Cracks in the Periodic Table

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution and Understanding of the D-Block Elements in the Periodic Table Cite This: Dalton Trans., 2019, 48, 9408 Edwin C

Dalton Transactions View Article Online PERSPECTIVE View Journal | View Issue Evolution and understanding of the d-block elements in the periodic table Cite this: Dalton Trans., 2019, 48, 9408 Edwin C. Constable Received 20th February 2019, The d-block elements have played an essential role in the development of our present understanding of Accepted 6th March 2019 chemistry and in the evolution of the periodic table. On the occasion of the sesquicentenniel of the dis- DOI: 10.1039/c9dt00765b covery of the periodic table by Mendeleev, it is appropriate to look at how these metals have influenced rsc.li/dalton our understanding of periodicity and the relationships between elements. Introduction and periodic tables concerning objects as diverse as fruit, veg- etables, beer, cartoon characters, and superheroes abound in In the year 2019 we celebrate the sesquicentennial of the publi- our connected world.7 Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported Licence. cation of the first modern form of the periodic table by In the commonly encountered medium or long forms of Mendeleev (alternatively transliterated as Mendelejew, the periodic table, the central portion is occupied by the Mendelejeff, Mendeléeff, and Mendeléyev from the Cyrillic d-block elements, commonly known as the transition elements ).1 The periodic table lies at the core of our under- or transition metals. These elements have played a critical rôle standing of the properties of, and the relationships between, in our understanding of modern chemistry and have proved to the 118 elements currently known (Fig. 1).2 A chemist can look be the touchstones for many theories of valence and bonding. -

Bioorganometallic Technetium and Rhenium Chemistry: Fundamentals for Applications

RadiochemistRy in switzeRland CHIMIA 2020, 74, No. 12 953 doi:10.2533/chimia.2020.953 Chimia 74 (2020) 953–959 © R. Alberto, H. Braband, Q. Nadeem Bioorganometallic Technetium and Rhenium Chemistry: Fundamentals for Applications Roger Alberto*, Henrik Braband, and Qaisar Nadeem Abstract: Due to its long half-life of 2.111×105 y, technetium, i.e. 99Tc, offers the excellent opportunity of combin- ing fundamental and ‘classical’ organometallic or coordination chemistry with all methodologies of radiochem- istry. Technetium chemistry is inspired by the applications of its short-lived metastable isomer 99mTc in molecular imaging and radiopharmacy. We present in this article examples about these contexts and the impact of purely basic oriented research on practical applications. This review shows how the chemistry of this element in the middle of the periodic system inspires the chemistry of neighboring elements such as rhenium. Reasons are given for the frequent observation that the chemistries of 99Tc and 99mTc are often not identical, i.e. compounds accessible for 99mTc, under certain conditions, are not accessible for 99Tc. The article emphasizes the importance of macroscopic technetium chemistry not only for research but also for advanced education in the general fields of radiochemistry. Keywords: Bioorganometallics · Molecular Imaging · Radiopharmacy · Rhenium · Technetium Roger Alberto obtained his PhD from the Qaisar Nadeem got his PhD from the ETH Zurich. He was an Alexander von University of the Punjab Lahore, Pakistan. Humboldt fellow in the group of W.A. He received the higher education commission Herrmann at the TU Munich and at the (HEC, Pakistan) fellowship during his PhD Los Alamos National Laboratory with and worked in theAlberto group, Department A Sattelberger. -

