Avian Diet and Visual Perception Suggests Avian Predation Selects for Color Pattern Mimicry in Bumble Bees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(DLR): an Undescribed Behavior in Bumble Bees

The disturbance leg-lift response (DLR): an undescribed behavior in bumble bees Christopher A. Varnon, Noelle Vallely, Charlie Beheler and Claudia Coffin Department of Psychology, Converse College, Spartanburg, SC, United States of America ABSTRACT Background. Bumble bees, primarily Bombus impatiens and B. terrestris, are becoming increasingly popular organisms in behavioral ecology and comparative psychology research. Despite growing use in foraging and appetitive conditioning experiments, little attention has been given to innate antipredator responses and their ability to be altered by experience. In this paper, we discuss a primarily undescribed behavior, the disturbance leg-lift response (DLR). When exposed to a presumably threatening stimulus, bumble bees often react by lifting one or multiple legs. We investigated DLR across two experiments. Methods. In our first experiment, we investigated the function of DLR as a prerequisite to later conditioning research. We recorded the occurrence and sequence of DLR, biting and stinging in response to an approaching object that was either presented inside a small, clear apparatus containing a bee, or presented directly outside of the subject's apparatus. In our second experiment, we investigated if DLR could be altered by learning and experience in a similar manner to many other well-known bee behaviors. We specifically investigated habituation learning by repeatedly presenting a mild visual stimulus to samples of captive and wild bees. Results. The results of our first experiment show that DLR and other defensive behaviors occur as a looming object approaches, and that the response is greater when proximity to the object is lower. More importantly, we found that DLR usually occurs first, rarely precedes biting, and often precedes stinging. -

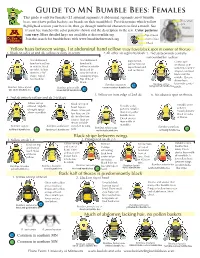

Guide to MN Bumble Bees: Females

Guide to MN Bumble Bees: Females This guide is only for females (12 antennal segments, 6 abdominal segments, most bumble Three small bees, most have pollen baskets, no beards on their mandibles). First determine which yellow eyes highlighted section your bee is in, then go through numbered characters to find a match. See if your bee matches the color patterns shown and the description in the text. Color patterns ® can vary. More detailed keys are available at discoverlife.org. Top of head Bee Front of face Squad Join the search for bumble bees with www.bumbleebeewatch.org Cheek Yellow hairs between wings, 1st abdominal band yellow (may have black spot in center of thorax) 1. Black on sides of 2nd ab, yellow or rusty in center 2.All other ab segments black 3. 2nd ab brownish centrally surrounded by yellow 2nd abdominal 2nd abdominal Light lemon Center spot band with yellow band with yellow hairs on on thorax with in middle, black yellow in middle top of head and sometimes faint V on sides. Yellow bordered by and on thorax. shaped extension often in a “W” rusty brown in a back from the shape. Top of swooping shape. middle. Queens head yellow. Top of head do not have black. Bombus impatiens Bombus affinis brownish central rusty patched bumble bee Bombus bimaculatus Bombus griseocollis common eastern bumble bee C patch. two-spotted bumble bee C brown-belted bumble bee C 5. Yellow on front edge of 2nd ab 6. No obvious spot on thorax. 4. 2nd ab entirely yellow and ab 3-6 black Yellow on top Black on top of Variable color of head. -

