A Look at How the Australian Home Front Understood the Gallipoli Campaign

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Listening-Post-June-2015.Pdf

Listening POSTJUNE 2015 Vol 38 - No 2 ANZAC 2015 The Official Journal of The Returned & Services League of Australia WA Branch Incorporated 2 The Listening Post JUNE 2015 contents 3 Records broken on ANZAC Day 4 VP Day – bitter sweet memories contact: 5 President’s Pen Editorial and Advertising 6 Your Letters Information Acting Editor: Amy Hunt 9287 3700 7 Bits & Pieces Email: [email protected] 8 The Horrors of the Somme Media & Marketing Manager: John Arthur 0411 554 480 11 Fun Run hides burning Email: [email protected] ambition Graphic Design: Type Express 12 Couple recall WWII Printer: Rural Press 14 Domingos de Oliviera Contact Details 16 Memorable Sunset The Returned & Services League Cover: of Australia - WA Branch Incorporated Services Flags of New Zealand and Australia were ANZAC House, 28 St Georges Tce carried together through Perth on ANZAC PERTH WA 6000 17-47 ANZAC Day Services Day to mark the Centenary of the combined PO Box 3023, EAST PERTH WA 6892 around the State forces landing at Gallipoli. Email: [email protected] 48 New Members Website: www.rslwahq.org.au The march by more than 7,000 veterans, Facebook: www.facebook.com/rslwahq ADF personnel, bands and descendants 49 Christmas in July drew tens of thousands of people onto Perth Telephone: 9287 3799 streets to honour our fallen. 50-52 Sub-Branch News Fax: 9287 3732 WA Country Callers: 1800 259 799 In this edition, we devote nearly 30 pages 53 Notices to ANZAC Day services held throughout Contact Directory the State. The RSL hosted services at 54 Crossword and Suduko more than 100 locations and in many towns CEO / State Secretary: these services included events leading up to 55 Last Post and Solutions Philip Orchard AFNI RAN (Rtd) ANZAC Day and involved school children. -

Samai King Gifted and Talented Online Anzac Day: Why the Other Eight Months Deserve the Same Recognition As the Landing

THE Simpson PRIZE A COMPETITION FOR YEAR 9 AND 10 STUDENTS 2016 Winner Western Australia Samai King Gifted and Talented Online Anzac Day: Why The Other Eight Months Deserve The Same Recognition As The Landing Samai King Gifted and Talented Online rom its early beginnings in 1916, Anzac Day and the associated Anzac legend have come to be an essential part of Australian culture. Our history of the Gallipoli campaign lacks a consensus view as there are many Fdifferent interpretations and accounts competing for our attention. By far the most well-known event of the Gallipoli campaign is the landing of the ANZAC forces on the 25th of April, 1915. Our celebration of, and obsession with, just one single day of the campaign is a disservice to the memory of the men and women who fought under the Anzac banner because it dismisses the complexity and drudgery of the Gallipoli campaign: the torturous trenches and the ever present fear of snipers. Our ‘Anzac’ soldier is a popularly acclaimed model of virtue, but is his legacy best represented by a single battle? Many events throughout the campaign are arguably more admirable than the well-lauded landing, for example the Battle for Lone Pine. Almost four times as many men died in the period of the Battle of Lone Pine than during the Landing. Statistics also document the surprisingly successful evacuation - they lost not even a single soldier to combat. We have become so enamored by the ‘Landing’ that it is now more celebrated and popular than Remembrance Day which commemorates the whole of the First World War in which Anzacs continued to serve. -

