NUAULU Setflement and ECOLOGY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Workpapers in Indonesian Languages and Cultures

( J WORKPAPERS IN INDONESIAN LANGUAGES AND CULTURES VOLUME 6 - MALUKU ,. PATTIMURA UNIVERSITY and THE SUMMER INSTITUTE OP LINGUISTICS in cooperation with THE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION AND CULTURE WORKPAPERS IN INDONESIAN LANGUAGES AND CULTURES VOLUME 6 - MALUKU Nyn D. Laidig, Edi tor PAT'I'IMORA tJlflVERSITY and THE SUMMER IRSTlTUTK OP LIRGOISTICS in cooperation with 'l'BB DBPAR".l'MElI'1' 01' BDUCATIOII ARD CULTURE Workpapers in Indonesian Languages and cultures Volume 6 Maluku Wyn D. Laidig, Editor Printed 1989 Ambon, Maluku, Indonesia Copies of this publication may be obtained from Summer Institute of Linguistics Kotak Pos 51 Ambon, Maluku 97001 Indonesia Microfiche copies of this and other publications of the Summer Institute of Linguistics may be obtained from Academic Book Center Summer Institute of Linguistics 7500 West Camp Wisdom Road l Dallas, TX 75236 U.S.A. ii PRAKATA Dengan mengucap syukur kepada Tuhan yang Masa Esa, kami menyambut dengan gembira penerbitan buku Workpapers in Indonesian Languages , and Cultures. Penerbitan ini menunjukkan adanya suatu kerjasama yang baik antara Universitas Pattimura deng~n Summer Institute of Linguistics; Maluku . Buku ini merupakan wujud nyata peran serta para anggota SIL dalam membantu masyarakat umumnya dan masyarakat pedesaan khususnya Diharapkan dengan terbitnya buku ini akan dapat membantu masyarakat khususnya di pedesaan, dalam meningkatkan pengetahuan dan prestasi mereka sesuai dengan bidang mereka masing-masing. Dengan adanya penerbitan ini, kiranya dapat merangsang munculnya penulis-penulis yang lain yang dapat menyumbangkan pengetahuannya yang berguna bagi kita dan generasi-generasi yang akan datang. Kami ucapkan ' terima kasih kepada para anggota SIL yang telah berupaya sehingga bisa diterbitkannya buku ini Akhir kat a kami ucapkan selamat membaca kepada masyarakat yang mau memiliki buku ini. -

Fault Systems of the Eastern Indonesian Triple Junction: Evaluation of Quaternary Activity and Implications for Seismic Hazards

Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ at Duke University on December 24, 2016 Fault systems of the eastern Indonesian triple junction: evaluation of Quaternary activity and implications for seismic hazards IAN M. WATKINSON* & ROBERT HALL SE Asia Research Group, Department of Earth Sciences, Royal Holloway University of London, Egham, Surrey TW20 0EX, UK *Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Eastern Indonesia is the site of intense deformation related to convergence between Australia, Eurasia, the Pacific and the Philippine Sea Plate. Our analysis of the tectonic geomor- phology, drainage patterns, exhumed faults and historical seismicity in this region has highlighted faults that have been active during the Quaternary (Pleistocene to present day), even if instrumental records suggest that some are presently inactive. Of the 27 largely onshore fault systems studied, 11 showed evidence of a maximal tectonic rate and a further five showed evidence of rapid tectonic activity. Three faults indicating a slow to minimal tectonic rate nonetheless showed indications of Quaternary activity and may simply have long interseismic periods. Although most studied fault systems are highly segmented, many are linked by narrow (,3 km) step-overs to form one or more long, quasi-continuous segment capable of producing M . 7.5 earthquakes. Sinistral shear across the soft-linked Yapen and Tarera–Aiduna faults and their continuation into the transpres- sive Seram fold–thrust belt represents perhaps the most active belt of deformation and hence the greatest seismic hazard in the region. However, the Palu–Koro Fault, which is long, straight and capable of generating super-shear ruptures, is considered to represent the greatest seismic risk of all the faults evaluated in this region in view of important strike-slip strands that appear to traverse the thick Quaternary basin-fill below Palu city. -

Fault Systems of the Eastern Indonesian Triple Junction: Evaluation of Quaternary Activity and Implications for Seismic Hazards

Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ at Royal Holloway, University of London on May 1, 2017 Fault systems of the eastern Indonesian triple junction: evaluation of Quaternary activity and implications for seismic hazards IAN M. WATKINSON* & ROBERT HALL SE Asia Research Group, Department of Earth Sciences, Royal Holloway University of London, Egham, Surrey TW20 0EX, UK *Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Eastern Indonesia is the site of intense deformation related to convergence between Australia, Eurasia, the Pacific and the Philippine Sea Plate. Our analysis of the tectonic geomor- phology, drainage patterns, exhumed faults and historical seismicity in this region has highlighted faults that have been active during the Quaternary (Pleistocene to present day), even if instrumental records suggest that some are presently inactive. Of the 27 largely onshore fault systems studied, 11 showed evidence of a maximal tectonic rate and a further five showed evidence of rapid tectonic activity. Three faults indicating a slow to minimal tectonic rate nonetheless showed indications of Quaternary activity and may simply have long interseismic periods. Although most studied fault systems are highly segmented, many are linked by narrow (,3 km) step-overs to form one or more long, quasi-continuous segment capable of producing M . 7.5 earthquakes. Sinistral shear across the soft-linked Yapen and Tarera–Aiduna faults and their continuation into the transpres- sive Seram fold–thrust belt represents perhaps the most active belt of deformation and hence the greatest seismic hazard in the region. However, the Palu–Koro Fault, which is long, straight and capable of generating super-shear ruptures, is considered to represent the greatest seismic risk of all the faults evaluated in this region in view of important strike-slip strands that appear to traverse the thick Quaternary basin-fill below Palu city. -

Languages of Indonesia (Maluku)

Ethnologue report for Indonesia (Maluku) Page 1 of 30 Languages of Indonesia (Maluku) See language map. Indonesia (Maluku). 2,549,454 (2000 census). Information mainly from K. Whinnom 1956; K. Polman 1981; J. Collins 1983; C. and B. D. Grimes 1983; B. D. Grimes 1994; C. Grimes 1995, 2000; E. Travis 1986; R. Bolton 1989, 1990; P. Taylor 1991; M. Taber 1993. The number of languages listed for Indonesia (Maluku) is 132. Of those, 129 are living languages and 3 are extinct. Living languages Alune [alp] 17,243 (2000 WCD). 5 villages in Seram Barat District, and 22 villages in Kairatu and Taniwel districts, west Seram, central Maluku. 27 villages total. Alternate names: Sapalewa, Patasiwa Alfoeren. Dialects: Kairatu, Central West Alune (Niniari-Piru-Riring-Lumoli), South Alune (Rambatu-Manussa-Rumberu), North Coastal Alune (Nikulkan-Murnaten-Wakolo), Central East Alune (Buriah-Weth-Laturake). Rambatu dialect is reported to be prestigious. Kawe may be a dialect. Related to Nakaela and Lisabata-Nuniali. Lexical similarity 77% to 91% among dialects, 64% with Lisabata-Nuniali, 63% with Hulung and Naka'ela. Classification: Austronesian, Malayo-Polynesian, Central- Eastern, Central Malayo-Polynesian, Central Maluku, East, Seram, Nunusaku, Three Rivers, Amalumute, Northwest Seram, Ulat Inai More information. Amahai [amq] 50 (1987 SIL). Central Maluku, southwest Seram, 4 villages near Masohi. Alternate names: Amahei. Dialects: Makariki, Rutah, Soahuku. Language cluster with Iha and Kaibobo. Also related to Elpaputih and Nusa Laut. Lexical similarity 87% between the villages of Makariki and Rutah; probably two languages, 59% to 69% with Saparua, 59% with Kamarian, 58% with Kaibobo, 52% with Piru, Luhu, and Hulung, 50% with Alune, 49% with Naka'ela, 47% with Lisabata-Nuniali and South Wemale, 45% with North Wemale and Nuaulu, 44% with Buano and Saleman. -

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for All People Groups & LR-Upgs of Asia-Pacific

