Cvp Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Madera Subbasin

MADERA SUBBASIN Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) First Annual Report Prepared by Davids Engineering, Inc Luhdorff & Scalmanini ERA Economics April 2020 DRAFT Madera Subbasin Sustainable Groundwater Management Act First Annual Report April 2020 Prepared For Madera Subbasin Prepared By Davids Engineering, Inc Luhdorff & Scalmanini ERA Economics Table of Contents Table of Contents ......................................................................................................................... i List of Tables ............................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures ............................................................................................................................. ii List of Appendices ..................................................................................................................... iii List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................................. iv Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1 Executive Summary (§356.2.a) .................................................................................................. 2 Groundwater Elevations (§356.2.b.1) ........................................................................................ 6 Groundwater Level Monitoring ................................................................................................. -

Central Valley Project Overview July 2013 Central Valley of California

Central Valley Project Overview July 2013 Central Valley of California TRINITY DAM FOLSOM DAM LV SL Hydrologic Constraints • Majority of water supply in the north • Most of the precipitation is in the winter/spring • Majority of demand in the south • Most of that demand is in the summer Geographic Constraints Sacramento/San Joaquin Delta Avg Annual Inflow in MAF (Billion Cu Meters) (5.3) 4.3 (1.7) 1.4 (1.1) 0.9 21.2 (26.2) Sacramento Delta Precip Eastside Streams San Joaquin California Water Projects • State Water Project • Central Valley Project • Local Water Projects Trinity CVP Shasta Major Storage Folsom Facilities New Melones Friant San Luis Trinity CVP Shasta Conveyance Folsom Facilities New Melones Friant San Luis CVP Features Summary • 18 Dams and Reservoirs • 500 Miles (800 Kilometers) of Canals • 11 Powerplants • 10 Pumping Plants • 20 Percent of State’s Developed Water Supply (about 7 million acre-feet, 8.6 billion cu meters) • 30 Percent of the State’s Agricultural Supply (about 3 mil acres of farm land, 1.2 mil hectares) • 13 Percent of State’s M&I Supply (about 2 million people served) CVP Authorized Purposes • Flood Control • River Regulation (Navigation) • Fish and Wildlife Needs • Municipal & Agricultural Water Supplies • Power Generation • Recreation TRINITY CVP - SWP FEATURES LEWISTON SHASTA SPRING CREEK POWERPLANT CARR POWERPLANT TINITY RIVER WHISKEYTOWN OROVILLE (SWP) TO SAN FRANCISCO BAY DELTA FOLSOM BANKS PP (SWP) JONES PP NEW MELONES O’NEILL TO SAN FELIPE SAN LUIS FRIANT TRINITY CVP - SWP FEATURES LEWISTON SHASTA -

Two-Dimensional Hydraulic Model of Folsom Dam

Michael Pantell, E.I.T. Peterson Brustad Inc. • Model Folsom Dam Flood Scenarios • During Probable Maximum Flood (PMF) • Varying Folsom Dam Outflows • Multiple Breach Locations and Methods • Results • Floodplain Depths • Mortality • Property Damage • Why? • Information not Available to public • To Obtain Masters Degree Built in 1956 Owned by USBR Storage Approx. 1 Mil Ac-ft 12 structures Concrete Main dam Earthen 2 Wing Dams 1 Auxiliary Dam Reference: USBR “Folsom Dam Facility Map” 8 Dikes Sacramento Folsom River Reservoir Sacramento American River Probable Maximum Flood American River 1000000 900000 Peak ≈ 900,000 cfs Basin 800000 700000 PMF 600000 ) cfs Developed by 500000 Flow ( USACE 400000 300000 Project Design 200000 Flood 100000 0 0 12 24 36 48 60 72 84 96 108 120 132 144 156 168 180 192 Approx. 25,000 Time (hours) year event Auxiliary Spillway Powerhouse Folsom Dam Flow = 6900 cfs 8 Tainter Gates 5- Main 3- Emergency Auxiliary Spillway Designed to PMF event Dam Outflow 500 PMF Event 490 Overtopping 480 Elevation 470 460 450 440 430 420 410 400 Elevation (NAVD88 feet) Elevation 390 380 370 360 350 50000 100000 150000 200000 250000 300000 350000 400000 450000 500000 550000 600000 650000 700000 750000 800000 850000 900000 950000 1000000 Outflow (CFS) Without Spillway With Spillway Mechanisms Overtopping Piping Earthquake Etc Right Wing Dam Northern Breach Mormon Auxiliary Dam Southern Breach Tallest and longest earthen structures North Earthen structure South Earthen structure LargerMacDonald Breach Von Thun = Longer & MacDonald Formation Von TimeThun & ∝ MacDonald, et. al.et. al. Gillette et. al. Gillette Large Breach Width Long- ft Formation3047 Time 374 3916 331 Von Thun & Gillete Height Small- ft Breach 47 47 76 76 Short Formation Time Formation 4.4 0.8 4.1 0.7 Time (hrs) HEC RAS 5.0 2D Mesh 150 m x 150 m Terrain CVFED 1 m resolution Manning’s n Based on CVFED Land Use Jonkman et. -

