(Included Separately) ABSTRACT 2 CHAPTER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shuggie Bain : Shortlisted for the Booker Prize 2020 Download Free

SHUGGIE BAIN : SHORTLISTED FOR THE BOOKER PRIZE 2020 Author: Douglas Stuart Number of Pages: 448 pages Published Date: 15 Apr 2021 Publisher: Pan MacMillan Publication Country: London, United Kingdom Language: English ISBN: 9781529064414 DOWNLOAD: SHUGGIE BAIN : SHORTLISTED FOR THE BOOKER PRIZE 2020 Shuggie Bain : Shortlisted for the Booker Prize 2020 PDF Book One page led to another and soon we realised we had created over 100 recipes and written 100 pages of nutrition advice. Have you already achieved professional and personal success but secretly fear that you have accomplished everything that you ever will. Translated from the French by Sir Homer Gordon, Bart. Bubbles in the SkyHave fun and learn to read and write English words the fun way. 56 street maps focussed on town centres showing places of interest, car park locations and one-way streets. These approaches only go so far. Hartsock situates narrative literary journalism within the broader histories of the American tradition of "objective" journalism and the standard novel. Margaret Jane Radin examines attempts to justify the use of boilerplate provisions by claiming either that recipients freely consent to them or that economic efficiency demands them, and she finds these justifications wanting. " -The New York Times Book Review "Empire of Liberty will rightly take its place among the authoritative volumes in this important and influential series. ) Of critical importance to the approach found in these pages is the systematic arranging of characters in an order best suited to memorization. Shuggie Bain : Shortlisted for the Booker Prize 2020 Writer About the Publisher Forgotten Books publishes hundreds of thousands of rare and classic books. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

US Regulatory and Tax Considerations for Offshore Funds Mark H

Journal of International Business and Law Volume 1 | Issue 1 Article 1 2002 US Regulatory and Tax Considerations for Offshore Funds Mark H. Barth Marco Blanco Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/jibl Recommended Citation Barth, Mark H. and Blanco, Marco (2002) "US Regulatory and Tax Considerations for Offshore Funds," Journal of International Business and Law: Vol. 1: Iss. 1, Article 1. Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/jibl/vol1/iss1/1 This Legal Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of International Business and Law by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Barth and Blanco: US Regulatory and Tax Considerations for Offshore Funds US Regulatory and Tax Considerations for Offshore Funds Mark H. Barth and Marco Blanco Curtis, Mallet-Prevost, Colt & Mosle LLP,* New York FirstPublished in THE CAPITAL GUIDE TO OFFSHOREFUNDS 2001, pp. 15-61 (ISI Publications,sponsored by Citco, eds. Sarah Barham and Ian Hallsworth) 2001. Offshore funds' continue to provide an efficient, innovative means of facilitating cross-border connections among investors, investment managers and investment opportunities. They are delivery vehicles for international investment capital, perhaps the most agile of economic factors of production, leaping national boundaries in the search for investment expertise and opportunities. Traditionally, offshore funds have existed in an unregulated state of grace; or disgrace, some would say. It is a commonplace to say that this is changing, both in the domiciles of offshore funds and in the various jurisdictions in which they seek investors, investments or managers. -

Introduction

I INTRODUCTION The objective of the thesis has been to explore the rootlessness in the major fictional works of V.S. Naipaul, the-Trinidad-born English author. The emphasis has been on the analysis of his writings, in which he has depicted the images of home, family and association. Inevitably, in this research work on V.S. Naipaul’s fiction, multiculturalism, homelessness (home away from home) and cultural hybridity has been explored. Naipaul has lost his roots no doubt, but he writes for his homeland. He is an expatriate author. He gives vent to his struggle to cope with the loss of tradition and makes efforts to cling to the reassurance of a homeland. Thepresent work captures the nuances of the afore-said reality. A writer of Indian origin writing in English seems to have an object, that is his and her imagination has to be there for his/her mother country. At the core of diaspora literature, the idea of the nation-state is a living reality. The diaspora literature, however, focuses on cultural states that are defined by immigration counters and stamps on one’s passport. The diaspora community in world literature is quite complex. It has shown a great mobility and adaptability as it has often been involved in a double act of migration from India to West Indies and Africa to Europe or America on account of social and political resources. Writers like Salman Rushdie, RohingtonMistry, Bahrain Mukherjee, and V.S. Naipaul write from their own experience of hanging in limbo between two identities: non-Indian and Indian. -

