Britannia a New Sculpture of Iphigenia in Tauris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE SERPENT TRAIL11.3Km 7 Miles 1 OFFICIAL GUIDE

SOUTH DOWNS WALKS ST THE SERPENT TRAIL11.3km 7 miles 1 OFFICIAL GUIDE ! HELPFUL HINT NATIONAL PARK The A286 Bell Road is a busy crossing point on the Trail. The A286 Bell Road is a busy crossing point on the Trail. West of Bell Road (A286) take the path that goes up between the houses, then across Marley Hanger and again up between two houses on a tarmac path with hand rail. 1 THE SERPENT TRAIL HOW TO GET THERE From rolling hills to bustling market towns, The name of the Trail reflects the serpentine ON FOOT BY RAIL the South Downs National Park’s (SDNP) shape of the route. Starting with the serpent’s The Greensand Way (running from Ham The train stations of Haslemere, Liss, 2 ‘tongue’ in Haslemere High Street, Surrey; landscapes cover 1,600km of breathtaking Street in Kent to Haslemere in Surrey) Liphook and Petersfield are all close to the views, hidden gems and quintessentially the route leads to the ‘head’ at Black Down, West Sussex and from there the ‘body’ finishes on the opposite side of Haslemere Trail. Visit nationalrail.co.uk to plan English scenery. A rich tapestry of turns west, east and west again along High Street from the start of the Serpent your journey. wildlife, landscapes, tranquillity and visitor the greensand ridges. The trail ‘snakes’ Trail. The Hangers Way (running from attractions, weave together a story of Alton to the Queen Elizabeth Country Park by Liphook, Milland, Fernhurst, Petworth, BY BUS people and place in harmony. in Hampshire) crosses Heath Road Fittleworth, Duncton, Heyshott, Midhurst, Bus services run to Midhurst, Stedham, in Petersfield just along the road from Stedham and Nyewood to finally reach the Trotton, Nyewood, Rogate, Petersfield, Embodying the everyday meeting of history the end of the Serpent Trail on Petersfield serpent’s ‘tail’ at Petersfield in Hampshire. -

CDAS – Chairman's Monthly Letter – March 2020 Fieldwork We Still Plan to Do the Geophysical Survey at Fishbourne Once

CDAS – Chairman’s Monthly Letter – March 2020 Fieldwork We still plan to do the geophysical survey at Fishbourne once the weather improves and the field starts to dry out. Coastal Monitoring Following the visit to Medmerry West in January we made a visit to Medmerry East. Recent storms had made a big change to the landscape. As on our last visit to the west side it was possible to walk across the breach at low tide. Some more of the Coastguard station has been exposed. However one corner has now disappeared. It was good that Hugh was able to create the 3D Model when he did. We found what looks like a large fish trap with two sets of posts running in a V shape, each arm being about 25 metres long. The woven hurdles were clearly visible. Peter Murphy took a sample of the timber in case there is an opportunity for radiocarbon dating. We plan to return to the site in March to draw and record the structure. When we have decided on a date for this work I will let Members know. Condition Assessment – Thorney Island The annual Condition Assessment of the WW2 sites on Thorney Island will be on Tuesday 10th March, meeting at 09:30 at the junction of Thorney Road and Thornham Lane (SU757049). If you would like to join us and want to bring a car onto the base you need to tell us in advance, so please email the make, model, colour and registration number of your car to [email protected] by Friday 6 March. -