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & Least-Reached-UPGs of Asia-Pacific AGWM ed. Source: Joshua Project data, www.joshuaproject.net I give credit & thanks to Asia Harvest & Create International for permission to use their people group photos. 2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & LR-UPGs of Asia-Pacific (China = separate region & DPG) ASIA-PACIFIC SUMMARY: 3,523 total PG; 830 FR & LR-UPG = Frontier & Least Reached-Unreached People Groups Downloaded from www.joshuaproject.net = August, 2020 LR-UPG defin: less than 2% Evangelical & less than 5% total Christian Frontier (FR) definition: 0% to 0.1% Christian Why pray--God loves lost: world UPGs = 7,407; Frontier = 5,042. Color code: green = begin new area; blue = begin new country "Prayer is not the only thing we can can do, but it is the most important thing we can do!" Luke 10:2, Jesus told them, "The harvest is plentiful, but the workers are few. Ask the Lord of the harvest, therefore, to send out workers into his harvest field." Let's dream God's dreams, and fulfill God's visions -- God dreams of all people groups knowing & loving Him! Revelation 7:9, "After this I looked and there before me was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language, standing before the throne and in front of the Lamb." Why Should We Pray For Unreached People Groups? * Missions & salvation of all people is God's plan, God's will, God's heart, God's dream, Gen. 3:15! * In the Great Commissions Jesus commands us to reach all peoples in the world, Matt. -

0=AFRICAN Geosector

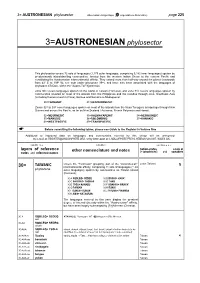

3= AUSTRONESIAN phylosector Observatoire Linguistique Linguasphere Observatory page 225 3=AUSTRONESIAN phylosector édition princeps foundation edition DU RÉPERTOIRE DE LA LINGUASPHÈRE 1999-2000 THE LINGUASPHERE REGISTER 1999-2000 publiée en ligne et mise à jour dès novembre 2012 published online & updated from November 2012 This phylosector covers 72 sets of languages (1,179 outer languages, comprising 3,182 inner languages) spoken by predominantly island-dwelling communities, located from the western Indian Ocean to the eastern Pacific and constituting the Austronesian intercontinental affinity. They extend more than half-way around the planet (eastwards from 43º E to 109º W; see note under phylozone 39=), and have also been associated with the languages of phylozone 47=Daic, within the "Austro-Tai" hypothesis. Zone 30= covers languages spoken on the island of Taiwan (Formosa), and zone 31= covers languages spoken by communities situated on most of the islands from the Philippines and the Celebes through Java, Southeast Asia (including Hainan island in China), Borneo and Sumatra to Madagascar: 30=TAIWANIC 31=HESPERONESIC Zones 32= to 39= cover languages spoken on most of the islands from the Nusa Tenggera archipelago through New Guinea and across the Pacific, as far as New Zealand / Aotearoa, French Polynesia and Hawaii: 32=MESONESIC 33=HALMAYAPENIC 34=NEOGUINEIC 35=MANUSIC 36=SOLOMONIC 37=KANAKIC 38=WESTPACIFIC 39=TRANSPACIFIC Before consulting the following tables, please see Guide to the Register in Volume One Les données supplémentaires -

3=AUSTRONESIAN Phylosector

3= AUSTRONESIAN phylosector Observatoire Linguistique Linguasphere Observatory page 225 3=AUSTRONESIAN phylosector This phylosector covers 72 sets of languages (1,179 outer languages, comprising 3,182 inner languages) spoken by predominantly island-dwelling communities, located from the western Indian Ocean to the eastern Pacific and constituting the Austronesian intercontinental affinity. They extend more than half-way around the planet (eastwards from 43º E to 109º W; see note under phylozone 39=), and have also been associated with the languages of phylozone 47=Daic, within the "Austro-Tai" hypothesis. Zone 30= covers languages spoken on the island of Taiwan (Formosa), and zone 31= covers languages spoken by communities situated on most of the islands from the Philippines and the Celebes through Java, Southeast Asia (including Hainan island in China), Borneo and Sumatra to Madagascar: 30=TAIWANIC 31=HESPERONESIC Zones 32= to 39= cover languages spoken on most of the islands from the Nusa Tenggera archipelago through New Guinea and across the Pacific, as far as New Zealand / Aotearoa, French Polynesia and Hawaii: 32=MESONESIC 33=HALMAYAPENIC 34=NEOGUINEIC 35=MANUSIC 36=SOLOMONIC 37=KANAKIC 38=WESTPACIFIC 39=TRANSPACIFIC ☛ Before consulting the following tables, please see Guide to the Register in Volume One Additional or improved data on languages and communities covered by this sector will be welcomed by e-mail at: [email protected], or by letter-post at: LINGUASPHERE PRESS, HEBRON SA34 0XT, WALES (UK). COLUMN 1 & 2 COLUMN 3 -

