Illiberal Democracies in the EU: the Visegrad Group and the Risk of Disintegration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PSCI 5113 / EURR 5113 Democracy in the European Union Mondays, 11:35 A.M

Carleton University Fall 2019 Department of Political Science Institute of European, Russian and Eurasian Studies PSCI 5113 / EURR 5113 Democracy in the European Union Mondays, 11:35 a.m. – 2:25 p.m. Please confirm location on Carleton Central Instructor: Professor Achim Hurrelmann Office: D687 Loeb Building Office Hours: Mondays, 3:00 p.m. – 4:00 p.m., and by appointment Phone: (613) 520-2600 ext. 2294 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @achimhurrelmann Course description: Over the past seventy years, European integration has made significant contributions to peace, economic prosperity and cultural exchange in Europe. By contrast, the effects of integration on the democratic quality of government have been more ambiguous. The European Union (EU) possesses more mechanisms of democratic input than any other international organization, most importantly the directly elected European Parliament (EP). At the same time, the EU’s political processes are often described as insufficiently democratic, and European integration is said to have undermined the quality of national democracy in the member states. Concerns about a “democratic deficit” of the EU have not only been an important topic of scholarly debate about European integration, but have also constituted a major argument of populist and Euroskeptic political mobilization, for instance in the “Brexit” referendum. This course approaches democracy in the EU from three angles. First, it reviews the EU’s democratic institutions and associated practices of citizen participation: How -

One Child, One Vote: Proxies for Parents Jane Rutherford

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Minnesota Law Review 1998 One Child, One Vote: Proxies for Parents Jane Rutherford Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Rutherford, Jane, "One Child, One Vote: Proxies for Parents" (1998). Minnesota Law Review. 1582. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr/1582 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Minnesota Law Review collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. One Child, One Vote: Proxies for Parents Jane Rutherford* Introduction .............................................................................1464 I. Autonomy as a Source of Rights ...................................... 1467 A. A Power-Based Critique ........................................... 1468 B. A Communitarian Critique ...................................... 1474 H. Preserving the Right to Vote for Insiders by Focusing on the Incapacity of Outsiders ......................... 1479 III. Children's Rights ............................................................. 1489 A. Greater Autonomy for Children .............................. 1490 B. Substantive Entitlements for Children ................... 1493 C. The Value of the Vote for Children .......................... 1494 IV. One Child, One Vote: Proxy Voting For Children .......... 1495 A. Political Power -

November 2020

EPP Party Barometer November 2020 The Situation of the European People’s Party in the EU (as of: 23 November 2020) Dr Olaf Wientzek (Graphic template: Janine www.kas.de Höhle, HA Kommunikation, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung) Summary & latest developments (I) • In national polls, the EPP family are the strongest political family in 12 countries (including Fidesz); the Socialist political family in 6, the Liberals/Renew in 4, far-right populists (ID) in 2, and the Eurosceptic/national conservative ECR in 1. Added together, independent parties lead in Latvia. No polls/elections have taken place in France since the EP elections. • The picture is similar if we look at the strongest single party and not the largest party family: then the EPP is ahead in 12 countries (if you include the suspended Fidesz), the Socialists in 7, the Liberals in 4, far-right populists (ID) in 2, and the ECR in one land. • 10 (9 without Orbán) of the 27 Heads of State and Government in the European Council currently belong to the EPP family, 7 to the Liberals/Renew, 6 to the Social Democrats / Socialists, 1 to the Eurosceptic conservatives, and 2 are formally independent. The party of the Slovak head of government belongs to the EPP group but not (yet) to the EPP party; if you include him in the EPP family, there would be 11 (without Orbán 10). • In many countries, the lead is extremely narrow, or, depending on the polls, another party family is ahead (including Italy, Sweden, Latvia, Belgium, Poland). Summary & latest developments (II) • In Romania, the PNL (EPP) has a good starting position for the elections (Dec. -

