Roman – AD 43-410

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blackboy Lane, Fishbourne, West Sussex Chichester Westview, 60 Blackboy Lane, Fishbourne, Chichester, West Sussex, PO18 8BE

Blackboy Lane, Fishbourne, West Sussex Chichester Westview, 60 Blackboy Lane, Fishbourne, Chichester, West Sussex, PO18 8BE Located on the edge of this popular village, a detached home (1,192 sq ft approx) with lovely west facing views and large garden. sitting room I kitchen/breakfast room I bathroom I 3 bedrooms I cloakroom | garden | off street parking | garage Freehold Description Westview benefits with a large and bright reception room with west facing bay window, kitchen/breakfast room, cloakroom, three bedrooms and a family bathroom. The property provides a large garden to the rear, mainly laid to lawn, along with a garden to the front. To the side there is a driveway providing off street parking along with access to a garage with workshop behind. Situation The property is located just on the perimeter of the village of Fishbourne, famous for the Roman Palace, overlooking open countryside to the front. The location is suited with some good local schools, public house, railway station and bus links. The village also has a sports recreation ground offering various activities. The cathedral city of Chichester lies two miles distant to the North East. The city offers an outstanding range of shopping and recreational facilities, which include the highly regarded Festival Theatre and nearby Goodwood Estate for golf, horse racing, flying and motor racing. Rail links are provided from the mainline station (as well as from Fishbourne) with direct services to London (Victoria), Brighton, Portsmouth and Gatwick Airport. Directions: From the A27 Fishbourne roundabout continue on the A259 and after approximately 1 mile turn right onto Blackboy Lane. -

CDAS – Chairman's Monthly Letter – March 2020 Fieldwork We Still Plan to Do the Geophysical Survey at Fishbourne Once

CDAS – Chairman’s Monthly Letter – March 2020 Fieldwork We still plan to do the geophysical survey at Fishbourne once the weather improves and the field starts to dry out. Coastal Monitoring Following the visit to Medmerry West in January we made a visit to Medmerry East. Recent storms had made a big change to the landscape. As on our last visit to the west side it was possible to walk across the breach at low tide. Some more of the Coastguard station has been exposed. However one corner has now disappeared. It was good that Hugh was able to create the 3D Model when he did. We found what looks like a large fish trap with two sets of posts running in a V shape, each arm being about 25 metres long. The woven hurdles were clearly visible. Peter Murphy took a sample of the timber in case there is an opportunity for radiocarbon dating. We plan to return to the site in March to draw and record the structure. When we have decided on a date for this work I will let Members know. Condition Assessment – Thorney Island The annual Condition Assessment of the WW2 sites on Thorney Island will be on Tuesday 10th March, meeting at 09:30 at the junction of Thorney Road and Thornham Lane (SU757049). If you would like to join us and want to bring a car onto the base you need to tell us in advance, so please email the make, model, colour and registration number of your car to [email protected] by Friday 6 March. -

New-Lipchis-Way-Route-Guide.Pdf

Liphook River Rother Midhurst South New Downs South Lipchis Way Downs LIPHOOK Midhurst RAMBLERS Town Council River Lavant Singleton Chichester Footprints of Sussex Pear Tree Cottage, Jarvis Lane, Steyning, West Sussex BN44 3GL East Head Logo design – West Sussex County Council West Wittering Printed by – Wests Printing Works Ltd., Steyning, West Sussex Designed by – [email protected] 0 5 10 km © 2012 Footprints of Sussex 0 5 miles Welcome to the New New Lipchis Way This delightful walking trail follows existing rights of way over its 39 mile/62.4 kilometre route from Liphook, on Lipchis Way the Hampshire/West Sussex border, to East Head at the entrance to Chichester Harbour through the heart of the South Downs National Park.. Being aligned north-south, it crosses all the main geologies of West Sussex from the greensand ridges, through Wealden river valleys and heathlands, to the high chalk downland and the coastal plain. In so doing it offers a great variety of scenery, flora and fauna. The trail logo reflects this by depicting the South Downs, the River Rother and Chichester Harbour. It can be walked energetically in three days, bearing in mind that the total ‘climb’ is around 650 metres/2,000 feet. The maps divide it into six sections, which although unequal in distance, break the route into stages that allow the possible use of public transport. There is a good choice of accommodation and restaurants in Liphook, Midhurst and Chichester, elsewhere there is a smattering of pubs and B&Bs – although the northern section is a little sparse in that respect. -

