Mediaworks Television: Death of a Thousand Cuts?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where Are the Audiences?

WHERE ARE THE AUDIENCES? Full Report Introduction • New Zealand On Air (NZ On Air) supports and funds audio and visual public media content for New Zealand audiences. It does so through the platform neutral NZ Media Fund which has four streams; scripted, factual, music, and platforms. • Given the platform neutrality of this fund and the need to efficiently and effectively reach both mass and targeted audiences, it is essential NZ On Air have an accurate understanding of the current and evolving behaviour of NZ audiences. • To this end NZ On Air conduct the research study Where Are The Audiences? every two years. The 2014 benchmark study established a point in time view of audience behaviour. The 2016 study identified how audience behaviour had shifted over time. • This document presents the findings of the 2018 study and documents how far the trends revealed in 2016 have moved and identify any new trends evident in NZ audience behaviour. • Since the 2016 study the media environment has continued to evolve. Key changes include: − Ongoing PUTs declines − Anecdotally at least, falling SKY TV subscription and growth of NZ based SVOD services − New TV channels (eg. Bravo, HGTV, Viceland, Jones! Too) and the closure of others (eg. FOUR, TVNZ Kidzone, The Zone) • The 2018 Where Are The Audiences? study aims to hold a mirror up to New Zealand and its people and: − Inform NZ On Air’s content and platform strategy as well as specific content proposals − Continue to position NZ On Air as a thought and knowledge leader with stakeholders including Government, broadcasters and platform owners, content producers, and journalists. -

Proactive Release

IN CONFIDENCE DEV-21-MIN-0097 Cabinet Economic Development Committee Minute of Decision This document contains information for the New Zealand Cabinet. It must be treated in confidence and handled in accordance with any security classification, or other endorsement. The information can only be released, including under the Official Information Act 1982, by persons with the appropriate authority. Modernising Landonline: Progress Update March 2021 Portfolio Land Information On 12 May 2021, the Cabinet Economic Development Committee: 1 noted that the Landonline rebuild is within budget and on track for delivery; 2 noted that Land Information New Zealand (LINZ) began the rebuild of core IT systems in August 2020 after completing detailed planning and building capacity; 3 noted that an independent Gateway review in May 2020 rated LINZ’s readiness to proceed with the core system rebuild as Green/Amber; 4 noted that the programme has developed and releasedRelease four Search and Notices products introducing early improvements to how Landonline customers (including the public, territorial authorities, and financial institutions) access LINZ property data; 5 noted that financial approvals from the Minister of Finance, Minister of Land Information, and Minister for the Digital Economy and Communications (joint Ministers) in April 2019 and August 2020 will maintain programme activity until December 2021; 6 noted that reforecast whole-of-life costs prepared for the August 2020 financial approval provided confidence that the programme can be delivered -

Important On-Line Safety Message from MOE, N4L, Netsafe NZ

COVID-19 update 19th August 2020 Some reminders to all of our school families and whanau As you are aware, the Level 3 lockdown restrictions in Auckland will be in force until 11.59pm Wednesday 26th August, which includes 8 school days. Cabinet will review this decision on Friday 21st August and formally consider Alert Levels on Monday 24th August. Hopefully it will be a short, sharp lockdown. We have an amazing community, so working together and supporting each other, we will get through this once again. If anyone requires additional support please contact the school or your child/ren’s teacher. MOE support with television and radio: Home Learning TV | Papa Kāinga TV will be back on Monday 17 August to support learning for children aged 2-to-11 years while Auckland remains in Alert Level 3. Home Learning TV | Papa Kāinga TV will take over TVNZ DUKE's daytime schedule 9am to 1pm on weekdays. Programming for younger children includes the popular Karen’s House at 9am, followed by programmes for children aged 5 to 7, including junior movement with the Dingle Foundation and junior science and maths with Suzy Cato. DUKE is available on Freeview channel 13, Sky and Vodafone TV channel 23. It can be live streamed on the TVNZ website, www.tvnz.co.nz. Content will be available for catch up viewing on TVNZ OnDemand. Important On-line Safety Message from MOE, N4L, Netsafe NZ Firstly, we hope your wider school community is safe and well as we navigate our restricted world again. We wanted to take this opportunity to remind you that our free safety filter is available to help protect ākonga from the worst of the web while they are learning from home. -