Wien Institute for Advanced Studies, Vienna

Institut für Höhere Studien (IHS), Wien Institute for Advanced Studies, Vienna Reihe Politikwissenschaft / Political Science Series No. 45 The End of the Third Wave and the Global Future of Democracy Larry Diamond 2 — Larry Diamond / The End of the Third Wave — I H S The End of the Third Wave and the Global Future of Democracy Larry Diamond Reihe Politikwissenschaft / Political Science Series No. 45 July 1997 Prof. Dr. Larry Diamond Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 USA e-mail: [email protected] and International Forum for Democratic Studies National Endowment for Democracy 1101 15th Street, NW, Suite 802 Washington, DC 20005 USA T 001/202/293-0300 F 001/202/293-0258 Institut für Höhere Studien (IHS), Wien Institute for Advanced Studies, Vienna 4 — Larry Diamond / The End of the Third Wave — I H S The Political Science Series is published by the Department of Political Science of the Austrian Institute for Advanced Studies (IHS) in Vienna. The series is meant to share work in progress in a timely way before formal publication. It includes papers by the Department’s teaching and research staff, visiting professors, students, visiting fellows, and invited participants in seminars, workshops, and conferences. As usual, authors bear full responsibility for the content of their contributions. All rights are reserved. Abstract The “Third Wave” of global democratization, which began in 1974, now appears to be drawing to a close. While the number of “electoral democracies” has tripled since 1974, the rate of increase has slowed every year since 1991 (when the number jumped by almost 20 percent) and is now near zero. -

The Battle Between Secularism and Islam in Algeria's Quest for Democracy

Pluralism Betrayed: The Battle Between Secularism and Islam in Algeria's Quest for Democracy Peter A. Samuelsont I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................... 309 f1. BACKGROUND TO THE ELECTIONS AND THE COUP ................................ 311 A. Algeria's Economic Crisis ......................................... 311 B. Algeria's FirstMultiparty Elections in 1990 for Local Offices ................ 313 C. The FIS Victory in the 1991 ParliamentaryElections ...................... 314 D. The Coup dt& tat ................................................ 318 E. Western Response to the Coup ...................................... 322 III. EVALUATING THE LEGITIMACY OF THE COUP ................................ 325 A. Problems Presented by Pluralism .................................... 326 B. Balancing Majority Rights Against Minority Rights ........................ 327 C. The Role of Religion in Society ...................................... 329 D. Islamic Jurisprudence ............................................ 336 1. Islamic Views of Democracy and Pluralism ......................... 337 2. Islam and Human Rights ...................................... 339 IV. PROBABLE ACTIONS OF AN FIS PARLIAMENTARY MAJORITY ........................ 340 A. The FIS Agenda ................................................ 342 1. Trends Within the FIS ........................................ 342 2. The Process of Democracy: The Allocation of Power .................. 345 a. Indicationsof DemocraticPotential .......................... 346 -

2019 © Timbro 2019 [email protected] Layout: Konow Kommunikation Cover: Anders Meisner FEBRUARY 2019

TIMBRO AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM INDEX 2019 © Timbro 2019 www.timbro.se [email protected] Layout: Konow Kommunikation Cover: Anders Meisner FEBRUARY 2019 ABOUT THE TIMBRO AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM INDEX Authoritarian Populism has established itself as the third ideological force in European politics. This poses a long-term threat to liberal democracies. The Timbro Authoritarian Populism Index (TAP) continuously explores and analyses electoral data in order to improve the knowledge and understanding of the development among politicians, media and the general public. TAP contains data stretching back to 1980, which makes it the most comprehensive index of populism in Europe. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • 26.8 percent of voters in Europe – more than one in four – cast their vote for an authoritarian populist party last time they voted in a national election. • Voter support for authoritarian populists increased in all six elections in Europe during 2018 and has on an aggregated level increased in ten out of the last eleven elections. • The combined support for left- and right-wing populist parties now equals the support for Social democratic parties and is twice the size of support for liberal parties. • Right-wing populist parties are currently growing more rapidly than ever before and have increased their voter support with 33 percent in four years. • Left-wing populist parties have stagnated and have a considerable influence only in southern Europe. The median support for left-wing populist in Europe is 1.3 percent. • Extremist parties on the left and on the right are marginalised in almost all of Europe with negligible voter support and almost no political influence. -

