DOCTORAL THESIS Title the POLITICAL ROLE AND

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Royal-Dutch-Shell-Fra-Oljemuseets-Årbok-2018.Pdf

Nor sk oljemuseum årbok 201 7 Årboken er Norsk Oljemuseums viktigste, årlige publikasjon. Den tar for seg et bredt spekter av aktuelle tema knyttet til petroleumsnæringen og museets virksomhet. Artiklene er skrevet både av museets egne ansatte og eksterne bidragsytere. Museets årsmelding og regnskap er også å finne i årboken. Norsk Oljemuseumoljemuseum Årbokårbok 20172018 Royal Dutch/Shell av Trude Meland hell har drevet sin verdensomspennende En gryende globalisering Svirksomhet i over 100 år og har bygget opp en Det hele startet i 1833 da Marcus Samuel sr. av verdens mest kjente merkevarer. Royal Dutch/ åpnet en liten forretning i Londons East End Shell som i dag er et multinasjonalt selskap med hvor han handlet med antikviteter, rariteter, hovedkontor i Haag og forretningsadresse i konkylier og dekorative skjell. Skjell og konkylier London, startet som en allianse i 1907. Da slo det var på moten i det viktorianske Storbritannia, og nederlandske Royal Dutch Petroleum Company forretningen var lukrativ.2 og britiske The «Shell» Transport and Trading Company seg sammen. Dette er historien om Den vokste til et blomstrende import- og hvordan Royal Dutch/Shell Group vokste seg eksportfirma, og Samuel organiserte en toveis til å bli et av verdens største foretak, men også handel mellom Storbritannia og det fjerne østen. om de to som startet det – den ene fra Londons Tekstiler og maskiner til å bygge opp en industri østkant, jødisk opprinnelse og ambisiøs. Den gikk fra Storbritannia, og i retur kom ris, kull, andre nederlender, med en hang for detaljer og silke, kobber og porselen. Antall handelspartnere tall. Mennene var Marcus Samuel jr. -

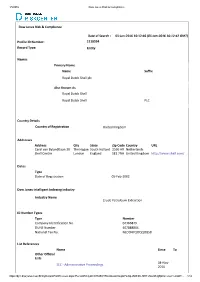

Due Diligence and Stronger Preventative Measures

1/5/2016 Dow Jones Risk & Compliance Dow Jones Risk & Compliance Date of Search : 05‐Jan‐2016 16:12:46 (05‐Jan‐2016 16:12:42 GMT) Profile ID Number: 1118594 Record Type: Entity Names Primary Name Name Suffix Royal Dutch Shell plc Also Known As Royal Dutch Shell Royal Dutch Shell PLC Country Details Country of Registration United Kingdom Addresses Address City State Zip Code Country URL Carel van Bylandtlaan 30 The Hague South Holland 2596 HR Netherlands Shell Centre London England SE1 7NA United Kingdom http://www.shell.com/ Dates Type Date of Registration 05‐Feb‐2002 Dow Jones Intelligent Indexing Industry Industry Name Crude Petroleum Extraction ID Number Types Type Number Company Identification No. 04366849 DUNS Number 407888804 National Tax No. NLOO47QOQQOB58 List References Name Since To Other Official Lists 04‐Nov‐ SEC ‐ Administrative Proceedings 2010 https://djrc.dowjones.com/EntityDetailsPrintPreview.aspx?PersonEntityId=QTMSOYRLnQLwzr0sJpkYw3qLJMB3fUJ9Hf+Z6n/xBJgEpVx+Loo=%20&Pr… 1/12 1/5/2016 Dow Jones Risk & Compliance GAO (US) Report on Exporters of Refined Petroleum Products to Iran Sep‐2010 GAO (US) Report on firms to have Engaged in Commercial Activities in 23‐Mar‐ 03‐Aug‐ Iran’s Energy Sector 2010 2011 New Jersey Report to the Legislature regarding Investments in Iran ‐ 01‐Mar‐ 03‐Mar‐ Prohibited List 2012 2014 Close Associates/Related Entities Name Type Relation Raízen Combustiveis SA Entity Asset A/S Dansk Shell Entity Subsidiary CRI Catalyst Company Belgium NV Entity Subsidiary Equilon Enterprises Limited Liability Entity Subsidiary Company Nederlandse Aardolie Maatschappij BV Entity Subsidiary Pilipinas Shell Petroleum Corporation Entity Subsidiary Shell Australia Limited Entity Subsidiary Shell Bulgaria Single Person Joint Stock Entity Subsidiary Company Shell Canada Limited Entity Subsidiary Shell Compañía Argentina De Petróleo SA Entity Subsidiary Shell E&P Ireland Limited Entity Subsidiary Shell Eastern Petroleum (Private) Limited Entity Subsidiary Shell Energy North America (US) L.P. -

