The Constitutional Right to Community Services, 26 Ga

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Rooming House to Cozy Home

Serving the Glebe community since 1973 www.glebereport.ca ISSN 0702-7796 March 13, 2015 Vol. 43 No. 3 Issue no. 468 FREE ANNER T M to PHOTO: PHOTO: From rooming house to cozy home By Tom Tanner The sorry condition of the Glebe Avenue property should every family need their own washing machine, was not a deal breaker in 1978 when we decided to buy lawn mower or power tools? Co-operative living could We were enthused by the possibilities and prepared to the large semi-detached that operated as a rooming mean help with child care, home renovation and other overlook the reality. Well, almost – the dining room house. An opening between the two sides meant the tasks. Eventually two sets of families actually bought made an impression. The sliding doors to the foyer landlord rented 11 rooms and three apartments. Every homes in the Glebe. Of these four families, we are the were wired shut and there were three locks on the room had at least one lock. When we took possession only ones still living in our (now individualized) com- smaller door. Boxes of empty beer bottles filled the the seller rummaged through the trunk of his car where munal house. alcove and there was a mattress on the floor. But the he kept several boxes full of keys – for our new home The Glebe was quite affordable in the late 1970s. “Do- motorcycle was the biggest surprise; we did not even and his other properties. it-yourself” (DIY) was the watchword. But the Glebe notice the charming china cabinet built into the wall During the 1970s the possibility of shared housing on that side of the room. -

JCHS Alumni Hall of Fame Biographies 2012 - 2020

JCHS Alumni Hall of Fame Biographies 2012 - 2020 JCHS Alumni Hall of Fame 2012 Dr. Ron Brooks - 1997 Graduate Ron graduated from Bellarmine University with a Bachelor of Science degree. He then attended Indiana University School of Medicine followed by a move to New York City where he completed a residency and surgical research program through New York Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical College. Ron has been a shining academic example to his fellow classmates through high school, college and post-graduate level. His determination, hard work and relentless pursuit of academic, personal and professional goals have inspired many. During his surgical research, Brooks studied various aspects of breast cancer and these studies, in conjunction with his professional memberships are continuing to search for a breast cancer cure. Dr. Ron Brooks is currently working as a plastic surgery fellow at the University of Louisville. Rosemary Edens - 1970 Graduate After overcoming some seemingly insurmountable health problems and seeing her own daughters into their school years, Rosemary Edens attended Indiana University as an adult student and earned a Bachelor degree in English with a minor in sociology. She went on to earn a Master’s degree in counseling. In 1988, she came back to Jennings County Schools and proceeded to serve our school district for nearly 22 years. She became well-known for her enthusiasm, her ability to make learning fun, and her ability to reach all of her students. After “retiring” in June 2010, she and husband, Dennis had been enjoying grandkids and John Deere tractors until this past fall when she was recruited to return to JCHS for this school year and is currently teaching sophomore English. -

28, 1964 Paul J

March Is Family Red Cross Month N e w s p a p e r SEVEN CENTS Vol. LXXXIX, No. 9 OCEAN GROVE TIMES, TOWNSHIP OF NEPTUNE. NEW JERSEY, FRIDAY, FEBRUAR 28, 1964 Paul J. Riley VFW Ladies Present American Flag Musicale And Tea Firemen Fete 50-Year Members New Salary Guide Wins Freedom At Woman’s Club Of $4,400 to $8,800 Foundation Award Queensmen Featured For Twp. Teachers In Program To Benefit Scholarship Fund New President Presides V VALLEY FORGE, PA. — And Committee Chairmen Freedoms Foundation at Val Named for 1964-1965 , ley Forge, Pennsylvania, an OCEAN GROVE — The Choral nounced that Paul J. Riley of group of the Womart/s Club of N R P T .U N E — At the Nep- . 4 Steiner : avenue, Neptune Ocean Grove presented a musicale tune Town ship Board of Edu-; ^ City was a principal award tea at the clubhouse last Thursday for the. benefit of the cation meetinfr ‘;at' the' winner of' the 1963 Freedoms mediate School Wednesday ' Foundation awards which are Meta Thorne W aters' Scholarship Fund. The . program featured the night, a teachers’ salary guide ; presented annually to those for 1964-1,965 was adopted.^ persons and groups who help “Queensmen” Rutgers' University quartet.' >.. The schedule was. developed improve public understanding in 13 steps showing steps 1, of the American way of life.' Roy D. Gemberling, manager of the quartet, introduced the three $4400 for non-degree, ^5000V other members: David W. Hardy, for B. A. degree Or 15 / years Richard D. Dahoney and David in Neptune, $5200 for Thaxton. -

