1 an Evolutionary Perspective on the British Banking Crisis Abstract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reference Banks / Finance Address

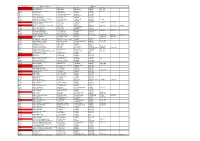

Reference Banks / Finance Address B/F2 Abbey National Plc Abbey House Baker Street LONDON NW1 6XL B/F262 Abbey National Plc Abbey House Baker Street LONDON NW1 6XL B/F57 Abbey National Treasury Services Abbey House Baker Street LONDON NW1 6XL B/F168 ABN Amro Bank 199 Bishopsgate LONDON EC2M 3TY B/F331 ABSA Bank Ltd 52/54 Gracechurch Street LONDON EC3V 0EH B/F175 Adam & Company Plc 22 Charlotte Square EDINBURGH EH2 4DF B/F313 Adam & Company Plc 42 Pall Mall LONDON SW1Y 5JG B/F263 Afghan National Credit & Finance Ltd New Roman House 10 East Road LONDON N1 6AD B/F180 African Continental Bank Plc 24/28 Moorgate LONDON EC2R 6DJ B/F289 Agricultural Mortgage Corporation (AMC) AMC House Chantry Street ANDOVER Hampshire SP10 1DE B/F147 AIB Capital Markets Plc 12 Old Jewry LONDON EC2 B/F290 Alliance & Leicester Commercial Lending Girobank Bootle Centre Bridal Road BOOTLE Merseyside GIR 0AA B/F67 Alliance & Leicester Plc Carlton Park NARBOROUGH LE9 5XX B/F264 Alliance & Leicester plc 49 Park Lane LONDON W1Y 4EQ B/F110 Alliance Trust Savings Ltd PO Box 164 Meadow House 64 Reform Street DUNDEE DD1 9YP B/F32 Allied Bank of Pakistan Ltd 62-63 Mark Lane LONDON EC3R 7NE B/F134 Allied Bank Philippines (UK) plc 114 Rochester Row LONDON SW1P B/F291 Allied Irish Bank Plc Commercial Banking Bankcentre Belmont Road UXBRIDGE Middlesex UB8 1SA B/F8 Amber Homeloans Ltd 1 Providence Place SKIPTON North Yorks BD23 2HL B/F59 AMC Bank Ltd AMC House Chantry Street ANDOVER SP10 1DD B/F345 American Express Bank Ltd 60 Buckingham Palace Road LONDON SW1 W B/F84 Anglo Irish -

Trapped Borrowers and UK Asset Resolution

HM Treasury, 1 Horse Guards Road, London, SW1 A 2HQ Nicky Morgan MP Chair of the Treasury Select Committee House of Commons London SW1A OAA 1zu, November 2018 Trapped Borrowers and UK Asset Resolution During my testimony on 30 October, I promised to write to the Committee to set out the Government's position on "mortgage prisoners", and Tom Scholar committed during his testimony on 24 October to write on the same issue and customer treatment in the context of UK Asset Resolution (UKAR) sales. This letter sets out the Government's position on these issues and covers the issues the Committee raised both with me and with Tom Scholar and Charles Roxburgh. Trapped Borrowers I agree wholeheartedly that borrowers who find themselves unable to access cheaper mortgage deals are in a difficult and stressful situation. While it is right and sensible that regulation since the financial crisis has put an end to the poor lending practices of the past, better deals should not be beyond the reach of customers who are continuing to pay their mortgage. That is why, as part of the reforms to mortgage lending introduced by the Financial Conduct Authority's (FCA) 'Mortgage Market Review' (MMR) in April 2014, lenders were able to waive affordability requirements for new and existing customers that were remortgaging but not increasing the size of their debt. These exemptions were put in place to help existing borrowers who had taken out large mortgages and may have found it more difficult to remortgage under the new rules. Unfortunately, the European Union's (EU) Mortgage Credit Directive (MCD), which came into force in March 2016, formally prevents lenders from waiving the affordability requirements when a borrower moves to a new lender. -

