Delta Division Project History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

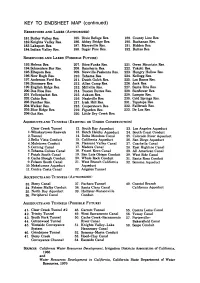

KEY to ENDSHEET MAP (Continued)

KEY TO ENDSHEET MAP (continued) RESERVOIRS AND LAKES (AUTHORIZED) 181.Butler Valley Res. 185. Dixie Refuge Res. 189. County Line Res. 182.Knights Valley Res. 186. Abbey Bridge Res. 190. Buchanan Res. 183.Lakeport Res. 187. Marysville Res. 191. Hidden Res. 184.Indian Valley Res. 188. Sugar Pine Res. 192. ButtesRes. RESERVOIRS AND LAKES 51BLE FUTURE) 193.Helena Res. 207. Sites-Funks Res. 221. Owen Mountain Res. 194.Schneiders Bar Res. 208. Ranchería Res. 222. Yokohl Res. 195.Eltapom Res. 209. Newville-Paskenta Res. 223. Hungry Hollow Res. 196. New Rugh Res. 210. Tehama Res. 224. Kellogg Res. 197.Anderson Ford Res. 211. Dutch Gulch Res. 225. Los Banos Res. 198.Dinsmore Res. 212. Allen Camp Res. 226. Jack Res. 199. English Ridge Res. 213. Millville Res. 227. Santa Rita Res. 200.Dos Rios Res. 214. Tuscan Buttes Res. 228. Sunflower Res. 201.Yellowjacket Res. 215. Aukum Res. 229. Lompoc Res. 202.Cahto Res. 216. Nashville Res. 230. Cold Springs Res. 203.Panther Res. 217. Irish Hill Res. 231. Topatopa Res. 204.Walker Res. 218. Cooperstown Res. 232. Fallbrook Res. 205.Blue Ridge Res. 219. Figarden Res. 233. De Luz Res. 206.Oat Res. 220. Little Dry Creek Res. AQUEDUCTS AND TUNNELS (EXISTING OR UNDER CONSTRUCTION) Clear Creek Tunnel 12. South Bay Aqueduct 23. Los Angeles Aqueduct 1. Whiskeytown-Keswick 13. Hetch Hetchy Aqueduct 24. South Coast Conduit 2.Tunnel 14. Delta Mendota Canal 25. Colorado River Aqueduct 3. Bella Vista Conduit 15. California Aqueduct 26. San Diego Aqueduct 4.Muletown Conduit 16. Pleasant Valley Canal 27. Coachella Canal 5. -

Westside-San Joaquin Integrated Regional Water Management Plan January 2019

San Luis & Delta-Mendota Water Authority 2019 Westside-San Joaquin Integrated Regional Water Management Plan January 2019 Prepared by: The 2019 Westside-San Joaquin Integrated Regional Water Management Plan was funded in part under the Water Quality, Supply, and Infrastructure Improvement Act of 2014 (Proposition 1), administered by the State of California, Department of Water Resources. 2019 Westside-San Joaquin Integrated Regional Water Management Plan Table of Contents Final Table of Contents Chapter 1 Governance ............................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1 Regional Water Management Group ............................................................................................ 1-1 1.2 History of IRWM Planning ............................................................................................................. 1-4 1.3 Governance ................................................................................................................................... 1-5 1.4 Coordination ................................................................................................................................. 1-8 1.5 WSJ IRWMP Adoption, Interim Changes, and Future Updates .................................................. 1-11 Chapter 2 Region Description ................................................................................................................. 2-1 2.1 IRWM Regional Boundary ............................................................................................................ -

RK Ranch 5732 +/- Acres Los Banos, CA Merced County

FARMS | RANCHES | RECREATIONAL PROPERTIES | LAND | LUXURY ESTATES RK Ranch 5732 +/- acres Los Banos, CA Merced County 707 Merchant Street | Suite 100 | Vacaville, CA 95688 707-455-4444 Office | 707-455-0455 Fax | californiaoutdoorproperties.com CalBRE# 01838294 FARMS | RANCHES | RECREATIONAL PROPERTIES | LAND | LUXURY ESTATES Introduction This expansive 5732 acre ranch is ideal for hunting, fishing, your favorite recreational activities, a family compound, agriculture, or cattle grazing. Located in Merced County, just an hour and a half from the San Francisco Bay Area, infinite recreational opportunities await with elk, trophy black tail deer, pigs, quail, and doves. The angler will be busy with catfish, bluegill, and outstanding bass fish- ing from the stock ponds. The South Fork of the Los Banos Creek flows through the property. This property is currently leased for cattle, but the recreational uses are only limited by your imagination. Location The property is located in Merced County, 17 miles from the town of Los Banos, 26 miles from Merced, and 8 miles from the San Luis Reservior. With all the benefits of seclusion, and the conveniences of major metropolitan areas close by, this property is just a 1.5 hour drive to Silicon Valley. Air service is provided by Fresno-Yosemite International Airport, 78 miles from the property, or Norman Y. Mi- neta San Jose International Airport, 83 miles from the property. Los Banos Municipal Airport is lo- cated 17 miles away. The closest schools would be 17 miles away in Los Banos. From the north, take Highway 101 South to CA-152 East, right onto Basalt Road, left onto Gonzaga Road. -