Beyond Gallipoli

Beyond Gallipoli New Perspectives on Anzac Edited by Raelene Frances and Bruce Scates © Copyright 2016 Copyright of this collection in its entirety is held by Raelene Frances and Bruce Scates. Copyright of the individual chapters is held by the respective chapter authors. All rights reserved. Apart from any uses permitted by Australia’s Copyright Act 1968, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the copyright owners. Inquiries should be directed to the publisher. Monash University Publishing Matheson Library and Information Services Building 40 Exhibition Walk Monash University Clayton, Victoria 3800, Australia www.publishing.monash.edu Monash University Publishing brings to the world publications which advance the best traditions of humane and enlightened thought. Monash University Publishing titles pass through a rigorous process of independent peer review. www.publishing.monash.edu/books/bg-9781925495102.html Series: Australian History Series Editor / Board: Sean Scalmer Design: Les Thomas Front cover image: Exhibition Giant, Gallipoli: The Scale of Our War, Private Colin Airlie Warden (1890–1915), Auckland Infantry Battalion. Photograph by Michael Hall. Courtesy of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Back cover image: ‘Peace’ ferry, with warship in the background, Anzac Cove, 2015. Photo by Bruce Scates.. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Title: Beyond Gallipoli : new perspectives on Anzac / edited by Raelene Frances, Bruce Scates. ISBN: 9781925495102 (paperback) Subjects: World War, 1914-1918--Social aspects--Australia. World War, 1914-1918--Social aspects--New Zealand. World War, 1914-1918--Social aspects--Turkey. War and society. Other Creators/Contributors: Frances, Raelene, editor. -

Anzac Day Media Style Guide - Centenary Edition 2016

Anzac Day Media Style Guide - Centenary Edition 2016 Contents (click on the headings below to navigate the guide) Foreword to the 2016 edition ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Foreword to the 2015 edition ........................................................................................................................................... 6 About this Guide ............................................................................................................................................................... 7 Editorial Advisory Board................................................................................................................................................ 8 Further Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................................................... 9 Your Feedback is Welcome ........................................................................................................................................... 9 Getting Started ................................................................................................................................................................ 10 Anzac/ANZAC .............................................................................................................................................................. 10 Anzac Day or ANZAC Day? ......................................................................................................................................... -

The Colours of the Fleet

THE COLOURS OF THE FLEET TCOF BRITISH & BRITISH DERIVED ENSIGNS ~ THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE WORLDWIDE LIST OF ALL FLAGS AND ENSIGNS, PAST AND PRESENT, WHICH BEAR THE UNION FLAG IN THE CANTON “Build up the highway clear it of stones lift up an ensign over the peoples” Isaiah 62 vv 10 Created and compiled by Malcolm Farrow OBE President of the Flag Institute Edited and updated by David Prothero 15 January 2015 © 1 CONTENTS Chapter 1 Page 3 Introduction Page 5 Definition of an Ensign Page 6 The Development of Modern Ensigns Page 10 Union Flags, Flagstaffs and Crowns Page 13 A Brief Summary Page 13 Reference Sources Page 14 Chronology Page 17 Numerical Summary of Ensigns Chapter 2 British Ensigns and Related Flags in Current Use Page 18 White Ensigns Page 25 Blue Ensigns Page 37 Red Ensigns Page 42 Sky Blue Ensigns Page 43 Ensigns of Other Colours Page 45 Old Flags in Current Use Chapter 3 Special Ensigns of Yacht Clubs and Sailing Associations Page 48 Introduction Page 50 Current Page 62 Obsolete Chapter 4 Obsolete Ensigns and Related Flags Page 68 British Isles Page 81 Commonwealth and Empire Page 112 Unidentified Flags Page 112 Hypothetical Flags Chapter 5 Exclusions. Page 114 Flags similar to Ensigns and Unofficial Ensigns Chapter 6 Proclamations Page 121 A Proclamation Amending Proclamation dated 1st January 1801 declaring what Ensign or Colours shall be borne at sea by Merchant Ships. Page 122 Proclamation dated January 1, 1801 declaring what ensign or colours shall be borne at sea by merchant ships. 2 CHAPTER 1 Introduction The Colours of The Fleet 2013 attempts to fill a gap in the constitutional and historic records of the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth by seeking to list all British and British derived ensigns which have ever existed. -

A Critique of the Militarisation of Australian History and Culture Thesis: the Case of Anzac Battlefield Tourism