ABBEY NATIONAL TREASURY SERVICES Plc SANTANDER UK Plc

THIS NOTICE IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION. IF YOU ARE IN ANY DOUBT AS TO THE ACTION YOU SHOULD TAKE, YOU ARE RECOMMENDED TO SEEK YOUR OWN FINANCIAL ADVICE IMMEDIATELY FROM YOUR STOCKBROKER, BANK MANAGER, SOLICITOR, ACCOUNTANT OR OTHER INDEPENDENT FINANCIAL ADVISER WHO, IF YOU ARE TAKING ADVICE IN THE UNITED KINGDOM, IS DULY AUTHORISED UNDER THE FINANCIAL SERVICES AND MARKETS ACT 2000. ABBEY NATIONAL TREASURY SERVICES plc SANTANDER UK plc NOTICE to the holders of the outstanding series of notes listed in the Schedule hereto (the Notes) issued under the Euro Medium Term Note Programme of Abbey National Treasury Services plc (as Issuer of Senior Notes) and Santander UK plc (formerly Abbey National plc) (as Issuer of Subordinated Notes and Guarantor of Senior Notes issued by Abbey National Treasury Services plc) Proposed transfer to Santander UK plc of the business of Alliance & Leicester plc under Part VII of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN to the holders of the Notes (the Noteholders) of the proposed transfer (the Transfer) of the business of Alliance & Leicester plc (A&L) to Santander UK plc (Santander UK) (formerly Abbey National plc (Abbey)) and the right of any person who believes that they would be adversely affected by the Transfer to appear at the Court (as defined below) hearing and object to it, as further described below. If the Court approves the Transfer, it is expected to take effect from and including 28 May 2010. Background to the Transfer Abbey became part of the Santander Group in 2004 and, in 2008, A&L and the Bradford & Bingley savings business and branches became part of the Santander Group's operations in the UK. -

Investment Funds and Asset Management Contents

Investment funds and asset management Contents Introduction to our capabilities in the sector 1 An overview of our practice 2 Investment funds 4 M&A in asset management 6 Global investigations, regulatory and taxation 8 Real estate and infrastructure investment 12 Debt investment and financing 14 Our leading position in the sector 16 Our lead sector contacts 18 Our lead specialist contacts for the sector 20 Very good service; they go the extra mile for us. I never have any doubts that they put my interest as a client first. I always have the impression that they’re there fighting my corner. Chambers UK, 2015 Introduction to our capabilities in the sector Slaughter and May has a leading specialist We look forward to discussing how we can investment funds and asset management practice, best support you. If you have any questions, which forms part of our Financial Institutions please contact: Group. We are well known for providing global coverage and market leading advice on bespoke, Robert Chaplin, Partner high value and complex projects. T +44 (0)20 7090 3202 E [email protected] We advise integrated financial institutions, traditional and alternative asset managers, banks, Paul Dickson, Partner insurers, investment funds and the providers of T +44 (0)20 7090 3424 related services. E [email protected] Our capabilities in the sector are focussed on four Robin Ogle, Partner main areas: T +44 (0)20 7090 3118 E [email protected] • Mergers, acquisitions, formations and reorganisations of asset management Slaughter and May businesses and transactions in fund assets One Bunhill Row, London EC1Y 8YY. -