Best of 2018 Listener Survey BEST WRESTLER (MALE) Responses to This Question: 419

Best of 2018 Listener Survey BEST WRESTLER (MALE) Responses to this question: 419 96 22.9% Kenny Omega 78 18.6% Johnny Gargano 54 12.9% Seth Rollins 35 8.4% AJ Styles 24 5.7% Tommaso Ciampa 24 5.7% Tomohiro Ishii 21 5.0% Kazuchika Okada 12 2.9% Walter 10 2.4% Hiroshi Tanahashi 7 1.7% Zack Sabre Jr. 6 1.4% Cody Rhodes 5 1.2% Kota Ibushi 5 1.2% Pete Dunne 4 1.0% Daniel Bryan 4 1.0% Will Ospreay 3 0.7% Adam Cole 3 0.7% Chris Jericho 3 0.7% Roman Reigns 3 0.7% Velveteen Dream 2 0.5% Minoru Suzuki 2 0.5% Mustafa Ali 2 0.5% Pentagon Jr. 2 0.5% Samoa Joe 1 0.2% Aleister Black 1 0.2% Braun Strowman 1 0.2% Brock Lesnar 1 0.2% David Starr 1 0.2% Effy 1 0.2% Finn Balor 1 0.2% Gran Metalik 1 0.2% Jay Lethal 1 0.2% Kyle O'Reilly 1 0.2% L.A. Park 1 0.2% R-Trush 1 0.2% Tetsuya Naito 1 0.2% The Miz 1 0.2% Toru Yano BEST WRESTLER (FEMALE) Responses to this question: 418 299 71.5% Becky Lynch 23 5.5% Charlotte Flair 15 3.6% Ronda Rousey 14 3.3% Shayna Baszler 11 2.6% Toni Storm 9 2.2% Kairi Sane 9 2.2% Meiko Satomura 7 1.7% Tessa Blanchard 5 1.2% Momo Watanabe 4 1.0% Alexa Bliss 4 1.0% Asuka 4 1.0% Io Sharai 3 0.7% Mayu Iwatani 2 0.5% Natalya 1 0.2% Chelsea Green 1 0.2% Ember Moon 1 0.2% Isla Dawn 1 0.2% Kagetsu 1 0.2% Madison Eagles 1 0.2% Mickie James 1 0.2% Rosemary 1 0.2% Shida Hikaru 1 0.2% Taya Valkyrie BEST TAG TEAM Responses to this question: 414 159 38.4% Young Bucks 104 25.1% Undisputed Era 24 5.8% Golden Lovers 23 5.6% The Usos 13 3.1% New Day 13 3.1% Usos 10 2.4% Evil & Sanada 9 2.2% LAX 9 2.2% Moustache Mountain 8 1.9% The Bar 5 1.2% Lucha Brothers 3 0.7% Best Friends 3 0.7% Bludgeon Brothers 2 0.5% AOP 2 0.5% Aussie Open 2 0.5% Heavy Machinery 2 0.5% Roppongi 3K 2 0.5% SCU 2 0.5% The Revival 1 0.2% Bandido and Flamita 1 0.2% Bobby Fish and Kyle O'Reilly 1 0.2% Braun Strowman & Nicholas 1 0.2% British Strong Style 1 0.2% Daisuke Sekimoto & Kazusada Higuchi 1 0.2% Dolph Ziggler & Drew McIntyre 1 0.2% Io Sharai 1 0.2% J.A.N. -