The Conservation Management and Ecology of Northeastern North

THE CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT AND ECOLOGY OF NORTHEASTERN NORTH AMERICAN BUMBLE BEES AMANDA LICZNER A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN BIOLOGY YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO September 2020 © Amanda Liczner, 2020 ii Abstract Bumble bees (Bombus spp.; Apidae) are among the pollinators most in decline globally with a main cause being habitat loss. Habitat requirements for bumble bees are poorly understood presenting a research gap. The purpose of my dissertation is to characterize the habitat of bumble bees at different spatial scales using: a systematic literature review of bumble bee nesting and overwintering habitat globally (Chapter 1); surveys of local and landcover variables for two at-risk bumble bee species (Bombus terricola, and B. pensylvanicus) in southern Ontario (Chapter 2); identification of conservation priority areas for bumble bee species in Canada (Chapter 3); and an analysis of the methodology for locating bumble bee nests using detection dogs (Chapter 4). The main findings were current literature on bumble bee nesting and overwintering habitat is limited and biased towards the United Kingdom and agricultural habitats (Ch.1). Bumble bees overwinter underground, often on shaded banks or near trees. Nests were mostly underground and found in many landscapes (Ch.1). B. terricola and B. pensylvanicus have distinct habitat characteristics (Ch.2). Landscape predictors explained more variation in the species data than local or floral resources (Ch.2). Among local variables, floral resources were consistently important throughout the season (Ch.2). Most bumble bee conservation priority areas are in western Canada, southern Ontario, southern Quebec and across the Maritimes and are most often located within woody savannas (Ch.3). -

Bumble Bees of CT-Females

Guide to CT Bumble Bees: Females This guide is only for females (12 antennal segments, 6 abdominal segments, most bumble bees, most have pollen baskets, no beards on their mandibles). First determine which yellow Three small eyes highlighted section your bee is in, then go through numbered characters to find a match. See if your bee matches the color patterns shown and the description in the text. Color patterns can vary. More detailed keys are available at discoverlife.org. Top of head Join the search for bumble bees with www.bumbleebeewatch.org Front of face Cheek Yellow hairs between wings, 1st abdominal band yellow (may have black spot in center of thorax) 1. Black on sides of 2nd ab, yellow or rusty in center 2.All other ab segments black 3. 2nd ab brownish centrally surrounded by yellow 2nd abdominal 2nd abdominal Light lemon Center spot band with yellow band with yellow hairs on on thorax with in middle, black yellow in middle top of head and sometimes faint V on sides. Yellow bordered by and on thorax. shaped extension often in a “W” rusty brown in a back from the shape. Top of swooping shape. middle. Queens head yellow. Top of head do not have black. Bombus impatiens Bombus affinis brownish central rusty patched bumble bee Bombus bimaculatus Bombus griseocollis common eastern bumble bee patch. two-spotted bumble bee brown-belted bumble bee 4. 2nd ab entirely yellow and ab 3-6 black 5. No obvious spot on thorax. Yellow on top Black on top of Variable color of head. -

State Attorney Will Not Charge Man Who Shot, Killed 17-Year-Old During Burglary

WEEKEND: SEPT. 6-8, 2020 FLORIDA LEAGUE AWARDS NO NEED TO FEAR Diego Garcia of the DeLand Seminole County Master Suns wins David Eckstein Gardener talks about Sportsmanship Award Wasp Mimics See Sports, Page 8 See People, Page 5 SANFORD HERALD LAKE MARY, LONGWOOD, WINTER SPRINGS, OVIEDO, GENEVA, CASSELBERRY, OSTEEN, CHULUOTA, ALTAMONTE SPRINGS, DEBARY Vol. 130, No. 9 • © 2020 READ US ONLINE AT: MYSANFORDHERALD.COM Since 1908 HEADLINES FROM Sanford CRA approves funding to renovate Superintendent Walt Griffin ASSOCIATED PRESS announces retirement Your daily look at late-breaking Welcome Center into Information Center news, upcoming events and the sto- By Steve Paradis ries that will be talked about today: By Steve Paradis Herald Staff Herald Staff BIDEN TO TEST PROMISE TO Dr. Walt Griffin, superintendent of Seminole UNIFY NATION The Sanford Community Re- County Public Schools, has announced his re- development Agency voted tirement after 40 years as an educator, 37 of The Democrat travels to unanimously to enter into two which were served in Kenosha, Wisconsin — a city agreements to change the His- Seminole County. wrenched by police and protest toric Sanford Welcome Center For now, the plan is for violence — where he believes he into the new Sanford Informa- Griffin to finish out the can help community leaders find tion Center. Members also ap- school year, but a superin- common ground. proved spending $12,000 for the tendent search will begin digital marketing of Sanfording next week, said Michael VIDEO: ROCHESTER POLICE Safely. Lawrence, district commu- DEATH FEATURED HOOD On June 8, the Sanford City nication officer. If someone Commission approved $30,000 is found, then Griffin will A Black man who had run toward renovation of the build- naked through the streets of a ing into a new business center Dr. -

