Cvp Delta Division D3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Madera Subbasin

MADERA SUBBASIN Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) First Annual Report Prepared by Davids Engineering, Inc Luhdorff & Scalmanini ERA Economics April 2020 DRAFT Madera Subbasin Sustainable Groundwater Management Act First Annual Report April 2020 Prepared For Madera Subbasin Prepared By Davids Engineering, Inc Luhdorff & Scalmanini ERA Economics Table of Contents Table of Contents ......................................................................................................................... i List of Tables ............................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures ............................................................................................................................. ii List of Appendices ..................................................................................................................... iii List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................................. iv Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1 Executive Summary (§356.2.a) .................................................................................................. 2 Groundwater Elevations (§356.2.b.1) ........................................................................................ 6 Groundwater Level Monitoring ................................................................................................. -

Central Valley Project Integrated Resource Plan

Summary Report Central Valley Project Integrated Resource Plan U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Mid-Pacific Region TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND ..........................................................................................................................................................5 STUDY APPROACH ...................................................................................................................................................7 CLIMATE IMPACTS ON WATER SUPPLIES AND DEMANDS ...............................................................................11 COMPARISON OF PROJECTED WATER SUPPLIES AND DEMANDS .................................................................21 PERFORMANCE OF POTENTIAL FUTURE WATER MANAGEMENT ACTIONS .................................................27 PORTFOLIO TRADEOFFS .......................................................................................................................................37 CVP IRP STUDY LIMITATIONS ................................................................................................................................39 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS USED IN FIGURES ......................................................................................41 Tables Table 1. Simulation Suites and Assumptions Inlcuded in Each Portfolio .............................................................27 Figures Figure 1a. Projected changes in Temperature in Ensemble-Informed Transient Climate Scenarios between 2012 -

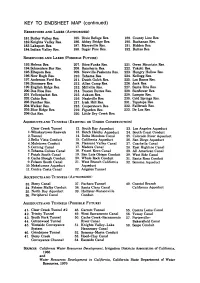

KEY to ENDSHEET MAP (Continued)

KEY TO ENDSHEET MAP (continued) RESERVOIRS AND LAKES (AUTHORIZED) 181.Butler Valley Res. 185. Dixie Refuge Res. 189. County Line Res. 182.Knights Valley Res. 186. Abbey Bridge Res. 190. Buchanan Res. 183.Lakeport Res. 187. Marysville Res. 191. Hidden Res. 184.Indian Valley Res. 188. Sugar Pine Res. 192. ButtesRes. RESERVOIRS AND LAKES 51BLE FUTURE) 193.Helena Res. 207. Sites-Funks Res. 221. Owen Mountain Res. 194.Schneiders Bar Res. 208. Ranchería Res. 222. Yokohl Res. 195.Eltapom Res. 209. Newville-Paskenta Res. 223. Hungry Hollow Res. 196. New Rugh Res. 210. Tehama Res. 224. Kellogg Res. 197.Anderson Ford Res. 211. Dutch Gulch Res. 225. Los Banos Res. 198.Dinsmore Res. 212. Allen Camp Res. 226. Jack Res. 199. English Ridge Res. 213. Millville Res. 227. Santa Rita Res. 200.Dos Rios Res. 214. Tuscan Buttes Res. 228. Sunflower Res. 201.Yellowjacket Res. 215. Aukum Res. 229. Lompoc Res. 202.Cahto Res. 216. Nashville Res. 230. Cold Springs Res. 203.Panther Res. 217. Irish Hill Res. 231. Topatopa Res. 204.Walker Res. 218. Cooperstown Res. 232. Fallbrook Res. 205.Blue Ridge Res. 219. Figarden Res. 233. De Luz Res. 206.Oat Res. 220. Little Dry Creek Res. AQUEDUCTS AND TUNNELS (EXISTING OR UNDER CONSTRUCTION) Clear Creek Tunnel 12. South Bay Aqueduct 23. Los Angeles Aqueduct 1. Whiskeytown-Keswick 13. Hetch Hetchy Aqueduct 24. South Coast Conduit 2.Tunnel 14. Delta Mendota Canal 25. Colorado River Aqueduct 3. Bella Vista Conduit 15. California Aqueduct 26. San Diego Aqueduct 4.Muletown Conduit 16. Pleasant Valley Canal 27. Coachella Canal 5. -