2012-13 North Carolina Wrestling Results Dual Meet Record

Frank Abbondanza Riley Allen Christian Barber Jake Barnhart Blake Blair Brian Bokoski Houston Clements Bob Coe Josh Craig Jake Crawford Tanner Eitel Nick Heilmann Troy Heilmann Evan Henderson Robert Henderson Cody Karns Nathan Kraisser Josh Lehner Luke Mario Scott Marmoll Chris Mears Matthew Meyer Joe Moon Jacob Pincus Anderson Pope Ethan Ramos Jake Reinemund Cody Ross John Staudenmayer Mitchel Thomas Alex Utley Joey Ward Matt Williams David Woody C.D. Mock Cary Kolat Dennis Papadatos Trevor Chinn 2013-14 NORTH CAROLINA TAR HEELS 2013-14 NORTH CAROLINA WRESTLING Table Of Contents University Of North Carolina 2013-14 Schedule Page 2 Location: Chapel Hill, N.C. 2013-14 Roster Page 3 Chartered: 1789 2012-13 Results Page 5 Enrollment: 18,503 GENERAL INFORMATION Student-Athlete Profiles Pages 6-14 Chancellor: Carol Folt Head Coach C.D. Mock Page 15 Director of Athletics: Bubba Cunningham Affiliation: NCAA Division I Coaching Staff Page 16 Conference: Atlantic Coast Conference Athletic Administration/Support Staff Page 17 Nickname: Tar Heels The University of North Carolina Pages 18-19 Mascot: Rameses (a ram) Academic Excellence Page 20 Colors: Carolina Blue and White Carolina Leadership Academy Page 21 Athletic Department Web Site: GoHeels.com Chapel Hill Page 22 Athletic Heritage Page 23 Carolina Wrestling Information Wrestling Facilities Page 24 Head Coach: C.D. Mock (North Carolina, 1982) Individual Records Page 25 Record at UNC: 90-87-3 (11th Year) National Honors Page 26 Overall Record: Same (919) 962-5212 ACC Honors Page 27 Office Phone: -

Meet the Innovators Message from the Headmistress

DESIGN THINKING IS INTRODUCED AT SACRED HEART • STEERING OUR STRATEGIC COURSE • ALUMNAE NEWS • AND MORE WINTER 2017, VOL. 11 meet the innovators Message from the Headmistress critically about ways to improve social conditions in ways that address human need—wherever it is found—and to advance humankind. Each day, our educators employ differentiated and inquiry-based instruction to engage the critical thinking of each student. We engage the whole child—mind, heart and body—and accompany each one on a personal journey that will last a lifetime. The outcome of our work at Sacred Heart is the story of each of our alumnae. The lives of Sacred Heart alumnae are our testament. In their lives, we see the efficacy of our spirituality, the value of our goals and the effectiveness of our educational process. Do we see that these girls do, in fact, change the world? Yes, we do! Do we see evidence that their faith moves them to action? Yes, we do! Do we see that INNOVATION is deeply rooted in the educational their critical consciousness moves them to innovate, improve praxis of the Academy of the Sacred Heart as a value, as a and advance society? Yes, we do! Message from the Headmistress ..................1 process and as an outcome. Meet the Innovators .......................................2 Today, St. Madeleine Sophie’s “special sauce” has been Steering Our Strategic Course .....................8 As a value, we spot with ease an appreciation for innovation “tried and true” in over 49 countries of the world, and it has A Big Cup of Business Savvy ...................... 10 in the deep convictions of our foundress St. -

Investigative Case Summary Pertains to the Bombing of the Harry T

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT The following investigative Case Summary pertains to the bombing of the Harry T. Moore1 residence in Mims, Brevard County, Florida, by person or persons unknown who caused the deaths of Harry Tyson Moore and Harriette Vyda Moore2 on December 25, 1951, at approximately 10:20 P. M.. This case has been previously investigated by the Brevard County Sheriff’s Office (BCSO), the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) (Case #44-4036), the Brevard County State Attorney’s Office, and the Florida Department of Law Enforcement (FDLE) under FDLE Case Number EI-91-26-016. Florida Attorney General Charlie Crist reopened this case in December 2004, and assigned the case to the Division of Civil Rights at Fort Lauderdale. The Division of Civil Rights initiated an official investigation of this case on December 21, 2004, under case number LO - 4 -1358. Attorney General Charlie Crist requested assistance from the Florida Department of Law Enforcement. Allison K. Bethel, Esq., Director of Civil Rights for the Attorney General’s (AG) Office, was assigned to direct the general course of the investigation. Frank M. Beisler, Senior Investigator at the Attorney General’s Office (AG) of Civil Rights and Special Agent (SA) C. Dennis Norred, of the Florida Department of Law Enforcement (FDLE) were assigned as primary Investigators. AG staff in Tallahassee was assigned to review information, conduct research, and to make recommendations regarding this investigation. SA Norred opened a criminal investigation under FDLE case number PE-01-0048. To clearly understand the current FDLE and Florida Attorney General’s Office Investigation and its results, it is important to fully understand the depth of the investigations conducted by the previously mentioned agencies. -

