Image, Meta-Text and Text in Byzantium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 S. Constantinou and M. Meyer

INDEX A Agatha, saint, 151n10, 152n19 Abduction of Europa, 192, 193, 198, Agora, 299, 300 206, 208, 210, 211, 233n15. See Akropolites, George: Historia, 111, also Zeus 131n6 Achilles, 201, 206, 215, 216, 221, Alexandria, 37, 114, 145, 148 229, 238n84 Alexios I Komnenos, 85, 291, 293, Achilles Tatius: Leucippe and 295, 297–301, 314n73 Clitophon, 184n18, 184n22, Allegory, 19, 191, 221, 241n117 187n49, 217, 239n90, 243n148 Ambrose of Milan, 120, 136n42 Adam, 121, 191, 229, 230, 248, 250, Anastasia the Younger, saint, 6 264n14. See also Eve Andronikos I Komnenos, 170, 185n32 Adonis, 207, 221, 226–228, 241n124, Andronikos, saint, 16, 36–47, 50, 57, 243n153 58, 289 Adoption, 103, 104 Anemas, Michael, 299, 301 Adrianos, saint, 16, 36, 38, 47–58, Anger (orgē), 3, 4, 7, 9, 13, 81, 82, 59n5 87, 111–113, 115, 116, 119, Affect, 3, 6, 8, 9, 11, 25n32, 95, 102. 120, 123–130, 131n10, 138n61, See also Emotion; Mood; Pathos 138n66, 139n71, 165, 167, Affection (affectionate love; agapē; 184n28, 246, 258, 260, 287, 297 philia;storgē), 8, 11, 36, 37, 40, Animals 49, 52, 54, 57, 159–162, 164, horse, 193, 221, 225–228 165, 170, 175, 176, 285, 286. hound, 194, 221 See also Love lion/lioness, 193, 206, 218, 221, Agapetos: Ekthesis, 112, 125, 131n8, 225, 236n59 138n62, 138n64, 308n16 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2019 317 S. Constantinou and M. Meyer (eds.), Emotions and Gender in Byzantine Culture, New Approaches to Byzantine History and Culture, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96038-8 318 INDEX seahorse (hippocamp), 192, 211, B 214, 215, 240n114 Bacchanal revelry, 214 stag, 194, 221 ‘Barbarism’ in art, 246, 254, 257, 258, Anna Komnene: Alexiad, 4, 16, 20, 260, 261, 263n8 22n12, 58, 66, 67, 80–88, 288, Basil I, 111, 269n44 291–305 Basil II, 141, 142, 312n46 Antioch, 37, 46, 114, 122, 230 Basileus, 115, 127. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-40589-9 - Byzantine Style, Religion and Civilization: In Honour of Sir Steven Runciman Elizabeth Jeffreys Index More information Index Aaron 11, 13 Apion I, Flavius 419 Abbas Hierax, and Apion family 419, 422 Apion II, Flavius 418–19 Abgar of Edessa 192, 193 Apion III, Flavius 418, 420, 422–3 letter (in Constantinople) 198–9 Apion IV, Flavius 420–1 Acre, crusader scriptorium 165, 167 Apion papyri 419, 421; see also Oxyrhynchus Acta Davidis, Symeonis et Georgii 362, 364, and evidence for administration of 365 estates 421 chronology for pardon of and evidence for family involvement 421–2 Theophilos 366–70 architecture, military, Crusader and quality of as source 363–4 Byzantine 159–62 Symeon’s role in 366, 367, 368, 369 ark of the covenant 9, 14 Aetios, papias 182 armed pilgrimage 253–4 Agat‘angelos, ‘History of Armenia’ 185–6 and knights as small group leaders 253 Agios Ioannis, alternative names for 43 garrisons to guard communications 259–60 port of 41–3 Armenian traditions in 9th cent. routes from 44 Constantinople 186, 187 Alan princess, a hostage 150 Askalon, fortress and shrine 261–2 Alexander, emperor 341, 344 Asotˇ Bagratuni 181, 182, 209, 218 Alexios I Komnenos, letter to Robert of Attaleiates, Michael 244 Flanders 253, 260, 261 Attaleiates, Michael, Diataxis of 244–6; see also on armed pilgrimage 254 Monastery of the Hospice of Al-Idrisi, and Gulf of Dyers 58 All-Merciful Christ Alisan,ˇ L. M., and ‘Discovery of the Relics of the Holy Illuminator’ 177 B. L., Egerton 1139 165–7, 168 Amphilochia, date of first part 210 ‘Basilios’ 166 date of whole work 211 and Jerusalem 165 nature of 209, 210–11 miniatures 166 of Photios painters 166 real addressee of? 211–12 Queen Melisende’s Psalter? 165, 167 so-called, of Basil of Caesarea 212 Bagrat, son of king of Georgia 150 sources used 213–14 Bajezid I 74, 75, 76, 78 theology of 209–10 Balfour, A. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-43093-7 - Byzantium in the Iconoclast Era c. 680–850: A History Leslie Brubaker and John Haldon Index More information Index Given the centrality of these concepts to the present work, the terms ‘iconoclasm, iconoclast’ etc., and ‘iconophile’ are not indexed. Monuments are normally listed under location. ‘Abbas, son of al-Ma’mun 409 Anatolikon 28, 70–1, 74, 159, 292, 294, 358, ‘Abd al-Malik, caliph 778 362, 364, 386, 410, 549, 553, 554, 586, ‘Abd ar-Rahman II, caliph 411 613, 633, 634, 691, 697, 704, 759 Abu Qurra, Theodore 188, 233, 234, 246 Anchialos 288, 290 acheiropoieta 35–6, 38, 55, 56, 774, 782 Andrew of Crete 20, 70, 80, 85, 90, 151, 643 Adamnan 58, 141, 781 Angelidi, Christine 216 Adata 410 angels, images of 776 adiectio sterilium 718, 720 Ankara 255, 289, 409, 540, 549, 552, 553, 561 Adoptionism 283, 309 Anna, patrikia 313, 424, 446 Adrianople 361, 362 Anna, daughter of Theodora and Theophilos Aetios, protospatharios 288, 292, 294, 637 433 Agathias 13, 54, 478, 776, 777 Annales Bertiniani 516 Agatho, pope 20 Anne, wife of Leo III 144 Agathos, monastery of 316, 424 Anthony, bishop of Syllaion 369, 390, 391, Agauroi, monastery of 397 392 Aghlabids 405, 411 Anthony the Younger, Life 735 Aistulf, king 169 Anthousa of Mantineon, monastery of 216, Akathistos, Synaxarion 93 240 Akroinon 76, 546, 553 anthypatos 593, 671, 673, 682, 712–13, 716, Alakilise, Church of the Archangel Gabriel 742, 764, 769–70 416 Antidion, monastery 425 Alcuin 281 Antioch (Pisidia) 75 Alexander, Paul 373, 375 Antoninus of -

