War Through the Eyes of the Toy Soldier: a Material Study of the Legacy and Impact of Conflict 1880 - 1945

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TOY SOLDIER VICTORY SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 27TH, 2021 and SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 28TH, 2021 Auction 61 TOY SOLDIER VICTORY

TOY SOLDIER VICTORY SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 27TH, 2021 AND SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 28TH, 2021 Auction 61 TOY SOLDIER VICTORY Old Toy Soldier Auctions U.S.A. Auction #61 P.O. Box 13323 • Pittsburgh, PA 15243 Saturday, February 27th, 2021 - 10am Est ~ Lots 1001-1574 412-343-8733 Sunday, February 28th, 2021 - 10am Est ~ Lots 2001-2605 Fax 412-344-5273 Buyers Premium 23% Discounted to 20% for Check or Cash [email protected] www.oldtoysoldierauctions.comon light backgrounds on dark backgrounds standard standard Website: Absentee & Phone Bidding Deadline: no gradients facebook.com/oldtoysoldierno gradients oldtoysoldierauctions.com Friday, January 15th, 2021 at 7PM Eastern Time watermark @oldtoysoldierwatermark oldtoysoldier Preview Auction at: stacked logo (for sharing only) stacked logo (for sharing only) Day 1 - Lots 1001-1574 Ray and Bre Live Liveauctioneers.com or oldtoysoldierauctions.com Cataloged and shipped by 3 weeks prior to sale Dan Jones Hartford, CT Bid Live Online the Day of Sale at: Liveauctioneers.com Day 1 - Lots 2001-2605 Cataloged and shipped by Mail Bids & Payments To: Keith and Paula Maladra Old Toy Soldier Auctions Batavia, IL P.O. Box 13323, Pittsburgh, PA 15243 Prices Realized: Call Bids To: Liveauctioneers.com or Ray Haradin 412-343-8733 oldtoysoldierauctions.com after the sale closes Fax Bids To: 412-344-5273 Consign with us today! Email Bids To: [email protected] Ray Haradin 412-343-8733 [email protected] 1 OLD TOY SOLDIER SQUAD SPECIALIST SQUAD Ray Haradin Scott Morlan John Gilliatt Pittsburgh, PA Friday Harbor, WA Courtenay Knights -

Showcase LION’S LAST STAND Leonidas, Which Is Greek for “Lion’S Son” Or “Lion-Like,” Was Born Around 540 B.C., the Son of T Y King Anaxandrides II

could be of a delicate nature, the Persian threat to their freedom led many Greeks to unite SC together in an alliance. TH AL While the Persians’ superior numbers /6 E eventually overran the Greeks, the defenders’ 1 sacrifice has never been forgotten. Monuments to both the Spartans and the Thespians can be found at Thermopylae today. The last stand at Thermopylae has also captured the popular imagination thanks to books like Steven Pressfield’s fictional “Gates of Fire.” Movies include 1962’s “The 300 Spartans,” starring Richard Egan as Leonidas; and 2006’s “300,” with Gerard Butler portraying the Greek commander. SHOWCASE LION’S LAST STAND Leonidas, which is Greek for “Lion’s son” or “Lion-like,” was born around 540 B.C., the son of T Y King Anaxandrides II. At this time Sparta had two H kings who shared in ruling the state. One leader would be a descendant of the Agiad dynasty, as E M was Leonidas, while the other would be a S R descendant of Eurypon in this twin monarchy. IXTH A Leonidas was married to Gorgo, the daughter of his half-brother King Cleomenes I. At some point between 490 and 488 B.C., Leonidas became King after his half-brother went mad and committed suicide. Scott J. Dummitt and Bill Thomas Leonidas faced a difficult decision as the Persian invasion of Greece developed. Spartan cover the latest action figure- law forbade him from leading the army out of the kingdom during a religious festival being held at the time. However, it would be unthinkable to not related items. -