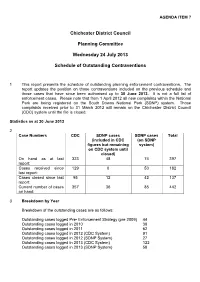

Schedule of Outstanding Contraventions

AGENDA ITEM 7 Chichester District Council Planning Committee Wednesday 24 July 2013 Schedule of Outstanding Contraventions 1 This report presents the schedule of outstanding planning enforcement contraventions. The report updates the position on those contraventions included on the previous schedule and those cases that have since been authorised up to 30 June 2013. It is not a full list of enforcement cases. Please note that from 1 April 2012 all new complaints within the National Park are being registered on the South Downs National Park (SDNP) system. Those complaints received prior to 31 March 2012 will remain on the Chichester District Council (CDC) system until the file is closed. Statistics as at 30 June 2013 2 Case Numbers CDC SDNP cases SDNP cases Total (included in CDC (on SDNP figures but remaining system) on CDC system until closed) On hand as at last 323 48 74 397 report: Cases received since 129 0 53 182 last report: Cases closed since last 95 12 42 137 report: Current number of cases 357 36 85 442 on hand: 3 Breakdown by Year Breakdown of the outstanding cases are as follows: Outstanding cases logged Pre- Enforcement Strategy (pre 2009) 44 Outstanding cases logged in 2010 38 Outstanding cases logged in 2011 62 Outstanding cases logged in 2012 (CDC System) 91 Outstanding cases logged in 2012 (SDNP System) 27 Outstanding cases logged in 2013 (CDC System) 122 Outstanding cases logged in 2013 (SDNP System) 58 4 Performance Indicators Financial Year 2013-2014 CDC Area Only a Acknowledge complaints within 5 days of receipt 92 -

WOODLAND GROVE BOXGROVE, WEST SUSSEX Goodwood Racecourse

WOODLAND GROVE BOXGROVE, WEST SUSSEX Goodwood Racecourse The South Downs Eartham East Lavant Funtington Goodwood WOODLAND GROVE Goodwood Circuit Boxgrove Hambrook Fontwell Southbourne Oving Fishbourne Chichester Bosham Barnham Donnington Chichester harbour Chichester Marina Itchenor Birdham Aldwick Bognor Regis West Wittering Sidlesham Pagham Bracklesham Bay WOODLAND GROVE BOXGROVE, WEST SUSSEX A DEVELOPMENT BY AGENTS www.domusea.com Chichester Office The Old Coach House, 14 West Pallant, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 1TB Tel +44 (0)1243 523723 www.todanstee.com The local area CITY COAST COUNTRYSIDE Chichester is one of the most sought after locations in the Less than 10 miles away is West Wittering, one of the UK’s Chichester is moments away from the rolling hills of South south it’s easy to see why. Chichester’s cathedral city is most striking unspoilt beaches and winner of a European Blue Downs National Park a recognised area of outstanding famous for its historical Roman and Anglo-Saxon heritage. Flag Award with views of Chichester harbour and the South beauty. The South Downs are popular for walking, horse riding Now, it’s the centre of culture and beauty with impressive Downs. West Wittering is a popular location for all the family and cycling, as well as simply enjoying the beautiful views. old buildings, a canal, two art galleries and renowned and also a favourite spot for kite surfers. The whole area is For the more adventurous, activities include paragliding, festival theatre. internationally recognised for its wildlife, birds and unique hang-gliding, golf, zorbing, mountain-boarding and a range of Chichester’s cosmopolitan feel brought to life by the city’s beauty. -

652 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

652 bus time schedule & line map 652 Chichester - East and West Wittering View In Website Mode The 652 bus line (Chichester - East and West Wittering) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Birdham: 2:40 PM (2) Chichester: 3:30 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 652 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 652 bus arriving. Direction: Birdham 652 bus Time Schedule 38 stops Birdham Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 2:40 PM Bishop Luffa School, Chichester Westgate, Chichester Tuesday 2:40 PM Grosvenor Road, Stockbridge Wednesday 2:40 PM Stockbridge Gardens, Stockbridge Thursday 2:40 PM Friday 2:40 PM Mile Pond Farm, Stockbridge Saturday Not Operational Dell Quay Road, Stockbridge The Black Horse, Apuldram Oak Lane, Appledram Civil Parish 652 bus Info Chichester Marina, Birdham Direction: Birdham Stops: 38 Business Park, Birdham Trip Duration: 34 min Line Summary: Bishop Luffa School, Chichester, Sidlesham Lane, Birdham Grosvenor Road, Stockbridge, Stockbridge Gardens, Stockbridge, Mile Pond Farm, Stockbridge, Dell Quay Road, Stockbridge, The Black Horse, Apuldram, Church Lane, Birdham Chichester Marina, Birdham, Business Park, Birdham, Sidlesham Lane, Birdham, Church Lane, Stores, Birdham Birdham, Stores, Birdham, The Bell Inn, Birdham, Mill, Somerley, Glen Nurseries, Somerley, Clayton Lane, The Bell Inn, Birdham Bracklesham Bay, Holdens Farm Caravan Park, Bell Lane, Birdham Civil Parish Bracklesham Bay, Clappers Lane, Bracklesham Bay, Middleton Close, Bracklesham -