Transfer of the Central Valley Project

The Transfer of the Central Valley Project by Devin Odell In the spring of 1992, after six years of below-average rainfall, the perennial struggle over California's water reached a boiling point. Each of the three major groups of water interests in the state -- farmers, cities and environmentalists -- found themselves vying with the other two. At the center of this three-way tug of war was the biggest water hose in the state, the Central Valley Project (CVP), a massive set of dams, pumps, and canals built and run by the federal government. In February, CVP managers announced they could deliver less than 25 percent of the water normally used for agriculture. Farmers on about 1 million acres of land would get no water in 1992, and the rest were cut back to between 50 and 75 percent of their usual allocations. For the first time in 52 years, the CVP had completely failed some of its irrigators.' The period of low precipitation beginning in 1987 received most of the blame for this drastic step. But the Bureau of Reclamation, the federal agency in charge of the CVP, had also been forced to limit its agricultural deliveries in favor of other water users -- most notably, the Sacramento River's winter-run Chinook salmon.2 In 1981, 20,000 winter-run Chinook,listed as 'A state task force ... report stated] "threatened" under the federal Endangered that residential, business and Species Act and "endangered" under the state's municipal users might have only act, made the journey from the Pacific Ocean to half the water they would need by the spawning grounds upriver. -

Warren Act Contract for Kern- Tulare Water District and Lindsay- Strathmore Irrigation District

Environmental Assessment Warren Act Contract for Kern- Tulare Water District and Lindsay- Strathmore Irrigation District EA-12-069 U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Mid Pacific Region South-Central California Area Office Fresno, California January 2014 Mission Statements The mission of the Department of the Interior is to protect and provide access to our Nation’s natural and cultural heritage and honor our trust responsibilities to Indian Tribes and our commitments to island communities. The mission of the Bureau of Reclamation is to manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public. EA-12-069 Table of Contents Section 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Need for the Proposed Action............................................................................................. 1 1.3 Relevant Legal and Statutory Authorities........................................................................... 2 1.3.1 Warren Act .............................................................................................................. 2 1.3.2 Reclamation Project Act ......................................................................................... 2 1.3.3 Central Valley Project Improvement Act .............................................................. -

River West-Madera Master Plan

River West-Madera Master Plan APPENDICES Appendix A – River West-Madera Resource Assessment 39 | Page River West-Madera Master Plan River West- Madera Master Plan June 5, 2012 Resource Assessment The River West-Madera area consists of 795 acres of publicly owned land located in Madera County along the northern side of the San Joaquin River between Highway 41 and Scout Island. The Resource Assessment presents the area’s existing characteristics, as well as constraints and opportunities to future planning efforts. River West-Madera Master Plan River West-Madera Master Plan RESOURCE ASSESSMENT FIGURES ............................................................................................................................... 3 TABLES ................................................................................................................................. 4 EXISTING CHARACTERISITICS ............................................................................................. 5 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Land Use and History .............................................................................................................................. 7 Cultural History ...................................................................................................................................... 7 Sycamore Island ................................................................................................................................... -

Overview of The: Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Where Is the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta?

Overview of the: Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Where is the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta? To San Francisco Stockton Clifton Court Forebay / California Aqueduct The Delta Protecting California from a Catastrophic Loss of Water California depends on fresh water from the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta (Delta)to: Supply more than 25 million Californians, plus industry and agriculture Support $400 billion of the state’s economy A catastrophic loss of water from the Delta would impact the economy: Total costs to California’s economy could be $30-40 billion in the first five years Total job loss could exceed 30,000 Delta Inflow Sacramento River Delta Cross Channel San Joaquin River State Water Project Pumps Central Valley Project Pumps How Water Gets to the California Economy Land Subsidence Due to Farming and Peat Soil Oxidation - 30 ft. - 20 ft. - 5 ft. Subsidence ~ 1.5 ft. per decade Total of 30 ft. in some areas - 30 feet Sea Level 6.5 Earthquake—Resulting in 20 Islands Being Flooded Aerial view of the Delta while flying southwest over Sacramento 6.5 Earthquake—Resulting in 20 Islands Being Flooded Aerial view of the Delta while flying southwest over Sacramento 6.5 Earthquake—Resulting in 20 Islands Being Flooded Aerial view of the Delta while flying southwest over Sacramento 6.5 Earthquake—Resulting in 20 Islands Being Flooded Aerial view of the Delta while flying southwest over Sacramento 6.5 Earthquake—Resulting in 20 Islands Being Flooded Aerial view of the Delta while flying southwest over Sacramento 6.5 Earthquake—Resulting in 20 Islands Being Flooded Aerial view of the Delta while flying southwest over Sacramento 6.5 Earthquake—Resulting in 20 Islands Being Flooded Aerial view of the Delta while flying southwest over Sacramento The Importance of the Delta Water flowing through the Delta supplies water to the Bay Area, the Central Valley and Southern California. -

