Supporting Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Old Data and Friends Improve with Age: Advancements with the Updated Tools of Genenetwork

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.24.445383; this version posted May 25, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Old data and friends improve with age: Advancements with the updated tools of GeneNetwork Alisha Chunduri1, David G. Ashbrook2 1Department of Biotechnology, Chaitanya Bharathi Institute of Technology, Hyderabad 500075, India 2Department of Genetics, Genomics and Informatics, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, TN 38163, USA Abstract Understanding gene-by-environment interactions is important across biology, particularly behaviour. Families of isogenic strains are excellently placed, as the same genome can be tested in multiple environments. The BXD’s recent expansion to 140 strains makes them the largest family of murine isogenic genomes, and therefore give great power to detect QTL. Indefinite reproducible genometypes can be leveraged; old data can be reanalysed with emerging tools to produce novel biological insights. To highlight the importance of reanalyses, we obtained drug- and behavioural-phenotypes from Philip et al. 2010, and reanalysed their data with new genotypes from sequencing, and new models (GEMMA and R/qtl2). We discover QTL on chromosomes 3, 5, 9, 11, and 14, not found in the original study. We narrowed down the candidate genes based on their ability to alter gene expression and/or protein function, using cis-eQTL analysis, and variants predicted to be deleterious. Co-expression analysis (‘gene friends’) and human PheWAS were used to further narrow candidates. -

The Basal Bodies of Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii Susan K

Dutcher and O’Toole Cilia (2016) 5:18 DOI 10.1186/s13630-016-0039-z Cilia REVIEW Open Access The basal bodies of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii Susan K. Dutcher1* and Eileen T. O’Toole2 Abstract The unicellular green alga, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, is a biflagellated cell that can swim or glide. C. reinhardtii cells are amenable to genetic, biochemical, proteomic, and microscopic analysis of its basal bodies. The basal bodies contain triplet microtubules and a well-ordered transition zone. Both the mother and daughter basal bodies assemble flagella. Many of the proteins found in other basal body-containing organisms are present in the Chlamydomonas genome, and mutants in these genes affect the assembly of basal bodies. Electron microscopic analysis shows that basal body duplication is site-specific and this may be important for the proper duplication and spatial organization of these organelles. Chlamydomonas is an excellent model for the study of basal bodies as well as the transition zone. Keywords: Site-specific basal body duplication, Cartwheel, Transition zone, Centrin fibers Phylogeny and conservation of proteins Centrin, SPD2/CEP192, Asterless/CEP152; CEP70, The green lineage or Viridiplantae consists of the green delta-tubulin, and epsilon-tubulin. Chlamydomonas has algae, which include Chlamydomonas, the angiosperms homologs of all of these based on sequence conservation (the land plants), and the gymnosperms (conifers, cycads, except PLK4, CEP152, and CEP192. Several lines of evi- ginkgos). They are grouped together because they have dence suggests that CEP152, CEP192, and PLK4 interact chlorophyll a and b and lack phycobiliproteins. The green [20, 52] and their concomitant absence in several organ- algae together with the cycads and ginkgos have basal isms suggests that other mechanisms exist that allow for bodies and cilia, while the angiosperms and conifers have control of duplication [4]. -

Par6c Is at the Mother Centriole and Controls Centrosomal Protein

860 Research Article Par6c is at the mother centriole and controls centrosomal protein composition through a Par6a-dependent pathway Vale´rian Dormoy, Kati Tormanen and Christine Su¨ tterlin* Department of Developmental and Cell Biology, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA 92697-2300, USA *Author for correspondence ([email protected]) Accepted 3 December 2012 Journal of Cell Science 126, 860–870 ß 2013. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd doi: 10.1242/jcs.121186 Summary The centrosome contains two centrioles that differ in age, protein composition and function. This non-membrane bound organelle is known to regulate microtubule organization in dividing cells and ciliogenesis in quiescent cells. These specific roles depend on protein appendages at the older, or mother, centriole. In this study, we identified the polarity protein partitioning defective 6 homolog gamma (Par6c) as a novel component of the mother centriole. This specific localization required the Par6c C-terminus, but was independent of intact microtubules, the dynein/dynactin complex and the components of the PAR polarity complex. Par6c depletion resulted in altered centrosomal protein composition, with the loss of a large number of proteins, including Par6a and p150Glued, from the centrosome. As a consequence, there were defects in ciliogenesis, microtubule organization and centrosome reorientation during migration. Par6c interacted with Par3 and aPKC, but these proteins were not required for the regulation of centrosomal protein composition. Par6c also associated with Par6a, which controls protein recruitment to the centrosome through p150Glued. Our study is the first to identify Par6c as a component of the mother centriole and to report a role of a mother centriole protein in the regulation of centrosomal protein composition. -