Central Valley Project Integrated Resource Plan

Summary Report Central Valley Project Integrated Resource Plan U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Mid-Pacific Region TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND ..........................................................................................................................................................5 STUDY APPROACH ...................................................................................................................................................7 CLIMATE IMPACTS ON WATER SUPPLIES AND DEMANDS ...............................................................................11 COMPARISON OF PROJECTED WATER SUPPLIES AND DEMANDS .................................................................21 PERFORMANCE OF POTENTIAL FUTURE WATER MANAGEMENT ACTIONS .................................................27 PORTFOLIO TRADEOFFS .......................................................................................................................................37 CVP IRP STUDY LIMITATIONS ................................................................................................................................39 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS USED IN FIGURES ......................................................................................41 Tables Table 1. Simulation Suites and Assumptions Inlcuded in Each Portfolio .............................................................27 Figures Figure 1a. Projected changes in Temperature in Ensemble-Informed Transient Climate Scenarios between 2012 -

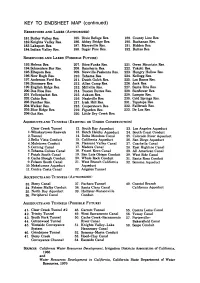

KEY to ENDSHEET MAP (Continued)

KEY TO ENDSHEET MAP (continued) RESERVOIRS AND LAKES (AUTHORIZED) 181.Butler Valley Res. 185. Dixie Refuge Res. 189. County Line Res. 182.Knights Valley Res. 186. Abbey Bridge Res. 190. Buchanan Res. 183.Lakeport Res. 187. Marysville Res. 191. Hidden Res. 184.Indian Valley Res. 188. Sugar Pine Res. 192. ButtesRes. RESERVOIRS AND LAKES 51BLE FUTURE) 193.Helena Res. 207. Sites-Funks Res. 221. Owen Mountain Res. 194.Schneiders Bar Res. 208. Ranchería Res. 222. Yokohl Res. 195.Eltapom Res. 209. Newville-Paskenta Res. 223. Hungry Hollow Res. 196. New Rugh Res. 210. Tehama Res. 224. Kellogg Res. 197.Anderson Ford Res. 211. Dutch Gulch Res. 225. Los Banos Res. 198.Dinsmore Res. 212. Allen Camp Res. 226. Jack Res. 199. English Ridge Res. 213. Millville Res. 227. Santa Rita Res. 200.Dos Rios Res. 214. Tuscan Buttes Res. 228. Sunflower Res. 201.Yellowjacket Res. 215. Aukum Res. 229. Lompoc Res. 202.Cahto Res. 216. Nashville Res. 230. Cold Springs Res. 203.Panther Res. 217. Irish Hill Res. 231. Topatopa Res. 204.Walker Res. 218. Cooperstown Res. 232. Fallbrook Res. 205.Blue Ridge Res. 219. Figarden Res. 233. De Luz Res. 206.Oat Res. 220. Little Dry Creek Res. AQUEDUCTS AND TUNNELS (EXISTING OR UNDER CONSTRUCTION) Clear Creek Tunnel 12. South Bay Aqueduct 23. Los Angeles Aqueduct 1. Whiskeytown-Keswick 13. Hetch Hetchy Aqueduct 24. South Coast Conduit 2.Tunnel 14. Delta Mendota Canal 25. Colorado River Aqueduct 3. Bella Vista Conduit 15. California Aqueduct 26. San Diego Aqueduct 4.Muletown Conduit 16. Pleasant Valley Canal 27. Coachella Canal 5. -