A Critique of the Militarisation of Australian History and Culture Thesis: The Case of Anzac Battlefield Tourism Jim McKay, Centre for Critical and Cultural Studies, University of Queensland This special issue on travel from Australia through a multidisciplinary lens is particularly apposite to the increasing popularity of Anzac battlefield tourism. Consider, for instance, the Dawn Service at Gallipoli in 2015, which will be the highlight of the commemoration of the Anzac Centenary between 2014 and 2018 (Anzac Centenary 2012). Australian battlefield tourism companies are already fully booked for this event, which is forecast to be ‘the largest peacetime gathering of Australians outside of Australia’ (Kelly 2011). Some academics have argued that rising participation in Anzac battlefield tours is symptomatic of a systemic and unrelenting militarisation of Australian history and culture. Historians Marilyn Lake, Mark McKenna and Henry Reynolds are arguably the most prominent proponents of this line of reasoning. According to McKenna: It seems impossible to deny the broader militarisation of our history and culture: the surfeit of jingoistic military histories, the increasing tendency for military displays before football grand finals, the extension of the term Anzac to encompass firefighters and sporting champions, the professionally stage-managed event of the dawn service at Anzac Cove, the burgeoning popularity of battlefield tourism (particularly Gallipoli and the Kokoda Track), the ubiquitous newspaper supplements extolling the virtues of soldiers past and present, and the tendency of the media and both main political parties to view the death of the last World War I veterans as significant national moments. (2007) In the opening passage of their book, What’s Wrong With Anzac? The Militarisation of Australian History (henceforth, WWWA), to which McKenna contributed a chapter, Lake and Reynolds also avowed that militarisation was a pervasive and inexorable PORTAL Journal of Multidisciplinary International Studies, vol. -

'The First Casualty When War Comes Is Truth'

‘The First Casualty When War Comes is Truth’ 54 ‘The First Casualty When War Comes is Truth’: Neglected Atrocity in First World War Australian Memory Emily Gallagher Fourth Year Undergraduate, University of Notre Dame ‘The first casualty when war comes is truth’1 Hiram W. Johnson It is assumed, at least in the West, that the glorification of war is a thing of the past. Even more widely accepted is the perception that modern veneration honours the dead without bias or prejudice. In fact, the rich tapestry of the ANZAC legend glorifies war and readily rejects its associated horrors, projecting constructions of heroism and virtue onto national memory. Exploring the popular perception that inhumane war practices are inherently non-Western, this paper assesses the persisting silence on the grotesque experiences of soldiers in war. An examination of the nature and use of chemical warfare in World War One (WWI) and historiographical analysis of Australian scholarship on WWI will form the foundation of case evidence. Additionally, the psychological analysis of ‘joyful killing’ will be discussed as a potential framework through which modern commemoration can expose past embellishments. Bruce Scates’ Return to Gallipoli considers death and the ‘narrowed’ nature of ANZAC war commemoration. He argues that commemorative services perform a conservative political purpose, 1 Attributed to Senator Hiram Johnson in 1917, this quote originates from Samuel Johnson in 1758. See Suzy Platt (ed.), Respectfully Quoted: a Dictionary of Quotations Requested from the Congressional Research service(Washington: Library of Congress, 1989), 360. 55 history in the making vol. 4 no. 1 where personal mourning is displaced with sentiments of patriotism and sacrifice.2 Pronouncing WWI the ‘great imaginative event’ of the century, Peter Hoffenberg argues that Australians have sought to comprehend the catastrophe of war through references to landscape.3 Certainly, the WWI cemeteries on the Western Front strongly support this venture. -