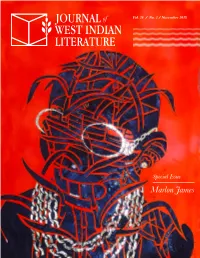

Marlon James Volume 26 Number 2 November 2018

Vol. 26 / No. 2 / November 2018 Special Issue Marlon James Volume 26 Number 2 November 2018 Published by the Departments of Literatures in English, University of the West Indies CREDITS Original image: Sugar Daddy #2 by Leasho Johnson Nadia Huggins (graphic designer) JWIL is published with the financial support of the Departments of Literatures in English of The University of the West Indies Enquiries should be sent to THE EDITORS Journal of West Indian Literature Department of Literatures in English, UWI Mona Kingston 7, JAMAICA, W.I. Tel. (876) 927-2217; Fax (876) 970-4232 e-mail: [email protected] Copyright © 2018 Journal of West Indian Literature ISSN (online): 2414-3030 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Evelyn O’Callaghan (Editor in Chief) Michael A. Bucknor (Senior Editor) Lisa Outar (Senior Editor) Glyne Griffith Rachel L. Mordecai Kevin Adonis Browne BOOK REVIEW EDITOR Antonia MacDonald EDITORIAL BOARD Edward Baugh Victor Chang Alison Donnell Mark McWatt Maureen Warner-Lewis EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Laurence A. Breiner Rhonda Cobham-Sander Daniel Coleman Anne Collett Raphael Dalleo Denise deCaires Narain Curdella Forbes Aaron Kamugisha Geraldine Skeete Faith Smith Emily Taylor THE JOURNAL OF WEST INDIAN LITERATURE has been published twice-yearly by the Departments of Literatures in English of the University of the West Indies since October 1986. JWIL originated at the same time as the first annual conference on West Indian Literature, the brainchild of Edward Baugh, Mervyn Morris and Mark McWatt. It reflects the continued commitment of those who followed their lead to provide a forum in the region for the dissemination and discussion of our literary culture. -

Echoes of an African Drum: the Lost Literary Journalism of 1950S South Africa

DRUM 7 Writer/philosopher Can Themba, 1952. Photo by Jürgen Schadeberg, www.jurgenshadeberg.com. Themba studied at Fort Hare University and then moved to the Johannesburg suburb of Sophiatown. He joined the staff of Drum magazine after winning a short-story competition and quickly became the most admired of all Drum writers. 8 Literary Journalism Studies, Vol. 8, No. 1, Spring 2016 The Drum office, 1954. Photo by Jürgen Schadeberg, www.jurgenshadeberg.com. The overcrowded Johannesburg office housed most of Drum’s journalists and photographers. Schadeberg took the picture while Anthony Sampson directed it, showing (from left to right) Henry Nxumalo, Casey Motsitsi, Ezekiel Mphalele, Can Themba, Jerry Ntsipe, Arthur Maimane (wearing hat, drooping cigerette), Kenneth Mtetwa (on floor), Victor Xashimba, Dan Chocho (with hat), Benson Dyanti (with stick) and Robert Gosani (right with camera). Todd Matshikiza was away. 9 Echoes of an African Drum: The Lost Literary Journalism of 1950s South Africa Lesley Cowling University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa (or Johannesburg) Abstract: In post-apartheid South Africa, the 1950s era has been romanti- cized through posters, photographs, a feature film, and television commer- cials. Much of the visual iconography and the stories come from the pages of Drum, a black readership magazine that became the largest circulation publication in South Africa, and reached readers in many other parts of the continent. Despite the visibility of the magazine as a cultural icon and an extensive scholarly literature on Drum of the 1950s, the lively journalism of the magazine’s writers is unfamiliar to most South Africans. Writers rather than journalists, the early Drum generation employed writing strategies and literary tactics that drew from popular fiction rather than from reporterly or literary essay styles. -

Golden Man Booker Prize Shortlist Celebrating Five Decades of the Finest Fiction

Press release Under embargo until 6.30pm, Saturday 26 May 2018 Golden Man Booker Prize shortlist Celebrating five decades of the finest fiction www.themanbookerprize.com| #ManBooker50 The shortlist for the Golden Man Booker Prize was announced today (Saturday 26 May) during a reception at the Hay Festival. This special one-off award for Man Booker Prize’s 50th anniversary celebrations will crown the best work of fiction from the last five decades of the prize. All 51 previous winners were considered by a panel of five specially appointed judges, each of whom was asked to read the winning novels from one decade of the prize’s history. We can now reveal that that the ‘Golden Five’ – the books thought to have best stood the test of time – are: In a Free State by V. S. Naipaul; Moon Tiger by Penelope Lively; The English Patient by Michael Ondaatje; Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel; and Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders. Judge Year Title Author Country Publisher of win Robert 1971 In a Free V. S. Naipaul UK Picador McCrum State Lemn Sissay 1987 Moon Penelope Lively UK Penguin Tiger Kamila 1992 The Michael Canada Bloomsbury Shamsie English Ondaatje Patient Simon Mayo 2009 Wolf Hall Hilary Mantel UK Fourth Estate Hollie 2017 Lincoln George USA Bloomsbury McNish in the Saunders Bardo Key dates 26 May to 25 June Readers are now invited to have their say on which book is their favourite from this shortlist. The month-long public vote on the Man Booker Prize website will close on 25 June. -