Dp Guide Lite Us

Dreamcast USA Digital Press GB I GB I GB I 102 Dalmatians: Puppies to the Re R1 Dinosaur (Disney's)/Ubi Soft R4 Kao The Kangaroo/Titus R4 18 Wheeler: American Pro Trucker R1 Donald Duck Goin' Quackers (Disn R2 King of Fighters Dream Match, The R3 4 Wheel Thunder/Midway R2 Draconus: Cult of the Wyrm/Crave R2 King of Fighters Evolution, The/Ag R3 4x4 Evolution/GOD R2 Dragon Riders: Chronicles of Pern/ R4 KISS Psycho Circus: The Nightmar R1 AeroWings/Crave R4 Dreamcast Generator Vol. 01/Sega R0 Last Blade 2, The: Heart of the Sa R3 AeroWings 2: Airstrike/Crave R4 Dreamcast Generator Vol. 02/Sega R0 Looney Toons Space Race/Infogra R2 Air Force Delta/Konami R2 Ducati World Racing Challenge/Acc R4 MagForce Racing/Crave R2 Alien Front Online/Sega R2 Dynamite Cop/Sega R1 Magical Racing Tour (Walt Disney R2 Alone In The Dark: The New Night R2 Ecco the Dolphin: Defender of the R2 Maken X/Sega R1 Armada/Metro3D R2 ECW Anarchy Rulez!/Acclaim R2 Mars Matrix/Capcom R3 Army Men: Sarge's Heroes/Midway R2 ECW Hardcore Revolution/Acclaim R1 Marvel vs. Capcom/Capcom R2 Atari Anniversary Edition/Infogram R2 Elemental Gimmick Gear/Vatical R1 Marvel vs. Capcom 2: New Age Of R2 Bang! Gunship Elite/RedStorm R3 ESPN International Track and Field R3 Mat Hoffman's Pro BMX/Activision R4 Bangai-o/Crave R4 ESPN NBA 2 Night/Konami R2 Max Steel/Mattel Interact R2 bleemcast! Gran Turismo 2/bleem R3 Evil Dead: Hail to the King/T*HQ R3 Maximum Pool (Sierra Sports)/Sier R2 bleemcast! Metal Gear Solid/bleem R2 Evolution 2: Far -

Toy Story: How Pixar Reinvented the Animated Feature

Summers, Sam. " From Shelf to Screen: Toys as a Site of Intertextuality." Toy Story: How Pixar Reinvented the Animated Feature. By Susan Smith, Noel Brown and Sam Summers. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. 127–140. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 1 Oct. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501324949.ch-008>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 1 October 2021, 01:34 UTC. Copyright © Susan Smith, Sam Summers and Noel Brown 2018. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 1 27 Chapter 8 F ROM SHELF TO SCREEN: TOYS AS A SITE OF INTERTEXTUALITY Sam Summers Intertextuality, as defi ned by Julia Kristeva, is ‘the passage from one sign sys- tem to another’,1 or rather, the inherent interconnectedness of all signs and, by extension, all texts. ‘Any text’, she claims, ‘is constructed as a mosaic of quota- tions; any text is the absorption and transformation of another’. 2 It is true that no text is created or received in a vacuum, and all authors and readers bring with them their past experiences, whether textual or otherwise. A text such as Toy Story (John Lasseter, 1995), though, explicitly activates and draws upon these links more than most. Noel Brown’s chapter in this book highlights some of the cultural references found in the fi lm’s script, and the ways in which these intertextual gags contribute towards its dual address by reaching out to mul- tiple demographics. Here, though, I focus on the connections established by the toys themselves, and in particular the meanings they can create for a child audience. -

An Analysis of Torture Scenes in Three Pixar Films Heidi Tilney Kramer University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School January 2013 Monsters Under the Bed: An Analysis of Torture Scenes in Three Pixar Films Heidi Tilney Kramer University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Kramer, Heidi Tilney, "Monsters Under the Bed: An Analysis of Torture Scenes in Three Pixar Films" (2013). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4525 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Monsters Under the Bed: An Analysis of Torture Scenes in Three Pixar Films by Heidi Tilney Kramer A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Women’s and Gender Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Elizabeth Bell, Ph.D. David Payne, Ph. D. Kim Golombisky, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 26, 2013 Keywords: children, animation, violence, nationalism, militarism Copyright © 2013, Heidi Tilney Kramer TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ................................................................................................................................ii Chapter One: Monsters Under -