Manufacturer Proposal Template

LITMUS TESTING 2015 PREPARED FOR: BROADCASTING STANDARDS AUTHORITY Litmus Testing 2015 Report Prepared For Broadcasting Standards Authority Client Contact Karen Scott-Howman Nielsen Contact Jade Phillips Date 8th June 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Objectives and Research Approach .............................................................................................................. 7 Overview of Findings ................................................................................................................................... 10 Allen and Mediaworks TV Ltd – 2014-106: National Party election advertisement .................................................. 13 Bolton and Radio New Zealand Ltd – 2009-166: Allegations of anti-Semitism on National Radio ............................ 16 Cumin and The Radio Network Ltd – 2014-098: Rachel Smalley on Israel-Hamas conflict ....................................... 19 Dempsey and 3 others and Television New Zealand Ltd – 2014-047: Mike Hosking and climate change ................ 22 Emirates Team NZ and The Radio Network Ltd – 2014-089: Alleged resignation of Team NZ designer ................... 25 General discussion to provide context for broadcasters and for the BSA .................................................. 28 Concluding summary ................................................................................................................................. -

2019 Winners & Finalists

2019 WINNERS & FINALISTS Associated Craft Award Winner Alison Watt The Radio Bureau Finalists MediaWorks Trade Marketing Team MediaWorks MediaWorks Radio Integration Team MediaWorks Best Community Campaign Winner Dena Roberts, Dominic Harvey, Tom McKenzie, Bex Dewhurst, Ryan Rathbone, Lucy 5 Marathons in 5 Days The Edge Network Carthew, Lucy Hills, Clinton Randell, Megan Annear, Ricky Bannister Finalists Leanne Hutchinson, Jason Gunn, Jay-Jay Feeney, Todd Fisher, Matt Anderson, Shae Jingle Bail More FM Network Osborne, Abby Quinn, Mel Low, Talia Purser Petition for Pride Mel Toomey, Casey Sullivan, Daniel Mac The Edge Wellington Best Content Best Content Director Winner Ryan Rathbone The Edge Network Finalists Ross Flahive ZM Network Christian Boston More FM Network Best Creative Feature Winner Whostalk ZB Phil Guyan, Josh Couch, Grace Bucknell, Phil Yule, Mike Hosking, Daryl Habraken Newstalk ZB Network / CBA Finalists Tarore John Cowan, Josh Couch, Rangi Kipa, Phil Yule Newstalk ZB Network / CBA Poo Towns of New Zealand Jeremy Pickford, Duncan Heyde, Thane Kirby, Jack Honeybone, Roisin Kelly The Rock Network Best Podcast Winner Gone Fishing Adam Dudding, Amy Maas, Tim Watkin, Justin Gregory, Rangi Powick, Jason Dorday RNZ National / Stuff Finalists Black Sheep William Ray, Tim Watkin RNZ National BANG! Melody Thomas, Tim Watkin RNZ National Best Show Producer - Music Show Winner Jeremy Pickford The Rock Drive with Thane & Dunc The Rock Network Finalists Alexandra Mullin The Edge Breakfast with Dom, Meg & Randell The Edge Network Ryan -

