Note to User

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Pond to Pro: Hockey As a Symbol of Canadian National Identity

From Pond to Pro: Hockey as a Symbol of Canadian National Identity by Alison Bell, B.A. A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology and Anthropology Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario 19 April, 2007 © copyright 2007 Alison Bell Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliotheque et Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-26936-7 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-26936-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce,Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve,sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform,et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Blue Banner, Is Published Two Times Per Year

bbllue banner HAEL’S COLLEGE SC ST. MIC HOOL The LEGACYIssue Volume 15 ~ Fall/Winter 2013 Inducted: Murray Costello ’53 Graduated: Consiglio Di Nino ’13 Recognized: Michael J. McDonald ’54 lettersbb tol theu editore banner HAEL’S COLLEGE S ST. MIC CHOOL The St. Michael’s College School alumni magazine, Blue Banner, is published two times per year. It reflects the history, accomplishments and stories of graduates and its purpose is to promote collegiality, respect and Christian values under the direction of the Basilian Fathers. PRESIDENT: Terence M. Sheridan ’89 CONTACT DIRECTORY EDITOR: Gavin Davidson ’93 St. Michael’s College School: www.stmichaelscollegeschool.com CO-EDITOR: Michael De Pellegrin ’94 Blue Banner Online: www.mybluebanner.com ONLINE STORE NOW OPEN! shop.stmichaelscollegeschool.com CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Basilian Fathers: www.basilian.org Kimberley Bailey, Jillian Kaster, Fr. Malo ’66, Pat CISAA (Varsity Athletic Schedule): www.cisaa.ca Dianne Levine - Manager Mancuso ’90, Harold Moffat ’52, Marc Montemurro ’93, Twitter: www.twitter.com/smcs1852 Shanna Lacroix - Co-Manager Rick Naranowicz ’73, Joe Younder ’56, Fabiano Micoli ’84, Advancement Office: [email protected] Stephanie Nicholls, Steve Pozgaj ’71 Alumni Affairs: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS Archives Office: [email protected] Blue Banner Feedback: [email protected] Message from the President 2 Communications Office: [email protected] Alumni Association Message 3 You helped us get here... Tel: 416-653-3180 ext. 292 Editor’s Letter 4 Fax: 416-653-8789 Letters to the Editor 5 E-mail: [email protected] Around St. Mike’s 6 • Admissions (ext. 195) Men of St. Michael’s: Michael McDonald ’55 8 • Advancement (ext. -

By-Laws • Regulations • History Effective 2018-2019 Season

By-Laws • Regulations • History Effective 2018-2019 Season HockeyCanada.ca As adopted at Ottawa, December 4, 1914 and amended to May 2018. HOCKEY CANADA BY-L AWS REGULATIONS HISTORY As amended to May 2018 This edition is prepared for easy and convenient reference only. Should errors occur, the contents of this book will be interpreted by the President according to the official minutes of meetings of Hockey Canada. The Playing Rules of Hockey Canada are published in a separate booklet and may be obtained from the Executive Director of any Hockey Canada Member, from any office of Hockey Canada or from Hockey Canada’s web site. HockeyCanada.ca 1 HOCKEY CANADA MISSION STATEMENT Lead, Develop and Promote Positive Hockey Experiences Joe Drago 1283 Montrose Avenue Sudbury, ON P3A 3B9 Chair of the Board Hockey Canada 2018-19 2 HockeyCanada.ca CHAIR’S MESSAGE 2018-2019 The governance model continues to move forward. Operational and Policy Governance are clearly understood. The Board of Directors and Members have adapted well. Again, I stress how pleased I am to work with a team striving to improve our organization and game. The Board recognizes that hockey is a passion with high expectations from our country. The mandatory Initiation Program is experiencing some concern in a few areas; however, I have been impressed with the progress and attitude of the Members actively involved in promoting the value of this program. It is pleasant to receive compliments supporting the Board for this initiative. It is difficult to be critical of a program that works on improvement and develops skills as well as incorporating fun in the game. -

