The Origins of Anglo-Saxon Kingship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saxon Newsletter-Template.Indd

Saxon Newsletter of the Sutton Hoo Society No. 50 / January 2010 (© Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery) Hoards of Gold! The recovery of hundreds of 7th–8th century objects from a field in Staffordshire filled the newspapers when it was announced by the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) at a press conference on 24 September. Uncannily, the first piece of gold was recovered seventy years to the day after the first gold artefact was uncovered at Sutton Hoo on 21 July 1939.‘The old gods are speaking again,’ said Dr Kevin Leahy. Dr Leahy, who is national finds advisor on early medieval metalwork to the PAS and who catalogued the hoard, will be speaking to the SHS on 29 May (details, back page). Current Archaeology took the hoard to mark the who hate thee be driven from thy face’. (So even launch of their ‘new look’ when they ran ten pages this had a military flavour). of pictures in their November issue [CA 236] — “The art is like Sutton Hoo — gold with clois- which, incidentally, includes a two-page interview onée garnet and fabulous ‘Style 2’ animal interlace with our research director, Professor Martin on pommels and cheek guards — but maybe a Carver. bit later in date. This and the inscription suggest Martin tells us, “The hoard consists of 1,344 an early 8th century date overall — but this will items mainly of gold and silver, although 864 of probably move about. More than six hundred pho- these weigh less than 3g. The recognisable parts of tos of the objects can be seen on the PAS’s Flickr the hoard are dominated by military equipment — website. -

First Evidence of Farming Appears; Stone Axes, Antler Combs, Pottery in Common Use

BC c.5000 - Neolithic (new stone age) Period begins; first evidence of farming appears; stone axes, antler combs, pottery in common use. c.4000 - Construction of the "Sweet Track" (named for its discoverer, Ray Sweet) begun; many similar raised, wooden walkways were constructed at this time providing a way to traverse the low, boggy, swampy areas in the Somerset Levels, near Glastonbury; earliest-known camps or communities appear (ie. Hembury, Devon). c.3500-3000 - First appearance of long barrows and chambered tombs; at Hambledon Hill (Dorset), the primitive burial rite known as "corpse exposure" was practiced, wherein bodies were left in the open air to decompose or be consumed by animals and birds. c.3000-2500 - Castlerigg Stone Circle (Cumbria), one of Britain's earliest and most beautiful, begun; Pentre Ifan (Dyfed), a classic example of a chambered tomb, constructed; Bryn Celli Ddu (Anglesey), known as the "mound in the dark grove," begun, one of the finest examples of a "passage grave." c.2500 - Bronze Age begins; multi-chambered tombs in use (ie. West Kennet Long Barrow) first appearance of henge "monuments;" construction begun on Silbury Hill, Europe's largest prehistoric, man-made hill (132 ft); "Beaker Folk," identified by the pottery beakers (along with other objects) found in their single burial sites. c.2500-1500 - Most stone circles in British Isles erected during this period; pupose of the circles is uncertain, although most experts speculate that they had either astronomical or ritual uses. c.2300 - Construction begun on Britain's largest stone circle at Avebury. c.2000 - Metal objects are widely manufactured in England about this time, first from copper, then with arsenic and tin added; woven cloth appears in Britain, evidenced by findings of pins and cloth fasteners in graves; construction begun on Stonehenge's inner ring of bluestones. -