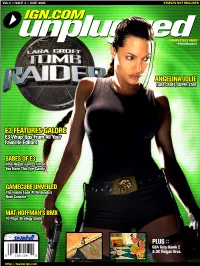

Ign.Com IGN.COM Unplugged 002 Vol

VOL.1 :: ISSUE 3 :: JUNE 2001 STAPLES NOT INCLUDED IGN.COM unpluggedCOMPLETELY FREE* *FOR IGNinsiders ANGELINA JOLIE LARA CROFT, SUPER STAR EE33 FFEEAATTUURREESS GGAALLOORREE EE33 WWrraapp--UUppss FFrroomm AAllll YYoouurr FFaavvoorriittee EEddiittoorrss BBAABBEESS OOFF EE33 WWhhoo NNeeeeddss GGaammeess WWhheenn YYoouu HHaavvee TThhiiss EEyyee--CCaannddyy GAMECUBE UNVEILED The Inside Look At Nintendo''s New Console MMAATT HHOOFFFFMMAANN''SS BBMMXX 1100 PPaaggee SSttrraatteeggyy GGuuiiddee snowball PLUS :: GBA Tony Hawk 2 & DC Floigan Bros. http://insider.ign.com IGN.COM unplugged http://insider.ign.com 002 vol. 1 :: issue 3 :: june 2001 unplugged :: contents Dear IGN Reader -- s3 pecial What you see before you is a E ROUND-UP sample issue of our monthly PDF ISSUE magazine, IGN Unplugged. We have limited this teaser to just a mail call :: 003 few pages, randomly selected from the June issue of the full 90 news :: 006 page-magazine. You can download releases :: 008 IGN Unplugged to your hard drive and read it on your computer or easily print it out and take it with dreamcast :: 022 you to pass some time on long Feature: E3 Wrap-Up trips (or the can). Previews gamecube :: 026 Subscribers to IGN's Insider service get a new issue of Feature: E3 Wrap-Up Unplugged every month -- but Feature: GameCube Unveiled that's just a fraction of the great Previews content and services you receive playstation 2 :: 035 for supporting our network. Feature: E3 Wrap-UP IGNinsider is updated daily with Feature: Sony's Online Plans cross-platform discussions, Previews detailed features and high-quality handhelds :: 043 downloads. Some of the stories Feature: E3 Wrap-Up are offered to non-subscribers for Previews free at a later date, others remain xbox :: 047 on IGNinsider forever. -

Toy Soldier Collector Magazine

68 PAGES OF TOY SOLDIERS | IN-DEPTH FEATURES | COMPETITION | SHOW DATES Dec/Jan 2008 | Issue 19 | £4.50 TOY SOLDIER www.toysoldiercollector.com COLLECTOR WE’RE AS SERIOUS ABOUT COLLECTING AS YOU ARE Heritage Miniatures WIN Zulu War sets by Making the Streets of New WWI Cavalry Frontline Figures Old Hong Kong GODS OF OVER 85 WAR new FIGURES/SETS Russian Vityaz REVIEWED Roman elephant EVERY ISSUE: NEW METAL | PLASTICS | CASTINGS PLUS: NEWS | HISTORY | READERS LETTERS Please pre-order this piece from your local retailer to avoid disappointment 17869 – A complete British Royal Field Artillery Limber with 18 Available Pound Gun that includes Gun, Limber, Six Horses, Two February 2008 Outriders and Two Limber Riders. This 11 Piece Set is strictly LIMITED TO 450 SETS WORLDWIDE. These figures are 54mm (2.25") Tall Matte Connoisseur Finish For more information on the new World War I releases and to find Metal Military Miniatures. Use this stunning piece with the a retailer near you please contact W. Britain at: extensive W. Britain World War I collection that includes British From the UK, Ireland and Continental Europe From the United States, Canada, Central and South America infantry, highlanders and cavalry, as well as French infantry and W. Britain Ltd. at: First Gear / W. Britain Consumer Services Department at: Wireless Hill Industrial Estate • South Luffenham P.O. Box 52 • Peosta, Iowa 52068-0052 German infantry and cavalry. Oakham • Rutland • LE15 8NF • United Kingdom Toll Free: (888) 771-5576 or (563) 582-2071 Tel: (0) 1780 721723 • Fax: (0) 1780 729513 Fax: (563) 582-2415 Email: [email protected] • Website: www.wbritain.com Email: [email protected] • Website: www.wbritain.com WBA5007 ©2007 FIRST GEAR, INC. -

