Pollinator Management Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

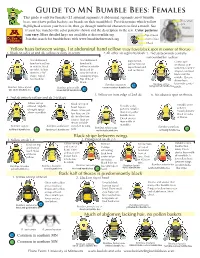

Guide to MN Bumble Bees: Females

Guide to MN Bumble Bees: Females This guide is only for females (12 antennal segments, 6 abdominal segments, most bumble Three small bees, most have pollen baskets, no beards on their mandibles). First determine which yellow eyes highlighted section your bee is in, then go through numbered characters to find a match. See if your bee matches the color patterns shown and the description in the text. Color patterns ® can vary. More detailed keys are available at discoverlife.org. Top of head Bee Front of face Squad Join the search for bumble bees with www.bumbleebeewatch.org Cheek Yellow hairs between wings, 1st abdominal band yellow (may have black spot in center of thorax) 1. Black on sides of 2nd ab, yellow or rusty in center 2.All other ab segments black 3. 2nd ab brownish centrally surrounded by yellow 2nd abdominal 2nd abdominal Light lemon Center spot band with yellow band with yellow hairs on on thorax with in middle, black yellow in middle top of head and sometimes faint V on sides. Yellow bordered by and on thorax. shaped extension often in a “W” rusty brown in a back from the shape. Top of swooping shape. middle. Queens head yellow. Top of head do not have black. Bombus impatiens Bombus affinis brownish central rusty patched bumble bee Bombus bimaculatus Bombus griseocollis common eastern bumble bee C patch. two-spotted bumble bee C brown-belted bumble bee C 5. Yellow on front edge of 2nd ab 6. No obvious spot on thorax. 4. 2nd ab entirely yellow and ab 3-6 black Yellow on top Black on top of Variable color of head. -

CUTOVERS AS POTENTIAL SUITABLE BEE HABITATS By

CUTOVERS AS POTENTIAL SUITABLE BEE HABITATS by Jasmine R. Pinksen A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science, Honours Environmental Science, Grenfell Campus Memorial University of Newfoundland April 2017 Corner Brook Newfoundland 2 Grenfell Campus Environmental Science Unit The undersigned certify that they have read, and recommend to the Environmental Science Unit (School of Science and the Environment) for acceptance, a thesis entitled “Cutovers as Potential Suitable Bee Habitats” submitted by Jasmine R. Pinksen in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science, Honours. _____________________________ Dr. Julie Sircom (thesis supervisor) _____________________________ Dr. Erin Fraser _____________________________ Dr. Joe Bowden April ____, 2017 3 Acknowledgements Thank you to the valuable research team members who helped with data collection for this project, Geena Arul Jothi, Megan Trotman, Tiffany Fillier, Erika Young, Nicole Walsh, and Abira Mumtaz. Thank you to Barry Elkins with Corner Brook Pulp and Paper Ltd. for financial support in 2015, maps of the logging areas around Corner Brook, NL, and his recommendations on site selection. Special thank you to my supervisor Dr. Julie Sircom, Dr. Erin Fraser and Dr. Joe Bowden for their feedback and support. 4 Abstract Bees are of great importance for pollinating agricultural crops and wild plant communities. Direct human activities such as urbanization, pesticide use, pollution, and introduction of species and pathogens as well as climate change are resulting in habitat loss and fragmentation for bees, causing declines in bee populations worldwide. Lack of suitable habitat is considered to be one of the main factors contributing to these declines. -

The Conservation Management and Ecology of Northeastern North

THE CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT AND ECOLOGY OF NORTHEASTERN NORTH AMERICAN BUMBLE BEES AMANDA LICZNER A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN BIOLOGY YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO September 2020 © Amanda Liczner, 2020 ii Abstract Bumble bees (Bombus spp.; Apidae) are among the pollinators most in decline globally with a main cause being habitat loss. Habitat requirements for bumble bees are poorly understood presenting a research gap. The purpose of my dissertation is to characterize the habitat of bumble bees at different spatial scales using: a systematic literature review of bumble bee nesting and overwintering habitat globally (Chapter 1); surveys of local and landcover variables for two at-risk bumble bee species (Bombus terricola, and B. pensylvanicus) in southern Ontario (Chapter 2); identification of conservation priority areas for bumble bee species in Canada (Chapter 3); and an analysis of the methodology for locating bumble bee nests using detection dogs (Chapter 4). The main findings were current literature on bumble bee nesting and overwintering habitat is limited and biased towards the United Kingdom and agricultural habitats (Ch.1). Bumble bees overwinter underground, often on shaded banks or near trees. Nests were mostly underground and found in many landscapes (Ch.1). B. terricola and B. pensylvanicus have distinct habitat characteristics (Ch.2). Landscape predictors explained more variation in the species data than local or floral resources (Ch.2). Among local variables, floral resources were consistently important throughout the season (Ch.2). Most bumble bee conservation priority areas are in western Canada, southern Ontario, southern Quebec and across the Maritimes and are most often located within woody savannas (Ch.3). -