Medieval Weapons: an Illustrated History of Their Impact

MEDIEVAL WEAPONS Other Titles in ABC-CLIO’s WEAPONS AND WARFARE SERIES Aircraft Carriers, Paul E. Fontenoy Ancient Weapons, James T. Chambers Artillery, Jeff Kinard Ballistic Missiles, Kev Darling Battleships, Stanley Sandler Cruisers and Battle Cruisers, Eric W. Osborne Destroyers, Eric W. Osborne Helicopters, Stanley S. McGowen Machine Guns, James H. Willbanks Military Aircraft in the Jet Age, Justin D. Murphy Military Aircraft, 1919–1945, Justin D. Murphy Military Aircraft, Origins to 1918, Justin D. Murphy Pistols, Jeff Kinard Rifles, David Westwood Submarines, Paul E. Fontenoy Tanks, Spencer C. Tucker MEDIEVAL WEAPONS AN ILLUSTRATED HISTORY OF THEIR IMPACT Kelly DeVries Robert D. Smith Santa Barbara, California • Denver, Colorado • Oxford, England Copyright 2007 by ABC-CLIO, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data DeVries, Kelly, 1956– Medieval weapons : an illustrated history of their impact / Kelly DeVries and Robert D. Smith. p. cm. — (Weapons and warfare series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-10: 1-85109-526-8 (hard copy : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-85109-531-4 (ebook) ISBN-13: 978-1-85109-526-1 (hard copy : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-1-85109-531-5 (ebook) 1. Military weapons—Europe—History—To 1500. 2. Military art and science—Europe—History—Medieval, 500-1500. I. Smith, Robert D. (Robert Douglas), 1954– II. -

An Analysis of the Metal Finds from the Ninth-Century Metalworking

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-2017 An Analysis of the Metal Finds from the Ninth-Century Metalworking Site at Bamburgh Castle in the Context of Ferrous and Non-Ferrous Metalworking in Middle- and Late-Saxon England Julie Polcrack Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Polcrack, Julie, "An Analysis of the Metal Finds from the Ninth-Century Metalworking Site at Bamburgh Castle in the Context of Ferrous and Non-Ferrous Metalworking in Middle- and Late-Saxon England" (2017). Master's Theses. 1510. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/1510 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ANALYSIS OF THE METAL FINDS FROM THE NINTH-CENTURY METALWORKING SITE AT BAMBURGH CASTLE IN THE CONTEXT OF FERROUS AND NON-FERROUS METALWORKING IN MIDDLE- AND LATE-SAXON ENGLAND by Julie Polcrack A thesis submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The Medieval Institute Western Michigan University August 2017 Thesis Committee: Jana Schulman, Ph.D., Chair Robert Berkhofer, Ph.D. Graeme Young, B.Sc. AN ANALYSIS OF THE METAL FINDS FROM THE NINTH-CENTURY METALWORKING SITE AT BAMBURGH CASTLE IN THE CONTEXT OF FERROUS AND NON-FERROUS METALWORKING IN MIDDLE- AND LATE-SAXON ENGLAND Julie Polcrack, M.A. -

Complete Dissertation

University of Groningen The growth of an Austrasian identity Stegeman, Hans IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2014 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Stegeman, H. (2014). The growth of an Austrasian identity: Processes of identification and legend construction in the Northeast of the Regnum Francorum, 600-800. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 02-10-2021 The growth of an Austrasian identity Processes of identification and legend construction in the Northeast of the Regnum Francorum, 600-800 Proefschrift ter verkrijging van het doctoraat aan de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen op gezag van de rector magnificus dr. -

The Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Mercia and the Origins and Distribution of Common Fields*

The Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Mercia and the origins and distribution of common fields* by Susan Oosthuizen Abstract: This paper aims to explore the hypothesis that the agricultural layouts and organisation that had de- veloped into common fields by the high middle ages may have had their origins in the ‘long’ eighth century, between about 670 and 840 AD. It begins by reiterating the distinction between medieval open and common fields, and the problems that inhibit current explanations for their period of origin and distribution. The distribution of common fields is reviewed and the coincidence with the kingdom of Mercia noted. Evidence pointing towards an earlier date for the origin of fields is reviewed. Current views of Mercia in the ‘long’ eighth century are discussed and it is shown that the kingdom had both the cultural and economic vitality to implement far-reaching landscape organisation. The proposition that early forms of these field systems may have originated in the ‘long’ eighth century is considered, and the paper concludes with suggestions for further research. Open and common fields (a specialised form of open field) endured in the English landscape for over a thousand years and their physical remains still survive in many places. A great deal is known and understood about their distribution and physical appearance, about their man- agement from their peak in the thirteenth century through the changes of the later medieval and early modern periods, and about how and when they disappeared. Their origins, however, present a continuing problem partly, at least, because of the difficulties in extrapolating in- formation about such beginnings from documentary sources and upstanding earthworks that record – or fossilise – mature or even late field systems. -