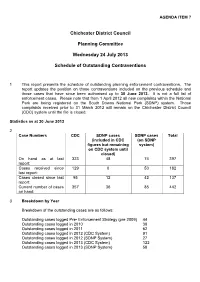

Schedule of Outstanding Contraventions

AGENDA ITEM 7 Chichester District Council Planning Committee Wednesday 24 July 2013 Schedule of Outstanding Contraventions 1 This report presents the schedule of outstanding planning enforcement contraventions. The report updates the position on those contraventions included on the previous schedule and those cases that have since been authorised up to 30 June 2013. It is not a full list of enforcement cases. Please note that from 1 April 2012 all new complaints within the National Park are being registered on the South Downs National Park (SDNP) system. Those complaints received prior to 31 March 2012 will remain on the Chichester District Council (CDC) system until the file is closed. Statistics as at 30 June 2013 2 Case Numbers CDC SDNP cases SDNP cases Total (included in CDC (on SDNP figures but remaining system) on CDC system until closed) On hand as at last 323 48 74 397 report: Cases received since 129 0 53 182 last report: Cases closed since last 95 12 42 137 report: Current number of cases 357 36 85 442 on hand: 3 Breakdown by Year Breakdown of the outstanding cases are as follows: Outstanding cases logged Pre- Enforcement Strategy (pre 2009) 44 Outstanding cases logged in 2010 38 Outstanding cases logged in 2011 62 Outstanding cases logged in 2012 (CDC System) 91 Outstanding cases logged in 2012 (SDNP System) 27 Outstanding cases logged in 2013 (CDC System) 122 Outstanding cases logged in 2013 (SDNP System) 58 4 Performance Indicators Financial Year 2013-2014 CDC Area Only a Acknowledge complaints within 5 days of receipt 92 -

The Serpent Trail 2 the SERPENT TRAIL GUIDE the SERPENT TRAIL GUIDE 3

The Serpent Trail 2 THE SERPENT TRAIL GUIDE THE SERPENT TRAIL GUIDE 3 Contents THE SERPENT TRAIL The Serpent Trail ...........................................3 6. Henley to Petworth, via Bexleyhill, Explore the heathlands of the South Downs National Park by Wildlife ..........................................................4 River Common and Upperton ............. 22 Heathland timeline .......................................8 7. Petworth to Fittleworth ........................ 24 following the 65 mile/106 km long Serpent Trail. Heathland Today ........................................ 10 8. Hesworth Common, Lord’s Piece and Discover this beautiful and internationally The name of the Trail reflects the serpentine Burton Park ........................................... 26 Heathland Stories Through Sculpture ....... 10 rare lowland heath habitat, 80% of which shape of the route. Starting with the serpent’s 9. Duncton Common to Cocking has been lost since the early 1800s, often head and tongue in Haslemere and Black 1. Black Down to Marley Common ......... 12 Causeway ............................................. 28 through neglect and tree planting on Down, the ‘body’ turns west, east and west 2. Marley Common through Lynchmere 10. Midhurst, Stedham and Iping previously open areas. Designed to highlight again along the greensand ridges. The Trail and Stanley Commons to Iron Hill ...... 14 Commons ............................................. 30 the outstanding landscape of the greensand ‘snakes’ by Liphook, Milland, Fernhurst, 3. From Shufflesheeps to Combe Hill hills, their wildlife, history and conservation, Petworth, Fittleworth, Duncton, Heyshott, 11. Nyewood to Petersfield ....................... 32 via Chapel Common ............................ 16 the Serpent Trail passes through the purple Midhurst, Stedham and Nyewood to finally Heathlands Reunited Partnership .............. 34 4. Combe Hill, Tullecombe, through heather, green woods and golden valleys of reach the serpent’s ‘tail’ at Petersfield in Rondle Wood to Borden Lane ........... -

PUBLIC OBSERVING NIGHTS the William D. Mcdowell Observatory

THE WilliamPUBLIC D. OBSERVING mcDowell NIGHTS Observatory FREE PUBLIC OBSERVING NIGHTS WINTER Schedule 2019 December 2018 (7PM-10PM) 5th Mars, Uranus, Neptune, Almach (double star), Pleiades (M45), Andromeda Galaxy (M31), Oribion Nebula (M42), Beehive Cluster (M44), Double Cluster (NGC 869 & 884) 12th Mars, Uranus, Neptune, Almach (double star), Pleiades (M45), Andromeda Galaxy (M31), Oribion Nebula (M42), Beehive Cluster (M44), Double Cluster (NGC 869 & 884) 19th Moon, Mars, Uranus, Neptune, Almach (double star), Pleiades (M45), Andromeda Galaxy (M31), Oribion Nebula (M42), Beehive Cluster (M44), Double Cluster (NGC 869 & 884) 26th Moon, Mars, Uranus, Neptune, Almach (double star), Pleiades (M45), Andromeda Galaxy (M31), Oribion Nebula (M42), Beehive Cluster (M44), Double Cluster (NGC 869 & 884)? January 2019 (7PM-10PM) 2nd Moon, Mars, Uranus, Neptune, Sirius, Almach (double star), Pleiades (M45), Orion Nebula (M42), Open Cluster (M35) 9th Mars, Uranus, Neptune, Sirius, Almach (double star), Pleiades (M45), Orion Nebula (M42), Open Cluster (M35) 16 Mars, Uranus, Neptune, Sirius, Almach (double star), Pleiades (M45), Orion Nebula (M42), Open Cluster (M35) 23rd, Moon, Mars, Uranus, Neptune, Sirius, Almach (double star), Pleiades (M45), Andromeda Galaxy (M31), Orion Nebula (M42), Beehive Cluster (M44), Double Cluster (NGC 869 & 884) 30th Moon, Mars, Uranus, Neptune, Sirius, Almach (double star), Pleiades (M45), Andromeda Galaxy (M31), Orion Nebula (M42), Beehive Cluster (M44), Double Cluster (NGC 869 & 884) February 2019 (7PM-10PM) 6th -