AN HONOURED PAST... and Bright Future an HONOURED PAST

2012 Induction Saturday, June 16, 2012 Convention Hall, Conexus Arts Centre, 200 Lakeshore Drive, Regina, Saskatchewan AN HONOURED PAST... and bright future AN HONOURED PAST... and bright future 2012 Induction Saturday, June 16, 2012 Convention Hall , Conexus Arts Centre, 200 Lakeshore Drive, Regina, Saskatchewan INDUCTION PROGRAM THE SASKATCHEWAN Master of Ceremonies: SPORTS HALL OF FAME Rod Pedersen 2011-12 Parade of Inductees BOARD OF DIRECTORS President: Hugh Vassos INDUCTION CEREMONY Vice President: Trent Fraser Treasurer: Reid Mossing Fiona Smith-Bell - Hockey Secretary: Scott Waters Don Clark - Wrestling Past President: Paul Spasoff Orland Kurtenbach - Hockey DIRECTORS: Darcey Busse - Volleyball Linda Burnham Judy Peddle - Athletics Steve Chisholm Donna Veale - Softball Jim Dundas Karin Lofstrom - Multi Sport Brooks Findlay Greg Indzeoski Vanessa Monar Enweani - Athletics Shirley Kowalski 2007 Saskatchewan Roughrider Football Team Scott MacQuarrie Michael Mintenko - Swimming Vance McNab Nomination Process Inductee Eligibility is as follows: ATHLETE: * Nominees must have represented sport with distinction in athletic competition; both in Saskatchewan and outside the province; or whose example has brought great credit to the sport and high respect for the individual; and whose conduct will not bring discredit to the SSHF. * Nominees must have compiled an outstanding record in one or more sports. * Nominees must be individuals with substantial connections to Saskatchewan. * Nominees do not have to be first recognized by a local satellite hall of fame, if available. * The Junior level of competition will be the minimum level of accomplishment considered for eligibility. * Regardless of age, if an individual competes in an open competition, a nomination will be considered. * Generally speaking, athletes will not be inducted for at least three (3) years after they have finished competing (retired). -

Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies Of

TENSIONS IN MENTORING: A QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE EXPERIENCES OF THE COACH MENTORING PROGRAM INSTITUTED BY HOCKEY MANITOBA BY STEVEN MACDONALD A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Faculty of Kinesiology and Recreation Management University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba Copyright © 2010 by Steven Macdonald Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-77368-0 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-77368-0 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Induction Spotlight Tsn/Rds Broadcast Zone Recent Acquisitions

HOCKEY HALL of FAME NEWS and EVENTS JOURNAL INDUCTION SPOTLIGHT TSN/RDS BROADCAST ZONE RECENT ACQUISITIONS SPRING 2015 CORPORATE MATTERS LETTER FROM THE INDUCTION 2015 • The annual elections meeting of the Selection Committee VICe-CHAIR will be held in Toronto on June 28 & 29, 2015 (with the announcement of the 2015 inductees on June 29th). Dear Teammates: • The Hockey Hall of Fame Induction Celebration will be held on Monday, November 9, 2015. Not long after another successful Graig Abel/HHOF Induction Celebration last November, the closely knit hockey community mourned the loss of two of ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING the game’s most accomplished and respected individuals in Pat • Scotty Bowman, David Branch, Brian Burke, Marc de Foy, Mike Gartner and Anders Quinn and Jean Beliveau. I have been privileged to get to know Hedberg were re-appointed each to a further term on the Selection Committee for the and work with these distinguished gentlemen throughout my 2015, 2016 and 2017 selection proceedings. life in hockey and like many others I was particularly heartened • The general voting Members ratified new By-law Nos. 25 and 26 which, among other by the outstanding tributes that spoke volumes to their impact amendments, provide for improved voting procedures applicable to all categories of on our great sport. Honoured Membership (visit HHOF.com for full transcripts). Although Chair of the Board for little more than a year, Pat left his mark on the Hockey Hall of Fame, overseeing the recruitment BOARD OF DIRECTORS Nominated by: of new members to the Selection Committee, initiating the Lanny McDonald, Chair (1) Corporate Governance Committee first comprehensive selection process review which led to Jim Gregory, Vice-Chair National Hockey League several by-law amendments, and establishing new and renewed Murray Costello Corporate Governance Committee partnerships. -