TANZANIA OIL and GAS ALMANAC TANZANIA OIL and GAS ALMANAC Print Edition June 2015

TANZANIA OIL AND GAS ALMANAC TANZANIA TANZANIA OIL AND GAS ALMANAC Print edition June 2015 A Reference Guide published by the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Tanzania and OpenOil Tanzania Oil and Gas Almanac A Reference Guide published by the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Tanzania and OpenOil EDITORIAL Abdallah Katunzi – Chief Editor Marius Siebert – Deputy Editor PUBLISHED BY Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung P.O Box 4472 Mwai Kibaki Road Plot No. 397 Dar es Salaam, Tanzania Telephone: 255-22-2668575/2668786 Email: [email protected] PRINTED BY FGD Tanzania Ltd P.O. Box 40331 Dar es Salaam Disclaimer While all efforts have been made to ensure that the information contained in this book has been obtained from reliable sources, FES (Tanzania) bears no responsibility for oversights or omissions. ©Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, 2015 ISBN: 978-9987-483-36-5 A commercial resale of this publication is strictly prohibited unless the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung gives explicit and written approval beforehand. PREFACE With an estimated gas reserve of more than 55 trillion cubic feet (Tcf), Tanzania readies itself to join the gas economy. Large multinational oil companies are currently exploring natural gas and oil in various parts of Tanzania – both offshore and onshore. Despite these huge discoveries, there is little publicly available information on natural gas on a wide range of issues. Consequently, the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES), Tanzania, with the technical support of OpenOil– a Berlin based organisation – created the Tanzania Oil and Gas Almanac as a living database for publicly available information around the country’s Oil and Gas sector. It has been created to significantly increase the stock of information available in local contexts among extractive stakeholders including civil society organizations, government, journalists and companies. -

Conflict-Sensitive Journalism and the Nigerian Print Media Coverage of Jos Crisis, 2010-2011

CONFLICT-SENSITIVE JOURNALISM AND THE NIGERIAN PRINT MEDIA COVERAGE OF JOS CRISIS, 2010-2011. BY JIDE PETER JIMOH Matric No. 130129 B.SC, M.SC MASS COMMUNICATION (UNILAG), M.A. PEACE AND CONFLICT STUDIES (IBADAN) A thesis in Peace and Conflict Studies submitted to the Institute of African Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of the UNIVERSITY OF IBADAN UNIVERSITY OF IBADAN LIBRARYMarch 2015 ABSTRACT The recent upsurge of crises in parts of Northern Nigeria has generated concerns in literature with specific reference to the role of the media in fuelling crises in the region. Previous studies on the Nigerian print media coverage of the Jos crisis focused on the obsolescent peace journalism perspective, which emphasises the suppression of conflict stories, to the neglect of the UNESCO Conflict-sensitive Journalism (CSJ) principles. These principles stress sensitivity in the use of language, coverage of peace initiatives, gender and other sensitivities, and the use of conflict analysis tools in reportage. This study, therefore, examined the extent to which the Nigerian print media conformed to these principles in the coverage of the Jos violent crisis between 2010 and 2011. The study adopted the descriptive research design and was guided by the theories of social responsibility, framing and hegemony. Content analysis of newspapers was combined with In-depth Interviews (IDIs) with 10 Jos-based journalists who covered the crisis. Four newspapers – The Guardian, The Punch, Daily Trust and National Standard were purposively selected over a period of two years (2010-2011) of the crisis. A content analysis coding schedule was developed to gather data from The Guardian (145 editions with 46 stories), The Punch (148 editions with 85 stories), Daily Trust (148 editions with 223 stories) and National Standard (132 editions with 187 stories) totalling 573 editions which yielded 541 stories for the analysis. -

Royal Dutch Shell - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Royal Dutch Shell from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