Soldiers Cheats

Soldiers cheats click here to download Small Soldiers Cheats - PlayStation Cheats: This page contains a list of cheats, codes, Easter eggs, tips, and other secrets for Small Soldiers for. Get all the inside info, cheats, hacks, codes, walkthroughs for Toy Soldiers on GameSpot. Level Level Password Gorgon X, X, Triangle, Square, Square, X, Circle, X Dimensional Temple Square, X, Triangle, Square, Square, Square, Circle, X Floating. Alright first of all when you're playing a game push the P key to bring up the cheat activator. There a two codes, POPCICLE STICKS and BIG JUICY GUN. Invincibility. Enter Circle, Circle, Triangle, Triangle, Circle, X, Square, X as a password. All weapons. Enter Triangle, Triangle, Circle, Circle, Circle, X, Square, . The best place to get cheats, codes, cheat codes, walkthrough, guide, FAQ, unlockables, achievements, and secrets for Toy Soldiers for Xbox For Toy Soldiers on the Xbox , GameRankings has 22 cheat codes and secrets. Get the latest Toy Soldiers cheats, codes, unlockables, hints, Easter eggs, glitches, tips, tricks, hacks, downloads, achievements, guides, FAQs, walkthroughs. The following cheats, codes, and secrets are available for the Army Men: RTS strategy video game on the Nintendo Gamecube video game. For years, Signal Studios has been taking to the front lines of toy battles with its Toy Soldiers game series. Action Replay codes. 00C Infinite lives - Player 1 (keeps showing 9); 00C Infinite lives - Player 2 (keeps showing 9); 00C10E Invincibility. Small Soldiers cheats, codes, walkthroughs, guides, FAQs and more for PlayStation. Do you Play Soldiers Inc.? Join www.doorway.ru our members share free bonus, tips, guides & valid cheats or tricks if found working. -

Sega Dreamcast European PAL Checklist

Console Passion Retro Games The Sega Dreamcast European PAL Checklist www.consolepassion.co.uk □ 102 Dalmatians □ Jeremy McGrath Supercross 2000 □ Slave Zero □ 18 Wheeler American Pro Tucker □ Jet Set Radio □ Sno Cross: Championship Racing □ 4 Wheel Thunder □ Jimmy White 2: Cueball □ Snow Surfers □ 90 Minutes □ Jo Jo Bizarre Adventure □ Soldier of Fortune □ Aero Wings □ Kao the Kangaroo □ Sonic Adventure □ Aero Wings 2: Air Strike □ Kiss Psycho Circus □ Sonic Adventure 2 □ Alone in the Dark: TNN □ Le Mans 24 Hours □ Sonic Shuffle □ Aqua GT □ Legacy of Kain: Soul Reaver □ Soul Calibur □ Army Men: Sarge’s Heroes □ Looney Tunes: Space Race □ Soul Fighter □ Bangai-O □ Magforce Racing □ South Park Rally □ Blue Stinger □ Maken X □ South Park: Chef’s Luv Shack □ Buggy Heat □ Marvel vs Capcom □ Space Channel 5 □ Bust A Move 4 □ Marvel vs Capcom 2 □ Spawn: In the Demon Hand □ Buzz Lightyear of Star Command □ MDK 2 □ Spec Ops 2: Omega Squad □ Caesars Palace 2000 □ Metropolis Street Racer □ Speed Devils □ Cannon Spike □ Midway’s Greatest Hits Volume 1 □ Speed Devils Online □ Capcom vs SNK □ Millennium Soldier: Expendable □ Spiderman □ Carrier □ MoHo □ Spirit of Speed 1937 □ Championship Surfer □ Monaco GP Racing Simulation 2 □ Star Wars: Demolition □ Charge ‘N’ Blast □ Monaco GP Racing Simulation 2 Online □ Star Wars: Episode 1 Racer □ Chicken Run □ Mortal Kombat Gold □ Star Wars: Jedi Power Battles □ Chu Chu Rocket! □ Mr Driller □ Starlancer □ Coaster Works □ MTV Sports Skateboarding □ Street Fighter 3: 3rd Strike □ Confidential Mission □ NBA 2K -