Briefing to the Incoming Minister

Briefing to the Incoming Minister From the Auckland Languages Strategy Working Group November 2017 To: Rt Hon Jacinda Ardern, Minister of Arts, Culture and Heritage Hon Chris Hipkins, Minister of Education Hon Nanaia Mahuta, Minister of Māori Development Hon Jenny Salesa, Minister of Ethnic Communities and Associate Minister of Education, Health and Housing and Urban Development Hon Aupito William Si’o, Minister of Pacific Peoples and Associate Minister of Justice and of Courts Copy to: Hon Winston Peters, Minister of Foreign Affairs Hon Kelvin Davis, Minister of Crown-Māori Relations and of Corrections, Associate Minister of Education Hon Grant Robertson, Associate Minister of Arts, Culture and Heritage Hon Phil Twyford, Minister of Housing and Urban Development Hon Andrew Little, Minister of Justice and Minister of Courts Hon Carmel Sepuloni, Minister of Social Development and Associate Minister of Pacific Peoples and of Arts, Culture and Heritage Hon Dr David Clark, Minister of Health Hon David Parker, Minister of Economic Development Hon Iain Lees-Galloway, Minister of Immigration Hon Clare Curran, Minister of Broadcasting, Communications and Digital Media Hon Tracey Martin, Minister of Internal Affairs and Associate Minister of Education Hon Shane Jones, Minister of Regional Economic Development Hon Kris Fa’afoi, Associate Minister of Immigration Hon Peeni Henare, Associate Minister of Social Development Hon Willie Jackson, Minister of Employment and Associate Minister of Māori Development Hon Meka Whaitiri, Associate Minister of Crown-Māori Relations Hon Julie Ann Gentner, Minister of Women and Associate Minister of Health Hon Michael Wood, Parliamentary Under-Secretary to the Minister for Ethnic Communities Hon Fletcher Tabuteau, Parliamentary Under-Secretary to the Minister of Foreign Affairs Hon Jan Logie, Parliamentary Under-Secretary to the Minister of Justice 1 Introduction Aotearoa New Zealand’s increasing language diversity is a potential strength for social cohesion, identity, trade, tourism, education achievement and intercultural understanding. -

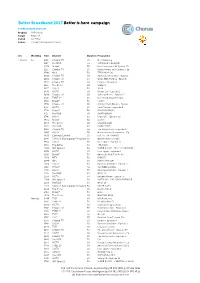

BB2017 Media Overview for Rsps

Better Broadband 2017 Better is here campaign TV PRE AIRDATE SPOTLIST Product All Products Target All 25-54 Period wc 7 May Source TVmap/The Nielsen Company w/c WeekDay Time Channel Duration Programme 7 May 17 Su 1112 Choice TV 30 No Advertising 7 May 17 Su 1217 the BOX 60 SURVIVOR: CAGAYAN 7 May 17 Su 1220 Bravo* 30 Real Housewives Of Sydney, Th 7 May 17 Su 1225 Choice TV 30 Better Homes and Gardens - Ep 7 May 17 Su 1340 MTV 30 TEEN MOM OG 7 May 17 Su 1410 Choice TV 30 American Restoration - Episod 7 May 17 Su 1454 Choice TV 60 Walks With My Dog - Episode 7 May 17 Su 1542 Choice TV 60 Empire - Episode 4 7 May 17 Su 1615 The Zone 60 SLIDERS 7 May 17 Su 1617 HGTV 30 16:00 7 May 17 Su 1640 HGTV 60 Hawaii Life - Episode 2 7 May 17 Su 1650 Choice TV 60 Jamie at Home - Episode 5 7 May 17 Su 1710 TVNZ 2* 60 Home and Away Omnibus 7 May 17 Su 1710 Bravo* 30 Catfish 7 May 17 Su 1710 Choice TV 30 Jimmy's Farm Diaries - Episod 7 May 17 Su 1717 HGTV 30 Yard Crashers - Episode 8 7 May 17 Su 1720 Prime* 30 RUGBY NATION 7 May 17 Su 1727 the BOX 30 SMACKDOWN 7 May 17 Su 1746 HGTV 60 Island Life - Episode 10 7 May 17 Su 1820 Bravo* 30 Catfish 7 May 17 Su 1854 The Zone 60 WIZARD WARS 7 May 17 Su 1905 the BOX 30 MAIN EVENT 7 May 17 Su 1906 Choice TV 60 The Living Room - Episode 37 7 May 17 Su 1906 HGTV 30 House Hunters Renovation - Ep 7 May 17 Su 1930 Comedy Central 30 LIVE AT THE APOLLO 7 May 17 Su 1945 Crime & Investigation Network 30 DEATH ROW STORIES 7 May 17 Su 1954 HGTV 30 Fixer Upper - Episode 6 7 May 17 Su 1955 The Zone 60 THE CAPE 7 May 17 Su 2000 -