10/5/12 Royal Dutch Shell - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Royal Dutch Shell From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Royal Dutch Shell plc Royal Dutch Shell plc (LSE: RDSA Type Public limited company Traded as LSE: RDSA (http://www.londonstockexchange.com/exchange/prices- and-news/stocks/prices-search/stock-prices-search.html? nameCode=RDSA) , RDSB (http://www.londonstockexchange.com/exchange/prices- and-news/stocks/prices-search/stock-prices-search.html? nameCode=RDSB) Euronext: RDSA (http://www.euronext.com/quicksearch/resultquicksearch- 2986-EN.html? matchpattern=RDSA&entryType=symbol) , RDSB (http://www.euronext.com/quicksearch/resultquicksearch- 2986-EN.html? matchpattern=RDSB&entryType=symbol) NYSE: RDS.A (http://www.nyse.com/about/listed/quickquote.html? ticker=rds.a) , RDS.B (http://www.nyse.com/about/listed/quickquote.html? ticker=rds.b) Industry Oil and gas Founded 1900 Headquarters The Hague, Netherlands (Headquarters) Shell Centre, London, United Kingdom (Registered office) Area served Worldwide Key people Peter Voser (CEO) en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Dutch_Shell 1/16 10/5/12 Royal Dutch Shell - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (CEO) Jorma Ollila (Chairman) Products Petroleum, natural gas, and other petrochemicals Revenue US$ 470.171 billion (2011)[1] Operating US$ 55.660 billion (2011)[1] income Profit US$ 31.185 billion (2011)[1] Total assets US$ 345.257 billion (2011)[1] Total equity US$ 169.517 billion (2011)[1] Employees 90,000 (2011)[1] Subsidiaries List Website Shell.com (http://www.shell.com) (http://www.londonstockexchange.com/exchange/prices-and-news/stocks/prices-search/stock-prices- search.html?nameCode=RDSA) , RDSB (http://www.londonstockexchange.com/exchange/prices-and- news/stocks/prices-search/stock-prices-search.html?nameCode=RDSB) ), commonly known as Shell, is a Dutch–British multinational oil and gas company headquartered in The Hague, Netherlands and with its registered office in London, United Kingdom.[2] It is the world's second largest company by 2011 revenues and one of the six oil and gas "supermajors". -

The Press and Politics in Nigeria: a Case Study of Developmental Journalism, 6 B.C

UIC School of Law UIC Law Open Access Repository UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship 1-1-1986 The Press and Politics in Nigeria: A Case Study of Developmental Journalism, 6 B.C. Third World L.J. 85 (1986) Michael P. Seng John Marshall Law School Gary T. Hunt Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael P. Seng & Gary T. Hunt, The Press and Politics in Nigeria: A Case Study of Developmental Journalism, 6 B. C. Third World L. J. 85 (1986). https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs/301 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PRESS AND POLITICS IN NIGERIA: A CASE STUDY OF DEVELOPMENTAL JOURNALISM MICHAEL P. SENG* GARY T. HUNT** I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................... 85 II. PREss FREEDOM IN NIGERIA 1850-1983 .................................. 86 A. The Colonial Period: 1850-1959 ....................................... 86 B. The First Republic: 1960-1965 ........................................ 87 C. Military Rule: 1966-1979 ............................................. 89 D. The Second Republic: 1979-1983 ...................................... 90 III. THE THEORETICAL FOUNDATION FOR NIGERIAN PRESS FREEDOM: 1850- 1983 ..................................................................... 92 IV. TOWARD A NEw RoLE FOR THE PRESS IN NIGERIA? ....................... 94 V. THE THIRD WORLD CRITIQUE OF THE WESTERN VIEW OF THE ROLE OF THE PRESS .................................................................... 98 VI. DEVELOPMENTAL JOURNALISM: AN ALTERNATIVE TO THE WESTERN VIEW OF THE ROLE OF THE PRESS .............................................. -

The Press and Politics in Nigeria: a Case Study of Developmental Journalism, 6 B.C