Diane Ackerman Amy Adams Geraldine Brooks Billy Collins Mark Doty Matt Gallagher Jack Gantos Smith5th Hendersonannual Alice Hoffman Marlon James T

Diane Ackerman Amy Adams Geraldine Brooks Billy Collins Mark Doty Matt Gallagher Jack Gantos Smith5th HendersonAnnual Alice Hoffman Marlon James T. Geronimo Johnson Sebastian Junger Ann Leary Anthony Marra Richard Michelson Valzhyna Mort Michael Patrick O’Neill Evan Osnos Nathaniel Philbrick Diane Rehm Michael Ruhlman Emma Sky Richard Michelson NANTUCKET, MA June 17 - 19, 2016 Welcome In marking our fifth year of the Nantucket Book Festival, we are thrilled with where we have come and where we are set to go. What began as an adventurous idea to celebrate the written word on Nantucket has grown exponentially to become a gathering of some of the most dynamic writers and speakers in the world. The island has a rich literary tradition, and we are proud that the Nantucket Book Festival is championing this cultural imperative for the next generation of writers and readers. Look no further than the Book Festival’s PEN Faulkner Writers in Schools program or our Young Writer Award to see the seeds of the festival bearing fruit. Most recently, we’ve added a visiting author program to our schools, reaffirming to our students that though they may live on an island, there is truly no limit to their imaginations. Like any good story, the Nantucket Book Festival hopes to keep you intrigued, inspired, and engaged. This is a community endeavor, dedicated to enriching the lives of everyone who attends. We are grateful for all of your support and cannot wait to share with you the next chapter in this exciting story. With profound thanks, The Nantucket Book Festival Team Mary Bergman · Meghan Blair-Valero · Dick Burns · Annye Camara Rebecca Chapa · Rob Cocuzzo · Tharon Dunn · Marsha Egan Jack Fritsch · Josh Gray · Mary Haft · Maddie Hjulstrom Wendy Hudson · Amy Jenness · Bee Shay · Ryder Ziebarth Table of Contents Book Signing ......................1 Weekend at a Glance ..........16-17 Schedules: Friday ................2-3 Map of Events .................18-19 Saturday ............ -

AIR-46-1-Digital.Pdf

AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL REVIEW VOLUME 46 No. 1 JANUARY 2021 AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL & JEWISH AFFAIRS COUNCIL IRRECONCILABLE DIFFERENCES Israel likely heading for yet another election just as the Biden administration takes over in Washington UNRWA’S TURNING POINT? MARRAKECH UNFORGETTABLE COLD PEACE, EXPRESS LESSONS WARM PEACE A unique opportunity to reform Israel’s historic nor- Innovative new How the UAE normalisa- the controversial UN agency for malisation deal with Holocaust education tion differs from Israel’s Palestinian refugees ....................... PAGE 30 Morocco ........PAGE 20 programs in longstanding peace with Australia ........PAGE 25 Egypt .................PAGE 6 NAME OF SECTION WITH COMPLIMENTS AND BEST WISHES FROM GANDEL GROUP CHADSTONE SHOPPING CENTRE 1341 DANDENONG ROAD CHADSTONE VIC 3148 TEL: (03) 8564 1222 FAX: (03) 8564 1333 With Compliments from P O BOX 400 SOUTH MELBOURNE, 3205, AUSTRALIA TELEPHONE: (03) 9695 8700 2 AIR – January 2021 AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL VOLUME 46 No. 1 REVIEW JANUARY 2021 EDITOR’S NOTE NAME OF SECTION his month’s AIR edition focuses on Israel’s apparent drift toward new elections – the ON THE COVER Tfourth in two years – just as the Biden administration takes office in the US. Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Amotz Asa-El explains the events that look very likely to lead to Israeli voters going Netanyahu (R) and alternate-PM back to the polls in March, while Israeli pundit Haviv Rettig Gur looks at recent devel- and Defence Minister Benny opments that may make long-serving Israeli PM Binyamin Netanyahu more vulnerable Gantz attend the weekly cabinet this time around. In addition, American columnist Jonathan Tobin argues the upcoming meeting in Jerusalem on June inauguration of Joe Biden makes a new Israeli poll sensible, while, in the editorial, Colin 21, 2020. -