Part One of Book, Pp1-66 (PDF File, 1.82

GREECE BOOKS AND WRITERS This publication has been sponsored By the Hellenic Cultural Heritage S.A., the organising body of the Cultural Olympiad. PUBLICATION COMMITTEE VANGELIS HADJIVASSILIOU STEFANOS KAKLAMANIS ELISABETH KOTZIA STAVROS PETSOPOULOS ELISABETH TSIRIMOKOU YORYIS YATROMANOLAKIS Sourcing of illustrations SANDRA VRETTA Translations JOHN DAVIS (sections I-III), ALEXANDRA KAPSALI (sections IV-V) JANE ASSIMAKOPOULOS (sections VI-VII) ANNE-MARIE STANTON-IFE (introductory texts, captions) Textual editing JOHN LEATHAM Secretariat LENIA THEOPHILI Design, selection of illustrations and supervision of production STAVROS PETSOPOULOS ISBN 960 - 7894 - 29 - 4 © 2001, MINISTRY OF CULTURE - NATIONAL BOOK CENTRE OF GREECE 4 Athanasiou Diakou St, 117 42 Athens, Greece Tel.: (301) 92 00 300 - Fax: (301) 92 00 305 http://www.books.culture.gr e-mail:[email protected] GREECE BOOKS AND WRITERS NATIONAL BOOK CENTRE OF GREECE MINISTRY OF CULTURE GREECE - BOOKS AND WRITERS – SECTION I Cardinal BESSARION (black and white engraving 17 X 13 cm. National Historical Museum, Athens) The most celebrated of the Greek scholars who worked in Italy was Cardinal BESSARION (1403-1472). An enthusiastic supporter of the union of the Eastern and Western Churches, he worked tirelessly to bring about the political and cultural conditions that would allow this to take place. He made a major contribution to the flowering of humanist studies in Italy and played a key role in gathering and preserving the ancient Greek, Byzantine and Latin cultural heritage By systematically collecting and copying manuscripts of rare literary and artistic value, frequently at great personal expense and sacrifice and with the help of various Greek refugee scholars and copyists (Conati autem sumus, quantum in nobis fuit, non tam multos quam optimos libros colligere, et sin- gulorum operum singula volumina, sicque cuncta fere sapien- tium graecorum opera, praesertim quae rara errant et inventu dif- ficilia, coegimus). -