Traces of War Program

Narratives of War Research Group 2013 Symposium Traces of War Program 20 – 22 November 2013, Amy Wheaton Building, Magill Campus, University of South Australia Free entry - Light refreshments provided The title for the Narratives of War Symposium takes its theme from the way artefacts, diaries, media, art, music, memorabilia — letters, objects, the trappings of previous existence — indeed all manner of things, might be reflections and evidence of the traces left by war and conflict, and any aftermath and perhaps ensuing peace. The NOW Biennial Symposium is also open to the community and aims to offer interested community groups the chance to participate in current research and writing by scholars and researchers who will offer a broad range of papers and presentations. GUEST SPEAKERS Professor Peter Stanley Professor Peter Stanley is Research Professor at the University of New South Wales, Canberra’s Australian Centre for the Study of Armed Conflict and Society and former head of the Research Centre at the National Museum of Australia and former Principal Historian at the Australian War Memorial. Peter is one of Australia's most active military-social historians. He has published 25 books, mainly in the field of Australian military history (such as Tarakan: an Australian Tragedy or Quinn's Post, Anzac, Gallipoli or Invading Australia), but also in medical history (For Fear of Pain: British Surgery 1790-1850), British India (White Mutiny: British Military Culture in India 1825-75), British military history (Commando to Colditz) and bushfires (Black Saturday at Steels Creek). Professor Bruce Scates Professor Bruce Scates is a graduate of Monash University and the University of Melbourne. -

ANZAC DAY EDITION 2016 Lest We Forget

20162014 1915 Lest we forget ` FOOTBALL ROUND 3 ANZAC DAY EDITION 2016 SENIORS / RESERVES UNDER 19’s Saturday, April 23 Saturday, April 23 Berwick v Doveton Berwick A v Doveton Beaconsfield v Narre Warren Beaconsfield v Narre Warren A Officer SFC v Pakenham Officer SFC v Pakenham Hampton Park BYE Berwick B BYE Monday, April 25 Monday, April 25 Tooradin-Dalmore v Cranbourne Narre Warren B v Cranbourne MAJOR PARTNERS SUPPORT PARTNERS PREFERRED APPAREL PROVIDERS FROM THE SEFNL DESK They shall grow not old As we that are left grow old Age shall not weary them Nor the years condemn At the going down of the sun and in the morning We will remember them Lest we forget 20162015 1915 IN THIS EDITION . A Message from AFL South East 2 Round 2 Review 8 A Message from AFL Victoria 3 Round 3 Preview 9 Round 2 Results 4 Senior/Reserve Team Lists 10 Football Ladders 5 Under 19 Team Lists 27 Umpires Message 7 2016 Football Fixture 32 Phone: (03) 5221 4408 Address: 203 Malop Street, Geelong VIC 3220 www.adcellgroup.com.au A Division of Adcell Group OFFICIAL PUBLISHER OF THE SOUTH EAST FOOTBALL NETBALL LEAGUE RECORD All editorial and photographs prepared by AFL South East Media Relations Officer, including articles and those contributors, published in the SEFNL Record, are subject to copyright laws and cannot be reproduced without the permission of AFL South East. Address all correspondence to: AFL South East, PO BOX 5154, Cranbourne VIC 3977. Ph: (03) 5995 5060 SEFNL | FOOTBALL 1 A MESSAGE FROM A MESSAGE FROM AFL SOUTH EAST AFL VICTORIA Football has always played an important carried their thoughts vividly back to those role within our armed services personnel; happy days when football was played in Remembering our Anzacs enhancing fitness, building morale, certain Melbourne suburbs they had called providing a physical outlet, negating home’. -

The Simpson Prize: History Or Civics? Table of Contents

1 The Simpson Prize: history or civics? David Stephens and Steve Flora Table of contents What is the Simpson Prize?................................................................................................................. 1 What questions are asked? ................................................................................................................. 2 Who runs the Prize? ............................................................................................................................ 3 Which schools have entered students for the Prize? ......................................................................... 3 How many students have entered for the Prize? ............................................................................... 4 Which schools have provided the winners of the Prize? .................................................................... 4 What is the standard of entries? ........................................................................................................ 6 What is the significance of the 2015 question? .................................................................................. 8 What is the future of the Prize? .......................................................................................................... 9 Conclusion ......................................................................................................................................... 10 Appendix: Simpson Prize questions 1999-2014 ............................................................................... -