Uhm Phd 9107027 R.Pdf

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copysubmitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adverselyaffect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrightmaterial had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sectionswith small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. U-M-I University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. M148106-1346 USA 313;761-4700 8001521-0600 Order Number 9107027 Language shift: Changing patterns of language allegiance in western Seram Florey, Margaret Jean, Ph.D. University of Hawaii, 1990 U-M-I 300 N. -

Workpapers in Indonesian Languages and Cultures

( J WORKPAPERS IN INDONESIAN LANGUAGES AND CULTURES VOLUME 6 - MALUKU ,. PATTIMURA UNIVERSITY and THE SUMMER INSTITUTE OP LINGUISTICS in cooperation with THE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION AND CULTURE WORKPAPERS IN INDONESIAN LANGUAGES AND CULTURES VOLUME 6 - MALUKU Nyn D. Laidig, Edi tor PAT'I'IMORA tJlflVERSITY and THE SUMMER IRSTlTUTK OP LIRGOISTICS in cooperation with 'l'BB DBPAR".l'MElI'1' 01' BDUCATIOII ARD CULTURE Workpapers in Indonesian Languages and cultures Volume 6 Maluku Wyn D. Laidig, Editor Printed 1989 Ambon, Maluku, Indonesia Copies of this publication may be obtained from Summer Institute of Linguistics Kotak Pos 51 Ambon, Maluku 97001 Indonesia Microfiche copies of this and other publications of the Summer Institute of Linguistics may be obtained from Academic Book Center Summer Institute of Linguistics 7500 West Camp Wisdom Road l Dallas, TX 75236 U.S.A. ii PRAKATA Dengan mengucap syukur kepada Tuhan yang Masa Esa, kami menyambut dengan gembira penerbitan buku Workpapers in Indonesian Languages , and Cultures. Penerbitan ini menunjukkan adanya suatu kerjasama yang baik antara Universitas Pattimura deng~n Summer Institute of Linguistics; Maluku . Buku ini merupakan wujud nyata peran serta para anggota SIL dalam membantu masyarakat umumnya dan masyarakat pedesaan khususnya Diharapkan dengan terbitnya buku ini akan dapat membantu masyarakat khususnya di pedesaan, dalam meningkatkan pengetahuan dan prestasi mereka sesuai dengan bidang mereka masing-masing. Dengan adanya penerbitan ini, kiranya dapat merangsang munculnya penulis-penulis yang lain yang dapat menyumbangkan pengetahuannya yang berguna bagi kita dan generasi-generasi yang akan datang. Kami ucapkan ' terima kasih kepada para anggota SIL yang telah berupaya sehingga bisa diterbitkannya buku ini Akhir kat a kami ucapkan selamat membaca kepada masyarakat yang mau memiliki buku ini. -

The Biology of the Moluccan Megapode Eulipoa Wallacei (Aves, Galliformes, Megapodiidae) on Haruku and Other Moluccan Islands; Part 2: final Report

C.J. Heij1, C.F.E. Rompas2 & C.W. Moeliker1 1 Natuurhistorisch Museum Rotterdam 2 Bogor Agricultural Institute* The biology of the Moluccan megapode Eulipoa wallacei (Aves, Galliformes, Megapodiidae) on Haruku and other Moluccan Islands; part 2: final report Heij, C.J., Rompas, C.F .E., & Moeliker, C.W., 1997 - The biology of the Moluccan megapode Eulipoa wallacei (Aves, Galliformes, Megapodiidae) on Haruku and other Moluccan Islands; part 2: final report - DEINSEA 3: 1-123 [ISSN 0923-9308]. Published 9 October 1997. The Moluccan megapode Eulipoa wallacei inhabits forests of several Moluccan Islands (Indonesia). The birds only leave this habitat for the purpose of egg-laying in self-dug burrows on sandy beaches, where solar heat incubates the eggs. The eggs are collected, sold and consumed by local people, a tradition that is said to threaten the species’ existence. An intensive study was carried out in the periods June 1994 - June 1995 and January - May 1996 at one of the largest known communal nesting grounds, ‘Tanjung Maleo’ near Kailolo Village on Haruku Island and at nesting grounds on other islands. In close collaboration with the local people, reproduction data were obtained by daily counts of the number of collected eggs and fledged chicks. Experiments were carried out to establish the incubation period. Egg-laying behaviour was studied with nightvision equipment. The egg-laying interval, home range, inland habitat and provenance of the female birds were established by radio-tracking of nine individuals. Of the 36.263 eggs that were harvested in the 94/95 season (1 April-31 March) peak numbers (max. -