Black Sea-Caspian Steppe: Natural Conditions 20 1.1 the Great Steppe

The Pechenegs: Nomads in the Political and Cultural Landscape of Medieval Europe East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450 General Editors Florin Curta and Dušan Zupka volume 74 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ecee The Pechenegs: Nomads in the Political and Cultural Landscape of Medieval Europe By Aleksander Paroń Translated by Thomas Anessi LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Publication of the presented monograph has been subsidized by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education within the National Programme for the Development of Humanities, Modul Universalia 2.1. Research grant no. 0046/NPRH/H21/84/2017. National Programme for the Development of Humanities Cover illustration: Pechenegs slaughter prince Sviatoslav Igorevich and his “Scythians”. The Madrid manuscript of the Synopsis of Histories by John Skylitzes. Miniature 445, 175r, top. From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. Proofreading by Philip E. Steele The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://catalog.loc.gov/2021015848 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. -

2 Park Cottages

2 PARK COTTAGES VIEWING AND FURTHER DETAILS FROM THE Barrington & Company would like to inform all prospective SOLE AGENTS purchasers that these particulars have been prepared in good faith and that all descriptions, photographs, floor plans and MARKET SQUARE HOUSE land plans are given for guidance purposes only. Any PETWORTH, WEST SUSSEX GU28 0AH measurements or distances are a guide and should not be Tel: Petworth (01798) 342242 Fax: (01798) 342645 relied upon. We have not surveyed the property or tested any of the appliances or services. These particulars do not [email protected] form part of any contract in relation to the sale. www.barringtonandco.com 2 PARK COTTAGES, SCHOOL LANE, FITTLEWORTH, WEST SUSSEX, RH20 1JB. A LIGHT AND SPACIOUS MID-TERRACED HOUSE, QUIETLY SITUATED AND CLOSE TO VILLAGE SHOP AND SCHOOL. ATTIC ROOM WITH POTENTIAL. PRICE GUIDE £330,000 FREEHOLD OPEN PLAN KITCHEN, DINING AREA AND SITTING AREA, CLOAKROOM, 2 DOUBLE BEDROOMS, ATTIC ROOM WITH LOFT LADDER ACCESS, GAS FIRED CENTRAL HEATING, REAR GARDEN, 2 PARKING SPACES. DIRECTIONS: DESCRIPTION: Leave Petworth on the Fittleworth/Pulborough road Built in 2014 with elevations of mellow brick under a (A283) and proceed for about one and a half miles until clay tiled roof, the property is in the middle of a terrace the T junction then turn left (still on the A283) and follow of three houses set well back from School Lane and the road towards Fittleworth. After sharp right bend the with ample parking. The ground floor internal layout is road straightens into The Fleet, take the next right into open plan and offers a light and spacious living area School Lane and the property will be found on the right with a well appointed kitchen (with integral appliances), just past the village shop and opposite School Close on generous dining area and sitting area with bi-fold doors the left. -