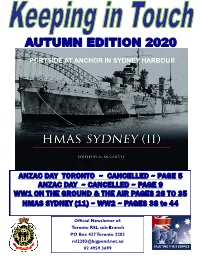

Autumn Edition 2020

AUTUMN EDITION 2020 PORTSIDE AT ANCHOR IN SYDNEY HARBOUR ANZAC DAY TORONTO ~ CANCELLED ~ PAGE 5 ANZAC DAY ~ CANCELLED ~ PAGE 9 WW1 ON THE GROUND & THE AIR PAGES 26 TO 35 HMAS SYDNEY (11) ~ WW2 ~ PAGES 38 to 44 Official Newsletter of: Toronto RSL sub-Branch PO Box 437 Toronto 2283 [email protected] 02 4959 3699 Arcade Books 60 The Boulevarde Toronto ~ 49592800 Selling all types of pre-loved books and Books helping adults with reading and writing skills. In the arcade opposite Toronto Diggers. Closed Mondays Tues - Fri 9:00-5:00 - Sat 9:00 -1:00 In a time of need turn to someone you can trust FDA of NSW. Family Owned and Operated. (02) 49 731513 4959 1296 • All work done on the premises Pre Arranged Funeral Plan in • Alterations and Repairs Association with • Exclusive Bridal and Eveningwear Specialists • Blankets, Quilts, Curtains barbarakingfunerals.com.au From the Presidents Desk We have had a change of personnel within the Sub Branch Executive. After many years of service Ron decided he could no longer continue his role as President. His health has not been the best and the demands of both here and the Diggers Club were catching up. We at the Sub Branch pass on our gratitude and thanks for his years of dedicated service to helping veterans and families and in running and maintaining the office. Many of you may not realise just how hard it has been over the past 3 years and the amount of work required to maintain the Sub Branch, it has not been fun and at times very hard on Ron’s health. -

The Aim of the Club Is to Encourage Juvenile, Junior, Adult Singers and Musicians to Perform at Club Functions Or on Stage

The aim of the Club is to encourage juvenile, junior, adult singers and musicians to perform at Club functions or on stage. Also to promote country music in Townsville and the surrounding areas. TOWNSVILLE AND THURINGOWA COUNTRY MUSIC ASSOCIATION INC P.O.BOX 1518 Aitkenvale Mail Centre Aitkenvale Q4814 Mobile: 0417 199 744 Darryl Pitt Email: [email protected] PATRON: Councillor Ray Gartrell MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE PRESIDENT: Darryl Pitt 0417 199 744 VICE PRESIDENT: Shane Barratt 0407 178 741 SECRETARY: Maureen Pitt 4725 4756 TREASURER: Val Peters 4723 3661 MEMBER: Glenda Albert 0415 811 544 Appointed Positions MAGAZINE EDITOR: Beverley Davis 4788 0107 MUSIC CO-ORDINATOR: John Brent 0402 248 854 ASST MUSIC CO-ORD: Laurie Reilly 0448 957 747 PROPERTY OFFICER: Shane Barratt 0407 178 741 ASSISTAND SECRETARY: Glenda Albert 0415 811 544 ASSISTANT TREASURER: Glenda Albert 0415 811 544 PUBLICITY OFFICER: Veronica Barratt 0407 178 741 PUBLIC RELATIONS: Vacant 0415 880 841 YOUTH LIASON OFFICER: Sammy White 0450 721 094 WEB SITE www.ttcma.webs.com President’s Report for February G’Day All, Well 2016 has started in fine style, with the Members who went down to Tamworth making their mark with the best of them. Congratulations to you all. This year look to be another busy one as there are quite a few sausage sizzles, (thanks to all the workers who pitched in at the last minute for the one at Bunnings Domain). I would like to thank Bunnings, Intersport and Toyworld for their continued support. These sizzles are a good fundraiser for the club. We have two Pallarenda picnics organised, one in April and another in July.