The Development of the Periodic Table and Its Consequences Citation: J

Firenze University Press www.fupress.com/substantia The Development of the Periodic Table and its Consequences Citation: J. Emsley (2019) The Devel- opment of the Periodic Table and its Consequences. Substantia 3(2) Suppl. 5: 15-27. doi: 10.13128/Substantia-297 John Emsley Copyright: © 2019 J. Emsley. This is Alameda Lodge, 23a Alameda Road, Ampthill, MK45 2LA, UK an open access, peer-reviewed article E-mail: [email protected] published by Firenze University Press (http://www.fupress.com/substantia) and distributed under the terms of the Abstract. Chemistry is fortunate among the sciences in having an icon that is instant- Creative Commons Attribution License, ly recognisable around the world: the periodic table. The United Nations has deemed which permits unrestricted use, distri- 2019 to be the International Year of the Periodic Table, in commemoration of the 150th bution, and reproduction in any medi- anniversary of the first paper in which it appeared. That had been written by a Russian um, provided the original author and chemist, Dmitri Mendeleev, and was published in May 1869. Since then, there have source are credited. been many versions of the table, but one format has come to be the most widely used Data Availability Statement: All rel- and is to be seen everywhere. The route to this preferred form of the table makes an evant data are within the paper and its interesting story. Supporting Information files. Keywords. Periodic table, Mendeleev, Newlands, Deming, Seaborg. Competing Interests: The Author(s) declare(s) no conflict of interest. INTRODUCTION There are hundreds of periodic tables but the one that is widely repro- duced has the approval of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and is shown in Fig.1. -

The Periodic Table of Elements

The Periodic Table of Elements 1 2 6 Atomic Number = Number of Protons = Number of Electrons HYDROGENH HELIUMHe 1 Chemical Symbol NON-METALS 4 3 4 C 5 6 7 8 9 10 Li Be CARBON Chemical Name B C N O F Ne LITHIUM BERYLLIUM = Number of Protons + Number of Neutrons* BORON CARBON NITROGEN OXYGEN FLUORINE NEON 7 9 12 Atomic Weight 11 12 14 16 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 SODIUMNa MAGNESIUMMg ALUMINUMAl SILICONSi PHOSPHORUSP SULFURS CHLORINECl ARGONAr 23 24 METALS 27 28 31 32 35 40 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 POTASSIUMK CALCIUMCa SCANDIUMSc TITANIUMTi VANADIUMV CHROMIUMCr MANGANESEMn FeIRON COBALTCo NICKELNi CuCOPPER ZnZINC GALLIUMGa GERMANIUMGe ARSENICAs SELENIUMSe BROMINEBr KRYPTONKr 39 40 45 48 51 52 55 56 59 59 64 65 70 73 75 79 80 84 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 RUBIDIUMRb STRONTIUMSr YTTRIUMY ZIRCONIUMZr NIOBIUMNb MOLYBDENUMMo TECHNETIUMTc RUTHENIUMRu RHODIUMRh PALLADIUMPd AgSILVER CADMIUMCd INDIUMIn SnTIN ANTIMONYSb TELLURIUMTe IODINEI XeXENON 85 88 89 91 93 96 98 101 103 106 108 112 115 119 122 128 127 131 55 56 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 CESIUMCs BARIUMBa HAFNIUMHf TANTALUMTa TUNGSTENW RHENIUMRe OSMIUMOs IRIDIUMIr PLATINUMPt AuGOLD MERCURYHg THALLIUMTl PbLEAD BISMUTHBi POLONIUMPo ASTATINEAt RnRADON 133 137 178 181 184 186 190 192 195 197 201 204 207 209 209 210 222 87 88 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 FRANCIUMFr RADIUMRa RUTHERFORDIUMRf DUBNIUMDb SEABORGIUMSg BOHRIUMBh HASSIUMHs MEITNERIUMMt DARMSTADTIUMDs ROENTGENIUMRg COPERNICIUMCn NIHONIUMNh -