Bulletin 132-80 the California State Water Project—Current Activities

Department o Water Resource . Bulletin 132-8 The California State Water Project Current Activities ·and Future Management Plans .. October 1980 uey D. Johnson, Edmund G. Brown Jr. Ronald B. Robie ecretary for Resources Governor Director he Resources State of Department of . gency California Water Resources - ,~ -- performance levels corresponding to holder of the water rights. if the project capabilities as facilities are Contra Costa Canal should be relocated developed. Briefly, the levels of along a low-level alignment in the dt'velopmentcomprise: 1) prior to the future, the question of ECCID involve operation of New Melones, 2) after New ment will be considered at that time. Melones is operational but before operation of the Peripheral 'Canal, and SB 200, when implemented, will amend the 3) after the Peripheral Canal is oper California Water Code to include provi ational. sion that issues between the State and the delta water agencies concerning the The SDWA has indicated that the pro rights of users to make use of the posal is unacceptable. In March of waters of the Delta may be resolved by 1980, the Department proposed to reop .arbitration. en negotiation such that any differ- ·ences remaining between the Agency and WATER CONTRACTS MANAGEMENT the Department after September 30 be submitted to arbitration. The SDWA Thirty-one water agencies have entered also rejected that proposal. Before into long-term contracts with the State negotiations resume, SDWA wants to for annual water supplies from the State complete its joint study with WPRS. Water Project. A list of these agen The study concerns the CVP and SWP im cies, along with other information con pacts on south Delta water supplies. -

San Luis Transmission Project Final Environmental Impact

Appendix A Description of the Proposed Project and Alternatives San Luis Transmission Project 2. DESCRIPTION OF THE PROPOSED PROJECT AND ALTERNATIVES Chapter 2 Description of the Proposed Project and Alternatives This chapter describes the Proposed Project and alternatives; proposed construction, operation and maintenance, and decommissioning activities; and the Environmental Protection Measures (EPMs) and standard construction, operation, and maintenance practices that would be implemented as part of the Project. It also identifies the Environmentally Preferred Alternative. Pending completion of the EIS/EIR, the exact locations and quantities of project components (e.g., transmission line right-of-way, transmission line support structures, new substations or expanded substation areas, access roads, staging areas, pulling sites) are unknown and, in some cases, quantities of project components are estimated. This EIS/EIR uses the term Project area to collectively describe the area within which Project components could be located. A corridor is a linear area within which the easements (also known as rights-of-way) would be located; proposed corridors are part of the Project area. 2.1 Proposed Project Western proposes to construct, own, operate, and maintain about 95 miles of new transmission lines within easements ranging from 125 to 250 feet wide through Alameda, San Joaquin, Stanislaus, and Merced Counties along the foothills of the Diablo Range in the western San Joaquin Valley. Western also would upgrade or expand its existing substations, make the necessary arrangements to upgrade or expand existing PG&E substations, or construct new substations to accommodate the interconnections of these new transmission lines. An overview of the Proposed Project is illustrated in Figure 2-1. -

Nikola P. Prokopovich Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt4199s0f4 No online items Inventory of the Nikola P. Prokopovich Papers Finding aid created by Manuscript Archivist Elizabeth Phillips. Processing of this collection was funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and administered by the Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR), Cataloging Hidden Special Collections and Archives program. Department of Special Collections General Library University of California, Davis Davis, CA 95616-5292 Phone: (530) 752-1621 Fax: Fax: (530) 754-5758 Email: [email protected] © 2011 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Inventory of the Nikola P. D-229 1 Prokopovich Papers Creator: Prokopovich, Nikola P. Title: Nikola P. Prokopovich Papers Date: 1947-1994 Extent: 83 linear feet Abstract: The Nikola P. Prokopovich Papers document United States Bureau of Reclamation geologist Nikola Prokopovich's work on irrigation, land subsidence, and geochemistry in California. The collection includes draft reports and memoranda, published writings, slides, photographs, and two films related to several state-wide water projects. Prokopovich was particularly interested in the engineering geology of the Central Valley Project's canals and dam sites and in the effects of the state water projects on the surrounding landscape. Phyiscal location: Researchers should contact Special Collections to request collections, as many are stored offsite. Repository: University of California, Davis. General Library. Dept. of Special Collections. Davis, California 95616-5292 Collection number: D-229 Language of Material: Collection materials in English Biography Nikola P. Prokopovich (1918-1999) was a California-based geologist for the United States Bureau of Reclamation. He was born in Kiev, Ukraine and came to the United States in 1950. -