Bumble Bees of CT-Females

Guide to CT Bumble Bees: Females This guide is only for females (12 antennal segments, 6 abdominal segments, most bumble bees, most have pollen baskets, no beards on their mandibles). First determine which yellow Three small eyes highlighted section your bee is in, then go through numbered characters to find a match. See if your bee matches the color patterns shown and the description in the text. Color patterns can vary. More detailed keys are available at discoverlife.org. Top of head Join the search for bumble bees with www.bumbleebeewatch.org Front of face Cheek Yellow hairs between wings, 1st abdominal band yellow (may have black spot in center of thorax) 1. Black on sides of 2nd ab, yellow or rusty in center 2.All other ab segments black 3. 2nd ab brownish centrally surrounded by yellow 2nd abdominal 2nd abdominal Light lemon Center spot band with yellow band with yellow hairs on on thorax with in middle, black yellow in middle top of head and sometimes faint V on sides. Yellow bordered by and on thorax. shaped extension often in a “W” rusty brown in a back from the shape. Top of swooping shape. middle. Queens head yellow. Top of head do not have black. Bombus impatiens Bombus affinis brownish central rusty patched bumble bee Bombus bimaculatus Bombus griseocollis common eastern bumble bee patch. two-spotted bumble bee brown-belted bumble bee 4. 2nd ab entirely yellow and ab 3-6 black 5. No obvious spot on thorax. Yellow on top Black on top of Variable color of head. -

Global Trends in Bumble Bee Health

EN65CH11_Cameron ARjats.cls December 18, 2019 20:52 Annual Review of Entomology Global Trends in Bumble Bee Health Sydney A. Cameron1,∗ and Ben M. Sadd2 1Department of Entomology, University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois 61801, USA; email: [email protected] 2School of Biological Sciences, Illinois State University, Normal, Illinois 61790, USA; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2020. 65:209–32 Keywords First published as a Review in Advance on Bombus, pollinator, status, decline, conservation, neonicotinoids, pathogens October 14, 2019 The Annual Review of Entomology is online at Abstract ento.annualreviews.org Bumble bees (Bombus) are unusually important pollinators, with approx- https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-011118- imately 260 wild species native to all biogeographic regions except sub- 111847 Saharan Africa, Australia, and New Zealand. As they are vitally important in Copyright © 2020 by Annual Reviews. natural ecosystems and to agricultural food production globally, the increase Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2020.65:209-232. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org All rights reserved in reports of declining distribution and abundance over the past decade ∗ Corresponding author has led to an explosion of interest in bumble bee population decline. We Access provided by University of Illinois - Urbana Champaign on 02/11/20. For personal use only. summarize data on the threat status of wild bumble bee species across bio- geographic regions, underscoring regions lacking assessment data. Focusing on data-rich studies, we also synthesize recent research on potential causes of population declines. There is evidence that habitat loss, changing climate, pathogen transmission, invasion of nonnative species, and pesticides, oper- ating individually and in combination, negatively impact bumble bee health, and that effects may depend on species and locality. -