Midhurst Sense of Place

Midhurst Sense of Place Produced as part of the Midhurst Vision by the Sense of Place Working Group September 2009 Cover image courtesy of Michael Chevis www.michaelchevis.com Contents 5 Foreword 6 Introduction 9 Context 12 Sense of Place Aims 13 Sense of Place Process 15 Activity 17 Physical Setting 20 Meaning 23 Sense of Place Definition 26 Place Making 31 Place Reading 36 Place Marketing 38 Potential Actions and Projects 39 Next Steps 40 Summary 42 Acknowledgements 43 Appendix 44 Key Design Principles 50 Terms of Reference 5 Foreword Like may towns throughout the UK, Midhurst has a range of unique qualities. Yet as a result of social and economic change it faces competition from neighbouring destinations like Chichester, Petersfield, Haselmere and Guildford. Chichester District Council recognised this problem and through a series of projects (aimed at supporting the local economy), engaged with the community to help identify key areas of development and regeneration. Whilst residents may have strong emotional links to their town or village, it is becoming increasingly important to understand and reveal the innate qualities and character of a place to attract visitors and compete with other towns in their region. However, it may be difficult to express what defines a ‘place’, but it is important to do so, to ensure that any support given by way of physical improvement or economic development, is appropriate and does not lead to the loss of individuality and regional identity. Understanding that Midhurst’s future prosperity is dependent on finding a way to manage change whilst maintaining a genuine and authentic sense of place, it became clear that a process was required to capture and articulate these unique aspects to help develop plans for the future. -

Parish Emergency Plan, a Copy of Which Wil L Be Lodged with C DC , Fits with the Inter - Agency Arrangements

PA RISH E MERGENC Y PLAN Adopted 3 December 2020 Date of revision Comments 1 INDEX Section 1 Emergency Arrangements Section 2 Emergency Coordinator Section 3 Volunteers Section 4 Council and Emergency Services Section 5 Advice for Emergency Situations Section 6 Parish Tem porary Accommoda tion Section 7 Services, Voluntary Groups, Media Section 8 Parish Councillors Section 9 District & County Councillors, Member of Parliament Section 10 Health & Safe ty Guidan ce Section 11 Local Map 2 Section 1 - EMER GENCY ARRANG EM ENTS M ajor Emergency The definition of a ‘Major Incident’ or ‘Major Emergency’ as supplied by CDC (CDC) is, “an incident endangering or likely to endanger life and property that to deal wit h would b e beyond the scope and facilities of normal da y to day operation al capabilities of those services responding”. Such incidents can occur anywhere at any time and often without warning. Response In normal circumstances the response to a major emer gency wou ld come from the inter - agency arrangements for malised between th e Emergency Services and C DC . Sussex Police would probably take the initial lead in co - ordinating the operation. In these circumstances the role of the Parish Council at a major emer gency aff ecting the Parish woul d be to assist the Emergency Services and CDC when requested by providing local knowledge and resources including organising local volunteers. Operations would come under the direction of the Police or District Council. It is theref or e important that this Parish Emergency Plan, a copy of which wil l be lodged with C DC , fits with the inter - agency arrangements. -

Chichester - East Broyle - Chichester Mon-Sat Department for Transport’S Local West Sussex

Catch the Bus Bus Frequencies Travel Plan Initiatives To find out when your next bus is due visit nextbuses.mobi or Information correct as of November 2014 In 2012, West Sussex County Council www.traveline.info Real time information, which enables you to track the secured £2.46 million from the expected arrival time of your bus, is available on an increasing number of services in 46/47 Chichester - East Broyle - Chichester Mon-Sat Department for Transport’s Local West Sussex. A Text-for-Times service is also available in parts of the county where 47 - Chichester, Bus Station R and Cathedral - East Broyle clockwise via St Paul’s Road, Sustainable Transport Fund (LSTF). you can obtain the arrival times of the next three buses by texting the bus stop Sherborne Road, Neville Road, Carleton Road, Worcester Road, Little Breach, St Paul’s Road The County Council, in partnership code to 84268 (charges apply). For further information about real time bus returns Chichester. 46 runs same route to East Broyle anti-clockwise. with Chichester District Council, is information visit www.westsussex.gov.uk/publictransport Monday to Saturday daytime every 30 minutes. now delivering a range of sustainable travel improvements in Chichester 50 Chichester - Graylingwell Park Daily and Horsham up to March 2015. Catch the Train R returns Chichester, Bus Station and Cathedral - Chichester University - Bloomfield Drive The package for Chichester includes: Travel by train can often work out to be cheaper than driving, particularly for Chichester regular journeys such as commuting. There are various on-line tools that can tell Monday to Sunday daytime and evenings every 30 minutes. -

