Building Societies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lender Panel List December 2019

Threemo - Available Lender Panels (16/12/2019) Accord (YBS) Amber Homeloans (Skipton) Atom Bank of Ireland (Bristol & West) Bank of Scotland (Lloyds) Barclays Barnsley Building Society (YBS) Bath Building Society Beverley Building Society Birmingham Midshires (Lloyds Banking Group) Bristol & West (Bank of Ireland) Britannia (Co-op) Buckinghamshire Building Society Capital Home Loans Catholic Building Society (Chelsea) (YBS) Chelsea Building Society (YBS) Cheltenham and Gloucester Building Society (Lloyds) Chesham Building Society (Skipton) Cheshire Building Society (Nationwide) Clydesdale Bank part of Yorkshire Bank Co-operative Bank Derbyshire BS (Nationwide) Dunfermline Building Society (Nationwide) Earl Shilton Building Society Ecology Building Society First Direct (HSBC) First Trust Bank (Allied Irish Banks) Furness Building Society Giraffe (Bristol & West then Bank of Ireland UK ) Halifax (Lloyds) Handelsbanken Hanley Building Society Harpenden Building Society Holmesdale Building Society (Skipton) HSBC ING Direct (Barclays) Intelligent Finance (Lloyds) Ipswich Building Society Lambeth Building Society (Portman then Nationwide) Lloyds Bank Loughborough BS Manchester Building Society Mansfield Building Society Mars Capital Masthaven Bank Monmouthshire Building Society Mortgage Works (Nationwide BS) Nationwide Building Society NatWest Newbury Building Society Newcastle Building Society Norwich and Peterborough Building Society (YBS) Optimum Credit Ltd Penrith Building Society Platform (Co-op) Post Office (Bank of Ireland UK Ltd) Principality -

You Can View the Full Spreadsheet Here

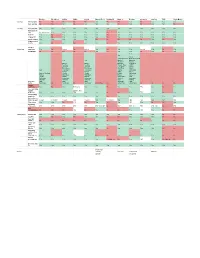

Barclays First Direct Halifax HSBC Lloyds Monzo (Free) Nationwide Natwest Revolut Santander Starling TSB Virgin Money Savings Savings pots No No No No No Yes No No Yes No Yes Yes Yes Auto savings No No Yes No Yes Yes Yes No Yes No Yes Yes No Banking Easy transfer yes Yes yes Yes yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes New payee in app Need debit card Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes New SO Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes change SO Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes pay in cheque Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No No No No No Yes No Yes share account details Yes No yes No yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Analyse Budgeting spending Yes No limited No limited Yes No Yes Yes Limited Yes No Yes Set Budget No No No No No Yes No Yes Yes No Yes No Yes Yes Yes Amex Allied Irish Bank Bank of Scotland Yes Yes Bank of Barclays Scotland Danske Bank of Bank of Barclays First Direct Scotland Scotland Danske Bank HSBC Barclays Barclays First Direct Halifax Barclaycard Barclaycard First Trust Lloyds Yes First Direct First Direct Halifax M&S Bank Halifax Halifax HSBC Monzo Bank of Scotland Lloyds Lloyds Lloyds Nationwide Halifax M&S Bank M&S Bank Monzo Natwest Lloyds MBNA MBNA Nationwide RBS Nationwide Nationwide Nationwide NatWest Santander NatWest NatWest NatWest RBS Starling Add other RBS RBS RBS Santander TSB banks Santander No Santander No Santander Not on free No Ulster Bank Ulster Bank No No No No Instant notifications Yes No Yes Rolling out Yes Yes No Yes Yes TBC Yes No Yes See upcoming regular Balance After payments -