Aldermore Group PLC – Report and Accounts for the 18 Month Period To

Aldermore Group PLC Report and Accounts for the 18 month period to 30 June 2018 Aldermore Group PLC Report and Accounts 2017/18 Strategic report Contents Corporate Financial governance statements Board of Directors 27 Statement of Directors’ 61 Executive Committee 28 responsibilities Corporate governance structure 30 Independent auditor’s report 62 Directors’ Report 31 Consolidated financial statements 69 Notes to the consolidated 74 financial statements The Company financial statements 120 Notes to the Company 123 financial statements Strategic report Risk management Introduction 1 The Group’s approach to risk 36 Business overview 6 Risk governance and oversight 38 Financial highlights 7 Principal Risks 41 Chairman’s statement 8 Market overview 10 Our business model 12 Chief Executive Officer’s review 14 Chief Financial Officer’s review 16 Business Finance 19 Retail Finance 21 Central Functions 23 Appendix Corporate responsibility 24 Glossary 127 Follow us @AldermoreBank AldermoreBank company/aldermore-bank-plc AldermoreBank For more information on our business visit www.aldermore.co.uk Aldermore Group PLC Report and Accounts 2017/18 1 We are Aldermore Strategic report Strategic Corporate governance Risk management Risk Aldermore helps customers seek We’re not like traditional high- and seize opportunities in their street banks. We go beyond their Financial statements Financial professional and personal lives. one-size fits all approach by understanding our customers’ We provide business financing to circumstances and by making sure support the growth of UK small we offer a high quality service. and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) and we support investors Following a cash offer of 313 pence and home-buyers with per ordinary share for the Group Appendix mortgage finance on property. -

Annual Financial Report

Annual Financial Report Released : 05/06/2019 07:00:00 RNS Number : 1454B NRAM Ltd 05 June 2019 NRAM Limited 05 June 2019 RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT NRAM Limited ('the Company') today issues its results for the year ended 31 March 2019. The Company is a subsidiary of UK Asset Resolution Limited ('UKAR'), the holding company established in 2010 to facilitate the orderly management of the closed mortgage books of both NRAM plc and Bradford & Bingley plc ('B&B'). The Company's full Annual Report & Accounts are available to view today on the UK Asset Resolution Limited website at www.ukar.co.uk/nram. The Annual Report & Accounts have also been submitted to the National Storage Mechanism and will shortly be available for inspection at www.morningstar.co.uk/uk/NSM. The Company is registered in England and Wales under company number 09655526. The Company and its subsidiary undertakings comprise the NRAM Limited Group. Overview The NRAM Limited Group and Company primarily operates as an asset manager holding mortgage loans secured on residential properties and other financial assets. No new lending is carried out. NRAM plc was taken into public ownership on 22 February 2008. During 2007 and 2008 loan facilities to NRAM plc were put in place by the Bank of England all of which were novated to Her Majesty's Treasury ('HM Treasury') on 28 August 2008. On 28 October 2009 the European Commission approved State aid to NRAM plc confirming the facilities provided by HM Treasury, thereby removing the material uncertainty over NRAM plc's ability to continue as a going concern which previously existed. -

Corporate Governance Risk Management Financial Statements Appendices

39 Strategic report Corporate governance Risk management Financial statements Appendices Corporate governance Chairman’s introduction 40 Board of Directors 42 Executive Committee 44 Corporate governance structure 45 The Board - roles and processes 46 Relations with shareholders 58 Corporate Governance and Nomination Committee Report 60 Audit Committee Report 62 Risk Committee Report 70 Remuneration Report 74 Directors' Report 100 40 Aldermore Group PLC Annual Report and Accounts 2016 Corporate governance Chairman’s introduction 2016 has been a year of consolidation and evolution as we have strived to build on a strong governance framework that we established in preparation for our listing.” Danuta Gray, Interim Chairman UK Corporate Governance Code 2014 (“the Code”) – statement of compliance The Board is committed to the highest standards of corporate governance and confirms that, during the year under review, the Group has complied with the requirements of the Code, which sets out principles relating to the good governance of companies. Following the resignation of Glyn Jones as Chairman with effect from 6 February 2017, and the subsequent appointment of Danuta Gray as Interim Chairman, Danuta Gray is currently not discharging her role as Senior Independent Director. These responsibilities will be resumed on appointment of a new Chairman. The Code is available at www.frc.org.uk This corporate governance report describes how the Board has applied the principles of the Code and provides a clear and comprehensive description of the Group’s governance arrangements. 41 Strategic report Corporate governance Risk management Financial statements Appendices Dear Shareholder Director in October 2016 subsequent brand. During the year, the Executive As your Interim Chairman, I am to him resigning from AnaCap. -