San Joaquin Exchange Contractors/Central California

San Joaquin River Exchange Contractors Water Authority Assembly Water Bond Hearing April 17, 2014 Mission Statement : To effectively protect the Exchange Contract and maximize local water supply, flexibility and redundancy in order to maintain local control over the members’ water supply, whatever circumstances occur.. 1 San Joaquin River Exchange Contractors Water Authority 2 The Exchange Contract - What is it Anyway? • The corner stone for the Development of the CVP ( Friant Dam, Shasta Dam, DMC) • Two documents were signed in 1939: 1. Exchange Contract • Monthly Delivery Limits, Flow Limits, Water Quality Criteria, Water Supply( Shasta) Criteria [ We operate under the 1967 Second Amended Contract] 2. Purchase Contract • Conveyed high flow rights, reserved low flow rights, We have our senior water rights on the San Joaquin River 3 Background of the Exchange Contractors . The SJRECWA is a Joint Powers Authority that was formed in 1992, its members include: • Central California Irrigation District (145,000 ac) • Columbia Canal Company (16,000 ac) • Firebaugh Canal Water District( 22,000 ac) • San Luis Canal Company (47,000 ac) . Main Duties: • Protect water rights • Administer AB 3030 Plans & Water Conservation Plans • Administer water transfers • Main point of contact for the administration of the Exchange Contract • Other duties as assigned 4 Background of the Exchange Contractors . Pre-1914 and Riparian Rights on the San Joaquin and Kings Rivers dating back to the 1870’s . Irrigate approximately 240,000 ac in Fresno, Madera Merced and Stanislaus Counties. Normal Year allocation 840,000 acre feet . Critical Year allocation 650,000 acre feet . Allocation is based on Forecasted inflow into Shasta Lake 5 Increased Regional Water Availability . -

Bulletin 132-80 the California State Water Project—Current Activities

Department o Water Resource . Bulletin 132-8 The California State Water Project Current Activities ·and Future Management Plans .. October 1980 uey D. Johnson, Edmund G. Brown Jr. Ronald B. Robie ecretary for Resources Governor Director he Resources State of Department of . gency California Water Resources - ,~ -- performance levels corresponding to holder of the water rights. if the project capabilities as facilities are Contra Costa Canal should be relocated developed. Briefly, the levels of along a low-level alignment in the dt'velopmentcomprise: 1) prior to the future, the question of ECCID involve operation of New Melones, 2) after New ment will be considered at that time. Melones is operational but before operation of the Peripheral 'Canal, and SB 200, when implemented, will amend the 3) after the Peripheral Canal is oper California Water Code to include provi ational. sion that issues between the State and the delta water agencies concerning the The SDWA has indicated that the pro rights of users to make use of the posal is unacceptable. In March of waters of the Delta may be resolved by 1980, the Department proposed to reop .arbitration. en negotiation such that any differ- ·ences remaining between the Agency and WATER CONTRACTS MANAGEMENT the Department after September 30 be submitted to arbitration. The SDWA Thirty-one water agencies have entered also rejected that proposal. Before into long-term contracts with the State negotiations resume, SDWA wants to for annual water supplies from the State complete its joint study with WPRS. Water Project. A list of these agen The study concerns the CVP and SWP im cies, along with other information con pacts on south Delta water supplies. -

American River Group Thursday, April 18Th, 2019 1:30 PM Central Valley Operation Office, Room 302 3310 El Camino Ave