Constructing Early Anglo-Saxon Identity in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles

Chapter 7 Constructing Early Anglo-Saxon Identity in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles Courtnay Konshuh The chronicle compiled at King Alfred’s court after 891 was part of his educa- tional reform and was also part of an attempt to create a common national identity for the English. This can be seen in the contemporary annals (i.e. from 871 to 891), but the large body of annals drawn together from diverse sources for the preceding nine centuries shows this same focus. The earlier annals, while not necessarily compiled at the same time, were selected and manipu- lated with the same goals, and are organised thematically into annals which explore Britannia’s roots as a Roman colony, its development as a Christian nation, and the adventus of the Germanic tribes. Barbara Yorke has shown some of these accounts to be semi-historical or mythological, but they are jux- taposed with historically accurate descriptions. While the early annals have a different compilation context than those which document Alfred’s reign, they were nonetheless selected, organised and inflated in order to legitimise the line of Cerdic and bestow authority on Alfred as well as his descendants. In this, they follow the same model as later annals in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles.1 In light of recent research, it seems well established that the compilation of the “Common Stock” or “Alfredian Chronicle” (i.e. the annals to 891 common to most Anglo-Saxon Chronicles) was a courtly endeavour and that the exemplar for the earliest A-manuscript was a product of King Alfred’s scholarly circle.2 While Alfred’s personal involvement in this may not have been particularly large,3 the political thought of his circle of scholars can be detected throughout the annals. -

Constructing the Seventh Century

COLLÈGE DE FRANCE – CNRS CENTRE DE RECHERCHE D’HISTOIRE ET CIVILISATION DE BYZANCE TRAVAUX ET MÉMOIRES 17 constructing the seventh century edited by Constantin Zuckerman Ouvrage publié avec le concours de la fondation Ebersolt du Collège de France et de l’université Paris-Sorbonne Association des Amis du Centre d’Histoire et Civilisation de Byzance 52, rue du Cardinal-Lemoine – 75005 Paris 2013 PREFACE by Constantin Zuckerman The title of this volume could be misleading. “Constructing the 7th century” by no means implies an intellectual construction. It should rather recall the image of a construction site with its scaffolding and piles of bricks, and with its plentiful uncovered pits. As on the building site of a medieval cathedral, every worker lays his pavement or polishes up his column knowing that one day a majestic edifice will rise and that it will be as accomplished and solid as is the least element of its structure. The reader can imagine the edifice as he reads through the articles collected under this cover, but in this age when syntheses abound it was not the editor’s aim to develop another one. The contributions to the volume are regrouped in five sections, some more united than the others. The first section is the most tightly knit presenting the results of a collaborative project coordinated by Vincent Déroche. It explores the different versions of a “many shaped” polemical treatise (Dialogica polymorpha antiiudaica) preserved—and edited here—in Greek and Slavonic. Anti-Jewish polemics flourished in the seventh century for a reason. In the centuries-long debate opposing the “New” and the “Old” Israel, the latter’s rejection by God was grounded in an irrefutable empirical proof: God had expelled the “Old” Israel from its promised land and given it to the “New.” In the first half of the seventh century, however, this reasoning was shattered, first by the Persian conquest of the Holy Land, which could be viewed as a passing trial, and then by the Arab conquest, which appeared to last. -

