard Background picture: Hindu Dancer Small photograph: Marron Dance Group Both pictures were taken during a performance for festivities of the women's club “Soroptimist”, March 19th 2015. The Sound of Belonging Music and Ethnic Identification among Marrons and Hindus in Paramaribo, Suriname Verena Brey, 3920356 [email protected] Anne Goudzwaard 4028279 [email protected] Wordcount: 19192 Coordinator: Hans de Kruijf June 2015 Content 1.Introduction..............................................................................................................................9 2.Theoretical Frame..................................................................................................................13 2.1Ethnomusicology.............................................................................................................13 2.2The Role of Music in constructing Identity.....................................................................16 2.3Music and Ethnic Identity in the Context of Cultural Diversity and Creolization..........20 3.Introducing Suriname.............................................................................................................23 4.Marrons..................................................................................................................................24 4.1Introducing Marrons .......................................................................................................24 -

"Chant and Be Happy": Music, Beauty, and Celebration in a Utah Hare Krishna Community Sara Black

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 "Chant and Be Happy": Music, Beauty, and Celebration in a Utah Hare Krishna Community Sara Black Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC “CHANT AND BE HAPPY”: MUSIC, BEAUTY, AND CELEBRATION IN A UTAH HARE KRISHNA COMMUNITY By SARA BLACK A Thesis submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music The members of the Committee approve the Thesis of Sara Black defended on October 31, 2008. __________________________ Benjamin Koen Professor Directing Thesis __________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member __________________________ Michael Uzendoski Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________________________________ Douglass Seaton, Chair, Musicology ___________________________________________________________ Seth Beckman, Dean, College of Music The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures iv List of Photographs v Abstract vi INTRODUCTION: ENCOUNTERING KRISHNA 1 1. FAITH, AESTHETICS, AND CULTURE OF KRISHNA CONSCIOUSNESS 15 2. EXPERIENCE AND MEANING 33 3. OF KRISHNAS AND CHRISTIANS: SHARING CHANT 67 APPENDIX A: IRB APPROVAL 92 BIBLIOGRAPHY 93 BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH 99 iii LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1. Cymbal rhythm 41 Figure 2. “Mekala” beat and “Prabhupada” beat 42 Figure 3. Melodies for Maha Mantra 43-44 Figure 4. “Jaya Radha Madhava” 45 Figure 5. “Nama Om Vishnu Padaya” 47 Figure 6. “Jaya Radha Madhava” opening line 53 Figure 7. “Jaya Radha Madhava” with rhythmic pattern 53 Figure 8. “Jaya Radha Madhava” opening section 54 Figure 9. -

The Interplay of Landscapes in the Guyanese Emigrant's Reality in Jan Lowe Shinebourne's the Godmother

Article Migratory Realities: The Interplay of Landscapes in the Guyanese Emigrant’s Reality in Jan Lowe Shinebourne’s The Godmother and Other Stories Abigail Persaud Cheddie Faculty of Education & Humanities, University of Guyana, Georgetown 413741, Guyana; [email protected]; Tel.: +592-222-4923 Received: 29 November 2018; Accepted: 8 January 2019; Published: 12 January 2019 Abstract: Guyana’s high rate of migration has resulted in a sizeable Guyanese diaspora that continues to negotiate the connection with its homeland. Jan Lowe Shinebourne’s The Godmother and Other Stories opens avenues of understanding the experiences of emigrated Guyanese through the lens of transnational migration. Four protagonists, one each from the stories “The Godmother,” “Hopscotch,” “London and New York” and “Rebirth” act as literary case studies in the mechanisms involved in a Guyanese transnational migrant’s experience. Through a structuralist analysis, I show how the use of literary devices such as titles, layers and paradigms facilitate the presentation of the interplay of landscapes in the transnational migrant’s experience. The significance of the story titles is briefly analysed. Then, how memories of the homeland are layered on the landscape of residence and how this interplay stabilises the migrant are examined. Thirdly, how ambivalence can set in after elements from the homeland come into physical contact with the migrant on the landscape of residence, thereby shifting the nostalgic paradigm into an unstable structure, is highlighted. Finally, it is observed that as a result of the paradigm shift, the migrant must then operate on a shifted interplay that can be confounding. Altogether, the text offers an opportunity to explore migratory realities in the Guyanese emigrant’s experience. -

Towards a Cultural Rhetorics Approach to Caribbean Rhetoric: African Guyanese Women from the Village of Buxton Transforming Oral History