1St ONLINE EDINBURGH BYZANTINE BOOK FESTIVAL

1st ONLINE EDINBURGH BYZANTINE BOOK FESTIVAL 5-7 February 2021 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful to the various publishers for agreeing to list their books and providing special discounts to the attendees of the 1st Online Edinburgh Byzantine Book Festival. Petros Bouras-Vallianatos Edinburgh 11 January 2021 BOOKLET LISTING PUBLISHERS’ CATALOGUES ALEXANDROS PRESS ALEXANDROS PRESS Dobbedreef 25, NL-2331 SW Leiden, The Netherlands Tel. + 31 71 576 11 18 No fax: + 31 71 572 75 17 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.alexandrospress.com VAT number NL209186367B02 Dutch Chamber of Commerce registration number: 28088681 ING Bank, Amsterdam, Acc. no. 5219443 BIC: INGBNL2A IBAN: NL89INGB0005219443 Please, find below the books of Alexandros Press, all of them with a discount of approximately 65-75%. The price of the books is € 60-90 for individuals, instead of € 250, plus postage and handling and, for EU counties, 9% VAT. This price is valid only if directly ordered from Alexandros Press, not through (and for) booksellers. Please, send a copy to the Library with 50% discount € 125 instead of 250, if directly ordered from Alexandros Press. See also the Antiquarian books at the end of this message, including Spatharakis’ Portrait, in the case you or you library may need them, but without discount. You can order by sending an e-mail to [email protected] You can pay with American Express card, PayPal mentioning [email protected] or (by preference) to the above written ING Bank, Amsterdam. About the quality of the books: “Soulignons pour finir la qualité de l’édition et la richesse de l’illustration, avec ses nombreuses images en couleur dont les éditions Alexandros Press se sont fait une spécialité et dont on ne dira jamais assez l’importance pour les historiens d’art.” Catherine Jolivet- Lévy, Revue des Etudes Byzantines, 66 (2008), 304-307. -