Supplemental Information Proximity Interactions Among Centrosome

Current Biology, Volume 24 Supplemental Information Proximity Interactions among Centrosome Components Identify Regulators of Centriole Duplication Elif Nur Firat-Karalar, Navin Rauniyar, John R. Yates III, and Tim Stearns Figure S1 A Myc Streptavidin -tubulin Merge Myc Streptavidin -tubulin Merge BirA*-PLK4 BirA*-CEP63 BirA*- CEP192 BirA*- CEP152 - BirA*-CCDC67 BirA* CEP152 CPAP BirA*- B C Streptavidin PCM1 Merge Myc-BirA* -CEP63 PCM1 -tubulin Merge BirA*- CEP63 DMSO - BirA* CEP63 nocodazole BirA*- CCDC67 Figure S2 A GFP – + – + GFP-CEP152 + – + – Myc-CDK5RAP2 + + + + (225 kDa) Myc-CDK5RAP2 (216 kDa) GFP-CEP152 (27 kDa) GFP Input (5%) IP: GFP B GFP-CEP152 truncation proteins Inputs (5%) IP: GFP kDa 1-7481-10441-1290218-1654749-16541045-16541-7481-10441-1290218-1654749-16541045-1654 250- Myc-CDK5RAP2 150- 150- 100- 75- GFP-CEP152 Figure S3 A B CEP63 – – + – – + GFP CCDC14 KIAA0753 Centrosome + – – + – – GFP-CCDC14 CEP152 binding binding binding targeting – + – – + – GFP-KIAA0753 GFP-KIAA0753 (140 kDa) 1-496 N M C 150- 100- GFP-CCDC14 (115 kDa) 1-424 N M – 136-496 M C – 50- CEP63 (63 kDa) 1-135 N – 37- GFP (27 kDa) 136-424 M – kDa 425-496 C – – Inputs (2%) IP: GFP C GFP-CEP63 truncation proteins D GFP-CEP63 truncation proteins Inputs (5%) IP: GFP Inputs (5%) IP: GFP kDa kDa 1-135136-424425-4961-424136-496FL Ctl 1-135136-424425-4961-424136-496FL Ctl 1-135136-424425-4961-424136-496FL Ctl 1-135136-424425-4961-424136-496FL Ctl Myc- 150- Myc- 100- CCDC14 KIAA0753 100- 100- 75- 75- GFP- GFP- 50- CEP63 50- CEP63 37- 37- Figure S4 A siCtl -

Centrin2 Regulates CP110 Removal in Primary Cilium Formation

Published March 9, 2015 JCB: Report Centrin2 regulates CP110 removal in primary cilium formation Suzanna L. Prosser and Ciaran G. Morrison Centre for Chromosome Biology, School of Natural Sciences, National University of Ireland, Galway, Galway, Ireland rimary cilia are antenna-like sensory microtubule ciliogenesis in chicken DT40 B lymphocytes required cen- structures that extend from basal bodies, plasma trin2. We disrupted CETN2 in human retinal pigmented P membrane–docked mother centrioles. Cellular qui- epithelial cells, and despite having intact centrioles, they escence potentiates ciliogenesis, but the regulation of basal were unable to make cilia upon serum starvation, show- body formation is not fully understood. We used reverse ing abnormal localization of distal appendage proteins genetics to test the role of the small calcium-binding pro- and failing to remove the ciliation inhibitor CP110. Knock- tein, centrin2, in ciliogenesis. Primary cilia arise in most down of CP110 rescued ciliation in CETN2-deficient cells. cell types but have not been described in lymphocytes. Thus, centrin2 regulates primary ciliogenesis through con- We show here that serum starvation of transformed, cul- trolling CP110 levels. Downloaded from tured B and T cells caused primary ciliogenesis. Efficient Introduction Primary cilia are crucial for several signal transduction path- the immune synapse, a membrane region at which cells of on April 19, 2017 ways (Goetz and Anderson, 2010). Their assembly is an or- the immune system contact their target cells, helps to estab- dered process that must be closely integrated with the cell cycle lish a specialized structure that has several similarities with cilia because of the dual roles of centrioles in ciliation and in mito- (Stinchcombe and Griffiths, 2014). -