Meet the Exco

Meet the Exco 18th March 2021 Alison Rose Chief Executive Officer 2 Strategic priorities will drive sustainable returns NatWest Group is a relationship bank for a digital world. Simplifying our business to improve customer experience, increase efficiency and reduce costs Supporting Powering our strategy through customers at Powered by Simple to Sharpened every stage partnerships deal with capital innovation, partnership and of their lives & innovation allocation digital transformation. Our Targets Lending c.4% Cost Deploying our capital effectively growth Reduction above market rate per annum through to 20231 through to 20232 CET1 ratio ROTE Building Financial of 13-14% of 9-10% capability by 2023 by 2023 1. Comprises customer loans in our UK and RBS International retail and commercial businesses 2. Total expenses excluding litigation and conduct costs, strategic costs, operating lease depreciation and the impact of the phased 3 withdrawal from the Republic of Ireland Strategic priorities will drive sustainable returns Strengthened Exco team in place Alison Rose k ‘ k’ CEO to deliver for our stakeholders Today, introducing members of the Executive team who will be hosting a deep dive later in the year: David Lindberg 20th May: Commercial Banking Katie Murray Peter Flavel Paul Thwaite CFO CEO, Retail Banking NatWest Markets CEO, Private Banking CEO, Commercial Banking 29th June: Retail Banking Private Banking Robert Begbie Simon McNamara Jen Tippin CEO, NatWest Markets CAO CTO 4 Meet the Exco 5 Retail Banking Strategic Priorities David -

Lender Action Required What Do I Need to Do? Express Payments?

express lender action required what do i need to do? payments? how will i be paid? You can request to be paid within Phone Accord Mortgaegs’ Business Support Team 24 hours of the lender confirming Accord Mortgages Telephone Registration on 03451200866 and ask them to add ‘TMA’as a Yes completion by requesting a payment payment route. through ‘TMA My Portal’. Affirmative Finance will release Registration is required for Affirmative Finance, the payment to TMA on the day of Affirmative No Registration however please state ‘TMA’ when putting a case No completion. TMA will then release Finance through. the payment to the you once it is received. Aldermore products are only available via carefully selected distribution partners. To register to do business with Aldermore go to https;//adlermore- brokerportal.co.uk/MoISiteVisa/Logon/Logon.aspx. You can request to be paid within If you are already registered with Aldermore the on 24 hours of the lender confirming Aldermore Online Registration Yes each case submission you will be asked if you are completion by requesting a submitting business though a Mortgage Club, tick payment through ‘TMA My Portal’. yes and then select ‘TMA’. If TMA is not already in your drop down box then got to ‘Edit Profile’ on the ‘Portal’ and add in ‘TMA’ Please visit us at https://www. Payment will be made every postoffice4intermediaries.co.uk/ and Monday to TMA via BACs. Bank of Ireland Online registration https://www.bankofireland4intermediaries. No Payment is calculated on the first co.uk/ and click register, you will need a Monday 2 weeks after completion profile for each brand. -

Reference Banks / Finance Address

Reference Banks / Finance Address B/F2 Abbey National Plc Abbey House Baker Street LONDON NW1 6XL B/F262 Abbey National Plc Abbey House Baker Street LONDON NW1 6XL B/F57 Abbey National Treasury Services Abbey House Baker Street LONDON NW1 6XL B/F168 ABN Amro Bank 199 Bishopsgate LONDON EC2M 3TY B/F331 ABSA Bank Ltd 52/54 Gracechurch Street LONDON EC3V 0EH B/F175 Adam & Company Plc 22 Charlotte Square EDINBURGH EH2 4DF B/F313 Adam & Company Plc 42 Pall Mall LONDON SW1Y 5JG B/F263 Afghan National Credit & Finance Ltd New Roman House 10 East Road LONDON N1 6AD B/F180 African Continental Bank Plc 24/28 Moorgate LONDON EC2R 6DJ B/F289 Agricultural Mortgage Corporation (AMC) AMC House Chantry Street ANDOVER Hampshire SP10 1DE B/F147 AIB Capital Markets Plc 12 Old Jewry LONDON EC2 B/F290 Alliance & Leicester Commercial Lending Girobank Bootle Centre Bridal Road BOOTLE Merseyside GIR 0AA B/F67 Alliance & Leicester Plc Carlton Park NARBOROUGH LE9 5XX B/F264 Alliance & Leicester plc 49 Park Lane LONDON W1Y 4EQ B/F110 Alliance Trust Savings Ltd PO Box 164 Meadow House 64 Reform Street DUNDEE DD1 9YP B/F32 Allied Bank of Pakistan Ltd 62-63 Mark Lane LONDON EC3R 7NE B/F134 Allied Bank Philippines (UK) plc 114 Rochester Row LONDON SW1P B/F291 Allied Irish Bank Plc Commercial Banking Bankcentre Belmont Road UXBRIDGE Middlesex UB8 1SA B/F8 Amber Homeloans Ltd 1 Providence Place SKIPTON North Yorks BD23 2HL B/F59 AMC Bank Ltd AMC House Chantry Street ANDOVER SP10 1DD B/F345 American Express Bank Ltd 60 Buckingham Palace Road LONDON SW1 W B/F84 Anglo Irish -

