Copyrighted Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The People of Leonardo's Basement

The people of 26. Ant, or Anthony Davis 58. Fred Rogers Leonardo’s Basement 27. Slug, or Sean Daley 59. Steve Jevning The people - in popular culture, 28. Tony Sanneh 60. Tracy Nielsen business, politics, engineering, art, and technology - chosen for the 29. Lin-Manuel Miranda 61. Albert Einstein album cover redux have provided 30. Joan (of Art) Mondale 62. Maria Montessori inspiration to Leonardo’s Basement for 20 years. Many have a connection 31. Herbert Sellner 63. Nikola Tesla to Minnesota! 32. H.G. Wells 64. Leonardo da Vinci 1. Richard Dean Anderson, or 33. Rose Totino 65. Neal deGrasse Tyson MacGyver 34. Heidemarie Stefanyshyn- 66. John Dewey 2. Kofi Annan Piper 67. Frances McDormand or 3. Dave Arneson 35. Louie Anderson Marge Gunderson 4. Earl Bakken 36. Jeannette Piccard 68. Rocket girl 5. Ann Bancroft 37. Barry Kudrowitz 69. Ada Lovelace 6. Clyde Bellecourt 38. Jane Russell 70. Mary Tyler Moore or Mary Richards 7. Leeann Chin 39. Winona Ryder 71. Newton’s Apple 8. Judy Garland 40. June Marlowe 72. Wendell Anderson 9. Terry Lewis 41. Gordon Parks 73. Ralph Samuelson 10. Jimmy Jam 42. August Wilson 74. Jessica Lange 11. Kate DiCamillo 43. Rebecca Schatz 75. Trojan Horse 12. Dessa, or Margret Wander 44. Fred Rose 76. TARDIS 13. Walter Deubner 45. Cheryl Moeller 77. Cardboard castle 14. Reyn Guyer 46. Paul Bunyan 78. Millennium Falcon 15. Bob Dylan (Another Side of) 47. Mona Lisa 79. Chicken 16. Louise Erdich 48. Rocket J. "Rocky" Squirrel 80. Drum head, inspired by 17. Peter Docter 49. Bullwinkle J. -

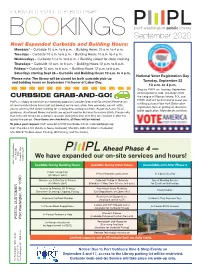

BOOKINGS September 2020 New! Expanded Curbside and Building Hours: Mondays* – Curbside 10 A.M

YOUR MONTHLY GUIDE TO PORT’S LIBRARY BOOKINGS September 2020 New! Expanded Curbside and Building Hours: Mondays* – Curbside 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • Building Hours 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Tuesdays – Curbside 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • Building Hours 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Wednesdays – Curbside 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • Building closed for deep cleaning. Thursdays – Curbside 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • Building Hours 12 p.m. to 6 p.m. Fridays – Curbside 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • Building Hours 12 p.m. to 6 p.m. Saturdays starting Sept 26 – Curbside and Building Hours 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. National Voter Registration Day *Please note: The library will be closed for both curbside pick-up and building hours on September 7 in honor of Labor Day. Tuesday, September 22 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Stop by PWPL on Tuesday, September 22 to register to vote. Volunteers from CURBSIDE GRAB-AND-GO! the League of Woman Voters, FOL and PWPL staff will be on hand to assist you PWPL is happy to continue our extremely popular Curbside Grab-and-Go service! Reserve any in filling out your New York State voter of your favorite library items (not just books!) online and, when they are ready, we will notify registration form or getting an absentee you to come by the library building for a contactless pickup out front. As per ALA and OCLC ballot application. More details to follow. guidance, all returned library materials are quarantined for 96 hours to ensure safety. -

