Report of the Task Force on California's Water Future Commission for Economic Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

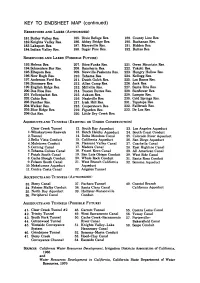

KEY to ENDSHEET MAP (Continued)

KEY TO ENDSHEET MAP (continued) RESERVOIRS AND LAKES (AUTHORIZED) 181.Butler Valley Res. 185. Dixie Refuge Res. 189. County Line Res. 182.Knights Valley Res. 186. Abbey Bridge Res. 190. Buchanan Res. 183.Lakeport Res. 187. Marysville Res. 191. Hidden Res. 184.Indian Valley Res. 188. Sugar Pine Res. 192. ButtesRes. RESERVOIRS AND LAKES 51BLE FUTURE) 193.Helena Res. 207. Sites-Funks Res. 221. Owen Mountain Res. 194.Schneiders Bar Res. 208. Ranchería Res. 222. Yokohl Res. 195.Eltapom Res. 209. Newville-Paskenta Res. 223. Hungry Hollow Res. 196. New Rugh Res. 210. Tehama Res. 224. Kellogg Res. 197.Anderson Ford Res. 211. Dutch Gulch Res. 225. Los Banos Res. 198.Dinsmore Res. 212. Allen Camp Res. 226. Jack Res. 199. English Ridge Res. 213. Millville Res. 227. Santa Rita Res. 200.Dos Rios Res. 214. Tuscan Buttes Res. 228. Sunflower Res. 201.Yellowjacket Res. 215. Aukum Res. 229. Lompoc Res. 202.Cahto Res. 216. Nashville Res. 230. Cold Springs Res. 203.Panther Res. 217. Irish Hill Res. 231. Topatopa Res. 204.Walker Res. 218. Cooperstown Res. 232. Fallbrook Res. 205.Blue Ridge Res. 219. Figarden Res. 233. De Luz Res. 206.Oat Res. 220. Little Dry Creek Res. AQUEDUCTS AND TUNNELS (EXISTING OR UNDER CONSTRUCTION) Clear Creek Tunnel 12. South Bay Aqueduct 23. Los Angeles Aqueduct 1. Whiskeytown-Keswick 13. Hetch Hetchy Aqueduct 24. South Coast Conduit 2.Tunnel 14. Delta Mendota Canal 25. Colorado River Aqueduct 3. Bella Vista Conduit 15. California Aqueduct 26. San Diego Aqueduct 4.Muletown Conduit 16. Pleasant Valley Canal 27. Coachella Canal 5. -

Bulletin 132-80 the California State Water Project—Current Activities

Department o Water Resource . Bulletin 132-8 The California State Water Project Current Activities ·and Future Management Plans .. October 1980 uey D. Johnson, Edmund G. Brown Jr. Ronald B. Robie ecretary for Resources Governor Director he Resources State of Department of . gency California Water Resources - ,~ -- performance levels corresponding to holder of the water rights. if the project capabilities as facilities are Contra Costa Canal should be relocated developed. Briefly, the levels of along a low-level alignment in the dt'velopmentcomprise: 1) prior to the future, the question of ECCID involve operation of New Melones, 2) after New ment will be considered at that time. Melones is operational but before operation of the Peripheral 'Canal, and SB 200, when implemented, will amend the 3) after the Peripheral Canal is oper California Water Code to include provi ational. sion that issues between the State and the delta water agencies concerning the The SDWA has indicated that the pro rights of users to make use of the posal is unacceptable. In March of waters of the Delta may be resolved by 1980, the Department proposed to reop .arbitration. en negotiation such that any differ- ·ences remaining between the Agency and WATER CONTRACTS MANAGEMENT the Department after September 30 be submitted to arbitration. The SDWA Thirty-one water agencies have entered also rejected that proposal. Before into long-term contracts with the State negotiations resume, SDWA wants to for annual water supplies from the State complete its joint study with WPRS. Water Project. A list of these agen The study concerns the CVP and SWP im cies, along with other information con pacts on south Delta water supplies. -