INTRODUCTION 1. Though the Policies of Apartheid and Separate Development Sought to Preserve African Languages and Traditions, T

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. Though the policies of apartheid and separate development sought to preserve African languages and traditions, this was part of a wider programme to confine the 'Bantu' to their tribal cultures; it took no account of the degree of tribal integration that had taken place, and very little account of the natural linguistic developments within the black communities- developments which were never towards greater purity. The major liberation movements therefore view this official tampering with African cultures as part of the machinery of repression. 2. Recent work by Couzens and others demonstrates much more fully than has hitherto been shown, the operations of African tradition within the work of those early writers. See Daniel Kunene's new translation of Mofolo's Chaka and Tim Couzens' editions ofDhlomo. 3. A shebeen is a drinking place run, illegally, by African women, usually in their own homes. Thus while it serves the function of a bar, and is often the scene of wild drinking bouts, it has the character of a family living room. 4. See R. Kavanagh, Theatre and Cultural Struggle in South Africa (London: Zed Books, 1985) p. 33. CHAPTER 1 1. Mafika Gwala, No More Lullabies (Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1982) p. 10. 2. Terry Eagleton, Literary Theory: An Introduction (Oxford: Basil Black well, 1983) p. 21. 3. Athol Fugard, John Kani & Winston Ntshona, 'The Island', Statements (London & Capetown: Oxford U.P., 1974) p. 62. 4. Eagleton, Criticism and Ideology: A Study in Marxist Literary Theory (London: Verso, 1978) p. 49. 5. Donald Woods, Biko (New York & London: Paddington Press, 1978) p. -

Canongate JULY–DECEMBER 2017 the Graybar Hotel CURTIS DAWKINS

Canongate JULY–DECEMBER 2017 The Graybar Hotel CURTIS DAWKINS A gritty, unflinching and deeply moving collection of stories by a debut writer currently serving a life sentence in Michigan’s prison system. His stories form a vivid portrait of prison life, painted from behind bars The Graybar Hotel offers a glimpse into the reality of prison life through the eyes of the people who spend their days and years behind bars. A man sits collect-calling strangers every day just to hear the sounds of the outside world; an inmate recalls his descent into addiction as his prison softball team gears up for an annual tournament; a prisoner is released and finds freedom more complex and baffling than he expected. In this stunning debut story collection, Curtis Dawkins, who is currently serving a life sentence without parole, gives voice to RELEASE DATE: 6 JULY 2017 the experience of some of the most isolated members of our HARDBACK society. 9781786891112 £14.99 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Curtis Dawkins grew up in rural Illinois and earned an MFA in fiction writing at Western Michigan University. He has struggled with alcohol and substance abuse through most of his life and, during a botched robbery, killed a man on Halloween 2004. Since late 2005, he’s been serving a life sentence, with no possibility of parole, in various prisons throughout Michigan. He has three children with his partner, Kim, who is a writing professor living in Portland, Oregon. Canongate July–December 2017 02 Under The Skin MICHEL FABER One of Michel Faber’s best-loved novels, this is an utterly compulsive and mysterious masterpiece With an introduction by David Mitchell Isserley spends most of her time driving. -

This Bookshelf: 2020 Books Links to All Steve Hopkins' Bookshelves

This Bookshelf: 2020 Books Links to All Steve Hopkins’ Bookshelves Web Page PDF/epub/Searchable Link to Latest Book Reviews: Book Reviews Blog Links to Current Bookshelf: Pending and Read 2020 Books 2020 Books Links to 549 Books Read or Skipped in 2020 2020 Bookshelf 2020 Bookshelf Links to All Books from 1999 All Books Authors A through All Books Authors A through through 2020 Authors A-G G G Links to All Books from 1999 through 2020 Authors H-M All Books Authors H All Books Authors H through M through M Links to All Books from 1999 All Books Authors N through All Books Authors N through through 2020 Authors N-Z Z Z Book of Books: An ebook of Book of Books books read, reviewed or skipped from 1999 through 2020 This web page lists all 360 books reviewed by Steve Hopkins at http://bkrev.blogspot.com during 2020 as well as 189 books relegated to the Shelf of Ennui. You can click on the title of a book or on the picture of any jacket cover to jump to amazon.com where you can purchase a copy of any book on this shelf. Key to Ratings: I love it ***** I like it **** It’s OK *** I don’t like it ** I hate it * Click on Title (Click on Link Blog Picture to to purchase at Author(s) Rating Comments Date Purchase at amazon.com) amazon.com Endless. For an immersive mediation on war, read Salar Abdoh’s novel titled, Out of Mesopotamia. From the perspective of protagonist Saleh, a journalist, we struggle to make sense of those who are engaged in what Out of seems like endless war.