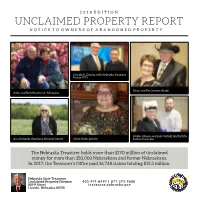

Unclaimed Property Report Notice to Owners of Abandoned Property

2018 EDITION UNCLAIMED PROPERTY REPORT NOTICE TO OWNERS OF ABANDONED PROPERTY Tom Rock, Omaha, with Nebraska Treasurer Photo by KETV Karen and Ken Sawyer, Brady Ardys and Herb Roszhart Jr., Marquette Walter Johnson and Josh Gartrell, North Platte Ann Zacharias Grosshans, Nemaha County Alicia Deats, Lincoln Photo by Tammy Bain The Nebraska Treasurer holds more than $170 million of unclaimed money for more than 350,000 Nebraskans and former Nebraskans. In 2017, the Treasurer’s Office paid 16,748 claims totaling $15.3 million. Nebraska State Treasurer Unclaimed Property Division 402-471-8497 | 877-572-9688 809 P Street treasurer.nebraska.gov Lincoln, Nebraska 68508 Tips from the Nebraska State Treasurer’s Office Filing a Claim If you find your name on these pages, follow any of these easy steps: • Complete the claim form and mail it, with documentation, to the Unclaimed Property Division, 809 P Street, Lincoln, NE 68508. • For amounts under $500, you may file a claim online at treasurer.nebraska.gov. Include documentation. • Call the Unclaimed Property Division at 402-471-8497 or 1-877-572-9688 (toll free). • Stop by the Treasurer’s Office in Suite 2005 of the Capitol or the Unclaimed Property Division at 809 P Street in Lincoln’s Haymarket. Hours are 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday through Friday. Recognizing Unclaimed Property Unclaimed property comes in many shapes and sizes. It could be an uncashed paycheck, an inactive bank account, or a refund. Or it could be dividends, stocks, or the contents of a safe deposit box. Other types are court deposits, utility deposits, insurance payments, lost IRAs, matured CDs, and savings bonds. -

**April Pages.Indd

BISHINIK PRSRT STD P.O. Drawer 1210 U.S. Postage Paid Durant OK 74702 Durant OK RETURN SERVICE REQUESTED Permit #187 THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE CHOCTAW NATION OF OKLAHOMA Serving 168,517 Choctaws Worldwide www.choctawnation.com April 2005 Issue Recovery Center celebrates with ribboncutting The Choctaw Nation has just opened the newly Center were at no cost to any Choctaw who has constructed Recovery Center in Talihina. The a need for the program. The tribe even provides Recovery Program is now able to offer services to transportation assistance to Talihina for Recovery 20 clients at the live-in program. Center clients. Prior to the ribboncutting, Ben Brown, Deputy The new Recovery Center has two nice exercise Director for the State of Oklahoma Substance rooms with equipment, a group room for men Abuse Program, complimented the Choctaw and a second group room for women, each with Recovery Program and facility, saying, “We televisions, personal living quarters shared by have nothing this nice in the State of Oklahoma.” two clients, counseling rooms and state-of-the-art Brown went on to say, “When you come to a kitchen and information technology departments. program like this, you see great things – miracles Darrell Sorrells, the Director of the Recovery happen, lives are restored and families are put Center, said that he and staff had visited other back together.” facilities prior to the final design to get opinions “We think of chemical dependence as a treatable on what worked well and what floor plans illness, and want to provide appropriate care so could be improved. -