2014 Spring/Summer

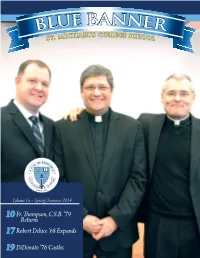

bbllue banner HAEL’S COLLEGE SC ST. MIC HOOL Volume 16 ~ Spring/Summer 2014 10 Fr. ompson, C.S.B. ’79 Returns 17 Robert Deluce ’68 Expands 19 DiDonato ’76 Castles lettersbb tol theu editore banner HAEL’S COLLEGE S ST. MIC CHOOL The St. Michael’s College School alumni magazine, Blue Banner, is published two times per year. It reflects the history, accomplishments and stories of graduates and its purpose is to promote collegiality, respect and Christian values under the direction of the Basilian Fathers. PRESIDENT: Terence M. Sheridan ’89 CONTACT DIRECTORY EDITOR: Gavin Davidson ’93 St. Michael’s College School: www.stmichaelscollegeschool.com CO-EDITOR: Michael De Pellegrin ’94 Blue Banner Online: www.mybluebanner.com CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Basilian Fathers: www.basilian.org Kimberley Bailey, Michael Flood ’87, Jillian Kaster, Pat CISAA (Varsity Athletic Schedule): www.cisaa.ca Mancuso ’90, Harold Moffat ’52, Marc Montemurro ’93, Twitter: www.twitter.com/smcs1852 Joe Younder ’56, Stephanie Nicholls, Terence Sheridan Advancement Office: [email protected] ’89. Alumni Affairs: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS Archives Office: [email protected] Blue Banner Feedback: [email protected] School Administration Message 4 Communications Office: [email protected] Alumni Association Message 5 Tel: 416-653-3180 ext. 292 Editor’s Letter 6 Fax: 416-653-8789 Letters to the Editor 7 E-mail: [email protected] Around St. Mike’s 8 • Admissions (ext. 195) Fr. Thompson, C.S.B. ’79 10 • Advancement (ext. 118) Returns Home as New President • Alumni Affairs (ext. 273) Securing Our Future by Giving Back: 12 Michael Flood ’87 • Archives (ext. -

Developmental Activities of Ontario Hockey League Players

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 2017 Developmental Activities of Ontario Hockey League Players William Joseph Garland University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Garland, William Joseph, "Developmental Activities of Ontario Hockey League Players" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 7357. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/7357 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. Developmental Activities of Ontario Hockey League Players By William Joseph Garland A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies through the Department of Kinesiology in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Human Kinetics at the University of Windsor Windsor, Ontario, Canada 2017 © 2017 William Joseph Garland Developmental Activities of Ontario Hockey League Players by William Joseph Garland APPROVED BY: ______________________________________________ D. Bussière Odette School of Business ______________________________________________ C. -

USA Hockey Annual Guide Text

2018- 19 Annual Guide USA HOCKEY, INC. Walter L. Bush, Jr. Center 1775 Bob Johnson Drive Colorado Springs, CO 80906- 4090 (719) 576- USAH (8724) • [email protected] usahockey.com EXECUTIVE OFFICE Susan Hunt 132 THE USA HOCKEY FOUNDATION Pat Kelleher 114 Manager, Member Services Katie Guay (401) 743-6880 Executive Director Rachel Hyman 129 Director, Philanthropy Amanda Raider 165 Member Services/Officiating Administrator Mellissa Lewis 106 Executive Assistant Jeremy Kennedy 117 Manager, Annual Giving Dave Ogrean 163 Manager, Membership and Sheila May 107 Advisor to the President Disabled Hockey Manager, Grants & Stewardship Pat Knowlton 113 HOCKEY OPERATIONS Tamara Tranter 164 Coordinator, Adult Hockey Senior Director, Development Scott Aldrich 174 Julie Rebitski 131 Manager, Hockey Operations Regional Specialist, Member Services NATIONAL TEAM (734) 453-6400 Joe Bonnett 108 Debbie Riggleman 128 DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM ADM Regional Manager Regional Specialist, Member Services Seth Appert 314 Marc Boxer 147 U.S. National Development Coach Director, Junior Hockey Shannon Webster 118 Manager, Program Services Sydney Blackman 330 Dan Brennan 177 Brian Fishman Intern – NTDP Director, Sled & Inline National Teams/ TBD 102 Manager, Coaching Education Program Coordinator, Club Excellence Brock Bradley 320 Head Equipment Manager Reagan Carey 154 FINANCE & ADMINISTRATION Director, Women’s Hockey Rick Comley 308 Kevin Buckner 104 Assistant Director, Player Personnel Helen Fenlon 127 Shipping & Receiving Clerk Manager, Officiating Administration Nick -