Bumble Bees in Montana

Bumble Bees in Montana by Amelia C. Dolan, Middle School Specialist at Athlos Academies, Boise, ID and former MSU Graduate Student; Casey M. Delphia, Research Scientist, Departments of Ecology and LRES; and Lauren M. Kerzicnik, Insect Diagnostician and Assistant IPM Specialist Bumble bees are important native pollinators in wildlands and agricultural systems. Creating habitat to support bumble bees in yards and gardens can MontGuide be easy and is a great way to get involved in native bee conservation. MT201611AG New 7/16 BUMBLE BEES ARE IMPORTANT NATIVE Bumble bees are one group of bees that are able to pollinators in wildlands and agricultural systems. They “buzz pollinate,” which is important for certain types are easily recognized by their large size and colorful, hairy of plants such as blueberries and tomatoes. Within bodies. Queens are active in the spring and workers can the flowers of these types of plants, pollen is held in be seen throughout the summer into early fall. Creating small tube-like anthers (i.e. poricidal anthers), and is habitat to support bumble bees in yards and gardens can not released unless the anthers are vibrated. Bumble be easy and is a great way to get involved in native bee bees buzz pollinate by landing on the flower, grabbing conservation. the anthers with their jaws (i.e. mandibles), and then Bumble bees are in the family Apidae (includes honey quickly vibrating their flight muscles. The vibration bees, bumble bees, carpenter bees, cuckoo bees, sunflower effect is similar to an electric toothbrush and the pollen bees, and digger bees) and the is released. -

The Conservation Status of Bumble Bees of Canada, the USA, and Mexico

The Conservation Status of Bumble Bees of Canada, the USA, and Mexico Scott Hoffman Black, Rich Hatfield, Sarina Jepsen, Sheila Colla and Rémy Vandame Photo: Clay Bolt Importance of Bumble Bees There are 57 bumble bee species in Canada, US and Mexico. Hunt’s bumble bee; Bombus huntii , Photo: Clay Bolt Importance of Bumble Bees Important pollinator of many crops. Bombus sandersoni , Sanderson’s bumble bee Photo: Clay Bolt Importance of Bumble Bees Keystone pollinator in ecosystems. Yelllowheaded bumble bee, Bombus flavifrons Photo: Clay Bolt Bumble Bee Extinction Risk Assessment Network of 75+ bumble bee experts & specialists worldwide Goal: global bumble bee extinction risk assessment using consistent criteria Bumble Bee Extinction Risk Assessment IUCN Red List Criteria for Evaluating Extinction Risk • Used a database of 250,000+ specimen records (created from multiple data providers and compiled by Leif Richardson for Bumble Bees of North America) • Evaluate changes between recent (2002-2012) and historic (pre-2002): • Range (Extent of Occurrence) • Relative abundance • Persistence (50 km x 50 km grid cell occupancy) Sources: Hatfield et al. 2015 Bumble Bee Extinction Risk Assessment IUCN Red List Criteria for Evaluating Extinction Risk • Analyses informed application of Red List Categories; BBSG members provided review • This method was then adapted applied to South American and Mesoamerican bumble bees. Sources: Hatfield et al. 2015 Bumble Bee Extinction Risk Assessment Trilateral Region 6 4 5 28% of bumble bees Critically Endangered in Canada, the Endangered United States, and 7 Vulnerable Mexico are in an IUCN Threatened Near Threatened Category Least Concern 3 Data Deficient 32 Sources: Hatfield et al. -

An Abstract of the Thesis Of

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Sarah A. Maxfield-Taylor for the degree of Master of Science in Entomology presented on March 26, 2014. Title: Natural Enemies of Native Bumble Bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) in Western Oregon Abstract approved: _____________________________________________ Sujaya U. Rao Bumble bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) are important native pollinators in wild and agricultural systems, and are one of the few groups of native bees commercially bred for use in the pollination of a range of crops. In recent years, declines in bumble bees have been reported globally. One factor implicated in these declines, believed to affect bumble bee colonies in the wild and during rearing, is natural enemies. A diversity of fungi, protozoa, nematodes, and parasitoids has been reported to affect bumble bees, to varying extents, in different parts of the world. In contrast to reports of decline elsewhere, bumble bees have been thriving in Oregon on the West Coast of the U.S.A.. In particular, the agriculturally rich Willamette Valley in the western part of the state appears to be fostering several species. Little is known, however, about the natural enemies of bumble bees in this region. The objectives of this thesis were to: (1) identify pathogens and parasites in (a) bumble bees from the wild, and (b) bumble bees reared in captivity and (2) examine the effects of disease on bee hosts. Bumble bee queens and workers were collected from diverse locations in the Willamette Valley, in spring and summer. Bombus mixtus, Bombus nevadensis, and Bombus vosnesenskii collected from the wild were dissected and examined for pathogens and parasites, and these organisms were identified using morphological and molecular characteristics. -