DISCOVERING SUSSEX Hard Copy £2

hard copy DISCOVERING SUSSEX £2 SUMMER 2020 WELCOME These walks are fully guided by experienced leaders who have a great love and knowledge of the Sussex countryside. There is no ‘club’ or membership and they are freely open to everyone. The walks take place whatever the weather, but may be shortened by the leader in view of conditions on the day. There is no need to book. Simply turn up in good time and enjoy. The time in the programme is when the walk starts - not the time you should think about getting your boots on. There is no fixed charge for any of the local walks, but you may like to contribute £1 to the leader’s costs - which will always be gratefully received ! If you’re not sure about any of the details in this programme please feel free to contact the appropriate leader a few days in advance. Grid References (GR.) identify the start point to within 100m. If you’re not sure how it works log on to:- http://www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/docs/support/guide-to-nationalgrid.pdf Public transport Dogs on Gets a Accompanied to start point lead welcome bit hilly children welcome Toilets on Bring a Bring a Pub en-route the walk snack picnic lunch or at finish TAKE CARE Listen to the leader’s advice at the start of the walk. Stay between the leader and the back-marker. If you are going to leave the walk for any reason tell someone. Take care when crossing roads – do not simply follow the person in front of you. -

The Crimean Tatar Question: a Prism for Changing Nationalisms and Rival Versions of Eurasianism*

The Crimean Tatar Question: A Prism for Changing Nationalisms and Rival Versions of Eurasianism* Andrew Wilson Abstract: This article discusses the ongoing debates about Crimean Tatar identity, and the ways in which the Crimean Tatar question has been crucial to processes of reshaping Ukrainian identity during and after the Euromaidan. The Crimean Tatar question, it is argued, is a key test in the struggle between civic and ethnic nationalism in the new Ukraine. The article also looks at the manner in which the proponents of different versions of “Eurasianism”—Russian, Volga Tatar, and Crimean Tatar—have approached the Crimean Tatar question, and how this affects the attitudes of all these ethnic groups to the Russian annexation of Crimea. Key words: Crimean Tatars, Euromaidan, Eurasianism, national identity, nationalism—civic and ethnic Introduction In the period either side of the Russian annexation of Crimea, the Crimean Tatar issue has become a lodestone for redefining the national identities of all the parties involved. The mainstream Crimean Tatar movement has been characterized by steadfast opposition first to the Yanukovych regime in Ukraine and then to Russian rule. This position has strengthened its longstanding ideology of indigenousness and special rights, but it has also * The author is extremely grateful to Ridvan Bari Urcosta for his invaluable help with research for this article, to Bob Deen and Zahid Movlazada at the OSCE HCNM, to Professor Paul Robert Magocsi, and to the anonymous reviewers who made useful comments and criticisms. 1 2 ANDREW WILSON belatedly cemented its alliance with Ukrainian nationalism. Meanwhile, Ukraine’s would‐be new supra‐ethnic civic identity draws heavily on the Crimean Tatar contribution. -

Fittleworth Parish Council

Fittleworth Parish Council DRAFT Minutes of the Parish Council Meeting held On 16th October 2017 at 7.00pm in the Pavilion Building. Present: Chris Welfare (CW) Chair, Mike Allin (MA), David Brittain (DB), Alison Welterveden (AW), Shelagh Morgan (SM), Mick Foote (MF), Robin Dunstan (RD) and Tony Broughton (TB) In attendance: Janet Duncton (JD) for item 3 and Louise Collis (Clerk) Members of public: David Gilders, Maria Gilders, Lucia Dean Taylor, Adrian Webb, Mike Waller Action by 1. Apologies for absence: Chris O’Callaghan (CO) 2. Minutes of the last meeting and matters arising The minutes of the previous meeting held on 18th September 2017 were approved as a correct record and signed by CW. DB was thanked for preparing the minutes. The Minutes were PROPOSED by AW and SECONDED by MF. 3. District / County Councillor reports i) Community Green Offer (CGO) WSCC have announced a Community Green Offer (CGO) Pilot Project which began on 16th October across the Chichester District. The CGO has been developed with the aim of assisting the City, Town and Parish Councils and Community Groups to volunteer to undertake a range of work to help maintain the highway including cutting and clearance. The closest “tool library” is the Fire Station in Midhurst. The CGO includes: • access to training • the loan of tools and other equipment • insurance cover (subject to certain conditions) • support from the area highways teams The CGO can assist communities with tasks you may already have in mind or may help progress altogether new ideas. It also provides an opportunity to undertake street scene maintenance and improvement work that may have been delivered by the former Community Support Team or Highway Rangers. -