How Could Phenological Records from the Chinese Poems of the Tang and Song Dynasties

https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-2020-122 Preprint. Discussion started: 28 September 2020 c Author(s) 2020. CC BY 4.0 License. How could phenological records from the Chinese poems of the Tang and Song Dynasties (618-1260 AD) be reliable evidence of past climate changes? Yachen Liu1, Xiuqi Fang2, Junhu Dai3, Huanjiong Wang3, Zexing Tao3 5 1School of Biological and Environmental Engineering, Xi’an University, Xi’an, 710065, China 2Faculty of Geographical Science, Key Laboratory of Environment Change and Natural Disaster MOE, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, 100875, China 3Key Laboratory of Land Surface Pattern and Simulation, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Science (CAS), Beijing, 100101, China 10 Correspondence to: Zexing Tao ([email protected]) Abstract. Phenological records in historical documents have been proved to be of unique value for reconstructing past climate changes. As a literary genre, poetry reached its peak period in the Tang and Song Dynasties (618-1260 AD) in China, which could provide abundant phenological records in this period when lacking phenological observations. However, the reliability of phenological records from 15 poems as well as their processing methods remains to be comprehensively summarized and discussed. In this paper, after introducing the certainties and uncertainties of phenological information in poems, the key processing steps and methods for deriving phenological records from poems and using them in past climate change studies were discussed: -

MEDIEVAL DAMASCUS Arabic Book Culture, Library Culture and Reading Culture Is Significantly Enriched.’ Li Guo, University of Notre Dame and MEDIEVAL

PLURALITY KONRAD HIRSCHLER ‘This is a tour de force of ferocious codex dissection, relentless bibliographical probing and imaginative reconstructive storytelling. Our knowledge of medieval MEDIEVAL DAMASCUS DAMASCUS MEDIEVAL Arabic book culture, library culture and reading culture is significantly enriched.’ Li Guo, University of Notre Dame AND MEDIEVAL The first documented insight into the content and DIVERSITY structure of a large-scale medieval Arabic library The written text was a pervasive feature of cultural practices in the medieval Middle East. At the heart of book circulation stood libraries that experienced a rapid expansion from the DAMASCUS twelfth century onwards. While the existence of these libraries is well known, our knowledge of their content and structure has been very limited as hardly any medieval Arabic catalogues have been preserved. This book discusses the largest and earliest medieval library of the PLURALITY AND Middle East for which we have documentation – the Ashrafiya library in the very centre of IN AN Damascus – and edits its catalogue. The catalogue shows that even book collections attached to Sunni religious institutions could hold very diverse titles, including Muʿtazilite theology, DIVERSITY IN AN Shiʿite prayers, medical handbooks, manuals for traders, stories from the 1001 Nights and texts extolling wine consumption. ARABIC LIBRARY ARABIC LIBRARY Listing over two thousand books the Ashrafiya catalogue is essential reading for anybody interested in the cultural and intellectual history of Arabic societies. -

Vespasia Polla Vespasiani Family*

Vespasia Polla Vespasiani Family* Titus Flavius Petronius Sabinus c45 BCE Centurion Reserve Army Vespasius Pollo of Pompeii, Tax Collector Reate Sabinia Italy-15 Rome [+] Tertulia Military Tribune ?-45 Tertuilius di Roma 32 BCE Lazio Italy -9AD Rome Nursia + ? = Titus Flavius I Sabinus Tax Collector + = Vespasia & Banker c20 BCE Rieti Lazio Italy-? Polla 19 BCE-? = Flavius = Titus Flavius Caesar Vespasianus Augustus 9 Falacrinae-79 Rieti, Italy Proconsul = Titus Flavius II Sabinus Consul of Rome c8-69 Vespasia c10 of Africa 53-69, Emperor of Rome 69-79 + 1. 38 AD Domitilla the Elder 2 Sabratha + 1. 63 AD Arrechina Clementina Arrechinus 1 BCE-c10BCE North Africa (present Libya)-66 Rome; +[2.] Antonia Caenis ?-74 = 3 children Tertulla c12-65; +2. Marcia Furnilla Petillius Rufus, Prefect of Rome c 18 AD + ? Caesia = 1. Titus Flavius Caesar = 1. Titus Flavius Caesar Domitianus Augustus = 1. Flavia = Quintus Petillius Cerialis Vespasianus Augustus 39 51-96 Rome Emperor of Rome 81-96 + 1. 70 Domitilla the Caesius Rufus Caesii Senator Rome-81 Rieti Emperor of Domitia Longina; [+] 2. Julia Flavia 64-91 Rome Younger 45- of Rome, Governor of Britain Rome 79-81 +1. Marcia 66 Rome +60 30 Ombrie Italy-83 Furnilla+ 2. Arrecina Tertulla Cassius Labienus Posthumus = 1. Titus Flavius [PII265-270] + ? = + =Flavia Saint + = Titus Flavius III Caesar 73-82 Rome = 1. Julia Flavia 64-91 Domitilla ?-95< Clemens Sabinus 50-95 Rome = Marcus Postumia Festus de Afranius Hannibalianus Rome, Consul Suffect de Rome ?- Afranii Prince of Syria c200- = Titus Flavius IV -