Drugs, Guns and Gangs’: Case Studies on Pacific States and How They Deploy NZ Media Regulators

‘BACK TO THE SOURCE’ 7. ‘Drugs, guns and gangs’: Case studies on Pacific states and how they deploy NZ media regulators ABSTRACT Media freedom and the capacity for investigative journalism have been steadily eroded in the South Pacific in the past five years in the wake of an entrenched coup and censorship in Fiji. The muzzling of the Fiji press, for decades one of the Pacific’s media trendsetters, has led to the emergence of a culture of self-censorship and a trend in some Pacific countries to harness New Zealand’s regulatory and self-regulatory media mechanisms to stifle unflattering reportage. The regulatory Broadcasting Standards Authority (BSA) and the self-regulatory NZ Press Council have made a total of four adjudications on complaints by both the Fiji military-backed regime and the Samoan government and in one case a NZ cabinet minister. The complaints have been twice against Fairfax New Zealand media—targeting a prominent regional print journalist with the first complaint in March 2008—and twice against television journalists, one of them against the highly rated current affairs programme Campbell Live. One complaint, over the reporting of Fiji, was made by NZ’s Rugby World Cup Minister. All but one of the complaints have been upheld by the regulatory/self-regulatory bodies. The one unsuccessful complaint is currently the subject of a High Court appeal by the Samoan Attorney-General’s Office and is over a television report that won the journalists concerned an investigative journalism award. This article examines case studies around this growing trend and explores the strategic impact on regional media and investigative journalism. -

Issue 07 2017

Colossal Anticlimax Greener Pastures In Like Gillian Flynn Jordan Margetts watches the latest kaiju film, is Jack Adams tells us why we’ve got to let it berm, Caitlin Abley attempts to reinvent herself with a not blown (Anne Hath)away let it berm, gotta let it berm daytrip and a doo-rag [1] The University of Auckland School of Music GRAD GALA CONCERTO COMPETITION 10th Anniversary Thursday 4 May, 7.30pm, Auckland Town Hall. JOELLA PINTO JULIE PARK SARA LEE TCHAIKOVSKY CECIL FORSYTH TCHAIKOVSKY Violin Concerto in D major, Concerto for Viola and Piano Concerto No. 1 Op. 35 Mvt. I Orchestra in G minor Mvt. I, III in B flat minor, Op. 23 Mvt. I Free admission Patrons are strongly advised to arrive early to be assured of admission. ISSUE SEVEN CONTENTS 9 10 NEWS COMMUNITY STAMPING FEET FOR SHAKING UP THE SCIENCE SYSTEM Recapping the worldwide Less awareness, more tangible Marches for Science results needed for mental health 13 20 LIFESTYLE FEATURES TEA-RIFFIC YOU HAVIN’ A LAUGH? Different teas to dip your Craccum’s guide to the NZ Inter- bikkies into national Comedy Festival 24 34 ARTS COLUMNS REMEMBERING CARRIE SYMPHONIC FISHER SATISFACTION The stars will be shining a little Michael Clark takes a look at the brighter this May 4th magic of music in media [3] PRO1159_013_CRA SHAPE YOUR CAREER SHAPE OUR CITY We offer opportunities for graduates and students from a range of different disciplines. Applications for our Auckland Council 2018 Graduate and 2017 Intern Programmes will be open between 24 April – 11 May. -

Schedule of Responsibilities Delegated to Associate Ministers and Parliamentary Under-Secretaries