Codebook Indiveu – Party Preferences

Codebook InDivEU – party preferences European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies December 2020 Introduction The “InDivEU – party preferences” dataset provides data on the positions of more than 400 parties from 28 countries1 on questions of (differentiated) European integration. The dataset comprises a selection of party positions taken from two existing datasets: (1) The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File contains party positions for three rounds of European Parliament elections (2009, 2014, and 2019). Party positions were determined in an iterative process of party self-placement and expert judgement. For more information: https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/65944 (2) The Chapel Hill Expert Survey The Chapel Hill Expert Survey contains party positions for the national elections most closely corresponding the European Parliament elections of 2009, 2014, 2019. Party positions were determined by expert judgement. For more information: https://www.chesdata.eu/ Three additional party positions, related to DI-specific questions, are included in the dataset. These positions were determined by experts involved in the 2019 edition of euandi after the elections took place. The inclusion of party positions in the “InDivEU – party preferences” is limited to the following issues: - General questions about the EU - Questions about EU policy - Questions about differentiated integration - Questions about party ideology 1 This includes all 27 member states of the European Union in 2020, plus the United Kingdom. How to Cite When using the ‘InDivEU – Party Preferences’ dataset, please cite all of the following three articles: 1. Reiljan, Andres, Frederico Ferreira da Silva, Lorenzo Cicchi, Diego Garzia, Alexander H. -

THE RISE of COMPETITIVE AUTHORITARIANISM Steven Levitsky and Lucan A

Elections Without Democracy THE RISE OF COMPETITIVE AUTHORITARIANISM Steven Levitsky and Lucan A. Way Steven Levitsky is assistant professor of government and social studies at Harvard University. His Transforming Labor-Based Parties in Latin America is forthcoming from Cambridge University Press. Lucan A. Way is assistant professor of political science at Temple University and an academy scholar at the Academy for International and Area Studies at Harvard University. He is currently writing a book on the obstacles to authoritarian consolidation in the former Soviet Union. The post–Cold War world has been marked by the proliferation of hy- brid political regimes. In different ways, and to varying degrees, polities across much of Africa (Ghana, Kenya, Mozambique, Zambia, Zimbab- we), postcommunist Eurasia (Albania, Croatia, Russia, Serbia, Ukraine), Asia (Malaysia, Taiwan), and Latin America (Haiti, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru) combined democratic rules with authoritarian governance during the 1990s. Scholars often treated these regimes as incomplete or transi- tional forms of democracy. Yet in many cases these expectations (or hopes) proved overly optimistic. Particularly in Africa and the former Soviet Union, many regimes have either remained hybrid or moved in an authoritarian direction. It may therefore be time to stop thinking of these cases in terms of transitions to democracy and to begin thinking about the specific types of regimes they actually are. In recent years, many scholars have pointed to the importance of hybrid regimes. Indeed, recent academic writings have produced a vari- ety of labels for mixed cases, including not only “hybrid regime” but also “semidemocracy,” “virtual democracy,” “electoral democracy,” “pseudodemocracy,” “illiberal democracy,” “semi-authoritarianism,” “soft authoritarianism,” “electoral authoritarianism,” and Freedom House’s “Partly Free.”1 Yet much of this literature suffers from two important weaknesses. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