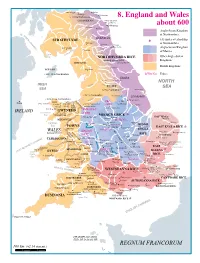

The Demo Version

Æbucurnig Dynbær Edinburgh Coldingham c. 638 to Northumbria 8. England and Wales GODODDIN HOLY ISLAND Lindisfarne Tuidi Bebbanburg about 600 Old Melrose Ad Gefring Anglo-Saxon Kingdom NORTH CHANNEL of Northumbria BERNICIA STRATHCLYDE 633 under overlordship Buthcæster Corebricg Gyruum * of Northumbria æt Rægeheafde Mote of Mark Tyne Anglo-Saxon Kingdom Caerluel of Mercia Wear Luce Solway Firth Bay NORTHHYMBRA RICE Other Anglo-Saxon united about 604 Kingdoms Streonæshalch RHEGED Tese Cetreht British kingdoms MANAW Hefresham c 624–33 to Northumbria Rye MYRCNA Tribes DEIRA Ilecliue Eoforwic NORTH IRISH Aire Rippel ELMET Ouse SEA SEA 627 to Northumbria æt Bearwe Humbre c 627 to Northumbria Trent Ouestræfeld LINDESEGE c 624–33 to Northumbria TEGEINGL Gæignesburh Rhuddlan Mærse PEC- c 600 Dublin MÔN HOLY ISLAND Llanfaes Deganwy c 627 to Northumbria SÆTE to Mercia Lindcylene RHOS Saint Legaceaster Bangor Asaph Cair Segeint to Badecarnwiellon GWYNEDD WREOCAN- IRELAND Caernarvon SÆTE Bay DUNODING MIERCNA RICE Rapendun The Wash c 700 to Mercia * Usa NORTHFOLC Byrtun Elmham MEIRIONNYDD MYRCNA Northwic Cardigan Rochecestre Liccidfeld Stanford Walle TOMSÆTE MIDDIL Bay POWYS Medeshamstede Tamoworthig Ligoraceaster EAST ENGLA RICE Sæfern PENCERSÆTE WATLING STREET ENGLA * WALES MAGON- Theodford Llanbadarn Fawr GWERTH-MAELIENYDD Dommoceaster (?) RYNION RICE SÆTE Huntandun SUTHFOLC Hamtun c 656 to Mercia Beodericsworth CEREDIGION Weogornaceaster Bedanford Grantanbrycg BUELLT ELFAEL HECANAS Persore Tovecestre Headleage Rendlæsham Eofeshamm + Hereford c 600 GipeswicSutton Hoo EUIAS Wincelcumb to Mercia EAST PEBIDIOG ERGING Buccingahamm Sture mutha Saint Davids BRYCHEINIOG Gleawanceaster HWICCE Heorotford SEAXNA SAINT GEORGE’SSaint CHANNEL DYFED 577 to Wessex Ægelesburg * Brides GWENT 628 to Mercia Wæclingaceaster Hetfelle RICE Ythancæstir Llanddowror Waltham Bay Cirenceaster Dorchecestre GLYWYSING Caerwent Wealingaford WÆCLINGAS c.