The Transformation of the Centrosome Into the Basal Body: Similarities and Dissimilarities Between Somatic and Male Germ Cells and Their Relevance for Male Fertility

cells Review The Transformation of the Centrosome into the Basal Body: Similarities and Dissimilarities between Somatic and Male Germ Cells and Their Relevance for Male Fertility Constanza Tapia Contreras and Sigrid Hoyer-Fender * Göttingen Center of Molecular Biosciences, Johann-Friedrich-Blumenbach Institute for Zoology and Anthropology-Developmental Biology, Faculty of Biology and Psychology, Georg-August University of Göttingen, 37077 Göttingen, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The sperm flagellum is essential for the transport of the genetic material toward the oocyte and thus the transmission of the genetic information to the next generation. During the haploid phase of spermatogenesis, i.e., spermiogenesis, a morphological and molecular restructuring of the male germ cell, the round spermatid, takes place that includes the silencing and compaction of the nucleus, the formation of the acrosomal vesicle from the Golgi apparatus, the formation of the sperm tail, and, finally, the shedding of excessive cytoplasm. Sperm tail formation starts in the round spermatid stage when the pair of centrioles moves toward the posterior pole of the nucleus. The sperm tail, eventually, becomes located opposed to the acrosomal vesicle, which develops at the anterior pole of the nucleus. The centriole pair tightly attaches to the nucleus, forming a nuclear membrane indentation. An Citation: Tapia Contreras, C.; articular structure is formed around the centriole pair known as the connecting piece, situated in the Hoyer-Fender, S. The Transformation neck region and linking the sperm head to the tail, also named the head-to-tail coupling apparatus or, of the Centrosome into the Basal in short, HTCA. -

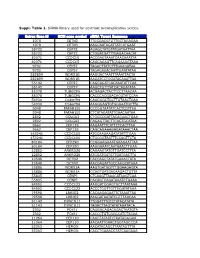

Suppl. Table 1

Suppl. Table 1. SiRNA library used for centriole overduplication screen. Entrez Gene Id NCBI gene symbol siRNA Target Sequence 1070 CETN3 TTGCGACGTGTTGCTAGAGAA 1070 CETN3 AAGCAATAGATTATCATGAAT 55722 CEP72 AGAGCTATGTATGATAATTAA 55722 CEP72 CTGGATGATTTGAGACAACAT 80071 CCDC15 ACCGAGTAAATCAACAAATTA 80071 CCDC15 CAGCAGAGTTCAGAAAGTAAA 9702 CEP57 TAGACTTATCTTTGAAGATAA 9702 CEP57 TAGAGAAACAATTGAATATAA 282809 WDR51B AAGGACTAATTTAAATTACTA 282809 WDR51B AAGATCCTGGATACAAATTAA 55142 CEP27 CAGCAGATCACAAATATTCAA 55142 CEP27 AAGCTGTTTATCACAGATATA 85378 TUBGCP6 ACGAGACTACTTCCTTAACAA 85378 TUBGCP6 CACCCACGGACACGTATCCAA 54930 C14orf94 CAGCGGCTGCTTGTAACTGAA 54930 C14orf94 AAGGGAGTGTGGAAATGCTTA 5048 PAFAH1B1 CCCGGTAATATCACTCGTTAA 5048 PAFAH1B1 CTCATAGATATTGAACAATAA 2802 GOLGA3 CTGGCCGATTACAGAACTGAA 2802 GOLGA3 CAGAGTTACTTCAGTGCATAA 9662 CEP135 AAGAATTTCATTCTCACTTAA 9662 CEP135 CAGCAGAAAGAGATAAACTAA 153241 CCDC100 ATGCAAGAAGATATATTTGAA 153241 CCDC100 CTGCGGTAATTTCCAGTTCTA 80184 CEP290 CCGGAAGAAATGAAGAATTAA 80184 CEP290 AAGGAAATCAATAAACTTGAA 22852 ANKRD26 CAGAAGTATGTTGATCCTTTA 22852 ANKRD26 ATGGATGATGTTGATGACTTA 10540 DCTN2 CACCAGCTATATGAAACTATA 10540 DCTN2 AACGAGATTGCCAAGCATAAA 25886 WDR51A AAGTGATGGTTTGGAAGAGTA 25886 WDR51A CCAGTGATGACAAGACTGTTA 55835 CENPJ CTCAAGTTAAACATAAGTCAA 55835 CENPJ CACAGTCAGATAAATCTGAAA 84902 CCDC123 AAGGATGGAGTGCTTAATAAA 84902 CCDC123 ACCCTGGTTGTTGGATATAAA 79598 LRRIQ2 CACAAGAGAATTCTAAATTAA 79598 LRRIQ2 AAGGATAATATCGTTTAACAA 51143 DYNC1LI1 TTGGATTTGTCTATACATATA 51143 DYNC1LI1 TAGACTTAGTATATAAATACA 2302 FOXJ1 CAGGACAGACAGACTAATGTA -