Leituras Freudianas E Lacanianas Do Espaço Simbólico Hitchcock's Films O

Universidade de Aveiro Departamento de Línguas e Culturas Ano 2017 Mark William Poole Os Filmes de Hitchcock no Sofá: Leituras Freudianas e Lacanianas do Espaço Simbólico Hitchcock’s Films on the Couch: Freudian and Lacanian Readings of Symbolic Space Universidade de Aveiro Departamento de Línguas e Culturas Ano 2017 Mark William Poole Os Filmes de Hitchcock no Sofá: Leituras Freudianas e Lacanianas do Espaço Simbólico Hitchcock’s Films on the Couch: Freudian and Lacanian Readings of Symbolic Space Tese apresentada à Universidade de Aveiro para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Doutor em Estudos Culturais, realizada sob a orientação científica do Doutor Anthony David Barker, Professor Associado do Departamento de Línguas e Culturas da Universidade de Aveiro o júri Doutor Carlos Manuel da Rocha Borges de Azevedo, Professor Catedrático, Faculdade de Letras, Universidade do Porto. Doutor Mário Carlos Fernandes Avelar, Professor Catedrático, Universidade Aberta, Lisboa. Doutor Anthony David Barker, Professor Associado, Universidade de Aveiro (orientador). Doutor Kenneth David Callahan, Professor Associado, Universidade de Aveiro. Doutor Nelson Troca Zagalo, Professor Auxiliar, Universidade do Minho. presidente Doutor Nuno Miguel Gonçalves Borges de Carvalho, Reitor da Universidade de Aveiro. agradecimentos Primarily, I would like to thank Isabel Pereira, without whose generosity this entire process would not have been possible. She believes in supporting all types of education and I cannot express my gratitude enough. I express equal gratitude to Marta Correia, who has been the Alma Reville of this thesis. She has had the patience to listen to my ideas and offer her invaluable insights, while proofreading and criticising the chapters as this thesis evolved. -

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

"Sounds Like a Spy Story": the Espionage Thrillers of Alfred

University of Mary Washington Eagle Scholar Student Research Submissions 4-29-2016 "Sounds Like a Spy Story": The Espionage Thrillers of Alfred Hitchcock in Twentieth-Century English and American Society, from The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) to Topaz (1969) Kimberly M. Humphries Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Humphries, Kimberly M., ""Sounds Like a Spy Story": The Espionage Thrillers of Alfred Hitchcock in Twentieth-Century English and American Society, from The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) to Topaz (1969)" (2016). Student Research Submissions. 47. https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research/47 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by Eagle Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research Submissions by an authorized administrator of Eagle Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "SOUNDS LIKE A SPY STORY": THE ESPIONAGE THRILLERS OF ALFRED HITCHCOCK IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY ENGLISH AND AMERICAN SOCIETY, FROM THE MAN WHO KNEW TOO MUCH (1934) TO TOPAZ (1969) An honors paper submitted to the Department of History and American Studies of the University of Mary Washington in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Departmental Honors Kimberly M Humphries April 2016 By signing your name below, you affirm that this work is the complete and final version of your paper submitted in partial fulfillment of a degree from the University of Mary Washington. You affirm the University of Mary Washington honor pledge: "I hereby declare upon my word of honor that I have neither given nor received unauthorized help on this work." Kimberly M. -

The Media World: a New Collaboration Was Born

The Media World: A New Collaboration Was Born MeCCSA and AMPE Joint Annual Conference. 5- 7 January 2005, University of Lincoln A report by Serena Formica, University of Nottingham, UK There was much anticipation and expectation leading up to the 2005 MeCCSA conference at the University of Lincoln. This was due to the event being the first joint MeCCSA (Media, Communications and Cultural Studies Association) and AMPE (Association of Media Practice Educators) conference. The purpose of this union was to highlight the common features of both organisations, such as interest in media, Cultural Studies, pedagogy -- all of them reflected in the numerous panels throughout the three-day meeting. Plenary sessions interspersed the many panels, the first of which was presented by Ursula Maier-Rabler (Director of the Centre for Advanced Studies and Research in Information and Communication Technologies and Society, University of Salzburg), who presented a paper entitled "Why do ICTs Matter? The Cultural-Social Milieu as Invisible Underpinning of New Information and Communication Technologies". Dr. Maier-Rabler highlighted the increasing importance of ICTs, considered as a Digital Network, characterised by its universality and non-linearity of contents. As Paul Virilio pointed out, ICTs are permeated by a constant acceleration, which emphasises its element of 'unfinishedness'. The cultural milieu surrounding ICTs was presented as divided into four major social-geographical areas: Social- conservative, Social-democratic, Protestant-liberal and Liberal-conservative. Maier-Rabler observed that the former belong to a collective form of State, whereas the latter belong to a form that is more individualistic. Furthermore, Dr. Maier-Rabler analysed ICTs' perspectives in terms of communication and infrastructure -- media (defined by a shift from programmes to services, media systems to infrastructure and recipient to users) and network (at a technical and social level). -