The Oganesson Odyssey Kit Chapman Explores the Voyage to the Discovery of Element 118, the Pioneer Chemist It Is Named After, and False Claims Made Along the Way

in your element The oganesson odyssey Kit Chapman explores the voyage to the discovery of element 118, the pioneer chemist it is named after, and false claims made along the way. aving an element named after you Ninov had been dismissed from Berkeley for is incredibly rare. In fact, to be scientific misconduct in May5, and had filed Hhonoured in this manner during a grievance procedure6. your lifetime has only happened to Today, the discovery of the last element two scientists — Glenn Seaborg and of the periodic table as we know it is Yuri Oganessian. Yet, on meeting Oganessian undisputed, but its structure and properties it seems fitting. A colleague of his once remain a mystery. No chemistry has been told me that when he first arrived in the performed on this radioactive giant: 294Og halls of Oganessian’s programme at the has a half-life of less than a millisecond Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (JINR) before it succumbs to α -decay. in Dubna, Russia, it was unlike anything Theoretical models however suggest it he’d ever experienced. Forget the 2,000 ton may not conform to the periodic trends. As magnets, the beam lines and the brand new a noble gas, you would expect oganesson cyclotron being installed designed to hunt to have closed valence shells, ending with for elements 119 and 120, the difference a filled 7s27p6 configuration. But in 2017, a was Oganessian: “When you come to work US–New Zealand collaboration predicted for Yuri, it’s not like a lab,” he explained. that isn’t the case7. -

The Past and Future of the Periodic Table

The Past and Future of the Periodic Table This stalwart symbol of the field of chemistry always faces scrutiny and debate Eric R. Scerri t graces the walls of lecture halls making up one period. The lengths elements, Döbereiner found that the Iand laboratories of all types, from of periods vary: The first has two ele- weight of the middle element—such as universities to industry. It is one of ments, the next two eight each, then 18 selenium in the triad formed by sulfur, the most powerful icons of science. It and 32, respectively, for the next pairs selenium and tellurium—had an atom- captures the essence of chemistry in of periods. Vertical columns make up ic weight that was the approximate one elegant pattern. The periodic table groups, of which there are 18, based average of the weights of the other two provides a concise way of understand- on similar chemical properties, related elements. Sulfur’s atomic weight, in ing how all known chemical elements to the number of electrons in the outer Döbereiner’s time, was 32.239, where- react with one another and enter into shell of the atoms, also called the va- as tellurium’s was 129.243, the average chemical bonding, and it helps to ex- lence shell. For instance, group 17, the of which is 80.741, or close to the then- plain the properties of each element halogens, all lack one electron to fill measured value for selenium, 79.264. that make it react in such a fashion. their valence shells, all tend to acquire The importance of this discovery lay But the periodic system is so funda- electrons during reactions, and all form in the marrying of qualitative chemical mental, pervasive and familiar in the acids with hydrogen. -

Thermophysical Properties of the Lanthanide Sesquisulfides. III

Thermophysical properties of the lanthanide sesquisulfides. Ill. Determlnatlon of Schgttky and lattice heat-capacity contributions of y-phase Sm,S, and evaluation of the thermophysical properties of the y-phase Ln,S, subset Roey Shaviv”) and Edgar F. Westrum, Jr. Department of Chemistry, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-105.5 John. B. Gruber Department of Physics,San JoseState University, San Jose, California 95192-0106 8. J. Beaudry and P. E. Palmer Ames Laboratory, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa SOO1I-3020 (Received 18 October 1991;accepted 10 January 1992) We report the experimental heat capacity of y-phaseSm, S, and derived thermophysical properties at selectedtemperatures. The entropy, enthalpy increments, and Gibbs energy function are 21SOR, 3063R.K, and 11.23Rat 298.15K. The experimental heat capacity is made up of lattice and electronic (Schottky ) contributions. The lattice contribution is determined for all y-phaselanthanide sesquisulfides(Ln, S, ) using the Komada/Westrum model. The differencebetween the experimental heat capacity and the deducedlattice heat capacity is analyzed as the Schottky contribution. Comparisonsare made betweenthe calorimetric Schottky contributions and those determined basedon crystal-field electronic energy levels of Ln3 + ions in the lattice and betweenthe Schottky contributions obtained from the empirical volumetric priority approach and from the Komada/Westrum theoretical approach. Predictions for the thermophysical properties of y-phaseEu, S, and y-phasePm, S, (unavailable for experimental determination) are also presented. INTRODUCTION by the volumetric scheme’ for estimation of lattice heat ca- The first‘two papersin this series’**describe the experi- pacity was found to be useful-as it was for the bixbyite mental determination and the resolution of the heat capaci- sesquioxides.’ ties of La2S3,’ Ce,S,,’ Nd2S3,’ Gd,S,,’ Pr2S3,* Tb2S3,* The main task in the analysisof the heat-capacityvalues and Dy, S, (Ref. -