Living in a 1% World

LivingLiving inin aa 1%1% WorldWorld FredFred GoodwinGoodwin GroupGroup ChiefChief ExecutiveExecutive Slide 2 Living in a 1% World 1% World Stakeholder pensions Sandler regulated products Slide 3 Living in a 1% World Implications for RBS Lower margins on long term savings Less than 1% of RBS income from long term savings Higher volumes of distribution of long term savings Simpler products, processes better for bank distribution Slide 4 Living in a 1% World What are the required characteristics for growth? Slide 5 Required Characteristics for Growth Organic growth – Large distribution capacity – Multiple brands – Low market shares – Effective sales processes – Able to grow new businesses – Diversity of income Acquisitions – Able to make good acquisitions – Good at integration of acquisitions Efficiency – Able to improve efficiency Slide 6 Large Distribution Capacity Distribution Channels UK Ranking Branches #1 Supermarkets #1 Telephone #1 = Internet #? (large) ATMs #1 Relationship Managers #1 Source: Company Accounts, CACI and Link Slide 7 Multiple Brands Multi-Brand, Multiple Channel Strategy Slide 8 Multiple Brands Multi-Brand, Multiple Channel Strategy Appeals to different customer groups Allows different product variants, pricing Gives flexibility for future Allows management autonomy Slide 9 Low Market Shares UK Market Shares Total RBS Current accounts 21% Savings accounts 8% Personal loans 10% Mortgages 5% Credit cards 17% Life insurance 2% Motor insurance 16%* Home insurance 13%* Small business relationships 30% -

Abbey National Treasury Services Plc Santander UK

SUPPLEMENT DATED 10 AUGUST 2010 TO THE PROSPECTUSES SET OUT IN THE SCHEDULE HERETO Abbey National Treasury Services plc (incorporated in England and Wales with limited liability, registered number 2338548) Unconditionally guaranteed by Santander UK plc (formerly Abbey National plc) (incorporated in England and Wales with limited liability, registered number 2294747) The Prospectuses listed in the schedule hereto This supplement (the “Supplement”, which definition shall also include all information incorporated by reference herein) to the Prospectus dated 8 September 2009, the Prospectus dated 16 December 2009, the Prospectus dated 14 April 2010 and the Prospectus dated 5 May 2010 listed in the Schedule hereto (each as supplemented at the date hereof) (the “Prospectuses”) (each of which comprises a base prospectus for the purpose of Article 5.4 of Directive 2003/71/EC (the “Prospectus Directive”)), constitutes a supplementary prospectus for the purposes of Section 87G of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (“FSMA”). Terms defined in the Prospectuses have the same meaning when used in this Supplement. This Supplement is supplemental to, and should be read in conjunction with the Prospectuses and any other supplements to the Prospectuses issued by Abbey National Treasury Services plc, as Issuer on the Covered Bond Programme, the Structured Note Programme, the Warrant Programme and the EMTN Programme and Santander UK plc who is also an Issuer for the EMTN programme, (together the “Issuers”) (each as defined in the Schedule). This Supplement has been approved by the United Kingdom Financial Services Authority (the “FSA”), which is the United Kingdom competent authority for the purposes of the Prospectus Directive and relevant implementing measures in the United Kingdom for the purpose of giving information with regard to the issue of instruments under each of the programmes described in the Prospectus. -

B21448 R&A 2008 Front

B21448 R&A 2008 FRONT 23/3/09 13:33 Page 1 Annual Report & Accounts 2008 B21448 R&A 2008 FRONT 23/3/09 13:33 Page 1 Bradford & Bingley Annual Report & Accounts 2008 01 Contents Directors’ report 02 Chairman’s statement 03 Introduction 05 Business review 07 Key performance indicators 08 Financial review 14 Our Board 16 Corporate governance 19 Risk management and control 23 Directors’ remuneration report 30 Corporate social responsibility 31 Statement of Directors’ responsibilities 32 Other matters The accounts 36 Independent Auditor’s report 37 Consolidated income statement 38 Balance sheets 39 Statements of recognised income and expense 40 Cash flow statements 41 Notes to the financial statements B21448 R&A 2008 FRONT 3/4/09 10:45 Page 2 Bradford & Bingley Annual Report & Accounts 2008 02 Directors’ report Chairman’s statement 2008 was a turbulent year for British banks, and a very disappointing year for Bradford & Bingley. Against a deteriorating economic background, which first became apparent in the third quarter of 2007, the Board took a series of prudent financial decisions to dispose of non-core lending portfolios, to raise committed, secured wholesale funding facilities and to seek additional capital via a rights issue. I joined Bradford & Bingley as Chief Executive on 18 August 2008, the day on which the rights issue closed, and set about addressing some of the operational issues that needed attention. We cut mortgage sales capacity further; reduced our commitments to third party mortgage providers; increased our sales focus on retail deposits; tackled our costs; addressed balance sheet risk; and intensified our efforts in mortgage arrears collections. -