Hitchcock's Appetites

McKittrick, Casey. "Epilogue." Hitchcock’s Appetites: The corpulent plots of desire and dread. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 159–163. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 28 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501311642.0011>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 28 September 2021, 08:18 UTC. Copyright © Casey McKittrick 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. Epilogue itchcock and his works continue to experience life among generation Y Hand beyond, though it is admittedly disconcerting to walk into an undergraduate lecture hall and see few, if any, lights go on at the mention of his name. Disconcerting as it may be, all ill feelings are forgotten when I watch an auditorium of eighteen- to twenty-one-year-olds transported by the emotions, the humor, and the compulsions of his cinema. But certainly the college classroom is not the only guardian of Hitchcock ’ s fl ame. His fi lms still play at retrospectives, in fi lm festivals, in the rising number of fi lm studies classes in high schools, on Turner Classic Movies, and other networks devoted to the “ oldies. ” The wonderful Bates Motel has emerged as a TV serial prequel to Psycho , illustrating the formative years of Norman Bates; it will see a second season in the coming months. Alfred Hitchcock Presents and The Alfred Hitchcock Hour are still in strong syndication. Both his fi lms and television shows do very well in collections and singly on Amazon and other e-commerce sites. -

Music, Memory and Repression in Hitchcock's Vertigo (1958)

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 22 | 2021 Unheard Possibilities: Reappraising Classical Film Music Scoring and Analysis Music, Memory and Repression in Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) Christophe Gelly Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/36484 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.36484 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Christophe Gelly, “Music, Memory and Repression in Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958)”, Miranda [Online], 22 | 2021, Online since 02 March 2021, connection on 26 April 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ miranda/36484 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.36484 This text was automatically generated on 26 April 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Music, Memory and Repression in Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) 1 Music, Memory and Repression in Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) Christophe Gelly Introduction 1 Alfred Hitchcock somehow retained a connection with the aesthetics of the silent film era in which he made his debut throughout his career, which can account for his reluctance to include dialogues when their content can be conveyed visually.1 His reluctance never concerned music, however, since music was performed during the screening of silent films generally, though an experimental drive in the director’s perspective on that subject can be observed through the fact for instance that The Birds (1963) dispenses -

Hitchcock's Appetites

McKittrick, Casey. "The pleasures and pangs of Hitchcockian consumption." Hitchcock’s Appetites: The corpulent plots of desire and dread. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 65–99. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 28 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501311642.0007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 28 September 2021, 16:41 UTC. Copyright © Casey McKittrick 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 3 The pleasures and pangs of Hitchcockian consumption People say, “ Why don ’ t you make more costume pictures? ” Nobody in a costume picture ever goes to the toilet. That means, it ’ s not possible to get any detail into it. People say, “ Why don ’ t you make a western? ” My answer is, I don ’ t know how much a loaf of bread costs in a western. I ’ ve never seen anybody buy chaps or being measured or buying a 10 gallon hat. This is sometimes where the drama comes from for me. 1 y 1942, Hitchcock had acquired his legendary moniker the “ Master of BSuspense. ” The nickname proved more accurate and durable than the title David O. Selznick had tried to confer on him— “ the Master of Melodrama ” — a year earlier, after Rebecca ’ s release. In a fi fty-four-feature career, he deviated only occasionally from his tried and true suspense fi lm, with the exceptions of his early British assignments, the horror fi lms Psycho and The Birds , the splendid, darkly comic The Trouble with Harry , and the romantic comedy Mr. -

Innovators: Filmmakers

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES INNOVATORS: FILMMAKERS David W. Galenson Working Paper 15930 http://www.nber.org/papers/w15930 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 April 2010 The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2010 by David W. Galenson. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Innovators: Filmmakers David W. Galenson NBER Working Paper No. 15930 April 2010 JEL No. Z11 ABSTRACT John Ford and Alfred Hitchcock were experimental filmmakers: both believed images were more important to movies than words, and considered movies a form of entertainment. Their styles developed gradually over long careers, and both made the films that are generally considered their greatest during their late 50s and 60s. In contrast, Orson Welles and Jean-Luc Godard were conceptual filmmakers: both believed words were more important to their films than images, and both wanted to use film to educate their audiences. Their greatest innovations came in their first films, as Welles made the revolutionary Citizen Kane when he was 26, and Godard made the equally revolutionary Breathless when he was 30. Film thus provides yet another example of an art in which the most important practitioners have had radically different goals and methods, and have followed sharply contrasting life cycles of creativity. -