Wild Walks in the West Weald Landscape

Natural Attractions: Wild Walks in the West Weald Landscape Taking Care of Sussex Welcome to the wonderful West Weald Landscape We encourage you to explore this beautiful natural area by enjoying Editor Rich Howorth ‘wild walks’ around the nature ‘hotspots’ of this internationally important Research Lesley Barcock environment. Design Neil Fletcher The West Weald Landscape extends over 240 square kilometres of West Front cover photo by Richard Cobden, Cowdray Colossus photo by Klauhar Sussex and south Surrey. It characterised by gently undulating terrain on Low Weald clay soils, framed by elevated acidic greensand hills on three sides and All other photos by Neil Fletcher and Rich Howorth the Upper Arun river valley in the east. © Sussex Wildlife Trust 2011 The high-quality traditional countryside of the West Weald is one of the finest All rights reserved lowland landscapes in Britain. Standing amongst the small fields and strips of woodland, peppered with historic small hamlets, you could be stepping back to medieval times or beyond, as much of the landscape remains fundamentally We are grateful to our partner organisations for providing valuable unchanged since then. information for this booklet. Woodland blankets one-third of the area, with two-thirds of this classified as Production supported by donations from ‘ancient’ in nature, making it one of the most wooded landscapes in Britain. The Tubney Charitable Trust, It includes natural areas akin to the ancient ‘wild wood’ that once covered South Downs National Park Authority, the whole country after the last Ice Age. A wide range of wildlife calls this Lisbet Rausing, Peter Baldwin, Dick Poole, landscape home, including numerous rare species such as the Lesser-spotted Bat & Ball Inn, Crown Inn (Chiddingfold), Foresters Arms, Hollist Woodpecker, Wood White butterfly and Barbastelle bat which are all regional Arms, Lurgashall Winery, Onslow Arms, Star Inn, Stonemasons Inn, specialities. -

Table of Contents

Electronic Antiquity 12.2 (May 2009) Article: Foulmouthed Shepherds: Sexual Overtones As a Sign of Urbanitas in Virgil’s Bucolica 2 and 3 Stefan van den Broeck [PDF 2.7 MB] [email protected] Reviews: Efstratios Sarischoulis, Schicksal, Götter und Handlungsfreiheit in den Epen Homers (Fate, Gods and the Freedom of Action in the Epic Poems of Homer). Franz Steiner Verlag Stuttgart, 2008. ISBN: 3515091688. 312pp. Reviewed by Lucas Fassnacht [PDF 109 KB] Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen, Germany [email protected] Genevieve Liveley and Patricia Salzman-Mitchell (eds.), Latin Elegy and Narratology: Fragments of Story (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2008), ISBN 0814204066. xiii + 288pp. Reviewed by Ian Fielding [PDF 333 KB] University of Warwick and University of Wisconsin-Madison ([email protected]) Gendered Dynamics in Latin Love Poetry, eds. Ronnie Ancona and Ellen Greene. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005. ISBN: 0801881986. 384pp. Reviewed by Hunter H. Gardner [PDF 183 KB] University of South Carolina [email protected] A Brief History of Ancient Astrology, by Roger Beck. Blackwell, 2007. ISBN 1-4051-1074-0. xiii + 159pp; Fig. 10, Tab. 4. Reviewed byJohn M. McMahon [PDF 261 KB] Le Moyne College [email protected] A History of the Later Roman Empire AD 284-641. The Transformation of the Ancient World, by Stephen Mitchell. Blackwell History of the Ancient World. Blackwell Publishing, 2007. ISBN: 1405108568. 469pp. Reviewed by Charles F Pazdernik [PDF 247 KB] Grand Valley State University [email protected] 1 FOULMOUTHED SHEPHERDS: SEXUAL OVERTONES AS A SIGN OF URBANITAS IN VIRGIL’S BUCOLICA 2 AND 3 Stefan van den Broeck [email protected] Abstract: This article argues that Virgil introduced sexual overtones, an urbane motif par excellence, in Bucolica 2 and 3 – the oldest of his bucolic poems - to forestall criticism from his intended audience: the Poetae Novi and their aficionados, who would have regarded bucolic poetry – however unjustly – as ‘rustic’.