Firm Foundations

Report & Accounts 2007 18/3/08 2:56 pm Page 1 Annual Report and Accounts 2007 Firm Foundations Principal Office: Portland House, New Bridge Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 8AL. Telephone: (0191) 244 2000 Newcastle Building Society Report & Accounts 2007 18/3/08 2:56 pm Page 3 CONTENTS Our vision Our vision 3 We aim to be a friendly, caring organisation that values customer loyalty, gives value for money and contributes Chairman’s Statement 4 to the current and future wellbeing of the community. We recognise that our members and customers, Chief Executive’s Review 5 employees and the communities we serve all have a part to play in the future of the Society. We believe we can Finance Director’s Report 8 best serve the interests of all three by remaining a strong, dynamic and independent mutual building society. Our Directors 10 Our objectives for each are: Directors’ Report 12 OUR MEMBERS AND CUSTOMERS Report of the Directors on Corporate Governance 14 I To provide a secure home for savings; Remuneration Committee Report 16 I To provide a range of innovative and competitively priced mortgage, savings, investment and Risk Management Report 18 insurance products; Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities 19 I To be a customer focused organisation which understands its customers and listens to what they say; Independent Auditors’ Report 20 I To offer expert and trusted advice on good value products across a range of services; Income Statements 21 Statements of Recognised Income and Expense 21 I To provide effective customer service in a prompt, courteous and efficient manner; Balance Sheets 22 I To treat customers fairly and in a way that is consistent with mutuality; Cash Flow Statements 24 I To provide effective solutions by sharing our technology and innovation with our business partners; Notes to the Accounts 25 I To treat our business partner customers with the same integrity and professionalism with which we Annual Business Statement 53 treat our members. -

U.K. Asset Resolution Limited (UKAR)

PRELIMINARY YPFS DISCUSSION DRAFT| MARCH 2020 U.K. Asset Resolution Limited (UKAR) Aidan Lawson1 August 23, 2019 Abstract As the Global Financial Crisis began to unfold, the UK saw two of its largest mortgage lenders in Bradford & Bingley (B&B) and Northern Rock, begin to weaken dramatically under the pressure that housing and financial markets were facing. Northern Rock and B&B both faced severe funding problems due to a worsening global credit crunch and both would be nationalized in 2008 (NRAM; B&B). Despite this effort, the crisis continued to worsen globally, and, amongst other programs that the UK government instituted, it created UK Asset Resolution Limited (UKAR) on October 1, 2010 (UKAR Overview). This organization’s goal was to wind down and maximize the return on the £115.8 billion in closed mortgage books that the government still had from B&B and what was now Northern Rock Asset Management (2019 Annual Report - pp. 11). In order to adequately manage UKAR’s massive portfolio of residential and commercial loans, mortgage-backed securities, and derivative instruments, HM Treasury and the Financial Services Compensation Scheme (FSCS) provided £48.7 billion in funding to the company (2011 Annual Report - pp. 16). Through a mix of large, competitive sales, buy-backs, and loan redemptions, UKAR consistently has been able to reduce its balance sheet and turn a profit every year since its inception (2018 Annual Report - pp. 14, 21). As of June 2019, the company has made approximately £8.1 billion in profit and has only £11.4 billion in assets remaining on its balance sheet (2019 Annual Report - pp.