Newbuy Guarantee Scheme

1. Please provide a copy of each master policy entered into with (1) Woolwich (2) Santander (3) Halifax (4) Aldermore (5) Nationwide and (6) NatWest under the NewBuy scheme. 2. Please provide a copy of the documentation formally committing the Government to provide the NewBuy Guarantee. 3. Please provide details of any correspondence (including emails) or agreements between HM Treasury and the Financial Services Authority and/or the Prudential Regulation Authority in relation to the use by authorised credit institutions of the master policy as a credit risk mitigant when calculating their regulatory capital requirements. 4. How does the Government account for the NewBuy Guarantee? 5. What reserves does the Government hold against the loans being guaranteed and how does it calculate what these reserves should be? 6. As at the date this request is received, what is the most recent figure that the Government holds for the number of NewBuy loans that are in arrears? And the total number of NewBuy loans? I have considered your request under the terms of the Freedom of Information Act 2000. I confirm that the Department holds some of the information that you have requested, and I am able to supply it to you. Please see an attached copy of the Government Guarantee document formally committing the Government to provide the NewBuy Guarantee. The most recent figures the Department holds on NewBuy are the Official Statistics published on 4th June which show that between 12th March 2012 and 31st March 2013 there were 2291 completions made through the NewBuy Guarantee scheme. Departmental records from lenders show that here was one case of arrears over this period. -

Investor Presentation

Investor Presentation HY 2020 Our Investment Case 1 2 3 4 Our distinctive The scale and A well-positioned Our operational business model & quality of our development expertise & clear strategy portfolio pipeline customer insight Increasing our focus 22.5m sq ft of Development pipeline Expertise in on mixed use places high quality assets aligned to strategy managing and leasing our assets based on our customer insight Growing London Underpinned by our Provides visibility campuses and resilient balance sheet on future earnings Residential and refining and financial strength Drives incremental Retail value for stakeholders 1 British Land at a glance 1FA, Broadgate £15.4bn Assets under management £11.7bn Of which we own £521m Annualised rent 22.5m sq ft Floor space 97% Occupancy Canada Water Plymouth As at September 2019 2 A diverse, high quality portfolio £11.7bn (BL share) Multi-let Retail (26%) London Campuses (45%) 72% London & South East Solus Retail (5%) Standalone offices (10%) Retail – London & SE (10%) Residential & Canada Water (4%) 3 Our unique London campuses £8.6bn Assets under management £6.4bn Of which we own 78% £205m Annualised rent 6.6m sq ft Floor space 97% Occupancy As at September 2019 4 Canada Water 53 acre mixed use opportunity in Central London 5 Why mixed use? Occupiers Employees want space which is… want space which is… Attractive to skilled Flexible Affordable Well connected Located in vibrant Well connected Safe and promotes Sustainable and employees neighbourhoods wellbeing eco friendly Tech Close to Aligned to -