An Exome-Wide Sequencing Study of Lipid Response to High-Fat Meal and Fenofibrate in Caucasians from the GOLDN Cohort

Washington University School of Medicine Digital Commons@Becker Open Access Publications 2018 An exome-wide sequencing study of lipid response to high-fat meal and fenofibrate in Caucasians from the GOLDN cohort Xin Geng Ping An Mary F. Feitosa Michael A. Province et al. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs Supplemental Material can be found at: http://www.jlr.org/content/suppl/2018/02/20/jlr.P080333.DC1 .html patient-oriented and epidemiological research An exome-wide sequencing study of lipid response to high-fat meal and fenofibrate in Caucasians from the GOLDN cohort Xin Geng,* Marguerite R. Irvin,† Bertha Hidalgo,† Stella Aslibekyan,† Vinodh Srinivasasainagendra,§ Ping An,‡ Alexis C. Frazier-Wood,|| Hemant K. Tiwari,§ Tushar Dave,# Kathleen Ryan,# Jose M. Ordovas,$,**,†† Robert J. Straka,§§ Mary F. Feitosa,‡ Paul N. Hopkins,‡‡ Ingrid Borecki,|| || Michael A. Province,‡ Braxton D. Mitchell,# Donna K. Arnett,1,## and Degui Zhi1,*,$$ School of Biomedical Informatics* and School of Public Health,$$ The University of Texas Health Downloaded from Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX 77030; Departments of Epidemiology† and Biostatistics,§ University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL 35233; Division of Statistical Genomics, Department of Genetics,‡ Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO 63110; US Department of Agriculture/Agricultural Research Service Children’s Nutrition Research Center,|| Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX 77030; Department of Medicine, Division -

Whole Exome Sequencing Identifies Causative Mutations in the Majority of Consanguineous Or Familial Cases with Childhood-Onset I

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Kidney Manuscript Author Int. Author manuscript; Manuscript Author available in PMC 2016 August 01. Published in final edited form as: Kidney Int. 2016 February ; 89(2): 468–475. doi:10.1038/ki.2015.317. Whole exome sequencing identifies causative mutations in the majority of consanguineous or familial cases with childhood- onset increased renal echogenicity Daniela A. Braun#1, Markus Schueler#1, Jan Halbritter1, Heon Yung Gee1, Jonathan D. Porath1, Jennifer A. Lawson1, Rannar Airik1, Shirlee Shril1, Susan J. Allen2, Deborah Stein1, Adila Al Kindy3, Bodo B. Beck4, Nurcan Cengiz5, Khemchand N. Moorani6, Fatih Ozaltin7,8,9, Seema Hashmi10, John A. Sayer11, Detlef Bockenhauer12, Neveen A. Soliman13,14, Edgar A. Otto2, Richard P. Lifton15,16,17, and Friedhelm Hildebrandt1,17 1Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, Boston Children's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA 2Department of Pediatrics, University of Michigan, Michigan, USA 3Department of Genetics, Sultan Qaboos University Hospital, Sultanate of Oman 4Institute for Human Genetics, University of Cologne, Germany 5Baskent University, School of Medicine, Adana Medical Training and Research Center, Department of Pediatric Nephrology, Adana, Turkey 6Department of Pediatric Nephrology, National Institute of Child Health, Karachi 75510, Pakistan 7Faculty of Medicine, Department of Pediatric Nephrology, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey 8Nephrogenetics Laboratory, Faculty of Medicine, -

TALPID3 and ANKRD26 Selectively Orchestrate FBF1 Localization and Cilia Gating

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16042-w OPEN TALPID3 and ANKRD26 selectively orchestrate FBF1 localization and cilia gating Hao Yan 1,2,3,7, Chuan Chen4,7, Huicheng Chen1,2,3, Hui Hong 1, Yan Huang4,5, Kun Ling4,5, ✉ ✉ Jinghua Hu4,5,6 & Qing Wei 3 Transition fibers (TFs) regulate cilia gating and make the primary cilium a distinct functional entity. However, molecular insights into the biogenesis of a functional cilia gate remain 1234567890():,; elusive. In a forward genetic screen in Caenorhabditis elegans, we uncover that TALP-3, a homolog of the Joubert syndrome protein TALPID3, is a TF-associated component. Genetic analysis reveals that TALP-3 coordinates with ANKR-26, the homolog of ANKRD26, to orchestrate proper cilia gating. Mechanistically, TALP-3 and ANKR-26 form a complex with key gating component DYF-19, the homolog of FBF1. Co-depletion of TALP-3 and ANKR-26 specifically impairs the recruitment of DYF-19 to TFs. Interestingly, in mammalian cells, TALPID3 and ANKRD26 also play a conserved role in coordinating the recruitment of FBF1 to TFs. We thus report a conserved protein module that specifically regulates the functional component of the ciliary gate and suggest a correlation between defective gating and cilio- pathy pathogenesis. 1 CAS Key Laboratory of Insect Developmental and Evolutionary Biology, CAS Center for Excellence in Molecular Plant Sciences, Institute of Plant Physiology and Ecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai 200032, China. 2 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100039, China. 3 Center for Reproduction and Health Development, Institute of Biomedicine and Biotechnology, Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced Technology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), Shenzhen 518055, China. -

