Native Pollinator Conservation at Rauscher Farm: Project Report ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

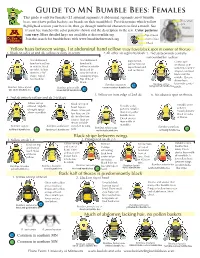

Guide to MN Bumble Bees: Females

Guide to MN Bumble Bees: Females This guide is only for females (12 antennal segments, 6 abdominal segments, most bumble Three small bees, most have pollen baskets, no beards on their mandibles). First determine which yellow eyes highlighted section your bee is in, then go through numbered characters to find a match. See if your bee matches the color patterns shown and the description in the text. Color patterns ® can vary. More detailed keys are available at discoverlife.org. Top of head Bee Front of face Squad Join the search for bumble bees with www.bumbleebeewatch.org Cheek Yellow hairs between wings, 1st abdominal band yellow (may have black spot in center of thorax) 1. Black on sides of 2nd ab, yellow or rusty in center 2.All other ab segments black 3. 2nd ab brownish centrally surrounded by yellow 2nd abdominal 2nd abdominal Light lemon Center spot band with yellow band with yellow hairs on on thorax with in middle, black yellow in middle top of head and sometimes faint V on sides. Yellow bordered by and on thorax. shaped extension often in a “W” rusty brown in a back from the shape. Top of swooping shape. middle. Queens head yellow. Top of head do not have black. Bombus impatiens Bombus affinis brownish central rusty patched bumble bee Bombus bimaculatus Bombus griseocollis common eastern bumble bee C patch. two-spotted bumble bee C brown-belted bumble bee C 5. Yellow on front edge of 2nd ab 6. No obvious spot on thorax. 4. 2nd ab entirely yellow and ab 3-6 black Yellow on top Black on top of Variable color of head. -

Bumble Bees of CT-Females

Guide to CT Bumble Bees: Females This guide is only for females (12 antennal segments, 6 abdominal segments, most bumble bees, most have pollen baskets, no beards on their mandibles). First determine which yellow Three small eyes highlighted section your bee is in, then go through numbered characters to find a match. See if your bee matches the color patterns shown and the description in the text. Color patterns can vary. More detailed keys are available at discoverlife.org. Top of head Join the search for bumble bees with www.bumbleebeewatch.org Front of face Cheek Yellow hairs between wings, 1st abdominal band yellow (may have black spot in center of thorax) 1. Black on sides of 2nd ab, yellow or rusty in center 2.All other ab segments black 3. 2nd ab brownish centrally surrounded by yellow 2nd abdominal 2nd abdominal Light lemon Center spot band with yellow band with yellow hairs on on thorax with in middle, black yellow in middle top of head and sometimes faint V on sides. Yellow bordered by and on thorax. shaped extension often in a “W” rusty brown in a back from the shape. Top of swooping shape. middle. Queens head yellow. Top of head do not have black. Bombus impatiens Bombus affinis brownish central rusty patched bumble bee Bombus bimaculatus Bombus griseocollis common eastern bumble bee patch. two-spotted bumble bee brown-belted bumble bee 4. 2nd ab entirely yellow and ab 3-6 black 5. No obvious spot on thorax. Yellow on top Black on top of Variable color of head. -

Assessing Bumble Bee Diversity, Distribution, and Status for the Michigan Wildlife Action Plan

Assessing Bumble Bee Diversity, Distribution, and Status for the Michigan Wildlife Action Plan Prepared By: Logan M. Rowe, David L. Cuthrell, and Helen D. Enander Michigan Natural Features Inventory Michigan State University Extension P.O. Box 13036 Lansing, MI 48901 Prepared For: Michigan Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Division 12/17/2019 MNFI Report No. 2019-33 Suggested Citation: Rowe, L. M., D. L. Cuthrell., H. D. Enander. 2019. Assessing Bumble Bee Diversity, Distribution, and Status for the Michigan Wildlife Action Plan. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report Number 2019- 33, Lansing, USA. Copyright 2019 Michigan State University Board of Trustees. MSU Extension programs and materials are open to all without regard to race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, marital status or family status. Cover: Bombus terricola taken by D. L. Cuthrell Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................................................ iii Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Methods ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 Museum Searches .................................................................................................................................... -