Boston College Third World Law Journal Volume 6 | Issue 2 Article 1 6-1-1986 The rP ess and Politics in Nigeria: A Case Study of Developmental Journalism Michael P. Seng Gary T. Hunt Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/twlj Part of the African Studies Commons, Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Politics Commons Recommended Citation Michael P. Seng and Gary T. Hunt, The Press and Politics in Nigeria: A Case Study of Developmental Journalism, 6 B.C. Third World L.J. 85 (1986), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/twlj/vol6/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Third World Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PRESS AND POLITICS IN NIGERIA: A CASE STUDY OF DEVELOPMENTAL JOURNALISM MICHAEL P. SENG* GARY T. HUNT** I. INTRODUCTION........................................................... 85 II. PRESS FREEDOM IN NIGERIA 1850-1983 .................................. 86 A. The Colonial Period: 1850-1959....................................... 86 B. The First Republic: 1960-1965 . 87 C. Military Rule: 1966-1979............................................. 89 D. The Second Republic: 1979-1983...................................... 90 III. THE THEORETICAL FOUNDATION FOR NIGERIAN PRESS FREEDOM: 1850- 1983..................................................................... 92 IV. TOWARD A NEW ROLE FOR THE PRESS IN NIGERIA?...................... 94 V. THE THIRD WORLD CRITIQUE OF THE WESTERN VIEW OF THE ROLE OF THE PRESS.................................................................... 98 VI. DEVELOPMENTAL JOURNALISM: AN ALTERNATIVE TO THE WESTERN VIEW OF THE ROLE OF THE PRESS. -

Rapportering Og Revisjon Av Olje- Og Gassreserver

NORGES HANDELSHØYSKOLE Bergen, 18.06.2007 Rapportering og revisjon av olje- og gassreserver med utgangspunkt i Shell-skandalen 2004. Olav Søvik Olsen Veileder: Professor Aasmund Eilifsen Utredning i fordypningsområdet: Økonomisk styring NORGES HANDELSHØYSKOLE Denne utredningen er gjennomført som et ledd i masterstudiet i økonomisk-administrative fag ved Norges Handelshøyskole og godkjent som sådan. Godkjenningen innebærer ikke at høyskolen innestår for de metoder som er anvendt, de resultater som er fremkommet eller de konklusjoner som er trukket i arbeidet. Masteroppgave Rapportering og revisjon av olje- og gassreserver Sammendrag Denne utredningen starter med å presentere oljeselskapet Royal Dutch Shell og deretter tar den for seg Shell sin skandale i 2004 vedrørende rapportering av olje- og gassreserver. Det fokuseres her på hvordan toppledelsen til Shell håndterte situasjonen, samt hvilke rapporteringsregelverk som var gjeldende. Etter dette tar utredningen for seg hvordan rapporteringen av olje- og gassreserver foregår og hvilke rammeverk for rapportering som er det beste i dag. Det kommer frem av denne innsikten at rammeverket til Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE) er et av de mest brukte og anerkjente i oljebransjen, og det gis eksempler på hvordan estimering av olje- og gassreserver foregår etter dette rammeverket. Til slutt i oppgaven presenteres det ulike moment som er viktige for en attestasjon/revisjon av et oljeselskaps olje- og gassreserver. Ved utarbeidelsen av disse momentene blir hovedsakelig ulike revisjonsstandarder, -

The Politics of News Reportage And

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF NEWS REPORTAGE AND PRESENTATION OF NEWS IN NIGERIA: A STUDY OF TELEVISION NEWS BY IGOMU ONOJA B.Sc, M.Sc (Jos). (PGSS/UJ/12674/00) A Thesis in the DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY, Faculty of Social Sciences, Submitted to the School of Postgraduate Studies, UNIVERSITY OF JOS, JOS, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D) of the UNIVERSITY OF JOS. August 2005 ii DECLARATION I, hereby declare that this work is the product of my own research efforts, undertaken under the supervision of Prof. Ogoh Alubo, and has not been presented elsewhere for an award of a degree or certificate. All sources have been duly distinguished and appropriately acknowledged IGOMU ONOJA PGSS/UJ/12674/00 iii CERTIFICATION iv DEDICATION To my wife, Ada, for all her patience while I was on the road most of the time. v ACKNOWLEDEGEMENTS I am most grateful to Professor Ogoh Alubo who ensured that this research work made progress. He almost made it a personal challenge ensuring that all necessary references and corrections were made. His wife also made sure that I was at home any time I visited Jos. Their love and concern for this work has been most commendable. My brother, and friend, Dr. Alam’ Efihraim Idyorough of the Sociology Department gave all necessary advice to enable me reach this stage of the research. He helped to provide reference materials most times, read through the script, and offered suggestions. The academic staff of Sociology Department and the entire members of the Faculty of Social Sciences assisted in many ways when I made presentations. -