Urs Peschlow, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz

EARLY CHRISTIAN & BYZANTINE ART, ARCHITECTURE & ARCHAEOLOGY The Library of Prof. Dr. Urs Peschlow, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz 2,416 titles in circa 2,750 volumes Urs Peschlow Urs Peschlow (* 11. März 1943 in Hannover) ist ein deutscher Christlicher Archäologe und byzantinischer Kunsthistoriker . Urs Peschlow studierte von 1962 bis 1970 Kunstgeschichte , Klassische Archäologie und Christliche Archäologie an der Universität Marburg , der Universität Thessaloniki und der Universität Mainz . Die Promotion erfolgte 1970 mit einer Arbeit zum Thema Die Irenenkirche in Istanbul in Mainz. Daran schloss sich 1970/71 ein Werkvertrag an der Abteilung Rom des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts , 1971 wurde er Referent der Außenstelle Abteilung Istanbul des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts . 1975 bis 1979 war Peschlow Stipendiat der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft in Istanbul, 1979/80 Forschungsstipendiat in Dumbarton Oaks , Washington. 1981 wurde er Wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter beziehungsweise Hochschulassistent an der Universität Göttingen . Von 1985 bis 2008 lehrte Peschlow als C 3-Professur am Institut für Kunstgeschichte der Universität Mainz. Er war mit der Klassischen Archäologin Anneliese Peschlow verheiratet und ist korrespondierendes Mitglied des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts . Schriften • Die Irenenkirche in Istanbul. Untersuchungen zur Architektur , Wasmuth, Tübingen 1977 ( Istanbuler Mitteilungen , Beiheft 18) ISBN 3-8030-1717-3 • mit Friedrich Wilhelm Deichmann : Zwei spätantike Ruinenstätten in Nordmesopotamien , C. H. Beck, München 1977 (Sitzungsberichte der bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften 1977 H. 2) ISBN 3-7696-1483-6 • mit Friedrich Wilhelm Deichmann, Joachim Kramer: Corpus der Kapitelle der Kirche von San Marco zu Venedig , Wiesbaden 1981 (Forschungen zur Kunstgeschichte und Christlichen Archäologie, Bd. 12) • Hrsg. mit Otto Feld: Studien zur spätantiken und byzantinischen Kunst. Friedrich Wilhelm Deichmann gewidmet (3 Bände), Habelt, Bonn 1986 (Monographien des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums Bd. -

John of Damascus and the Consolidation of Classical Christian Demonology

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Dissertations (1934 -) Projects Imagining Demons in Post-Byzantine Jerusalem: John of Damascus and the Consolidation of Classical Christian Demonology Nathaniel Ogden Kidd Marquette University Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Kidd, Nathaniel Ogden, "Imagining Demons in Post-Byzantine Jerusalem: John of Damascus and the Consolidation of Classical Christian Demonology" (2018). Dissertations (1934 -). 839. https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/839 IMAGINING DEMONS IN POST-BYZANTINE JERUSALEM: JOHN OF DAMASCUS AND THE CONSOLIDATION OF CLASSICAL CHRISTIAN DEMONOLOGY by The Rev. Nathaniel Ogden Kidd, B.A., M.Div A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin December, 2018 ABSTRACT IMAGINING DEMONS IN POST-BYZANTINE JERUSALEM: JOHN OF DAMASCUS AND THE CONSOLIDATION OF CLASSICAL CHRISTIAN DEMONOLOGY The Rev. Nathaniel Ogden Kidd, B.A., M.Div Marquette University, 2018 This dissertation traces the consolidation of a classical Christian framework for demonology in the theological corpus of John of Damascus (c. 675 – c. 750), an eighth century Greek theologian writing in Jerusalem. When the Damascene sat down to write, I argue, there was a great variety of demonological options available to him, both in the depth of the Christian tradition, and in the ambient local imagination. John’s genius lies first in what he chose not to include, but second in his ability to synthesize a minimalistic demonology out of a complex body of material and integrate it into a broader theological system. -