Nikola P. Prokopovich Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt4199s0f4 No online items Inventory of the Nikola P. Prokopovich Papers Finding aid created by Manuscript Archivist Elizabeth Phillips. Processing of this collection was funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and administered by the Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR), Cataloging Hidden Special Collections and Archives program. Department of Special Collections General Library University of California, Davis Davis, CA 95616-5292 Phone: (530) 752-1621 Fax: Fax: (530) 754-5758 Email: [email protected] © 2011 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Inventory of the Nikola P. D-229 1 Prokopovich Papers Creator: Prokopovich, Nikola P. Title: Nikola P. Prokopovich Papers Date: 1947-1994 Extent: 83 linear feet Abstract: The Nikola P. Prokopovich Papers document United States Bureau of Reclamation geologist Nikola Prokopovich's work on irrigation, land subsidence, and geochemistry in California. The collection includes draft reports and memoranda, published writings, slides, photographs, and two films related to several state-wide water projects. Prokopovich was particularly interested in the engineering geology of the Central Valley Project's canals and dam sites and in the effects of the state water projects on the surrounding landscape. Phyiscal location: Researchers should contact Special Collections to request collections, as many are stored offsite. Repository: University of California, Davis. General Library. Dept. of Special Collections. Davis, California 95616-5292 Collection number: D-229 Language of Material: Collection materials in English Biography Nikola P. Prokopovich (1918-1999) was a California-based geologist for the United States Bureau of Reclamation. He was born in Kiev, Ukraine and came to the United States in 1950. -

Floods, Droughts, and Lawsuits: a Brief History of California Water Policy

1Floods, Droughts, and Lawsuits: A Brief History of California Water Policy MPI/GETTY IMAGES The history of California in the twentieth century is the story of a state inventing itself with water. William L. Kahrl, Water and Power, 1982 California’s water system might have been invented by a Soviet bureaucrat on an LSD trip. Peter Passell, “Economic Scene: Greening California,” New York Times, 1991 California has always faced water management challenges and always will. The state’s arid and semiarid climate, its ambitious and evolving economy, and its continually growing population have combined to make shortages and conflicting demands the norm. Over the past two centuries, California has tried to adapt to these challenges through major changes in water manage- ment. Institutions, laws, and technologies are now radically different from those brought by early settlers coming to California from more humid parts of the United States. These adaptations, and the political, economic, technologic, and social changes that spurred them on, have both alleviated and exacerbated the current conflicts in water management. This chapter summarizes the forces and events that shaped water man- agement in California, leading to today’s complex array of policies, laws, and infrastructure. These legacies form the foundation of California’s contemporary water system and will both guide and constrain the state’s future water choices.1 1. Much of the description in this chapter is derived from Norris Hundley Jr.’s outstanding book, The Great Thirst: Californians and Water: A History (Hundley 2001), Robert Kelley’s seminal history of floods in the Central Valley, Battling the Inland Sea (Kelley 1989), and Donald Pisani’s influential study of the rise of irrigated agriculture in California, From the Family Farm to Agribusiness: The Irrigation Crusade in California (Pisani 1984). -