2018-19 Annual Guide 4090 Usahockey.Com USA HOCKEY, INC

2018- 19 Annual Guide USA HOCKEY, INC. Walter L. Bush, Jr. Center 1775 Bob Johnson Drive Colorado Springs, CO 80906- 4090 (719) 576- USAH (8724) • [email protected] usahockey.com EXECUTIVE OFFICE Andy Gibson 115 THE USA HOCKEY FOUNDATION Pat Kelleher 114 Manager, Program Services Katie Guay (401) 743-6880 Executive Director Katie Holmgren 120 Director, Philanthropy Amanda Raider 165 Director, Program Services Sheila May 107 Executive Assistant Susan Hunt 132 Manager, Grants & Stewardship Dave Ogrean 163 Manager, Member Services Zachary May (612) 202-1974 Advisor to the President Rachel Hyman 129 Director, Philanthropy Member Services/Officiating Administrator HOCKEY OPERATIONS Tamara Tranter 164 Jeremy Kennedy 117 Senior Director, Development Scott Aldrich 174 Manager, Membership and Manager, Hockey Operations NATIONAL TEAM (734) 453-6400 Disabled Hockey Joe Bonnett 108 DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM ADM Regional Manager Julie Rebitski 131 Seth Appert 314 Regional Specialist, Member Services Marc Boxer 147 U.S. National Development Coach Director, Junior Hockey Debbie Riggleman 128 Sydney Blackman 330 Regional Specialist, Member Services Dan Brennan 177 Brian Fishman Intern – NTDP Director, Sled & Inline National Teams/ Shannon Webster 118 Rod Braceful 380 Manager, Coaching Education Program Manager, Program Services Assistant Director, Player Personnel Helen Fenlon 127 FINANCE & ADMINISTRATION Brock Bradley 320 Manager, Officiating Administration Kevin Buckner 104 Head Equipment Manager Guy Gosselin (719) 337-4404 Shipping & Receiving Clerk Nick -

SASKATCHEWAN JUNIOR "A" HOCKEY and WITHDRAWAL RATES from HIGH SCHOOL by MICHAEL THOMAS Mcdowell B.P.E. University of B

SASKATCHEWAN JUNIOR "A" HOCKEY AND WITHDRAWAL RATES FROM HIGH SCHOOL by MICHAEL THOMAS McDOWELL B.P.E. University of British Columbia, 1968 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION in the School of Physical Education and Recreation We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard 'THE UNIVERSITY OF^BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1969 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and Study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thes.is for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Physical Education and Recreation The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada Date April, 1969 ABSTRACT The thesis studied the withdrawal rates from high school of Junior "A" hockey players as compared to the general population in the Province of Saskatchewan. As a post hoc consideration, two additional aspects were examined: a) The effect the new N.H.L.-C.A.H.A. Agreement has had on the withdrawal rates of the Junior "A" student hockey players. b) The graduating age of Junior "A" hockey players. The selected sample size numbered 273 Junior "A" hockey players. These players were selected from the Saskatchewan Junior Hockey League registry for the six years of 1959-61 and 1962-66. -

2008 Fall/Winter

Volume 5 — Fall 2008 blue banner Remarkable Models of Friendship & Giving Our History has the Stuff of Myth Still Flying High on a Wing and a Prayer St. Mike’s Authors St. Michael’s College School blue banner The St. Michael’s College School Alumni Magazine, Blue Banner, is published two times per year. It refl ects the history, accomplishments and stories of graduates and its purpose is to promote collegiality, respect and Christian values under the direction of the Basilian Fathers. President: Fr. Joseph Redican, C.S.B. Editor: Joe Younder ’56 Co-editor: Michael De Pellegrin ’94 Tel: 416-653-3180 ext. 292 e-mail: [email protected] Fax: 416-653-8789 alumni e-mail: [email protected] Canada Publications Mail Agreement #40006997 Contributing Editors Romeo Milano ’80, Peter Grbac ’08, Ted Schmidt ’57, Larry Colle ’69, Richard McQuade, Frank Kielty ’54, Tom O’Brien ’57 Alumni Executive 2008-09 President: Romeo Milano ‘80 Past President: Peter Thurton ‘81 Vice President: Josh Colle ‘92 Vice President: Marc Montemurro ‘93 Treasurer: Anthony Scilipoti ‘90 Secretary: Paul Nusca ‘96 Councillors Marco Berardi ’84 Dennis Mills ’64 Wiz Khayat ’96 Dominic DeLuca ’76 Andre Tilban ’03 John Teskey ’00 Rui DeSousa ’88 Dominic Montemurro ’78 Paul Thomson ’65 Frank Di Nino ’80 John O’Neill ’86 James MacDonald ’72 ‘xx Art Rubino ’81 Past Presidents Peter Thurton, Denis Caponi Jr., Rob Grossi, Paul Grossi, Daniel Brennan, John McCusker, William Metzler, Michael Duffy, Ross Robertson, William Rosenitsch, Paul Thomson, John G. Walsh, Frank Thickett, W. Frank Morneau, Frank Glionna (Deceased), George Cormack, Richard Wakely (Deceased), Gordon Ashworth (Deceased), Peter D’Agostino (Deceased), G.J.