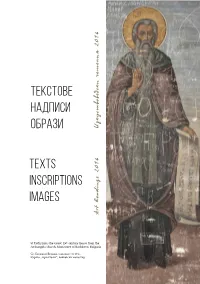

Текстове Надписи Образи Texts Inscriptions Images

ТЕКСТОВЕ НАДПИСИ ОБРАЗИ Изкуствоведски четения 2016 TEXTS INSCRIPTIONS IMAGES Art Readings 2016 St Euthymius the Great, 19th century fresco from the Archangels church, Monastery of Bachkovo, Bulgaria Св. Евтимий Велики, стенопис от 19 в., църква „Архангели“, Бачковски манастир ИЗКУСТВОВЕДСКИ ЧЕТЕНИЯ Тематично годишно рецензирано издание за изкуствознание в два тома ART READINGS Thematic annual peer-reviewed edition in Art Studies in two volumes Международна редакционна колегия International Advisory Board Andrea Babuin (Italy) Konstantinos Giakoumis (Albania) Nenad Makulijevic (Serbia) Vincent Debiais (France) Редактори от ИИИзк In-house Editorial Board Ivanka Gergova Emmanuel Moutafov Научни редактори на тома Scholarly Edited by Emmanuel Moutafov Jelena Erdeljan (Serbia) Institute of Art Studies 21 Krakra Str. 1504 Sofia Bulgaria www.artstudies.bg © Институт за изследване на изкуствата, БАН, 2017 ИЗКУСТВОВЕДСКИ ЧЕТЕНИЯ Тематично годишно рецензирано издание за изкуствознание в два тома 2016/ т. I – Старо изкуство ТЕКСТОВЕ • НАДПИСИ • ОБРАЗИ TEXTS • INSCRIPTIONS •IMAGES ART READINGS Thematic annual peеr-reviewed edition in Art Studies in two volumes 2016/ vol. I – Old Art Под научната редакция на Емануел Мутафов Йелена Ерделян Scholarly edited by Emmanuel Moutafov Jelena Erdeljan София 2017 Книгата се издава със съдействието на Плесио компютърс Content Art Readings 2016 ............................................................................................................11 Emmanuel Moutafov The Visual Language of Roman Art and Roman -

Alchemy and Exegesis from Antioch to Constantinople, 11Th Century By

Matter Redeemed: Alchemy and Exegesis from Antioch to Constantinople, 11th century by Alexandre Mattos Roberts A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Maria Mavroudi, Chair Professor Susanna Elm Professor Asad Ahmed Professor Michael Cooperson Spring 2015 © 2015 by Alexandre M. Roberts Abstract Matter Redeemed: Alchemy and Exegesis from Antioch to Constantinople, 11th century by Alexandre Mattos Roberts Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Maria Mavroudi, Chair This dissertation examines how scholars in eleventh-century Constantinople and Antioch (un- der Byzantine rule, 969-1084) understood matter and its transformation. It argues that matter, a concept inherited from ancient philosophy, continued to be a fertile and malleable idea-complex endowed with cultural and religious meaning in medieval thought-worlds of the Eastern Mediter- ranean. The first three chapters form a case study on the unpublished Arabic translations oflatean- tique Christian texts by the 11th-century Byzantine Orthodox deacon ʿAbdallāh ibn al-Faḍl of An- tioch (fl. c.1052). They proceed by increasing specificity: chapter 1 surveys Ibn al-Faḍl’s Greek- to-Arabic translations; chapter 2 turns to one of these translations, of a famous and highly influ- ential commentary on the first chapter of the Book of Genesis by Basil of Caesarea (c.330–?379), his Homilies on the Hexaemeron; and chapter 3 reads Ibn al-Faḍl’s marginalia to his translation of Basil’s Hexaemeron. Together, they provide insight into a culturally Byzantine milieu in which the primary language of communication was Arabic, exploring how intellectuals in that context understood matter, where this understanding came from, and why it resonated in this cityatthe edge of the empire. -

Andreas Rhoby: Der Byzantinische Literaturhorizont

Online-Handbuch zur Geschichte Südosteuropas Andreas Rhoby Der byzantinische Literaturhorizont. Griechische Literatur vom 4. bis zum 15. Jahrhundert und ihr Kontext aus dem Band: Sprache und Kultur in Südosteuropa bis 1800 2 Inhalt 1. Einleitung 2. Die frühen Jahrhunderte. Die Anfänge der byzantinischen Literatur 3. Die Zeit des Übergangs: von Kaiser Herakleios bis zum Ende des Ikonoklasmus 3.1 Von der ersten Hälfte des 7. Jahrhunderts bis zum Beginn des Ikonoklasmus 3.2 Die Epoche des Ikonoklasmus 4. Die Blütezeit unter den Makedonenkaisern 5. Das 11. Jahrhundert: politische Krise, kulturelle Blüte 6. Das Zeitalter der Komnenen: literarische Blüte im „langen“ 12. Jahrhundert (1081–1204) 7. Das 13. Jahrhundert: byzantinische Literatur im Exil 8. Von der byzantinischen Restauration bis zum Niedergang: Literatur in der Palaiologenzeit 9. Rückblick und Ausblick Zitierempfehlung und Nutzungsbedingungen für diesen Artikel / Recommended Citation and Terms of Use Der byzantinische Literaturhorizont. Griechische Literatur vom 4. bis zum 15. Jahrhundert — 3 Der byzantinische Literaturhorizont. Griechische Literatur vom 4. bis zum 15. Jahrhundert und ihr Kontext 1. Einleitung Die byzantinische Literatur verfügte lange Zeit über eine ausgesprochen schlechte Presse. Sie war insbesondere hinsichtlich ihrer rhetorischen Texte Urteilen wie „Nichtigkeit weltlicher Rhetorik, rhetorische Scheinwissenschaft“, „Entleerung und Erstarrung“ oder „Rhetorik war in Byzanz in Mode, und eine Menge impotenter Literaten diente dieser Mode und ritt das Genos zuschanden“ -