Bumble Bees of Virginia

Many bumble bees WHAT CAN YOU DO? VIRGINIA WORKING LANDSCAPES are in decline. Plant native plants! Bumble bees need a stable source of nectar and pollen throughout the growing season, so plant a B u m b l e B e e s suite of native flowers that bloom from early spring to fall. Native plants are recommended because they are beneficial to other insects and wildlife as well. For tips on gardening with native plants, visit the of Virginia Virginia Native Plant Society’s website at: www.vnps.org Bombus impatiens colony, T’ai Roulston Reduce or stop using pesticides! If you use pesticides, visit www.xerces.org to learn Bumble bees are invaluable pollinators. We which chemicals are the most toxic to bees and rely on them to pollinate our fruits, vegetables, how and when to apply pesticides in order to and thousands of native plant species. minimize impacts to bees. Many of our North American bumble bees are Protect the nest! experiencing steep population declines. For Bumble bees nest in the ground during the summer example, the once common Bombus affinis, the and queens overwinter just an inch or two below the rusty-patched bumble bee, has declined by soil’s surface. If you see an area of your yard with a lot of bee activity, do not disturb it if possible. Post- roughly 80% and is only found in isolated areas pone tilling and other soil disturbance practices in within its historic range. Threats to bumble this area in the early spring to allow queens to bees include parasites, disease, habitat loss, emerge. -

Golden Northern Bumble Bee Bombus Fervidus ILLINOIS RANGE

golden northern bumble bee Bombus fervidus Kingdom: Animalia FEATURES Phylum: Arthropoda Coloration is somewhat variable. Color in the Class: Insecta descriptions refers to “hair” color. “Hair” is of Order: Hymenoptera medium length. The face is black. The thorax and the first four abdominal segments are mainly yellow. Family: Apidae There is usually a black band between the base of ILLINOIS STATUS the wings. The fifth abdominal segment is black. Wings are clear with black veins. uncommon, native BEHAVIORS These insects are long-tongued bees that are found in open fields and meadows. They are often seen at honeysuckles (Lonicera spp.), thistles (Cirsium spp.), clovers (Trifolium spp.), beardstongues (Penstemon spp.), loosestrifes (Lythrum spp.), vetches (Vicia spp.) and bee balms (Monarda spp.). They are important pollinators of the flowers that they visit to collect nectar and pollen. They are eusocial insects. They nest on or under the surface of the ground. Their life cycle includes egg, larva, pupa and adult stages. Only the fertilized queen overwinters from a colony. In the spring, she selects a nest site and constructs the nest, which is lined with plant materials. The first brood raised consists of all workers (females). The workers do all the jobs of the hive except egg-laying. Late in the year both males and queens ILLINOIS RANGE are produced. Males mate with queens in the fall. © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2021. Biodiversity of Illinois. Unless otherwise noted, photos and images © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. © Rob Curtis / The Early Birder Aquatic Habitats marshes; peatlands; wet prairies and fens Woodland Habitats none Prairie and Edge Habitats black soil prairie; dolomite prairie; edge; gravel prairie; hill prairie; sand prairie; shrub prairie © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. -

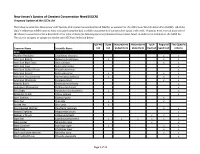

NJ List of Species of Greatest Conservation Need

New Jersey's Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) Proposed Update of the SGCN List The following table lists New Jersey's 657 Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN), as updated for the 2015 State Wildlife Action Plan (SWAP). All of the state's indigenous wildlife species were evaluated using the best available assessments of conservation status and trends. A species must meet at least one of the chosen assessment criteria described in the table, Criteria for Selecting Species of Greatest Conservation Need , in order to be included on the SGCN list. The criteria category or categories met by each SGCN are indicated below. USFWS State NatureServe NatureServe IUCN Regional Taxa Specific Common Name Scientific Name List List Global Rank State Rank Red List SGCN List Criteria Birds Acadian Flycatcher Empidonax virescens x x American Bittern Botaurus lentiginosus x x x American Black Duck Anas rubripes x x American Coot Fulica americana x American Golden Plover Pluvialis dominica x American Kestrel Falco sparverius x x x American Oystercatcher Haematopus palliatus x x x American Woodcock Scolopax minor x x Atlantic Brant Branta bernicla hrota x Audubon's Shearwater Puffinus iherminieri x Bald Eagle Haliaeetus leucocephalus x x Baltimore Oriole Icterus galbula x Bank Swallow Riparia riparia x Barn Owl Tyto alba x x Barred Owl Strix varia x Bay-breasted Warbler Dendroica castanea x x Belted Kingfisher Megaceryle alcyon x Bicknell's Thrush Catharus bicknelli x x x Black Rail Laterallus jamaicensis x x x x x x Black Scoter Melanitta -