Assessing Bumble Bee Diversity, Distribution, and Status for the Michigan Wildlife Action Plan

Assessing Bumble Bee Diversity, Distribution, and Status for the Michigan Wildlife Action Plan Prepared By: Logan M. Rowe, David L. Cuthrell, and Helen D. Enander Michigan Natural Features Inventory Michigan State University Extension P.O. Box 13036 Lansing, MI 48901 Prepared For: Michigan Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Division 12/17/2019 MNFI Report No. 2019-33 Suggested Citation: Rowe, L. M., D. L. Cuthrell., H. D. Enander. 2019. Assessing Bumble Bee Diversity, Distribution, and Status for the Michigan Wildlife Action Plan. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report Number 2019- 33, Lansing, USA. Copyright 2019 Michigan State University Board of Trustees. MSU Extension programs and materials are open to all without regard to race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, marital status or family status. Cover: Bombus terricola taken by D. L. Cuthrell Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................................................ iii Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Methods ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 Museum Searches .................................................................................................................................... -

Plos ONE 10(5): E0125847

RESEARCH ARTICLE Hitting an Unintended Target: Phylogeography of Bombus brasiliensis Lepeletier, 1836 and the First New Brazilian Bumblebee Species in a Century (Hymenoptera: Apidae) José Eustáquio Santos Júnior1, Fabrício R. Santos1, Fernando A. Silveira2* 1 Departamento de Biologia Geral, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil, 2 Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil * [email protected] OPEN ACCESS Abstract Citation: Santos Júnior JE, Santos FR, Silveira FA (2015) Hitting an Unintended Target: Phylogeography This work tested whether or not populations of Bombus brasiliensis isolated on mountain of Bombus brasiliensis Lepeletier, 1836 and the First tops of southeastern Brazil belonged to the same species as populations widespread in low- New Brazilian Bumblebee Species in a Century (Hymenoptera: Apidae). PLoS ONE 10(5): e0125847. land areas in the Atlantic coast and westward along the Paraná-river valley. Phylogeo- doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0125847 graphic and population genetic analyses showed that those populations were all Academic Editor: Sean Brady, Smithsonian National conspecific. However, they revealed a previously unrecognized, apparently rare, and poten- Museum of Natural History, UNITED STATES tially endangered species in one of the most threatened biodiversity hotspots of the World, Received: September 18, 2014 the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. This species is described here as Bombus bahiensis sp. n., and included in a revised key for the identification of the bumblebee species known to occur Accepted: March 25, 2015 in Brazil. Phylogenetic analyses based on two mtDNA markers suggest this new species to Published: May 20, 2015 be sister to B. -

Creating Economically and Ecologically Sustainable Pollinator Habitat District 2 Demonstration Research Project Summary Updated for Site Visit in April 2019

Creating Economically and Ecologically Sustainable Pollinator Habitat District 2 Demonstration Research Project Summary Updated for Site Visit in April 2019 The PIs are most appreciative for identification assistance provided by: Arian Farid and Alan R. Franck, Director and former Director, resp., University of South Florida Herbarium, Tampa, FL; Edwin Bridges, Botanical and Ecological Consultant; Floyd Griffith, Botanist; and Eugene Wofford, Director, University of Tennessee Herbarium, Knoxville, TN Investigators Rick Johnstone and Robin Haggie (IVM Partners, 501-C-3 non-profit; http://www.ivmpartners.org/); Larry Porter and John Nettles (ret.), District 2 Wildflower Coordinator; Jeff Norcini, FDOT State Wildflower Specialist Cooperator Rick Owen (Imperiled Butterflies of Florida Work Group – North) Objective Evaluate a cost-effective strategy for creating habitat for pollinators/beneficial insects in the ROW beyond the back-slope. Rationale • Will aid FDOT in developing a strategy to create pollinator habitat per the federal BEE Act and FDOT’s Wildflower Program • Will demonstrate that FDOT can simultaneously • Create sustainable pollinator habitat in an economical and ecological manner • Reduce mowing costs • Part of national effort coordinated by IVM Partners, who has • Established or will establish similar projects on roadside or utility ROWS in Alabama, Arkansas, Maryland, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Idaho, Montana, Virginia, West Virginia, and Tennessee; studies previously conducted in Arizona, Delaware, Michigan, and New Jersey • Developed partnerships with US Fish & Wildlife Service, Army Corps of Engineers, US Geological Survey, New Jersey Institute of Technology, Rutgers University, Chesapeake Bay Foundation, Chesapeake Wildlife Heritage, The Navajo Nation, The Wildlife Habitat Council, The Pollinator Partnership, Progressive Solutions, Bayer Crop Sciences, Universities of Maryland, Ohio, West Virginia, and the EPA. -