Wrestlers Tangle in Pewamo-Westphalia

* 1 HQAG A NO SONS Ca// 224-236 J / BOOK BtNOERS 3 PAPERS-*- Your County News Line Clinton News Day or Night 15 Cents 28 P January 17,1.973 117th Year Vol, 37 ST JOHNS, MICHIGAN 48879 ^9es In St Jdhns, Bath Township '..^ finder' Sewers suffer sndgs an sewage treatment plant here, must now ST JOHNS - Federal budget cuts Averse effect upon St Johns' pro- nationwide community development BATH - Thanks to the Miohigan 03 s er projects, including the $4 million wait 4 to ifyears for federal aid in their outlined by President Nixon have had P ™ ™ project, A number of Attorney General's office the proposed Are you concerned about construction. Bath sewer system is a "neither here getting the straight facts.on a Of the 352 applications for aid in nor there" project question which arises but don't Michigan, renovation of the St Johns An original ruling by the attorney, kngw where to find,the answer? plant is No. 79 on the priority list, with general said Bath could not finance the We'll find the facts for ques funds to install new sewers and a lift project because it amounted to more station farther down at No. 97. than 10% of the unit's state equalized tions submitted by our readers. Current inflationary construction Just drop us a line at FACT valuation. ,, costs will probably make the project Cost of the project would require FINDER, Clinton County News even more expensive by the time aid is, bonds to be issued totalling $3,550,000. St Johns 48879. -

WRESTLING Season Preview the Cortland Wrestling Team 165 - Sophomore Is Coming Off Another Tremendous Jonathan Conroy Had Season

2010-11 Team GuIDE RED DRAGONS WRESTLING Season Preview The Cortland wrestling team 165 - Sophomore is coming off another tremendous Jonathan Conroy had season. The Red Dragons brought a very productive the Empire Conference title back freshman year going home, sent four wrestlers to 23-10. He’s looking Iowa for the NCAA Division III to have a big 2010-11 Championships and came home season for the Red with two All-Americans as well as Dragons. His relentless a Scholar All-American. The team attacking is going to pulled one of the biggest upsets be hard for opponents in conference history when it to handle and fun to overcame heavily favored Ithaca watch. Conroy spent a to win the crown by placing all 10 great summer working wrestlers in the top four of their Sophomore Jonathan Conroy. hard to prepare his respective weight classes. Seniors body for the season, Mike Ciaburri, Martino Sottile and and he is ready. Joe Murphy won their individual Freshmen Pete Delmonaco and Brett mahoney will back up Conroy. DelMonaco Junior Carl Korpi. weight classes, while junior Aljamain brings a great deal of athleticism and eager attitude to learn. Mahoney, who wrestled Sterling received a wild-card berth for former Red Dragon Jason Chase, looks to improve his skills to go along with his after finishing as the runner-up at 133 strength. Also look for senior Eric Eckstrom to return second semester if rehab pounds. The team finished 22nd at the national meet with Sterling finishing fourth and continues on schedule. He’s battled a few setbacks but is determined to finish his Sottile ending his career with an eighth-place finish. -

Substance Abuse Center Attacks Drugs and Alcohol Problems in County

14 PAGES "AUGUST 4, 1976 20 CENTS ST. JOHNS, MICHIGAN 48879 Republican Incumbent Stanley Powell held off challenger Tom Reed in the 88th. Michigan House of Representatives Primary Tuesday night, while Burton Stencel defeated John Fox by a little over 300 votes to Election Results earn the Democratic nomination for the November house'race. Powell received 4152 votes over Reeds 3380. Third Republican on the ballot, Donald Barr received 479 votes.. Stencel received 1BB8 votes and-Fox received 1516. Robert Wood defeated incumbent Powell Reed Barr Stencel Fox Republican Dist. 4 County Commissioner Maurice Gove by 4 votes 1434* i696 183 563 862 Tuesday night. .Wood pulled 272 votes, while Gove received 268. 97 312 17 70 108 Wood, former mayor of St. Johns, will oppose Cecil Smith in the November 119 42 40 34 36 General Election. Smith, unopposed in the Democratic 57 4 1 9 . .38 Primary, received 119 votes. 2445 1326 238 1212 472 4152 3380 Alta Reed, former Clinton County County Commission Commissioner. defeated Dale Emerson, DeWitt Twp. supervisor, in District 4 Tuesday night's election." Reed received 438 votes while Emerson received 386. Bruce Angell SHOPPERS PACKED the Clinton Ave. sidewalks Thursday received 350 votes. Robert Wood 272 Duane Chambe rlain and Friday to take advantage of Sidewalk Sale bargains in Three millage proposals on the St. Johns. Despiie threatening skies early Thursday township ballot went down in defeat in Maurice Gove 268 Vern Fosnight morning, crowds began flocking into St. Johns at 8 a.m. and the light voter turnout. continued through the day and Friday.