Bumble Bees of Arkansas (Hymenoptera, Apidae, Bombinae) Leland Chandler Purdue University

Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science Volume 19 Article 11 1965 Bumble Bees of Arkansas (Hymenoptera, Apidae, Bombinae) Leland Chandler Purdue University C. Edward McCoy Jr. University of Arkansas Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas Part of the Entomology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Chandler, Leland and McCoy, C. Edward Jr. (1965) "Bumble Bees of Arkansas (Hymenoptera, Apidae, Bombinae)," Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science: Vol. 19 , Article 11. Available at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol19/iss1/11 This article is available for use under the Creative Commons license: Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-ND 4.0). Users are able to read, download, copy, print, distribute, search, link to the full texts of these articles, or use them for any other lawful purpose, without asking prior permission from the publisher or the author. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science, Vol. 19 [1965], Art. 11 46 Arkansas Academy of Science Proceedings, Vol. 19, 1965 THE BUMBLE BEES OF ARKANSAS (HYMENOPTERA, APIDAE, BOMBINAE) Leland Chandler and C. Edward McCoy, Jr. Departments of Entomology, Purdue University & University of Arkansas, respectively. PREFACE The Department of Entomology, University of Arkansas, undertook a visiting scientist program during the summer of 1964. The major objective of this program was to further the development of a bio- systematic program which would contribute to the many facets of ento- mological research and teaching. -

Pollinator Management Guide

Chase M. Wasicuna Land and Water Management Assiniboine Community College, City of Brandon April 3, 2017 Acknowledgments This Management Guide was designed in partnership with and assistance from: - The City of Brandon - Lindsay Hargreaves, City of Brandon - Sherry Punak-Murphy, CFB Shilo - Melanie Dubois, Agriculture and Agri-food Canada, Manitoba - Mark Wonneck, Agriculture and Agri-food Canada, Alberta - Neal Hackler, Assiniboine Community College I would like to thank everyone who helped provide information and input for the development of this guide. Annotated Bibliography The decline of bees has begun to gain recognition; however, the general public does not recognise the level of decline in native pollinators. “There hasn't been a lot of attention paid to native bees, which include well-known bumblebees and lesser-known varieties such as leafcutting bees or orchard mason bees.” Dyson (2016). Raising awareness of the local native species is a key part to developing an inclusive pollinator program. Not all pollinators are easily recognizable like the many species of bumblebees, but even if you don’t see them they are still an important part of the food production “…since bees pollinate 75 percent of fruits, nuts, and vegetables grown in North America.” Weidenhammer (2016). In order to maintain a healthy pollinator population in any location you must have the resources available for them. Pollinators require food, nesting sites, water, and a safe area that will enable them to live in peace. Providing the resources need for pollinator populations doesn’t require as much maintenance as one might imagine. For a program such as this it is the small actions that make the biggest difference, “Plant natives… in your yards, and native flowers in corner lots and at the edges of crop fields… get bee homes… Small actions make a difference when it comes to helping pollinators.” Krakos (2015). -

Suckley's Cuckoo Bumblebee Listing Petition

BEFORE THE SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR PETITION TO LIST SUCKLEY’S CUCKOO BUMBLE BEE (Bombus suckleyi) UNDER THE ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT AND CONCURRENTLY DESIGNATE CRITICAL HABITAT Suckley’s cuckoo bumble bee Hadel Go, AMNH CC BY-NC 3.0 US CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY April 23, 2020 NOTICE OF PETITION David Bernhardt, Secretary U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Margaret Everson, Principal Deputy Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Gary Frazer, Assistant Director for Endangered Species U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1840 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Robyn Thorson, Regional Director Region 1 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 911 NE 11th Ave. Portland, OR 97232-4181 [email protected] Anna Munoz, Assistant Regional Director Region 6 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 134 Union Boulevard, Suite 650 Lakewood, CO 80228 [email protected] Paul Souza, Regional Director Region 8 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2800 Cottage Way, Suite W2606 Sacramento, California 95825 [email protected] ii Pursuant to Section 4(b) of the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”), 16 U.S.C. § 1533(b); Section 553(e) of the Administrative Procedure Act, 5 U.S.C. § 553(e); and 50 C.F.R. § 424.14(a), the Center for Biological Diversity hereby petitions the Secretary of the Interior, through the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (“FWS,” “Service”), to protect Suckley’s cuckoo bumble bee (Bombus suckleyi) under the ESA. -