Theologizing Or Indulging Desire: Bathers in the Sacra Parallela (Paris, Bnf, Gr

Theologizing or Indulging Desire: Bathers in the Sacra Parallela (Paris, BnF, gr. 923)* Mati Meyer The Sacra Parallela is a theological and ascetic florilegium of biblical (OT and NT) and patristic citations related to a now-lost model entitled Hiera, composed in Palestine by John of Damascus (ca. 675 – ca. 749). The only known copy is a ninth-century manuscript (Paris, BnF, gr. 923) thought to have been produced in a Greek monastery in Italy, possibly in Rome.1 The text contains three treatises— one on God and the Trinity, another on man, and a third on vices and virtues. The scriptural and exegetical citations are arranged in alphabetical order by στοιχεῖα (alphabetical letters) and τίτλοι (titles). The manuscript, lavishly decorated with miniatures executed in a schematized style, represents a defined group of scenes depicting male and female bathers, which, modeled after Graeco-Roman formulae, have never been discussed in light of their value for gender studies.2 I contend that the images of bathers, though limited in number, reveal a larger tableau wherein the canonical sensuous naked body of the female undergoes construction and deconstruction. In an attempt to discuss the nature and scope of these images, I will rely on the concepts of the “male gaze” and Meyer – Theologizing or Indulging Desire “visual pleasure” as formulated by cinema critic Laura Mulvey,3 as well as the notion of “third gender” developed, for instance, in Gilbert Herdt’s study as a theoretical tool in the study of gender.4 The “female” thereby transcends traditional gender boundaries and is no longer portrayed as a fixed perception. -

Honey Culture in Byzantium an Outline of /Textual, Iconographic

SOPHIA GERMANIDOU 93 HONEY CULTURE IN BYZANTIUM AN OUTLINE OF TEXTUAL, ICONOGRAPHIC AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE Sophia Germanidou Archaeologist, 26th Ephorate of Byzantine Antiquities, Greece [email protected] Apiculture is a stockbreeding activity of and Early Byzantine pottery in Greece, Athens 2013. diachronic and intercultural importance, as it covers As a result, beehives met attention and currently are a basic human need, the consumption of sweet food, increasingly exhibited in their capacity as cultural a need as old as human existence itself. Nevertheless, objects, especially in Athens (i.e. Syntagma metro the process followed for the production, the use of station, Airport museum). beekeeping products and primarily, the multifaceted expressions of these activities in the art, archaeology, The insect and its products met extensive literary intellectual and material culture of the Byzantine uses. They appear frequently as paradigms in the era, have not been closely documented. The present theological works of saint Basil the Great, bishop of paper attempts to fill this gap, focusing on information Caesarea, whose text of the Hexaemeron (The Six Days pertaining to three main fields, namely the various of Creation) created an extensive tradition2. Commonly textual, artistic and archaeological sources. used schemes by Fathers of the Orthodox Church include the contrast between physical weakness and A limited interest in this realm of study was mental strength, the comparison of the divine dicta already demonstrated in the time of Aristotle and, to sweeter than honey, the attribution of the insect as later on, by the Roman agricultural authorship industrious and diligent. Moreover, references in the (Varro, Virgil, Columella, Pliny the Elder, Pappus of Lives of Saints not only provide useful information Alexandria, Palladius1).