Newlands Project

MP Region Public Affairs, 916-978-5100, http://www.usbr.gov/mp, February 2016 Mid-Pacific Region, Newlands Project History The Newlands Project was one of the first Reclamation projects. It provides irrigation water from the Truckee and Carson Rivers for about 57,000 acres of cropland in the Lahontan Valley near Fallon and bench lands near Fernley in western Nevada. In addition, water from about 6,000 acres of project land has been transferred to the Lahontan Valley Wetlands near Fallon. Lake Tahoe Dam, a small dam at the outlet of Lake Tahoe, the source of the Truckee Lake Tahoe Dam and Reservoir River, controls releases into the river. Downstream, the Derby Diversion Dam diverts the water into the Truckee Canal and Lahontan Dam, Reservoir, carries it to the Carson River. Other features and Power Plant include Lahontan Dam and Reservoir, Carson River Diversion Dam, and Old Lahontan Dam and Reservoir on the Carson Lahontan Power Plant. The Truckee-Carson River store the natural flow of the Carson project (renamed the Newlands Project) was River along with water diverted from the authorized by the Secretary of the Interior Truckee River. The dam, completed in 1915, on March 14, 1903. Principal features is a zoned earthfill structure. The reservoir include: has a storage capacity of 289,700 acre-feet. Old Lahontan Power Plant, immediately below Lahontan Dam, has a capacity of Lake Tahoe Dam 42,000 kilowatts. The plant was completed in 1911. Lake Tahoe Dam controls the top six feet of Lake Tahoe. With the surface area of the lake, this creates a reservoir of 744,600 acre- Truckee Canal feet capacity and regulates the lake outflow into the Truckee River. -

Riverine Nutrient Trends in the Sacramento and San Joaquin Basins, California

Peer Reviewed Title: Riverine Nutrient Trends in the Sacramento and San Joaquin Basins, California: A Comparison to State and Regional Water Quality Policies Journal Issue: San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science, 13(4) Author: Schlegel, Brandon, California State University, Sacramento Domagalski, Joseph L., U.S Geological Survey, California Water Science Center Publication Date: 2015 Permalink: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/4c37m6vz Keywords: Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta, nutrients, nitrogen, phosphorus, nutrient transport, nutrient loads, agricultural drainage Local Identifier: jmie_sfews_29499 Abstract: doi: http://dx.doi.org/1015447/sfews.2015v13iss4art2 Non-point source (NPS) contaminant control strategies were initiated in California in the late 1980s under the authority of the State Porter–Cologne Act and eventually for the development of total maximum daily load (TMDL) plans, under the federal Clean Water Act. Most of the NPS TMDLs developed for California’s Central Valley (CV) region were related to pesticides, but not nutrients. Efforts to reduce pesticide loads and concentrations began in earnest around 1990. The NPS control strategies either encouraged or mandated the use of management practices (MPs). Although TMDLs were largely developed for pesticides, the resultant MPs might have affected the runoff of other potential contaminants (such as nutrients). This study evaluates the effect of agricultural NPS control strategies implemented in California’s CV before and between 1990 and 2013, on nutrients, by comparing trends in surface-water concentrations and loads. In general, use of MPs was encouraged during a “voluntary” period (1990 to 2004) and mandated during an “enforcement” period (2004 to 2013). Nutrient concentrations, loads, and trends were estimated by using a recently developed Weighted Regressions on Time, Discharge, and Season (WRTDS) model. -