Water Quality Control Plan, Sacramento and San Joaquin River Basins

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Amendments to the 1994 Water Quality Control Plan for the Sacramento River and San Joaquin River Basins The Third Edition of the Basin Plan was adopted by the Central Valley Water Board on 9 December 1994, approved by the State Water Board on 16 February 1995 and approved by the Office of Administrative Law on 9 May 1995. The Fourth Edition of the Basin Plan was the 1998 reprint of the Third Edition incorporating amendments adopted and approved between 1994 and 1998. The Basin Plan is in a loose-leaf format to facilitate the addition of amendments. The Basin Plan can be kept up-to-date by inserting the pages that have been revised to include subsequent amendments. The date subsequent amendments are adopted by the Central Valley Water Board will appear at the bottom of the page. Otherwise, all pages will be dated 1 September 1998. Basin plan amendments adopted by the Regional Central Valley Water Board must be approved by the State Water Board and the Office of Administrative Law. If the amendment involves adopting or revising a standard which relates to surface waters it must also be approved by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) [40 CFR Section 131(c)]. -

Floods, Droughts, and Lawsuits: a Brief History of California Water Policy

1Floods, Droughts, and Lawsuits: A Brief History of California Water Policy MPI/GETTY IMAGES The history of California in the twentieth century is the story of a state inventing itself with water. William L. Kahrl, Water and Power, 1982 California’s water system might have been invented by a Soviet bureaucrat on an LSD trip. Peter Passell, “Economic Scene: Greening California,” New York Times, 1991 California has always faced water management challenges and always will. The state’s arid and semiarid climate, its ambitious and evolving economy, and its continually growing population have combined to make shortages and conflicting demands the norm. Over the past two centuries, California has tried to adapt to these challenges through major changes in water manage- ment. Institutions, laws, and technologies are now radically different from those brought by early settlers coming to California from more humid parts of the United States. These adaptations, and the political, economic, technologic, and social changes that spurred them on, have both alleviated and exacerbated the current conflicts in water management. This chapter summarizes the forces and events that shaped water man- agement in California, leading to today’s complex array of policies, laws, and infrastructure. These legacies form the foundation of California’s contemporary water system and will both guide and constrain the state’s future water choices.1 1. Much of the description in this chapter is derived from Norris Hundley Jr.’s outstanding book, The Great Thirst: Californians and Water: A History (Hundley 2001), Robert Kelley’s seminal history of floods in the Central Valley, Battling the Inland Sea (Kelley 1989), and Donald Pisani’s influential study of the rise of irrigated agriculture in California, From the Family Farm to Agribusiness: The Irrigation Crusade in California (Pisani 1984). -

CCID and Partners Pursue Los Banos Creek Detention Dam Project

News aNd INformatIoN from the CeNtral CalIfornia IrrIgatIoN dIstrict • www.ccidwater.org • Issue three • 2012 WATER RESOURCE PLAN CCID and Partners Pursue Los Banos Creek Detention Dam Project ■ STUDY SHOWS PROMISE FOR NEW SURFACE STORAGE AND GROUNDWATER RECHARGE BENEFITS FROM BUREAU-OWNED FACILITY. new feasibility study is showing in the facility for use promise for a partnership and release in the Abetween local interests, CCID summer during peak and other members of the Exchange irrigation,” White said. Contractors, the San Luis Water “This partnership would District, Grasslands Water District and produce mutual benefits the City of Los Banos to utilize the for all entities involved.” Los Banos Creek Detention Dam for additional water supply benefits. In addition to enhancing surface water storage, A proposed plan to re-operate the the new plan would existing Bureau of Reclamation facility enhance the availability for additional surface water and recharge of groundwater for benefits into Los Banos Creek is being municipal and farming examined this year as a first piece of the water supplies by Los Banos Creek Water Resource Plan. recharging area aquifers CCID General Manager Chris White through releases to said the feasibility study has revealed Los Banos Creek. a very promising project with multiple Historical groundwater benefits for the local partners. studies with the City of Los Banos show The Los Banos Creek Water Resource that Los Banos Creek Plan could provide significant benefits including, among other things, is a primary recharge improved water supply reliability, source for the aquifer recharge of local runoff, groundwater that feeds consumer and agricultural wells table stability, recreational and THIS AERIAL VIEW SHOWS THE PARAMETERS OF THE PROPOSED in the area. -