Personal Names, Lexical Replacement, and Language Shift in Eastern Indonesia

CAKALELE, VOL. 8 (1997): 27–58 Margaret Florey & Rosemary Bolton Personal Names, Lexical Replacement, and Language Shift in Eastern Indonesia MARGARET J. FLOREY LA TROBE UNIVERSITY ROSEMARY A. BOLTON SUMMER INSTITUTE OF LINGUISTICS FULLER THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY 1. Introduction In Central Maluku, a pronounced association has been noted between patterns of language use and religious affiliation. In Christian villages, a considerable number of indigenous languages have become extinct, and language shift towards the regional lingua franca, Ambonese Malay, is endangering the majority of the remaining languages.1 Indigenous lan- guages in Muslim villages are also undergoing language shift. Although the process is slower and use of indigenous languages is apparent among all generations of speakers, there is a perceptible narrowing of the func- tions of the languages. Very few groups in Maluku have resisted con- version from their ancestral religion to Christianity or Islam. However, the villages in which ancestral religious practices have been retained are marked by language maintenance and greater retention of traditional ritual practices. The vast majority of the Nuaulu of south central Seram in eastern Indonesia have retained their ancestral religion. In contrast, only one of the 26 Alune villages (located in west Seram) has not converted to Christianity.2 This study presents a comparative analysis of naming practices between these two Austronesian language groups. The analysis 1Cf. Collins (1982, 1983), Florey (1990, 1991, 1993), Grimes (1991). 2Collins (pers. comm.) notes that Kawa, located on the north coast of Seram, is an Alune village that has been subject to very intensive in-migration of people from Sulawesi. -

Eksplorasi Geoarkeologi Situs Paleolitik Di Pulau

EKSPLORASI GEOARKEOLOGI SITUS PALEOLITIK DI PULAU SERAM, PROVINSI MALUKU (Geoarchaeological Exploration of Paleolitical Sites on The Island of Seram, Moluccas Province) Muh. Fadhlan S. Intan Pusat Penelitian Arkeologi Nasional. Jl. Raya Condet Pejaten No. 4 Jakarta Selatan 12510, e-mail: [email protected] INFO ARTIKEL ABSTRACT Histori artikel East Seram District, Central Maluku, and West Seram regency is located on the island of Seram, where research was conducted, save a lot of Diterima: 31 Maret 2017 cultural, one of the paleolithic period, which is a long time not received Direvisi: 3 Mei 2017 attention from environmental researchers. It is used as the basis of the Disetujui:12 Juni 2017 main issues that include geology in general. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to perform surface geological mapping in general as one of the efforts to provide geological information, while the goal is to determine aspects of geomorphology, stratigraphy, structural geology associated with Keywords: the existence of paleolithic sites in the study area. The research method geology, begins with a literature review, surveys, analysis, and interpretation of field data. Environmental scanning provides information about the landscape pleistocene, consists of plains morphological units, units of corrugated morphology paleolithic, weak, strong corrugated morphology unit, and units of karst morphology. open site, The river berstadia old-mature river stadium, periodical/permanent river, and river episodic/intermittent river. Constituent rock is sandstone, lithic tools materials limestone, marl, andesite, tuff, schist, volcanic breccias, reef limestones, conglomerates, and alluvial. Geological structures such as faults and folds. Ceram Research discovered 14 Paleolithic sites. From the analysis Kata kunci: of petrology, lithic tools made of jasper rocks, chert, metalimestone, flint, geologi, and quartzite.