European Populism in the European Union

H Balnaves, E Monteiro Burkle, J Erkan & D Fischer ‘European populism in the European Union: Results and human rights impacts of the 2019 parliamentary elections’ (2020) 4 Global Campus Human Rights Journal 176-200 http://doi.org/20.500.11825/1695 European populism in the European Union: Results and human rights impacts of the 2019 parliamentary elections Hugo Balnaves,* Eduardo Monteiro Burkle,** Jasmine Erkan*** and David Fischer**** Abstract: Populism is a problem neither unique nor new to Europe. However, a number of crises within the European Union, such as the ongoing Brexit crisis, the migration crisis, the climate crisis and the rise of illiberal regimes in Eastern Europe, all are adding pressure on EU institutions. The European parliamentary elections of 2019 saw a significant shift in campaigning, results and policy outcomes that were all affected by, inter alia, the aforementioned crises. This article examines the theoretical framework behind right-wing populism and its rise in Europe, and the role European populism has subversively played in the 2019 elections. It examines the outcomes and human rights impacts of the election analysing the effect of right-wing populists on key EU policy areas such as migration and climate change. Key Words: European parliamentary elections; populism; EU institutions; human rights * LLB (University of Adelaide) BCom (Marketing) (University of Adelaide); EMA Student 2019/20. ** LLB (State University of Londrina); EMA Student 2019/20. *** BA (University of Western Australia); EMA Student 2019/20. **** MA (University of Mainz); EMA Student 2019/20. European populism in the European Union 177 1 Introduction 2019 was a year fraught with many challenges for the European Union (EU) as it continued undergoing several crises, including the ongoing effects of Brexit, the migration crisis, the climate crisis and the rise of illiberal regimes in Eastern Europe. -

List of Members

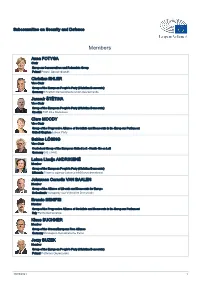

Subcommittee on Security and Defence Members Anna FOTYGA Chair European Conservatives and Reformists Group Poland Prawo i Sprawiedliwość Christian EHLER Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Germany Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands Jaromír ŠTĚTINA Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Czechia TOP 09 a Starostové Clare MOODY Vice-Chair Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament United Kingdom Labour Party Sabine LÖSING Vice-Chair Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Germany DIE LINKE. Laima Liucija ANDRIKIENĖ Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Lithuania Tėvynės sąjunga-Lietuvos krikščionys demokratai Johannes Cornelis VAN BAALEN Member Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Netherlands Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie Brando BENIFEI Member Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Italy Partito Democratico Klaus BUCHNER Member Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance Germany Ökologisch-Demokratische Partei Jerzy BUZEK Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Poland Platforma Obywatelska 30/09/2021 1 Aymeric CHAUPRADE Member Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy Group France Les Français Libres Javier COUSO PERMUY Member Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Spain Independiente Arnaud DANJEAN Member Group of the European People's Party -

1 European Demoicracy and Its Crisis1 KALYPSO NICOLAÏDIS

In Journal of Common Market Studies, March 2013, Vol. 51, no. 2, pp. 000-000. European Demoicracy and Its Crisis1 KALYPSO NICOLAÏDIS Abstract This article offers an overview and reconsideration of the idea of European demoicracy in the context of the current crisis. It defines demoicracy as ‘a Union of peoples, understood both as states and as citizens, who govern together but not as one,’ and argues that the concept is best understood as a third way, distinct from both national and supranational versions of single demos polities. The concept of demoicracy can serve both as an analytical lens for the EU-as-is and as a normative benchmark, but one which cannot simply be inferred from its praxis. Instead, the article deploys a ‘normative-inductive’ approach according to which the EU’s normative core - transnational non-domination and transnational mutual recognition - is grounded on what the EU still seeks to escape. Such norms need to be protected and perfected if the EU is to live up to its essence. The article suggests ten tentative guiding principles for the EU to continue turning such norms into practice. _____________________________________________________________________ The aftershock of the 2008 global financial crisis in the EU has come to be widely seen as a crisis of ‘democracy’ in Europe. This article starts from the premise that the EU’s legitimacy deficit will not be addressed by tinkering with its institutions. Instead, the name of the democratic game in Europe today is democratic interdependence: the Union magnifies the pathologies of the national democracies in its midst, even as it entrenches and nurtures these democracies, who in turn affect each other in profound ways.