2. the Legacies of Delta History

2. TheLegaciesofDeltaHistory “You could not step twice into the same river; for other waters are ever flowing on to you.” Heraclitus (540 BC–480 BC) The modern history of the Delta reveals profound geologic and social changes that began with European settlement in the mid-19th century. After 1800, the Delta evolved from a fishing, hunting, and foraging site for Native Americans (primarily Miwok and Wintun tribes), to a transportation network for explorers and settlers, to a major agrarian resource for California, and finally to the hub of the water supply system for San Joaquin Valley agriculture and Southern California cities. Central to these transformations was the conversion of vast areas of tidal wetlands into islands of farmland surrounded by levees. Much like the history of the Florida Everglades (Grunwald, 2006), each transformation was made without the benefit of knowing future needs and uses; collectively these changes have brought the Delta to its current state. Pre-European Delta: Fluctuating Salinity and Lands As originally found by European explorers, nearly 60 percent of the Delta was submerged by daily tides, and spring tides could submerge it entirely.1 Large areas were also subject to seasonal river flooding. Although most of the Delta was a tidal wetland, the water within the interior remained primarily fresh. However, early explorers reported evidence of saltwater intrusion during the summer months in some years (Jackson and Paterson, 1977). Dominant vegetation included tules—marsh plants that live in fresh and brackish water. On higher ground, including the numerous natural levees formed by silt deposits, plant life consisted of coarse grasses; willows; blackberry and wild rose thickets; and galleries of oak, sycamore, alder, walnut, and cottonwood. -

Peripheral Canal

0 THE Volume 5, Number 4 RIPHERAL June 1981 CANAL ENVIRONS, a non-partisan environmental law natural resources newsletter published by King Hall School of Law, and edited by the Environmental Law Society, University of California, Davis. Designation of the employer or other affiliation of the author(s) of any article is given for purposes of identification of the author(s) only. The views expressed herein are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Uni- versity of California, School of Law, Envi- ronmental Law Society, or of any employer or organization with which an author is affiliated. Submission of Comments, Letters to the Editor, and Articles is encouraged. We reserve the right to edit and or print these materials. To the earliest Californians, conservation of water-the lifeblood Editorial Staff of all earth's children-was a sacred trust. Western water law, how- Editor-in-Chief ever, developed from the frontier ethic that whoever claimed some- Michael Endicott thing first owned it. Thus, in the California of 1981, water is treated Senior Editor and exploited as a commodity-a liquid gold. Woody Brooks Water is not scarce in California. Annual average run-off far Content Coordinator exceeds present and estimated future requirements. Unfortunately, George Wailes run-off occurs in winter and spring, when our needs are minimal. Editorial Coordinator Additionally, 70% of the total streamflow occurs north of Sacramento, Barb Malchick while 80% of the consumptive requirements lie farther to the south. California's extensive agricultural industry, which has rerouted large Manager Production amounts of surface water from marshlands to provide water for irriga- Anne Frassetto tion, is currently producing deserts. -

Report of the Task Force on California's Water Future Commission for Economic Development

Golden Gate University School of Law GGU Law Digital Commons California Agencies California Documents 4-1982 Report of the Task Force on California's Water Future Commission for Economic Development Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/caldocs_agencies Part of the Environmental Law Commons, Land Use Law Commons, and the Water Law Commons Recommended Citation Commission for Economic Development, "Report of the Task Force on California's Water Future" (1982). California Agencies. Paper 416. http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/caldocs_agencies/416 This Committee Report is brought to you for free and open access by the California Documents at GGU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in California Agencies by an authorized administrator of GGU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Report of the TASK FORCE ON CALIFORNIA'S WATER FUTURE STATE OF CALIFORNIA ~~.As C0MMISSION FOR ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT C33 Table of Contents I. Letter of Transmittal II. Executive Summary i III. Statement of Conclusions xi IV. Findings 1. The Task Force and the Issues 1 2. History of the Problem of Moving Water Through the Delta for Export 5 A. The Long tory of Alternative Delta Transfer Plans 5 B. Delta Water Quality Standards 11 3. DWR's Peripheral Canal 16 4. The Fisheries Questions 18 5. SB 200 23 A. Creation of the SB 200 Package - What It Includes 23 B. SB 200 - What It Will Cost 30 1. Cost Estimates 30 2. Assumptions Made Regarding Construction Scheduling, Costs, and Inflation Over the Construction Period 36 3.