2. the Legacies of Delta History

2. TheLegaciesofDeltaHistory “You could not step twice into the same river; for other waters are ever flowing on to you.” Heraclitus (540 BC–480 BC) The modern history of the Delta reveals profound geologic and social changes that began with European settlement in the mid-19th century. After 1800, the Delta evolved from a fishing, hunting, and foraging site for Native Americans (primarily Miwok and Wintun tribes), to a transportation network for explorers and settlers, to a major agrarian resource for California, and finally to the hub of the water supply system for San Joaquin Valley agriculture and Southern California cities. Central to these transformations was the conversion of vast areas of tidal wetlands into islands of farmland surrounded by levees. Much like the history of the Florida Everglades (Grunwald, 2006), each transformation was made without the benefit of knowing future needs and uses; collectively these changes have brought the Delta to its current state. Pre-European Delta: Fluctuating Salinity and Lands As originally found by European explorers, nearly 60 percent of the Delta was submerged by daily tides, and spring tides could submerge it entirely.1 Large areas were also subject to seasonal river flooding. Although most of the Delta was a tidal wetland, the water within the interior remained primarily fresh. However, early explorers reported evidence of saltwater intrusion during the summer months in some years (Jackson and Paterson, 1977). Dominant vegetation included tules—marsh plants that live in fresh and brackish water. On higher ground, including the numerous natural levees formed by silt deposits, plant life consisted of coarse grasses; willows; blackberry and wild rose thickets; and galleries of oak, sycamore, alder, walnut, and cottonwood. -

Peripheral Canal

0 THE Volume 5, Number 4 RIPHERAL June 1981 CANAL ENVIRONS, a non-partisan environmental law natural resources newsletter published by King Hall School of Law, and edited by the Environmental Law Society, University of California, Davis. Designation of the employer or other affiliation of the author(s) of any article is given for purposes of identification of the author(s) only. The views expressed herein are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Uni- versity of California, School of Law, Envi- ronmental Law Society, or of any employer or organization with which an author is affiliated. Submission of Comments, Letters to the Editor, and Articles is encouraged. We reserve the right to edit and or print these materials. To the earliest Californians, conservation of water-the lifeblood Editorial Staff of all earth's children-was a sacred trust. Western water law, how- Editor-in-Chief ever, developed from the frontier ethic that whoever claimed some- Michael Endicott thing first owned it. Thus, in the California of 1981, water is treated Senior Editor and exploited as a commodity-a liquid gold. Woody Brooks Water is not scarce in California. Annual average run-off far Content Coordinator exceeds present and estimated future requirements. Unfortunately, George Wailes run-off occurs in winter and spring, when our needs are minimal. Editorial Coordinator Additionally, 70% of the total streamflow occurs north of Sacramento, Barb Malchick while 80% of the consumptive requirements lie farther to the south. California's extensive agricultural industry, which has rerouted large Manager Production amounts of surface water from marshlands to provide water for irriga- Anne Frassetto tion, is currently producing deserts. -

State Water Project Trihalomethane Study - (April 1982

STATE WATER PROJECT TRlHALOMETHANE STUDY /- Central District April 1982 · ., FOREWORD Trihalamethanes, ar THMs, are patential cancer causing chemicals farmed in drinking water when certain substances in the water react with chlarine during water treatment.. The primary materials that react to. farm THMs come fram decaying plants and arganic sails. Chlarafarm is the mast·camman type af TBM faund in municipal water supplies~ Cancern aver the widespread accurrence af TBMs in drinking water supplies has recently led to. Federal regulatians limiting their allawable cancentratians. Stud.ies by the Califarnia Department af Health Services, the Metropalitan Water District af Sauthern California, and ather agencies have pravided evidence that water taken fram the sauthern Sacramenta-San Jaaquin Delta is higher in TBM-forming agents than is water fram upstream of the Delta. Treated drinking water fram the southern Delta generally fails to meet the new drinking water standard~ As a result, agencies supplying drinking water fram this saurce are faced with the possible requirement to pravide ' additional castly treatment far TBM removal. The purposes of the State Water Project Trihalomethane Study were to investigate the sources of TBM-forming agents in the State Water Project and to evaluate potential means of reducing their concentrations. In particular, the propased Peripheral Canal was evaluated in terms of its effects in reducing cancentratians of these agents. The study concluded that aperation of the Peripheral Canal would significantly reduce the levels of THMs in the water supplies of Alameda; Contra Costa, and Santa Clara Counties, and Southern California. ~~~C~~ Chief, Central District iii CONTENTS FOREWORD iii ORGANIZATION . -