American River Group Thursday, April 18th, 2019 1:30 PM Central Valley Operation Office, Room 302 3310 El Camino Ave. Sacramento, CA 95821 Conference Line: 1 (866) 718-0082; Passcode 2620147 JOIN WEBEX MEETING https://bor.webex.com/bor/j.php?MTID=m976285cf88d1078f4d1bdb60a280b92a Meeting number (access code): 907 429 279; Meeting password: CmfUCmGm 1. Participant Introductions (1:30-1:40) 2. Fisheries Updates (1:40-1:55) Cramer Fish Sciences Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission CDFW 3. Operations Forecast (1:55-2:10) SMUD PCWA Central Valley Operations 4. Temperature Management (2:10-2:25) Central Valley Operations 5. Discussion (2:25-2:55) Upcoming Presentations May - Climate Change, Dr. Swain 6. Schedule Next Meeting The next meeting is scheduled to take place on Thursday, May 16th, 2019 8. Adjourn American River Summary Conditions – March (On-going): • Snowpack is 165% of average for this date. • Flood control diagram now allowing filling of Folsom Reservoir. We are on our way up! Storage/Release Management Conditions • Releases to manage storage during fill and try to avoid excessive flow fluctuations. • Beginning water storage for next years operational needs. • Will be operating to new Army Corps flood control diagram on an interim basis until new Water Control Manual is signed, per letter from USACE. • MRR for April is 1,750 cfs. Temperature Management: • Upper Shutters in place on Units 2 and 3. Unit 1 is not in service. Upper shutters will be placed before it is returned to service. American River Operations Group (ARG) -

Northern Calfornia Water Districts & Water Supply Sources

WHERE DOES OUR WATER COME FROM? Quincy Corning k F k N F , M R , r R e er th th a a Magalia e Fe F FEATHER RIVER NORTH FORK Shasta Lake STATE WATER PROJECT Chico Orland Paradise k F S , FEATHER RIVER MIDDLE FORK R r STATE WATER PROJECT e Sacramento River th a e F Tehama-Colusa Canal Durham Folsom Lake LAKE OROVILLE American River N Yuba R STATE WATER PROJECT San Joaquin R. Contra Costa Canal JACKSON MEADOW RES. New Melones Lake LAKE PILLSBURY Yuba Co. W.A. Marin M.W.D. Willows Old River Stanislaus R North Marin W.D. Oroville Sonoma Co. W.A. NEW BULLARDS BAR RES. Ukiah P.U. Yuba Co. W.A. Madera Canal Delta-Mendota Canal Millerton Lake Fort Bragg Palermo YUBA CO. W.A Kern River Yuba River San Luis Reservoir Jackson Meadows and Willits New Bullards Bar Reservoirs LAKE SPAULDING k Placer Co. W.A. F MIDDLE FORK YUBA RIVER TRUCKEE-DONNER P.U.D E Gridley Nevada I.D. , Nevada I.D. Groundwater Friant-Kern Canal R n ia ss u R Central Valley R ba Project Yu Nevada City LAKE MENDOCINO FEATHER RIVER BEAR RIVER Marin M.W.D. TEHAMA-COLUSA CANAL STATE WATER PROJECT YUBA RIVER Nevada I.D. Fk The Central Valley Project has been founded by the U.S. Bureau of North Marin W.D. CENTRAL VALLEY PROJECT , N Yuba Co. W.A. Grass Valley n R Reclamation in 1935 to manage the water of the Sacramento and Sonoma Co. W.A. ica mer Ukiah P.U. -

Nikola P. Prokopovich Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt4199s0f4 No online items Inventory of the Nikola P. Prokopovich Papers Finding aid created by Manuscript Archivist Elizabeth Phillips. Processing of this collection was funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and administered by the Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR), Cataloging Hidden Special Collections and Archives program. Department of Special Collections General Library University of California, Davis Davis, CA 95616-5292 Phone: (530) 752-1621 Fax: Fax: (530) 754-5758 Email: [email protected] © 2011 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Inventory of the Nikola P. D-229 1 Prokopovich Papers Creator: Prokopovich, Nikola P. Title: Nikola P. Prokopovich Papers Date: 1947-1994 Extent: 83 linear feet Abstract: The Nikola P. Prokopovich Papers document United States Bureau of Reclamation geologist Nikola Prokopovich's work on irrigation, land subsidence, and geochemistry in California. The collection includes draft reports and memoranda, published writings, slides, photographs, and two films related to several state-wide water projects. Prokopovich was particularly interested in the engineering geology of the Central Valley Project's canals and dam sites and in the effects of the state water projects on the surrounding landscape. Phyiscal location: Researchers should contact Special Collections to request collections, as many are stored offsite. Repository: University of California, Davis. General Library. Dept. of Special Collections. Davis, California 95616-5292 Collection number: D-229 Language of Material: Collection materials in English Biography Nikola P. Prokopovich (1918-1999) was a California-based geologist for the United States Bureau of Reclamation. He was born in Kiev, Ukraine and came to the United States in 1950.