Quest for Superheavy Nuclei Began in the 1940S with the Syn Time It Takes for Half of the Sample to Decay

FEATURES Quest for superheavy nuclei 2 P.H. Heenen l and W Nazarewicz -4 IService de Physique Nucleaire Theorique, U.L.B.-C.P.229, B-1050 Brussels, Belgium 2Department ofPhysics, University ofTennessee, Knoxville, Tennessee 37996 3Physics Division, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, Tennessee 37831 4Institute ofTheoretical Physics, University ofWarsaw, ul. Ho\.za 69, PL-OO-681 Warsaw, Poland he discovery of new superheavy nuclei has brought much The superheavy elements mark the limit of nuclear mass and T excitement to the atomic and nuclear physics communities. charge; they inhabit the upper right corner of the nuclear land Hopes of finding regions of long-lived superheavy nuclei, pre scape, but the borderlines of their territory are unknown. The dicted in the early 1960s, have reemerged. Why is this search so stability ofthe superheavy elements has been a longstanding fun important and what newknowledge can it bring? damental question in nuclear science. How can they survive the Not every combination ofneutrons and protons makes a sta huge electrostatic repulsion? What are their properties? How ble nucleus. Our Earth is home to 81 stable elements, including large is the region of superheavy elements? We do not know yet slightly fewer than 300 stable nuclei. Other nuclei found in all the answers to these questions. This short article presents the nature, although bound to the emission ofprotons and neutrons, current status ofresearch in this field. are radioactive. That is, they eventually capture or emit electrons and positrons, alpha particles, or undergo spontaneous fission. Historical Background Each unstable isotope is characterized by its half-life (T1/2) - the The quest for superheavy nuclei began in the 1940s with the syn time it takes for half of the sample to decay. -

Discovery of Cesium, Lanthanum, Praseodymium and Promethium Isotopes

Discovery of Cesium, Lanthanum, Praseodymium and Promethium Isotopes E. May, M. Thoennessen∗ National Superconducting Cyclotron Laboratory and Department of Physics and Astronomy, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA Abstract Currently, forty-one cesium, thirty-five lanthanum, thirty-two praseodymium, and thirty-one promethium, isotopes have been observed and the discovery of these isotopes is discussed here. For each isotope a brief synopsis of the first refereed publication, including the production and identification method, is presented. ∗Corresponding author. Email address: [email protected] (M. Thoennessen) Preprint submitted to Atomic Data and Nuclear Data Tables May 20, 2011 Contents 1. Introduction . 2 2. Discovery of 112−152Cs.................................................................................. 3 3. Discovery of 117−153La.................................................................................. 11 4. Discovery of 121−154Pr.................................................................................. 20 5. Discovery of 128−158Pm................................................................................. 27 6. Summary ............................................................................................. 35 References . 36 Explanation of Tables . 44 Table 1. Discovery of cesium, lanthanum, praseodymium and promethium isotopes. See page 44 for Explanation of Tables 45 1. Introduction The discovery of cesium, lanthanum, praseodymium and promethium isotopes is discussed as -

POST MENDELEEVIAN EVOLUTION of the PERIODIC TABLE (.Pdf)