European Journal of American Studies, 5-4 | 2010 “Don’T Be Frightened Dear … This Is Hollywood”: British Filmmakers in Early A

European journal of American studies 5-4 | 2010 Special Issue: Film “Don’t Be Frightened Dear … This Is Hollywood”: British Filmmakers in Early American Cinema Ian Scott Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/8751 DOI: 10.4000/ejas.8751 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference Ian Scott, ““Don’t Be Frightened Dear … This Is Hollywood”: British Filmmakers in Early American Cinema”, European journal of American studies [Online], 5-4 | 2010, document 5, Online since 15 November 2010, connection on 08 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ejas/8751 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ejas.8751 This text was automatically generated on 8 July 2021. Creative Commons License “Don’t Be Frightened Dear … This Is Hollywood”: British Filmmakers in Early A... 1 “Don’t Be Frightened Dear … This Is Hollywood”: British Filmmakers in Early American Cinema Ian Scott 1 “Don't be frightened, dear – this – this – is Hollywood.” 2 Noël Coward recited these words of encouragement told to him by the actress Laura Hope-Crews on a Christmas visit to Hollywood in 1929. In typically acerbic fashion, he retrospectively judged his experiences in Los Angeles to be “unreal and inconclusive, almost as though they hadn't happened at all.” Coward described his festive jaunt through Hollywood’s social merry-go-round as like careering “through the side-shows of some gigantic pleasure park at breakneck speed” accompanied by “blue-ridged cardboard mountains, painted skies [and] elaborate grottoes peopled with several familiar figures.”1 3 Coward’s first visit persuaded him that California was not the place to settle and he for one only ever made fleeting visits to the movie colony, but the description he offered, and the delicious dismissal of Hollywood’s “fabricated” community, became common currency if one examines other British accounts of life on the west coast at this time. -

![1940-08-29, [P ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5100/1940-08-29-p-805100.webp)

1940-08-29, [P ]

SPECIAL LABOR EDITION THE NEWARK LEADER, THURSDAY, AUGUST 29, 1940 SPECIAL LABOR EDITION family visited Mr. and Mrs. Cary Newark Men Will McKinney Sunday. MIDLAND - AUDITORIUM SHOWS Miss Mary Klingenberg of Unemployment Bureau of Athens visited Mr. and Mrs. Enjoy Sailing Cary McKinney on Sunday after “SOUTH OF PAGO PAGO” noon. Now playing, Thursday to Mrs. Blanche Evans, son Rus Saturday, August 29-31, at the Schooner Trip sell, her daughter Mrs. Violet Great Importance to Workers Midland theatre — a thrilling Brunner, her grandson Llewellyn tropic love drama of the south Jerome Norpell, Wm. M. Ser Courson and Mrs. Nan Minego Of great importance to the days or more. Members of the seas with a stellar cast of play geant, George Pfeffer, John went on a picnic to Baughman’s Welfare of Licking county’s staff also made 1950 calls on ers, enacting a story of thrilling Spencer and Dr. Paul McClure, park Sunday. workers is District Office No. 38, prospective employers, explain adventure. “South of Pago will leave this Friday for Maine, Mrs. Blanche Evans visited Bureau of Unemployment Com ing the service and soliciting op Pago” starring Jon Hall, Fran on a short vacation trip. It is friends in Delaware and Marion pensation, located at 28-30 North enings. ces Farmer, Victor McLagen and their plan to sail on a Small last week. Fourth street. The nine mem One of the most successful em others concerns the strange ad schooner off the coast of Maine, Mr. and Mrs. Earl Gleckler bers of the staff consist of John ployment campaigns conducted ventures of Bucko Larson and and enjoy the fabulous fishing and daughter and Leroy Rowe of Gilbert, manager, and two sen in Newark during the period Ruby Taylor, who undertake an grounds and beautiful scenery Martinsburg road were Sunday ior and two junior interviewers; was the “Clean Up—Give a Job” adventure to the famous pearl along the coast.