Time to Touch up the CV? Beeb Launches Search for New Director General

BUSINESS WITH PERSONALITY PLOUGHING AHEAD 30 YEARS LATER THE WIMBLEDON LOOK LAND ROVER DISCOVERY TO HEAD BACK TO HITS A LANDMARK P24 MERTON HOME P26 TUESDAY 11 FEBRUARY 2020 ISSUE 3,553 CITYAM.COM FREE HACKED OFF US ramps up China TREASURY TO spat with fresh Equifax charges SET OUT CITY BREXIT PLAN EXCLUSIVE Beyond Brexit, it will also consider “But there will be differences, not CATHERINE NEILAN the industry’s future in relation to least because as a global financial cen- worldwide challenges such as emerg- tre the UK needs to keep pace with @CatNeilan ing technologies and climate change. and drive international standards. THE GOVERNMENT will insist on the Javid sets out the government’s Our starting point will be what’s right right to diverge from EU financial plans to retain regulatory autonomy for the UK.” services regulation as part of a post- while seeking a “reliable equivalence He also re-committed to concluding Brexit trade deal with Brussels. process”, on which a “durable rela- “a full range of equivalence assess- Writing exclusively in City A.M. today, tionship” can be built. ments” by June of this year, in order to chancellor Sajid Javid says the “Of course, each side will only give the system sufficient stability City “will no longer be a rule- grant equivalence if it believes ahead of the end of transition. taker” and reveals that the other’s regulations are One senior industry figure told City ministers are working on compatible,” the chancel- A.M. that while a white paper was EMILY NICOLLE Zhiyong, Wang Qian, Xu Ke and Liu Le, a white paper setting lor writes. -

ABBEY NATIONAL TREASURY SERVICES Plc SANTANDER UK Plc

THIS NOTICE IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION. IF YOU ARE IN ANY DOUBT AS TO THE ACTION YOU SHOULD TAKE, YOU ARE RECOMMENDED TO SEEK YOUR OWN FINANCIAL ADVICE IMMEDIATELY FROM YOUR STOCKBROKER, BANK MANAGER, SOLICITOR, ACCOUNTANT OR OTHER INDEPENDENT FINANCIAL ADVISER WHO, IF YOU ARE TAKING ADVICE IN THE UNITED KINGDOM, IS DULY AUTHORISED UNDER THE FINANCIAL SERVICES AND MARKETS ACT 2000. ABBEY NATIONAL TREASURY SERVICES plc SANTANDER UK plc NOTICE to the holders of the outstanding series of notes listed in the Schedule hereto (the Notes) issued under the Euro Medium Term Note Programme of Abbey National Treasury Services plc (as Issuer of Senior Notes) and Santander UK plc (formerly Abbey National plc) (as Issuer of Subordinated Notes and Guarantor of Senior Notes issued by Abbey National Treasury Services plc) Proposed transfer to Santander UK plc of the business of Alliance & Leicester plc under Part VII of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN to the holders of the Notes (the Noteholders) of the proposed transfer (the Transfer) of the business of Alliance & Leicester plc (A&L) to Santander UK plc (Santander UK) (formerly Abbey National plc (Abbey)) and the right of any person who believes that they would be adversely affected by the Transfer to appear at the Court (as defined below) hearing and object to it, as further described below. If the Court approves the Transfer, it is expected to take effect from and including 28 May 2010. Background to the Transfer Abbey became part of the Santander Group in 2004 and, in 2008, A&L and the Bradford & Bingley savings business and branches became part of the Santander Group's operations in the UK. -

What's the Best Way to Get in Touch with My Banks?