Draft Environmental Impact Report Peripheral Canal Project

SUMMARY OF DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT REPORT PERIPHERAL CANAL PROJECT State of California THE RESOURCES AGENCY DEPARTMENT OF WATER RESOURCES AUGUST 1974 03.J L/ In this secluded slough of the Delta Meadows Area, some of the characteristics of the early Delta ore still evident. FOREWORV The Calioonnia Vepantment on Waten Re-0ounce-0 (VWR) pnopo-0e-0 to conJtnuct the Peniphenal Canal a-0 an integnal 6eatune on the Calioonnia State Waten Pnoject (SWP). The canal would be a majon link o0 the authonized State Waten P~oject. It i-0 planned a-0 a joint-uJe oacility on the SWP and the 0edenal Centnal Valley Pnoject (CVP). It i-0 needed by 1980, to convey waten acno-0-0 the Sacnamento-San Joaquin Velta to the aqueducu on the SWP and CVP without undue neduction in Jupply on detenionation in quality, to connect centain advenJe envi~onmental condition-0 in the Velta, and to 6acilitate waten management in the Velta. A pnognam o0 -0taged conJtnuction by the State i-0 planned unden which 0edenal panticipation would be 0ea-0ible at any time. Thi-0 bnieo -0ummany on highlight-0 06 the Vnaot Envinonmental Impact Repont (EIR) 0on the Peniphenal Canal Wa-0 compiled with a-0-0i-0tance onom the oinm 06 Jone-0 and Stoke-0 A-0-0ociate-0, Inc., unden contnact to VWR, 0nom detailed matenial contained in the null Vna 0t EIR on the pnoject. It i-0 publi-0hed both a-0 an integnal pant 06 the null nepont and unden -0epanate coven. A-0 a pant Oo the null nepont, it i-0 intended to give the ~eade~ an ovenview and -0ummany o0 the null nepont. -

Public Law 89-561 Be It Ernacted Hy the Senate and House Of

80 STAT. ] PUBLIC LAW 89-561-SEPT. 7, 1966 707 Public Law 89-561 AN ACT September 7, 1966 To authorize the Secretary of the Interior to engage in feasibility investigations '. of certain water resource development proposals. Be it ernacted hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the Water resource United States of America in Congress assembled, That the Secretary development pro- of the Interior is hereby authorized— posaisr feasibii (a) to perform such additional analysis and studies as may ^'y investigations be required on the following proposals which are pending before the Congress : Region 1 Chief Joseph Dam project, Chelan division, Manson unit, along Lake Chelan in north-central Washington; Columbia Basin project, third powerplant, on the Columbia River at Grand Coulee Dam in Washington; Rogue River Basin project. Merlin division, on Jumpoff Joe Creek, a tributary of the Rogue River, in southwestern Oregon; Tualatin project, first phase, on the Tualatin River, near the city of Portland, Oregon; Walla Walla project, Touchet division, on the Touchet River in southeastern Washington; Yakima project, Kennewick division extension, near the mouth of the Yakima River in south-central Washington. Region 3 Lower Colorado River Basin project, in the Low^er Colorado River Basin in Arizona, California, New Mexico, Nevada, and Utah. Region 5 Canton project on the Canadian River below the existing Canton Reservoir in northwestern Oklahoma; Columbus Bend project on the Lower Colorado River Basin in Texas; Palmetto Bend project on the Lavaca and Navidad Rivers in Texas. Region 7 Missouri River Basin project, Midstate division, on the north side of the Platte River in central Nebraska; Missouri River Basin project. -