CEP164-Null Cells Generated by Genome Editing Show a Ciliation Defect with Intact DNA Repair Capacity Owen M

© 2016. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Cell Science (2016) 129, 1769-1774 doi:10.1242/jcs.186221 SHORT REPORT CEP164-null cells generated by genome editing show a ciliation defect with intact DNA repair capacity Owen M. Daly1, David Gaboriau1,*, Kadin Karakaya2, Sinéad King1, Tiago J. Dantas1,‡, Pierce Lalor3, Peter Dockery3, Alwin Krämer2 and Ciaran G. Morrison1,§ ABSTRACT induced by the removal of growth factors, facilitates ciliogenesis Primary cilia are microtubule structures that extend from the distal end (Kobayashi and Dynlacht, 2011). Current models associate primary of the mature, mother centriole. CEP164 is a component of the distal cilia with cell cycle exit and reduced proliferation, although the appendages carried by the mother centriole that is required for underlying mechanisms of such a link are not well defined (Goto primary cilium formation. Recent data have implicated CEP164 as a et al., 2013). CEP164 ciliopathy gene and suggest that CEP164 plays some roles in the encodes a centriolar appendage protein that is required DNA damage response (DDR). We used reverse genetics to test the for ciliogenesis (Graser et al., 2007; Schmidt et al., 2012). It has also role of CEP164 in the DDR. We found that conditional depletion of been implicated in modulating the DNA damage response (DDR), CEP164 in chicken DT40 cells using an auxin-inducible degron led to particularly CHK1 (Sivasubramaniam et al., 2008). CEP164 was no increase in sensitivity to DNA damage induced by ionising or initially identified in a proteomic analysis of the centrosome and, ultraviolet irradiation. Disruption of CEP164 in human retinal later, as a component of the distal appendages whose depletion by pigmented epithelial cells blocked primary cilium formation but did small interfering RNA (siRNA) treatment caused a marked not affect cellular proliferation or cellular responses to ionising or reduction in primary cilium formation (Andersen et al., 2003; ultraviolet irradiation. -

Anchoring the Pole Plasm

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS Anchoring the pole plasm A kinesin in ciliogenesis Ectopic expression of Kif24 specifically desta- bilizes centriolar, but not cytoplasmic, microtu- The pole plasm, a cytoplasmic region contain- bules. In vitro experiments confirm the ability of ing maternal mRNAs and proteins at the pos- Kif24 to bind and depolymerize microtubules. terior of Drosophila oocytes, is essential for Furthermore, Kif24 overexpression suppresses germline and abdominal development. Pole cilia formation in starved cells, but, surprisingly, plasm assembly is initiated by the microtubule- also suppresses centriole elongation induced by dependent transport of oskar (osk) mRNA to Cep97 depletion. In both cases the microtubule the posterior, where the Osk protein stimulates depolymerizing domain of Kif24 is required. endocytic and actin-remodelling events essen- Thus, the authors suggest that Kif24 sup- tial for germ plasm functionality. Nakamura and presses cilia assembly from the mother cen- colleagues (Development 138, 2523–2532; 2011) triole through two mechanisms: by stabilizing have found that Mon2, a protein associated with or recruiting CP110 and through microtubule Golgi and endosomes, acts downstream of Osk remodelling. CKR to remodel cortical actin and anchor the pole In serum-starved cells, the primary cilium plasm. mon2 was identified in a screen for genes is nucleated from the mother centriole. required for the localization of the pole plasm Both cilia formation and centriole elonga- component Vasa. The authors found that Osk- tion is restricted by the centrosomal protein miRNA control of glucose induced formation of actin protrusions was CP110. Brian Dynlacht and co-workers have metabolism perturbed in mon2 mutants, as seen previously now identified the kinesin Kif24 as a CP110- in endosomal GTPase rab5 mutants.