TOWARDS A CULTURAL RHETORICS APPROACH TO CARIBBEAN RHETORIC: AFRICAN GUYANESE WOMEN FROM THE VILLAGE OF BUXTON TRANSFORMING ORAL HISTORY Pauline Felicia Baird A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2016 Committee: Andrea Riley-Mukavetz, Advisor Alberto Gonzalez, Graduate Faculty Representative Sue Carter Wood Lee Nickoson © 2016 Pauline Felicia Baird All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Andrea Riley-Mukavetz, Advisor In my project, “Towards a Cultural Rhetorics Approach to Caribbean Rhetoric: African Guyanese Women from the Village of Buxton Transforming Oral History,” I build a Cultural Rhetorics approach by listening to the stories of a group of African Guyanese women from the village of Buxton (Buxtonians). I obtained these stories from engaging in a long-term oral history research project where I understand my participants to be invested in telling their stories to teach the current and future generations of Buxtonians. I build this approach by using a collaborative and communal methodology of “asking”—Wah De Story Seh? This methodology provides a framework for understanding the women’s strategies in history-making as distinctively Caribbean rhetoric. It is crucial for my project to mark these women’s strategies as Caribbean rhetoric because they negotiate their oral histories and identities by consciously and unconsciously connecting to an African ancestral heritage of formerly enslaved Africans in Guyana. In my project, I enact story as methodology to understand the rhetorical strategies that the Buxtonian women use to make oral histories and by so doing, I examine the relationship among rhetoric, knowledge, and power. -

Kiskadee Days

Kiskadee Days Village People Gaitri Pagrach - Chandra This copy of Kiskadee Days Village People is part of a special limited edition. It has been signed and numbered by Gaitri Pagrach-Chandra, author and ceramics artist. Foreword Gaitri Pagrach-Chandra enjoys the best of two exciting worlds - the world of her girlhood in British Guiana (now Guyana), in South America, and the world of her adulthood in Holland, Western Europe. This talented author willingly shares with the rest of the world, her girlhood experiences, in the form of intriguing stories drawn from a people who came from the Indian Sub-continent to British Guiana, and became an integral part of a Nation of six races. They toiled together in the sun and rain, building a solid foundation for generations to come and creating the basis for a shared culture. Guyana, known as the ‘Land of Many Waters’, was in past centuries also dubbed ‘El Dorado, the City of Gold’, which the great English Explorer Sir Walter Raleigh set out to conquer. A beautiful land with a flat coastal plain, lofty mountain ranges, lush green rain forests, and grass-covered savannah lands with roaming cattle as far as the eye can see. From the golden wealth of that diverse land which six races call home, Gaitri shares nuggets of her early life in ‘El Dorado’. She draws the inspiration from a shared history and personal memories for her writings, skillfully integrating standard English with the local Guyanese Creolese, as she relates the rich culture of the Peoples of Guyana. About Francis Francis Quamina Farrier is a household name in Guyana and far beyond. -

Humanity Source Ultimate

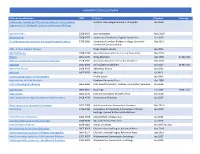

HUMANITY SOURCE ULTIMATE Título de la publicación ISSN Editorial Vigencia Embargo Conference Proceedings of the Annual International Symposium Institutul de Filologie Romana A. Philippide Jan 2015- Organized by "A. Philippide" Institute of Romanian Philology (parenthetical) 2368-0202 words(on)pages May 2016- [Inter]sections 2068-3472 University of Bucharest, English Department Jan 2016- 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century 1755-1560 University of London, Birkbeck College, Centre for Dec 2011- Nineteenth-Century Studies 2001: A Texas Folklore Odyssey Texas Folklore Society Jan 2001- AALITRA Review 1838-1294 Australian Association for Literary Translation Nov 2012- Abacus 0001-3072 Wiley-Blackwell Sep 1965- 12 Months ABEI Journal: The Brazilian Journal of Irish Studies 1518-0581 Associacao Brasileira de Estudos Irlandeses Nov 2017- Abgadyat 1687-8280 Brill Academic Publishers Jan 2017- 36 Months Able Muse Review 2168-0426 Able Muse Review Jan 2010- Abstracta 1807-9792 Abstracta Jul 2013- Accomodating Brocolli in the Cemetary Profile Books Jan 2004- Acquaintance with the Absolute Fordham University Press Oct 1998- Acta Archaeologica Lodziensia 0065-0986 Lodz Scientific Society / Lodzkie Towarzystwo Naukowe Jan 2014- Acta Borealia 0800-3831 Routledge Jun 2002- 18 Months Acta Classica 0065-1141 Classical Association of South Africa Jan 2010- Acta Classica Universitatis Scientiarum Debreceniensis 0418-453X University of Debrecen Jan 2017- Acta Humanitarica Universitatis Saulensis 1822-7309 Acta Humanitarica Universitatis