A History of Chichester

A History of Chichester . Written on the occasion of our 250th Anniversary 1727 -1977 CONTENTS Preface. .. 5 The Establishment of Chichester. .. 7 Original Gran t . .. 8 Early Beginnings. .. 10 The Settlement of Chichester. .. 22 The Churches. .. 58 The Schools. .. 67 Old Home Day Celebrations. .. 80 Organizations. .. 87 Town Services. 102 Town Cemeteries. 115 Wars and Veterans. .. 118 3 PREFACE Our committee was formed to put into print some account of our town's history to commemorate the 250th anniversary of the granting of the original charter of our town. The committee has met over the past year and one-half and a large part of the data was obtained from the abstracts of the town records which were kept by Augustus Leavitt, Harry S. Kelley's history notes written in 1927 for the 200th anniversary and from the only sizable printed history of Chichester written by D. T. Brown in Hurd's History of Merrimack and Belknap Counties containing thirty seven pages. In researching we found that a whole generation is missing. It is regrettable that a history wasn't done before now when much that is now lost was within the mem- ory of some living who had the knowledge of our early history. Our thanks to the townspeople who have contributed either information, pic- tures, maps and written reports. It is our hope that the contents will be interesting and helpful to this and future generations. The Chichester History Committee Rev. H. Franklin Parker June E. Hatch Ruth E. Hammen 5 THE ESTABLISHMENT OF CHICHESTER Chichester was one of seven towns granted in New Hampshire in 1727 while Lieutenant Governor John Wentworth administered the affairs of the province, then a part of Massachusetts. -

Birdham Fruit Farm Martins Lane Birdham Chichester West Sussex PO20 7AU

Parish: Ward: Birdham West Wittering BI/19/00351/FUL Proposal Replacement dwelling. Alterations to house design - window to utility and minor increase in projection of south balcony. Re-use of existing building to provide multipurpose store. Erection of 3 bay garage and construction of swimming pool and hot tub - Variation of Condition 2 of planning permission BI/08/04567/FUL (APP/L3185/A/09/2093508 - Multi purpose store to include residential annex ancillary to dwelling house. Site Birdham Fruit Farm Martins Lane Birdham Chichester West Sussex PO20 7AU Map Ref (E) 482674 (N) 100437 Applicant Mr S Crossley RECOMMENDATION TO DEFER FOR SECTION 106 THEN PERMIT Note: Do not scale from map. For information only. Reproduced NOT TO from the Ordnance Survey Mapping with the permission of the SCALE controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office, Crown Copyright. License No. 100018803 1.0 Reason for Committee Referral 1.1 Parish Objection - Officer recommends Permit 2.0 The Site and Surroundings 2.1 The application site is located within the parish of Birdham, in a back land plot to the rear of properties known as Martins Lea and Martins Five. The property is a 2 storey detached dwelling, with the first floor set within the roof, served by dormer windows and rooflights. The existing property was permitted as a replacement dwelling, via an appeal, in 2009. A detached garage is located to the west of the dwelling. There is also a single storey building to the east which was the former dwelling on the site; when permission was granted for the replacement dwelling the retention of this building and its use as a multi- purpose store for purposes incidental to the main dwelling was also approved. -

DISCOVERING SUSSEX Hard Copy £2

hard copy DISCOVERING SUSSEX £2 SUMMER 2020 WELCOME These walks are fully guided by experienced leaders who have a great love and knowledge of the Sussex countryside. There is no ‘club’ or membership and they are freely open to everyone. The walks take place whatever the weather, but may be shortened by the leader in view of conditions on the day. There is no need to book. Simply turn up in good time and enjoy. The time in the programme is when the walk starts - not the time you should think about getting your boots on. There is no fixed charge for any of the local walks, but you may like to contribute £1 to the leader’s costs - which will always be gratefully received ! If you’re not sure about any of the details in this programme please feel free to contact the appropriate leader a few days in advance. Grid References (GR.) identify the start point to within 100m. If you’re not sure how it works log on to:- http://www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/docs/support/guide-to-nationalgrid.pdf Public transport Dogs on Gets a Accompanied to start point lead welcome bit hilly children welcome Toilets on Bring a Bring a Pub en-route the walk snack picnic lunch or at finish TAKE CARE Listen to the leader’s advice at the start of the walk. Stay between the leader and the back-marker. If you are going to leave the walk for any reason tell someone. Take care when crossing roads – do not simply follow the person in front of you.