Bumble Bee Surveys in the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area of Oregon and Washington

Bumble Bee Surveys in the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area of Oregon and Washington Final report from the Xerces Society to the U.S. Forest Service and Interagency Special Status/Sensitive Species Program (ISSSSP) Agreement L13AC00102, Modification 5 Bombus vosnesenskii on Balsamorhiza sagittata. Photo by Rich Hatfield, the Xerces Society. By Rich Hatfield, Sarina Jepsen, and Scott Black, the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation September 2017 1 Table of Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Methods ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 Site Selection ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Site Descriptions (west to east) ................................................................................................................ 7 T14ES27 (USFS) ..................................................................................................................................... 7 Cape Horn (USFS) ................................................................................................................................. -

Assessing Bumble Bee Diversity, Distribution, and Status for the Michigan Wildlife Action Plan

Assessing Bumble Bee Diversity, Distribution, and Status for the Michigan Wildlife Action Plan Prepared By: Logan M. Rowe, David L. Cuthrell, and Helen D. Enander Michigan Natural Features Inventory Michigan State University Extension P.O. Box 13036 Lansing, MI 48901 Prepared For: Michigan Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Division 12/17/2019 MNFI Report No. 2019-33 Suggested Citation: Rowe, L. M., D. L. Cuthrell., H. D. Enander. 2019. Assessing Bumble Bee Diversity, Distribution, and Status for the Michigan Wildlife Action Plan. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report Number 2019- 33, Lansing, USA. Copyright 2019 Michigan State University Board of Trustees. MSU Extension programs and materials are open to all without regard to race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, marital status or family status. Cover: Bombus terricola taken by D. L. Cuthrell Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................................................ iii Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Methods ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 Museum Searches .................................................................................................................................... -

1 Checklist of the Bumble Bees of British Columbia Rob Cannings

Checklist of the Bumble Bees of British Columbia Rob Cannings, Royal BC Museum (revised July 2011). Family Apidae: Subfamily Apinae: Tribe Bombini, Genus Bombus Bumble bees are large or medium sized bees conspicuously marked with yellow and black hairs, sometimes with additional red or white hairs. Most of the species collect pollen but those in the subgenus Psithyrus live as social parasites in the nests of other Bombus species. The genus is distributed in North and South America, in Eurasia and from the Philippines to western Indonesia. Some species have been introduced to other places, such as New Zealand and Australia. The following list of 32 known British Columbia species is assembled from various publications and museum collections. The list will probably be changed as more specimens are examined and should be considered preliminary. The taxonomy used is that of Natural History Museum (London) (Williams 2008), a fine, up-to-date systematic summary of the bumblebees of the world, although I have maintained B. occidentalis separate from B. terricola. Psithyrus has long been considered a genus separate from Bombus but most authorities now place it as a subgenus in Bombus; the four species in BC are listed separately for convenience. Except for Psithyrus, none of the subgenera often used in Bombus classification are included in this list. A few synonyms are listed (indents) to indicate the fate of some familiar names, especially those noted in Buckell (1951), Milliron (1973a, b) and Hurd (1979). Bombus impatiens Cresson, a common species from eastern North America, as of 2011 is an established alien species in the Lower Mainland. -

Invertebrates

State Wildlife Action Plan Update Appendix A-5 Species of Greatest Conservation Need Fact Sheets INVERTEBRATES Conservation Status and Concern Biology and Life History Distribution and Abundance Habitat Needs Stressors Conservation Actions Needed Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife 2015 Appendix A-5 SGCN Invertebrates – Fact Sheets Table of Contents What is Included in Appendix A-5 1 MILLIPEDE 2 LESCHI’S MILLIPEDE (Leschius mcallisteri)........................................................................................................... 2 MAYFLIES 4 MAYFLIES (Ephemeroptera) ................................................................................................................................ 4 [unnamed] (Cinygmula gartrelli) .................................................................................................................... 4 [unnamed] (Paraleptophlebia falcula) ............................................................................................................ 4 [unnamed] (Paraleptophlebia jenseni) ............................................................................................................ 4 [unnamed] (Siphlonurus autumnalis) .............................................................................................................. 4 [unnamed] (Cinygmula gartrelli) .................................................................................................................... 4 [unnamed] (Paraleptophlebia falcula) ...........................................................................................................