Post Mendeleevian Evolution of the Periodic Table Gary Katz Periodic Round Table We are here in the centenary of the death of Mendeleev, whose life defines the epoch of the Periodic Table. To his memory we respectfully dedicate this, our plan to revitalize his invention, the Periodic Table. Since Mendeleev’s death in 1907, the only substantive changes in the Table have been the insertion of new elements; most fall into the eighth period with another seven in the main body of the Table, but only three of these are stable non-radioactive species. The quantum chemical results of Niels Bohr came along early in the century elucidating the electronic con- figurations of the atoms, explaining a great deal about what made the Periodic Table periodic. By mid century when Seaborg proposed an actinide series to parallel the lanthanide series, including a number of the new transuranium elements, the official Table we now have was es- sentially in place. It has not changed fundamentally since that time. In my previous paper “An Eight-period Table for the 21st Century” (1) I discussed the evolution of the 8-period concept and some of the people who have worked toward the goal of transforming the Periodic Table in this fashion. Since 2001, I have changed my terminology to agree with that of other writers: the 8-period table is now to be called the left-step table. This is a phrase coined by physical chemist Henry Bent, who proposed it back in the 80’s, and it allows for the expansion of the table into periods beyond the eighth—a critical area of future development for the Periodic Table. -

Periodic Table 1 Periodic Table

Periodic table 1 Periodic table This article is about the table used in chemistry. For other uses, see Periodic table (disambiguation). The periodic table is a tabular arrangement of the chemical elements, organized on the basis of their atomic numbers (numbers of protons in the nucleus), electron configurations , and recurring chemical properties. Elements are presented in order of increasing atomic number, which is typically listed with the chemical symbol in each box. The standard form of the table consists of a grid of elements laid out in 18 columns and 7 Standard 18-column form of the periodic table. For the color legend, see section Layout, rows, with a double row of elements under the larger table. below that. The table can also be deconstructed into four rectangular blocks: the s-block to the left, the p-block to the right, the d-block in the middle, and the f-block below that. The rows of the table are called periods; the columns are called groups, with some of these having names such as halogens or noble gases. Since, by definition, a periodic table incorporates recurring trends, any such table can be used to derive relationships between the properties of the elements and predict the properties of new, yet to be discovered or synthesized, elements. As a result, a periodic table—whether in the standard form or some other variant—provides a useful framework for analyzing chemical behavior, and such tables are widely used in chemistry and other sciences. Although precursors exist, Dmitri Mendeleev is generally credited with the publication, in 1869, of the first widely recognized periodic table. -

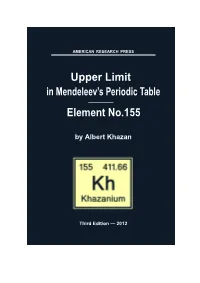

Upper Limit in Mendeleev's Periodic Table Element No.155

AMERICAN RESEARCH PRESS Upper Limit in Mendeleev’s Periodic Table Element No.155 by Albert Khazan Third Edition — 2012 American Research Press Albert Khazan Upper Limit in Mendeleev’s Periodic Table — Element No. 155 Third Edition with some recent amendments contained in new chapters Edited and prefaced by Dmitri Rabounski Editor-in-Chief of Progress in Physics and The Abraham Zelmanov Journal Rehoboth, New Mexico, USA — 2012 — This book can be ordered in a paper bound reprint from: Books on Demand, ProQuest Information and Learning (University of Microfilm International) 300 N. Zeeb Road, P. O. Box 1346, Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346, USA Tel.: 1-800-521-0600 (Customer Service) http://wwwlib.umi.com/bod/ This book can be ordered on-line from: Publishing Online, Co. (Seattle, Washington State) http://PublishingOnline.com Copyright c Albert Khazan, 2009, 2010, 2012 All rights reserved. Electronic copying, print copying and distribution of this book for non-commercial, academic or individual use can be made by any user without permission or charge. Any part of this book being cited or used howsoever in other publications must acknowledge this publication. No part of this book may be re- produced in any form whatsoever (including storage in any media) for commercial use without the prior permission of the copyright holder. Requests for permission to reproduce any part of this book for commercial use must be addressed to the Author. The Author retains his rights to use this book as a whole or any part of it in any other publications and in any way he sees fit.