Tri-Dam Project

AGENDA MATERIALS TRI-DAM PROJECT TRI-DAM POWER AUTHORITY \\IJ IJ\\ BOARD MEETING March 19, 2020 REGULAR BOARD MEETING AGENDA TRI-DAM PROJECT of THE OAKDALE IRRIGATION DISTRICT and THE SOUTH SAN JOAQUIN IRRIGATION DISTRICT MARCH 19, 2020 8:00A.M. CALL TO ORDER: Oakdale Irrigation District 1205 East F Street Oakdale, CA 95361 PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE ROLL CALL: John Holbrook, Bob Holmes, Dave Kamper, Ralph Roos, Mike Weststeyn Gail Altieri, Brad DeBoer, Herman Doornenbal, Tom Orvis, Linda Santos PUBLIC COMMENT: The Joint Board of Directors encourages publi c participation at Board meetings. Matters affecting the operation of the Tri-Dam Project and under the jurisdiction of the Joint Districts and not posted on the Agenda may be addressed by the publi c, and limited to 5 minutes per person. California law prohibits the Board from taking action on any matter that is not on the posted Agenda unless the Board determines that it is a situation specified in Government Code Subsection 54954.2. CONSENT CALENDAR ITEMS 1-2 l. Approve the regular board meeting minutes of February 20, 2020. 2. Approve February 2020 financial statements and statement of obligations. a. Investment p01tfolio and reserve fund status. ACTION CALENDAR ITEMS 3- 11 3. Discussion and possible action to approve annual fee for use of Federal Lands for operations of the Tri-Dam Project 4. Discussion and possible action to authorize the General Manager to sign the Professional Services Agreement with Gannett Fleming, Inc. for the preparation of the dam breach analysis and updated inundation mapping for Beardsley, Donnells, Tulloch and Goodwin Projects, including a budget adjustment for Account #59690. -

Executive Summary

Preliminary Mitigated Negative Declaration Date: January 9, 2019 Case No.: 2016-006868ENV Project Title: SFPUC Reliable Power Project Project Location: Portions of the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission Rights of Way in Stanislaus, Mariposa, and Tuolumne Counties Zoning: Various Project Sponsor San Francisco Public Utilities Commission Antonia Sivyer (415) 554-2474 Lead Agency: San Francisco Planning Department Staff Contact: Timothy Johnston – (415) 575-9035 [email protected] PROJECT DESCRIPTION: The San Francisco Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC) proposes to implement the Reliable Power Project (proposed project) for maintaining the reliability of the SFPUC’s electrical transmission system between the Holm and Kirkwood Powerhouses and the Warnerville Substation. The project includes implementation of a long-term vegetation management program that would address the North American Electric Reliability Corporation’s reliability standard (FAC-003) and other regulatory requirements that seek to minimize the risk of power outages and fires from vegetation contact with transmission lines on or near the right of way for electrical transmission lines1. In addition to implementation of the vegetation management program, the proposed project would include repairs and replacements for culverts associated with transmission line access roads and construction of a sand storage shed to stockpile sand for winter road treatments needed for access during winter months. Construction activities associated with the proposed project would occur within existing SFPUC facility and right of way boundaries in Stanislaus County, Mariposa County, and Tuolumne County, and would not require the acquisition of new property. Project implementation involving vegetation management would be ongoing. Construction activities and duration for culvert repair and/or replacement would vary along the transmission corridor, but would be short-term in nature, generally requiring a few of days to a couple of weeks to complete. -