Yesterday's Toy Soldiers

The Toy Soldier Shop of Washington, D.C.’s new advertisement touting the shop’s offerings the genre of toy soldier I first saw and played with more than seventy-five years ago. Fortunately, for the adult, The German Heyde made West Point cadets to accompany the F.A.O. West Point barracks Toy Soldier Shop allows you to recapture that burst of won- derment you experienced in your childhood when you opened your first box of metal Yesterday’s soldiers. These are figures, however, for a collector, not toys for today’s children to play with which come from toy soldiers the other side of the world. If discovery of the Heyde Retired Brigadier General Raymond E. Bell takes cadets on the shelf in parade a trip to a very special US toy soldier shop… formation was a great find, a look at several old sets in prime condition being t a recent large auc- prepared for viewing and tion, an F.A.O. Schwarz sale revealed an interesting A special wood model and vastly different array of of a barracks representing figures for sale. Neil specially one that might be found at the favors the pre-World War II United States Military Acad- Heyde figures along with the emy at West Point, New York compatible sized German went on the block. The model Krause and Haffner soldiers struck a special note with of which he offers a wide me as at the age of five years selection of such figures for old my mother purchased you to take home with you. -

Week 2: Game Theory // History & Origins // Industry Stats

NMED 3300(A) // Theory and Aesthetics of Digital Games Friday Genre Discussions / Play Sessions Schedule, Spring 2016 Mondays and Wednesdays will consist of lectures. Fridays will be broken into two sessions. The first will take place in W866 where we will discuss particular genres and look at select examples. The second session will take place in W560 and will consist of hands-on gameplay (1 hour) of the games covered earlier in class. Some Rules for W560 Usage: 1. Please be considerate of others in the lab and those working in adjacent offices/classrooms by keeping noise to a minimum, 2. Please note that food and drink are not allowed in W560, except water if it is contained in a non-spillable container (with a screw-top or sealable cap) 3. Only students with official access are allowed in these labs (you cannot bring friends into the lab, sorry), 4. Please be gentle with equipment, consoles, and peripherals as a lot of the equipment is David’s personal property and much of the equipment is old and getting more difficult (if not impossible) to replace. 5. Finally, do not leave discs in consoles and make sure consoles and televisions are turned off when you are finished and that the area where you were working is clean and tidy. Notes on Gameplay Sessions in W560: Please keep the volume of the monitors and verbalizations to a minimum. Have a look at each of the games listed for that week’s gameplay sessions by consulting reviews/criticism, gameplay video, screenshots. As many games are released on multiple platforms and are often emulated, make sure you are viewing information for the correct version (platform, year). -

Edwardian Splendour

Edwardian Splendour A KRIEGSPIEL FOR TOY SOLDIERS By Arofan Gregory. Copyright © 2006. All rights reserved. For my son, Calum, in the hope that he may someday play this game with me, and to his mother, Joanna, who will no doubt think the whole thing is silly but will let us do it anyway. If you have questions or comments, please contact Arofan Gregory by e-mail at [email protected]. 2 Introduction: Traditional toy soldiers possess a charm that is not duplicated by their smaller 15mm and 25mm brethren. No matter how many wargaming figures one collects, there is an attraction to the larger figures which remains un-sated. Whether you are talking about 42mm semi-rounds or the larger 54mm full-round figures, they possess an evocative quality that smaller figures lack. It is something which says “toy soldier” and reminds us that, no matter how complex our rules are, in the final analysis, miniature wargaming is still on some level “playing with toy soldiers.” At the same time, a miniatures wargamer needs a reason to collect armies – there must be a game to play, and it should simulate something historical, at some level, to capture the imagination. I am a miniatures wargamer first, and a collector of toy soldiers second: these rules represent my solution to the problem presented by this fusion of interests. This is a simple game for use with full-round and semi-round toy soldiers from 40mm to 54mm in height. Created in the spirit of H.G. Wells’ Little Wars, H.G. Dowdall’s Shambattle, and the kriegspiel games of that era, it represents combat during the late 19th/early 20th centuries, the periods for which traditional toy soldiers are often made.