Guide to Bumble Bees of the Western United States

Bumble Bees of the Western United States By Jonathan Koch James Strange A product of the U.S. Forest Service and the Pollinator Partnership Paul Williams with funding from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation Executive Editor Larry Stritch, Ph.D., USDA Forest Service Cover: Bombus huntii foraging. Photo Leah Lewis Executive and Managing Editor Laurie Davies Adams, The Pollinator Partnership Graphic Design and Art Direction Marguerite Meyer Administration Jennifer Tsang, The Pollinator Partnership IT Production Support Elizabeth Sellers, USGS Alphabetical Quick Reference to Species B. appositus .............110 B. frigidus ..................46 B. rufocinctus ............86 B. balteatus ................22 B. griseocollis ............90 B. sitkensis ................38 B. bifarius ..................78 B. huntii ....................66 B. suckleyi ...............134 B. californicus ..........114 B. insularis ...............126 B. sylvicola .................70 B. caliginosus .............26 B. melanopygus .........62 B. ternarius ................54 B. centralis ................34 B. mixtus ...................58 B. terricola ...............106 B. crotchii ..................82 B. morrisoni ...............94 B. vagans ...................50 B. fernaldae .............130 B. nevadensis .............18 B. vandykei ................30 B. fervidus................118 B. occidentalis .........102 B. vosnesenskii ..........74 B. flavifrons ...............42 B. pensylvanicus subsp. sonorus ....122 B. franklini .................98 2 Bumble Bees of the -

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Animal Species of North Carolina 2020

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Animal Species of North Carolina 2020 Hickory Nut Gorge Green Salamander (Aneides caryaensis) Photo by Austin Patton 2014 Compiled by Judith Ratcliffe, Zoologist North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources www.ncnhp.org C ur Alleghany rit Ashe Northampton Gates C uc Surry am k Stokes P d Rockingham Caswell Person Vance Warren a e P s n Hertford e qu Chowan r Granville q ot ui a Mountains Watauga Halifax m nk an Wilkes Yadkin s Mitchell Avery Forsyth Orange Guilford Franklin Bertie Alamance Durham Nash Yancey Alexander Madison Caldwell Davie Edgecombe Washington Tyrrell Iredell Martin Dare Burke Davidson Wake McDowell Randolph Chatham Wilson Buncombe Catawba Rowan Beaufort Haywood Pitt Swain Hyde Lee Lincoln Greene Rutherford Johnston Graham Henderson Jackson Cabarrus Montgomery Harnett Cleveland Wayne Polk Gaston Stanly Cherokee Macon Transylvania Lenoir Mecklenburg Moore Clay Pamlico Hoke Union d Cumberland Jones Anson on Sampson hm Duplin ic Craven Piedmont R nd tla Onslow Carteret co S Robeson Bladen Pender Sandhills Columbus New Hanover Tidewater Coastal Plain Brunswick THE COUNTIES AND PHYSIOGRAPHIC PROVINCES OF NORTH CAROLINA Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Animal Species of North Carolina 2020 Compiled by Judith Ratcliffe, Zoologist North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org This list is dynamic and is revised frequently as new data become available. New species are added to the list, and others are dropped from the list as appropriate. The list is published periodically, generally every two years. -

Avian Diet and Visual Perception Suggests Avian Predation Selects for Color Pattern Mimicry in Bumble Bees

AVIAN DIET AND VISUAL PERCEPTION SUGGESTS AVIAN PREDATION SELECTS FOR COLOR PATTERN MIMICRY IN BUMBLE BEES BY JOHN M. MADDUX THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Entomology in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2015 Urbana, Illinois Master’s Committee: Professor Sydney A. Cameron, Chair, Director of Research Professor Andrew V. Suarez Assistant Professor Michael P. Ward ABSTRACT Mimicry theory was developed by H. W. Bates and F. Müller based on their observations of similarities among butterflies, and since publication their theories have been used to explain numerous other mimicry systems. Bumble bees can be found in throughout the temperate parts of the word, as well as the high mountains and polar regions. In any given area, the local bumble bee species tend to share the same color patterns. Statistical confirmation of these trends has resulted in the hypothesis that these similarity groups are Müllerian mimicry rings. Bumble bee color patterns are thought to convey protection from avian predators, thus creating selection for fewer, more effective color patterns. Evidence for birds as predators of bumble bees primarily comprises logical arguments bolstered by only a few laboratory studies and empirical accounts. Although the hypothesis that birds are bumble bee predators driving the evolution of Müllerian mimicry is well reasoned and has some evidential support, strong experimental data are lacking. To test the effects of bumble bee color pattern on avian attack frequency, I created bumble bee models from soft plasticine with local, novel, and non-aposematic color patterns.