INVESTIGATION | CONTACTING BANKS What’s the best way to get in touch with my bank? With more than 2,000 branches closing over the past decade, In part, banks and building societies have been cutting costs as a result of the financial has it become harder to access your bank, or do new contact crisis, or prioritising investment in technology methods compensate for the decline in face-to-face service? to get people banking in other ways. To better understand this shift in banking decade ago, if you wanted to pay in a The rapid rate of branch closure is a cause access, we surveyed 14 of the biggest current cheque or withdraw some money, all for concern for 57% of Which? members, account providers to find out how many A it would take was a short walk to your according to our survey of 1,356 people in branches they’d closed or opened between local high street bank branch. But today, the January 2014. However, with 89% of those we 2003 and 2013. We also asked about their same transaction at your nearest branch surveyed having access to online banking and branch network plans for 2014 and beyond. might require a 20-mile drive. 76% using telephone banking, it’s perhaps no HSBC closed the largest percentage – almost Given that the number of bank branches surprise that 42% believe that branch banking 30% were shut between the start of 2003 and on our high streets has almost halved since is becoming obsolete. But do the alternatives the end of 2013 – 458 branches in areas where the late 1980s, that’s hardly surprising. -

Aldermore Group PLC – Report and Accounts for the 18 Month Period To

Aldermore Group PLC Report and Accounts for the 18 month period to 30 June 2018 Aldermore Group PLC Report and Accounts 2017/18 Strategic report Contents Corporate Financial governance statements Board of Directors 27 Statement of Directors’ 61 Executive Committee 28 responsibilities Corporate governance structure 30 Independent auditor’s report 62 Directors’ Report 31 Consolidated financial statements 69 Notes to the consolidated 74 financial statements The Company financial statements 120 Notes to the Company 123 financial statements Strategic report Risk management Introduction 1 The Group’s approach to risk 36 Business overview 6 Risk governance and oversight 38 Financial highlights 7 Principal Risks 41 Chairman’s statement 8 Market overview 10 Our business model 12 Chief Executive Officer’s review 14 Chief Financial Officer’s review 16 Business Finance 19 Retail Finance 21 Central Functions 23 Appendix Corporate responsibility 24 Glossary 127 Follow us @AldermoreBank AldermoreBank company/aldermore-bank-plc AldermoreBank For more information on our business visit www.aldermore.co.uk Aldermore Group PLC Report and Accounts 2017/18 1 We are Aldermore Strategic report Strategic Corporate governance Risk management Risk Aldermore helps customers seek We’re not like traditional high- and seize opportunities in their street banks. We go beyond their Financial statements Financial professional and personal lives. one-size fits all approach by understanding our customers’ We provide business financing to circumstances and by making sure support the growth of UK small we offer a high quality service. and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) and we support investors Following a cash offer of 313 pence and home-buyers with per ordinary share for the Group Appendix mortgage finance on property. -

Corporate Governance Risk Management Financial Statements Appendices

39 Strategic report Corporate governance Risk management Financial statements Appendices Corporate governance Chairman’s introduction 40 Board of Directors 42 Executive Committee 44 Corporate governance structure 45 The Board - roles and processes 46 Relations with shareholders 58 Corporate Governance and Nomination Committee Report 60 Audit Committee Report 62 Risk Committee Report 70 Remuneration Report 74 Directors' Report 100 40 Aldermore Group PLC Annual Report and Accounts 2016 Corporate governance Chairman’s introduction 2016 has been a year of consolidation and evolution as we have strived to build on a strong governance framework that we established in preparation for our listing.” Danuta Gray, Interim Chairman UK Corporate Governance Code 2014 (“the Code”) – statement of compliance The Board is committed to the highest standards of corporate governance and confirms that, during the year under review, the Group has complied with the requirements of the Code, which sets out principles relating to the good governance of companies. Following the resignation of Glyn Jones as Chairman with effect from 6 February 2017, and the subsequent appointment of Danuta Gray as Interim Chairman, Danuta Gray is currently not discharging her role as Senior Independent Director. These responsibilities will be resumed on appointment of a new Chairman. The Code is available at www.frc.org.uk This corporate governance report describes how the Board has applied the principles of the Code and provides a clear and comprehensive description of the Group’s governance arrangements. 41 Strategic report Corporate governance Risk management Financial statements Appendices Dear Shareholder Director in October 2016 subsequent brand. During the year, the Executive As your Interim Chairman, I am to him resigning from AnaCap.