Trash Control Structures and Equipment: Literature Review And

TRASHCONTROLSTRUCTURESAND EQUIPMENT: A LITERATURE REVIEW ANDSURVEYOFBUREAUOF RECLAMATION EXPERIENCE February 1992 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Bureau of Reclamation Denver Off ice Research and Laboratory Services Division Hydraulics Branch . -"-- ,---, Bureau of Reclamation :PORT STANDARD TITLE PAGl 3. RECIPIENT'S CATALOG NO. 4. TITLEAND SUBTITLE PORT DA TRASH CONTROLSTRUCTURESAND 5. February T692 EQUIPMENT: A LITERATURE REVIEW r 6. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION CODE AND SURVEY OF BUREAU OF RECLAMATION EXPERIENCE 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NO. I Tony L. Wahl R-92-05 I 9. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME AND ADDRESS I 10. WORK UNIT NO. Bureau of Reclamation 11. CONTRACT OR GRANT NO. Denver Office Denver CO 80225 13. TYPE OF REPORT AND PERIOD L COVERED 12. SPONSORING AGENCY NAME AND ADDRESS 14. SPONSORING AGENCY CODE DlBR I Microfiche and hard copy available at the Denver Office, Denver, Colorado. 16. ABSTRACT The Bureau of Reclamation recently initiated research project NM022, Research and Development for Better Trash Screening and Cleaning Devices, as part of the WATER (Water Technology and Environmental Research) program. This report summarizes the results of initial investigations conducted in this research project, including a literature review, a survey of field problems encountered by Regional and Project offices, and site visits to several locations experiencing problems. This report discusses recent innovations in trashrack, trash screen, and trash rake technology, and makes recommendations for further investigations to be conducted under this research-project. 17. KEY WORDS AND DOCUMENT ANALYSIS a. trashrackd trash screensl trash rakes1 fish screensl aquatic weeds1 ice1 sediment 1 b IDENTIFIERS-- Central Arizona Pmjectl San Luis Valley Project1 mechanical trash rakes ( c. -

Cvp Delta Division D3

Delta Division Central Valley Project Eric A. Stene Bureau of Reclamation 1994 Table of Contents The Delta Division--Central Valley Project .........................................2 Project Location.........................................................2 Historic Setting .........................................................3 Project Authorization.....................................................6 Construction History .....................................................7 Division Operation.................................................7 Contra Costa Canal ................................................7 Table I ..........................................................8 Delta-Mendota Canal ..............................................13 Table II.........................................................14 Tracy Pumping Plant..............................................17 Delta Cross Channel ..............................................18 Contra Loma Dam................................................19 Post Construction History ................................................20 Settlement of the Project .................................................23 Uses of Project Water ...................................................24 Conclusion............................................................25 Suggested Readings ...........................................................25 About the Author .............................................................25 Table III....................................................................27 -

The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta and the Political Economy of California Water Allocation

The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta and the Political Economy of California Water Allocation RACHAEL E. GOODHUE Professor of Agricultural and Resource Economics, University of California, Berkeley SUSAN STRATTON SAYRE Assistant Professor of Economics, Smith College LEO K. SIMON Professor of Agricultural and Resource Economics, University of California, Berkeley Independent Institute Working Paper Number 75 September 22, 2010 100 Swan Way, Oakland, CA 94621-1428 • 510-632-1366 • Fax: 510-568-6040 • Email: [email protected] • http://www.independent.org (This is a chapter from the forthcoming book Aquanomics: Water Markets, Bureaucracy, and the Environment, edited by B. Delworth Gardner and Randy T. Simmons) The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta and the Political Economy of California Water Allocation Rachael E. Goodhue, Susan Stratton Sayre, and Leo K. Simon Introduction Large-scale water problems of the nature discussed in this book are inherently difficult to solve. Water distribution and use decisions must be made within a complex system with economic, political, engineering, legal, and ecological dimensions. Any policy choice will impact all of these dimensions. Two critical tasks in the resolution of such debates are to characterize these multi-dimensional impacts for each potential solution and to identify instruments capable of implementing particular choices. Because of the system’s complexity, however, it is virtually inevitable that stakeholders’ interests will conflict under any chosen policy path. These conflicts would be relatively manageable in a world in which (a) property rights were fully defined, (b) benchmarks were available and generally accepted as bases for interpersonal welfare comparisons, and (c) interpersonal compensation was feasible. In such a world, the logical approach would be to choose the policy that maximized aggregate welfare, thus ensuring economically efficient outcomes.