Transfer of the Central Valley Project

The Transfer of the Central Valley Project by Devin Odell In the spring of 1992, after six years of below-average rainfall, the perennial struggle over California's water reached a boiling point. Each of the three major groups of water interests in the state -- farmers, cities and environmentalists -- found themselves vying with the other two. At the center of this three-way tug of war was the biggest water hose in the state, the Central Valley Project (CVP), a massive set of dams, pumps, and canals built and run by the federal government. In February, CVP managers announced they could deliver less than 25 percent of the water normally used for agriculture. Farmers on about 1 million acres of land would get no water in 1992, and the rest were cut back to between 50 and 75 percent of their usual allocations. For the first time in 52 years, the CVP had completely failed some of its irrigators.' The period of low precipitation beginning in 1987 received most of the blame for this drastic step. But the Bureau of Reclamation, the federal agency in charge of the CVP, had also been forced to limit its agricultural deliveries in favor of other water users -- most notably, the Sacramento River's winter-run Chinook salmon.2 In 1981, 20,000 winter-run Chinook,listed as 'A state task force ... report stated] "threatened" under the federal Endangered that residential, business and Species Act and "endangered" under the state's municipal users might have only act, made the journey from the Pacific Ocean to half the water they would need by the spawning grounds upriver. -

Figure 6-3. California's Water Infrastructure Network

DA 17 DA 67 DA 68 DA 22 DA 29 DA 39 DA 40 DA 41 DA 46 N. FORK N. & M. TUOLOMNE YUBA RIVER FORKS CHERRY CREEK, RIVER Figure 6-3. California's Water Infrastructure ELEANOR CREEK AMERICAN M & S FORK RIVER YUBA RIVER New Bullards Hetch Hetchy Res Bar Reservoir GREENHORN O'Shaughnessy Dam Network Configuration for CALVIN (1 of 2) SR- S. FORK NBB CREEK & BEAR DA 32 SR- D17 AMERICAN RIVER HHR DA 42 DA 43 DA 44 RIVER STANISLAUS SR- LL- C27 RIVER & 45 Camp Far West Reservoir DRAFT Folsom Englebright C31 Lake DA 25 DA 27 Canyon Tunnel FEATHER Lake 7 SR- CALAVERAS New RIVER SR-EL CFW SR-8 RIVER Melones Lower Cherry Creek MERCED MOKELUMNE Reservoir SR-10 Aqueduct ACCRETION CAMP C44 RIVER FAR WEST TO DEER CREEK C28 FRENCH DRY RIVER CREEK WHEATLAND GAGE FRESNO New Hogan Lake Oroville DA 70 D67 SAN COSUMNES Lake RIVER SR- 0 SR-6 C308 SR- JOAQUIN Accretion: NHL C29 RIVER 81 CHOWCHILLA American River RIVER New Don Lake McClure Folsom to Fair D9 DRY Pardee Pedro SR- New Exchequer RIVER Oaks Reservoir 20 CREEK Reservoir Dam SR- Hensley Lake DA 14 Tulloch Reservoir SR- C33 Lake Natoma PR Hidden Dam Nimbus Dam TR Millerton Lake SR-52 Friant Dam C23 KELLY RIDGE Accretion: Eastside Eastman Lake Bypass Accretion: Accretion: Buchanan Dam C24 Yuba Urban DA 59 Camanche Melones to D16 Upper Merced D64 SR- C37 Reservoir C40 2 SR-18 Goodwin River 53 D62 SR- La Grange Dam 2 CR Goodwin Reservoir D66 Folsom South Canal Mokelumne River Aqueduct Accretion: 2 D64 depletion: Upper C17 D65 Losses D85 C39 Goodwin to 3 Merced River 3 3a D63 DEPLETION mouth C31 2 C25 C31 D37 -

Warren Act Contract for Kern- Tulare Water District and Lindsay- Strathmore Irrigation District

Environmental Assessment Warren Act Contract for Kern- Tulare Water District and Lindsay- Strathmore Irrigation District EA-12-069 U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Mid Pacific Region South-Central California Area Office Fresno, California January 2014 Mission Statements The mission of the Department of the Interior is to protect and provide access to our Nation’s natural and cultural heritage and honor our trust responsibilities to Indian Tribes and our commitments to island communities. The mission of the Bureau of Reclamation is to manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public. EA-12-069 Table of Contents Section 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Need for the Proposed Action............................................................................................. 1 1.3 Relevant Legal and Statutory Authorities........................................................................... 2 1.3.1 Warren Act .............................................................................................................. 2 1.3.2 Reclamation Project Act ......................................................................................... 2 1.3.3 Central Valley Project Improvement Act ..............................................................