Bumblebee Conservator

Volume 2, Issue 1: First Half 2014 Bumblebee Conservator Newsletter of the BumbleBee Specialist Group In this issue From the Chair From the Chair 1 A very happy and productive 2014 to everyone! We start this year having seen From the Editor 1 enormously encouraging progress in 2013. Our different regions have started from BBSG Executive Committee 2 very different positions, in terms of established knowledge of their bee faunas Regional Coordinators 2 as well as in terms of resources available, but members in all regions are actively moving forward. In Europe and North America, which have been fortunate to Bumblebee Specialist have the most specialists over the last century, we are achieving the first species Group Report 2013 3 assessments. Mesoamerica and South America are also very close, despite the huge Bumblebees in the News 9 areas to survey and the much less well known species. In Asia, with far more species, many of them poorly known, remarkably rapid progress is being made in sorting Research 13 out what is present and in building the crucial keys and distribution maps. In some Conservation News 20 regions there are very few people to tackle the task, sometimes in situations that Bibliography 21 make progress challenging and slow – their enthusiasm is especially appreciated! At this stage, broad discussion of problems and of the solutions developed from your experience will be especially important. This will direct the best assessments for focusing the future of bumblebee conservation. From the Editor Welcome to the second issue of the Bumblebee Conservator, the official newsletter of the Bumblebee Specialist Group. -

Native Pollinator Conservation at Rauscher Farm: Project Report ______

Native Pollinator Conservation at Rauscher Farm: Project Report ______________________________________________________________________________ Interdisciplinary Qualifying Project This report represents the work of one or more WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of completion of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on the web without editorial or peer review. Worcester Polytechnic Institute Fall 2020 - Spring 2021 By: David Chen Joy Tartaglia 06 May 2021 Professor David I. Spanagel Department of Humanities & Arts 1 Table of Contents Table of Figures 3 Abstract 4 Acknowledgements 5 Executive Summary 6 1. Introduction 8 2. Background 11 2.1 Brief History of Rauscher Farm 11 2.2 Biodiversity and Bees 11 2.2.1 Difference Between Bumblebees and Honey Bees 12 2.2.2 Bombus fervidus and Bombus vagans 13 2.2.2 Bumblebee Lifecycle 14 2.3 Factors Contributing to Pollinator Declines 15 2.3.1 Habitat Loss and Fragmentation 16 2.3.2 Agrochemicals 17 2.3.3 Alien Species and Competition 17 2.3.4 Diseases 18 2.3.5 Climate Change 18 2.3.6 Impacts of Pollinator Declines 19 2.4 Public Awareness and the Beecology Project 19 3. Methodology 22 3.1 Interviews 22 3.1.1 Experts 23 3.1.2 Site Visit 23 3.2 Pollinator Garden 23 3.2.1 Objectives for Pollinator Garden Planning 24 3.2.1.1 Native Pollinators 24 3.2.1.2 Plant Selection 25 3.2.1.3 Location Requirements 25 3.3 Rauscher Farm’s Habitat Maintenance 26 3.4 Methods for Raising Public Awareness 26 4. Results 28 4.1 Ecological Relationships 28 2 4.2 Pollinator Garden Plans 31 4.2.1 Design 31 4.2.2 Plants 32 4.2.3 Location 33 4.2.4 Management 34 4.2.5 Public Awareness 35 5. -