Schedule of Responsibilities Delegated to Associate Ministers and Parliamentary Under-Secretaries 14 June 2018 276641v1 This paper is presented to the House, in accordance with the suggestion of the Standing Orders Committee in its Report on the Review of Standing Orders [I. 18A, December 1995]. At page 76 of its report, the Standing Orders Committee recorded its support for oral questions to be asked directly of Associate Ministers who have been formally delegated defined responsibilities by Ministers having primary responsibility for particular portfolios. The Standing Orders Committee proposed that the Leader of the House should table in the House a schedule of such delegations at least annually. The attached schedule has been prepared in the Cabinet Office for this purpose. The schedule also includes responsibilities allocated to Parliamentary Under-Secretaries. Under Standing Orders, Parliamentary Under-Secretaries may only be asked oral questions in the House in the same way that any MP who is not a Minister can be questioned. However, they may answer questions on behalf of the principal Minister in the same way that Associate Ministers can answer. The delegations are also included in the Cabinet Office section of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet website (http://www.dpmc.govt.nz/cabinet/ministers/delegated), which will be updated from time to time to reflect any substantive amendments to any of the delegated responsibilities. Hon Chris Hipkins Leader of the House June 2018 276641v1 2 Schedule of Responsibilities Delegated to Associate Ministers and Parliamentary Under-Secretaries as at 14 June 2018 Associate Ministers are appointed to provide portfolio Ministers with assistance in carrying out their portfolio responsibilities. -

Rt Hon Jacinda Ardern, Prime Minister Hon Kris Faafoi Hon Stuart Nash

Rt Hon Jacinda Ardern, Prime Minister Hon Kris Faafoi Hon Stuart Nash Hon Grant Robertson Hon Simon Bridges Hon Paul Goldsmith Hon Todd McClay Parliament Building Wellington, 6160 16 April 2020 Dear Prime Minister, Government Ministers and Opposition Members of Parliament COVID-19 effect on small business leases – call for urgent action to be taken to prevent business closures We refer to our previous letter to each of you dated 2 April 2020. In our letter we wrote: a) calling for urgent action to be taken to prevent business closures; and b) we implored you to address the critical issue of rent relief to all tenants of commercial leases – as many leases do not provide any rent relief. We have had no response from government or the Ministry for Business, Innovation & Employment to our letter and our views do not appear to have been considered in the recent package that was announced yesterday to supposedly assist small to medium-sized businesses. We find this very disappointing. As we said in our letter, we are the peak body representing franchising in NZ. Turnover of the franchising sector represents circa 11% of New Zealand’s GDP. As such franchising is a critical part of the New Zealand economy. And most of the circa 37,000 franchisees in NZ are small businesses – the very people that the government has said need more government support. In our letter we explained to you why rent relief is critical and why we believe urgent action needs to be taken to put cash in the hands of small to medium-sized business owners. -

Thinktv FACT PACK NEW ZEALAND

ThinkTV FACT PACK JAN TO DEC 2017 NEW ZEALAND TV Has Changed NEW ZEALAND Today’s TV is a sensory experience enjoyed by over 3 million viewers every week. Powered by new technologies to make TV available to New Zealanders anywhere, any time on any screen. To help advertisers and agencies understand how TV evolved over the last year, ThinkTV has created a Fact Pack with all the stats for New Zealand TV. ThinkTV’s Fact Pack summarises the New Zealand TV marketplace, in-home TV viewing, timeshifted viewing and online video consumption. And, because we know today’s TV is powered by amazing content, we’ve included information on some top shows, top advertisers and top adverts to provide you with an insight into what was watched by New Zealanders in 2017. 2017 THE NEW ZEALAND TV MARKETPLACE BIG, SMALL, MOBILE, SMART, CONNECTED, 1. HD-capable TV sets are now in CURVED, VIRTUAL, 3D, virtually every home in New Zealand DELAYED, HD, 4K, 2. Each home now has on average ON-DEMAND, CAST, 7.6 screens capable of viewing video STREAM… 3. Almost 1 in every 3 homes has a internet-connected smart TV THE TV IS AS CENTRAL TO OUR ENTERTAINMENT AS IT’S EVER BEEN. BUT FIRST, A QUICK PEAK INSIDE NEW ZEALAND’S LIVING ROOMS • In 2015 New Zealand TV celebrated 55 years of broadcast with the first transmission on 1 June, 1960 • Today’s TV experience includes Four HD Free-to-air channels Two Commercial Free-to-Air broadcasters One Subscription TV provider • Today’s TV is DIGITAL in fact, Digital TV debuted in 2006 followed by multi-channels in 2007 • In its 58th year, New Zealand TV continues to change and evolve.