Investment Policy Review of Nigeria

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT INVESTMENT POLICY REVIEW NIGERIA UNITED NATIONS United Nations Conference on Trade and Development Investment Policy Review Nigeria UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 2009 I Investment Policy Review of Nigeria NOTE UNCTAD serves as the focal point within the United Nations Secretariat for all matters related to foreign direct investment. This function was formerly carried out by the United Nations Centre on Transnational Corporations (1975-1992). UNCTAD’s work is carried out through intergovernmental deliberations, research and analysis, technical assistance activities, seminars, workshops and conferences. The term “country” as used in this study also refers, as appropriate, to territories or areas; the designations employed and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. In addition, the designations of country groups are intended solely for statistical or analytical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgement about the stage of development reached by a particular country or area in the development process. The following symbols have been used in the tables: Two dots (..) indicate that date are not available or not separately reported. Rows in tables have been omitted in those cases where no data are available for any of the elements in the row. A dash (-) indicates that the item is equal to zero or its value is negligible. A blank in a table indicates that the item is not applicable. -

Nigeria's Cobweb of Corruption and the Path To

IJAH, Vol.3 (3) July, 2014 AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ARTS AND HUMANITIES (IJAH) Bahir Dar, Ethiopia Vol. 3 (3), S/No 11, July, 2014: 102-127 ISSN: 2225-8590 (Print) ISSN 2227-5452 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ijah.v3i3.9 NIGERIA’S COBWEB OF CORRUPTION AND THE PATH TO UNDERDEVELOPMENT ALLIYU, Nurudeen, Ph.D., Department of Sociology Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago Iwoye, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] +2348035550187 KALEJAIYE, Peter O. Department of Sociology Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago Iwoye, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] Phone: +2348052334309 & OGUNOLA, Abiodun A. Department of Psychology Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago Iwoye, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] Phone: +2347032329181 Copyright © IAARR 2014: www.afrrevjo.net/ijah 102 Indexed and Listed in AJOL, ARRONET IJAH, Vol.3 (3) July, 2014 Abstract Corruption in Nigeria has grown slowly from the time of pre-independence and it has surely taken over Nigerians’ public and private spaces in the last five decades with compelling evidences to show first among the legislative, the executives and recently the judicial arms of government as well as the unexpected quarters in the private sectors such as the Stock Exchange. This paper highlights several factors and institutions in Nigerian society that have sustained and entrenched corrupt practices by government officials and high profile private sectors participants. The institutions identified here are regarded as eaters of corruption proceeds around which a cobweb of corruption has been weaved by the corrupt public/private individuals to create a network under the control of the grandfather- spider of corruption (The federal government); the father- spiders (the state government) and the children- spider ( the local governments spread across the Nigerian society). -

Africana Libraries Newsletter Issn 0148-7868

AFRICANA LIBRARIES NEWSLETTER ISSN 0148-7868 Africana Libraries Newsletter (ALN) is published quarterly by the Michigan State Univer sity Libraries and African Studies Center(East Lansing, MI 48824). Those copying contents are asked to cite ALN as their source. ALN is produced to support the work of the Archives- TABLE OF CONTENTS Libraries Committee (ALC) of the African Studies Association. It carries the meeting min utes of ALC, CAMP (Cooperative Africana Microform Project) and other relevant groups. It also reports other items of interest to Africana librarians and those concerned about Editor’s Comments information resources in or about Africa. Acronyms Editor: Joseph J. Lauer, Africana Library, MSU, East Lansing, MI 48824-1048. ALC/CAMP NEWS.......................................................2 Tel.: 517-355-2366; E-mail: [email protected]; Fax: 517-336-1445. Calendar of Future Meetings Deadline for no. 68: October 1, 1991. ALC Business Meeting (April 18) Minutes Bibliography Sub. Meeting (April 18) Minutes Cataloging Subcommittee Meeting (April 19) Minutes EDITOR’S COMMENTS African Language Codes Working Group Discussion ALC Executive Board, 1990/91 This is the first issue of ALN from Michigan State. It continues the work of CAMP Business Meeting (April 19) Minutes earlier editors: James Armstrong and Gretchen Walsh at Boston (1975-1983), Serials Task Force Meeting (April 20) Yvette Scheven at Illinois (1983-1986), and Nancy Schmidt at Indiana (1986- OTHER NEWS .............................................................9 1991). ALC and CAMP minutes and notices will continue to receive priority. News from Other Associations There will also be reports on other meetings, bibliographies in progress, selected American Library Association new publications and vendor activités, major new acquisitions and serial Middle East Librarians Association cancellations, job vacancies, etc.