Atlas of Pollen and Plants Used by Bees

AtlasAtlas ofof pollenpollen andand plantsplants usedused byby beesbees Cláudia Inês da Silva Jefferson Nunes Radaeski Mariana Victorino Nicolosi Arena Soraia Girardi Bauermann (organizadores) Atlas of pollen and plants used by bees Cláudia Inês da Silva Jefferson Nunes Radaeski Mariana Victorino Nicolosi Arena Soraia Girardi Bauermann (orgs.) Atlas of pollen and plants used by bees 1st Edition Rio Claro-SP 2020 'DGRV,QWHUQDFLRQDLVGH&DWDORJD©¥RQD3XEOLFD©¥R &,3 /XPRV$VVHVVRULD(GLWRULDO %LEOLRWHF£ULD3ULVFLOD3HQD0DFKDGR&5% $$WODVRISROOHQDQGSODQWVXVHGE\EHHV>UHFXUVR HOHWU¶QLFR@RUJV&O£XGLD,Q¬VGD6LOYD>HW DO@——HG——5LR&ODUR&,6(22 'DGRVHOHWU¶QLFRV SGI ,QFOXLELEOLRJUDILD ,6%12 3DOLQRORJLD&DW£ORJRV$EHOKDV3µOHQ– 0RUIRORJLD(FRORJLD,6LOYD&O£XGLD,Q¬VGD,, 5DGDHVNL-HIIHUVRQ1XQHV,,,$UHQD0DULDQD9LFWRULQR 1LFRORVL,9%DXHUPDQQ6RUDLD*LUDUGL9&RQVXOWRULD ,QWHOLJHQWHHP6HUYL©RV(FRVVLVWHPLFRV &,6( 9,7¯WXOR &'' Las comunidades vegetales son componentes principales de los ecosistemas terrestres de las cuales dependen numerosos grupos de organismos para su supervi- vencia. Entre ellos, las abejas constituyen un eslabón esencial en la polinización de angiospermas que durante millones de años desarrollaron estrategias cada vez más específicas para atraerlas. De esta forma se establece una relación muy fuerte entre am- bos, planta-polinizador, y cuanto mayor es la especialización, tal como sucede en un gran número de especies de orquídeas y cactáceas entre otros grupos, ésta se torna más vulnerable ante cambios ambientales naturales o producidos por el hombre. De esta forma, el estudio de este tipo de interacciones resulta cada vez más importante en vista del incremento de áreas perturbadas o modificadas de manera antrópica en las cuales la fauna y flora queda expuesta a adaptarse a las nuevas condiciones o desaparecer. -

Zootaxa, Pupal Cases of Nearctic Robber Flies (Diptera: Asilidae)

ZOOTAXA 1868 Pupal cases of Nearctic robber flies (Diptera: Asilidae) D. STEVE DENNIS, JEFFREY K. BARNES & LLOYD KNUTSON Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand D. STEVE DENNIS, JEFFREY K. BARNES & LLOYD KNUTSON Pupal cases of Nearctic robber flies (Diptera: Asilidae) (Zootaxa 1868) 98 pp.; 30 cm. 3 Sept. 2008 ISBN 978-1-86977-265-9 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-86977-266-6 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2008 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41-383 Auckland 1346 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ © 2008 Magnolia Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted or disseminated, in any form, or by any means, without prior written permission from the publisher, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed in writing. This authorization does not extend to any other kind of copying, by any means, in any form, and for any purpose other than private research use. ISSN 1175-5326 (Print edition) ISSN 1175-5334 (Online edition) 2 · Zootaxa 1868 © 2008 Magnolia Press DENNIS ET AL. Zootaxa 1868: 1–98 (2008) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2008 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Pupal cases of Nearctic robber flies (Diptera: Asilidae) D. STEVE DENNIS1, JEFFREY K. BARNES2,4 & LLOYD KNUTSON3 11105 Myrtle Wood Drive, St. Augustine, Florida 32086, USA; e-mail: [email protected] 2University of Arkansas, Department of Entomology, 319 Agriculture Building, Fayetteville, Arkansas 72701, USA; e-mail: jbar- [email protected] 3Systematic Entomology Laboratory, United States Department of Agriculture, Washington, D.C.