Social Media, Political Campaigning and the Unbearable Lightness of Being There

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Briefing to the Incoming Minister

Briefing to the Incoming Minister From the Auckland Languages Strategy Working Group November 2017 To: Rt Hon Jacinda Ardern, Minister of Arts, Culture and Heritage Hon Chris Hipkins, Minister of Education Hon Nanaia Mahuta, Minister of Māori Development Hon Jenny Salesa, Minister of Ethnic Communities and Associate Minister of Education, Health and Housing and Urban Development Hon Aupito William Si’o, Minister of Pacific Peoples and Associate Minister of Justice and of Courts Copy to: Hon Winston Peters, Minister of Foreign Affairs Hon Kelvin Davis, Minister of Crown-Māori Relations and of Corrections, Associate Minister of Education Hon Grant Robertson, Associate Minister of Arts, Culture and Heritage Hon Phil Twyford, Minister of Housing and Urban Development Hon Andrew Little, Minister of Justice and Minister of Courts Hon Carmel Sepuloni, Minister of Social Development and Associate Minister of Pacific Peoples and of Arts, Culture and Heritage Hon Dr David Clark, Minister of Health Hon David Parker, Minister of Economic Development Hon Iain Lees-Galloway, Minister of Immigration Hon Clare Curran, Minister of Broadcasting, Communications and Digital Media Hon Tracey Martin, Minister of Internal Affairs and Associate Minister of Education Hon Shane Jones, Minister of Regional Economic Development Hon Kris Fa’afoi, Associate Minister of Immigration Hon Peeni Henare, Associate Minister of Social Development Hon Willie Jackson, Minister of Employment and Associate Minister of Māori Development Hon Meka Whaitiri, Associate Minister of Crown-Māori Relations Hon Julie Ann Gentner, Minister of Women and Associate Minister of Health Hon Michael Wood, Parliamentary Under-Secretary to the Minister for Ethnic Communities Hon Fletcher Tabuteau, Parliamentary Under-Secretary to the Minister of Foreign Affairs Hon Jan Logie, Parliamentary Under-Secretary to the Minister of Justice 1 Introduction Aotearoa New Zealand’s increasing language diversity is a potential strength for social cohesion, identity, trade, tourism, education achievement and intercultural understanding. -

Schedule of Responsibilities Delegated to Associate Ministers and Parliamentary Under-Secretaries

Schedule of Responsibilities Delegated to Associate Ministers and Parliamentary Under-Secretaries 14 June 2018 276641v1 This paper is presented to the House, in accordance with the suggestion of the Standing Orders Committee in its Report on the Review of Standing Orders [I. 18A, December 1995]. At page 76 of its report, the Standing Orders Committee recorded its support for oral questions to be asked directly of Associate Ministers who have been formally delegated defined responsibilities by Ministers having primary responsibility for particular portfolios. The Standing Orders Committee proposed that the Leader of the House should table in the House a schedule of such delegations at least annually. The attached schedule has been prepared in the Cabinet Office for this purpose. The schedule also includes responsibilities allocated to Parliamentary Under-Secretaries. Under Standing Orders, Parliamentary Under-Secretaries may only be asked oral questions in the House in the same way that any MP who is not a Minister can be questioned. However, they may answer questions on behalf of the principal Minister in the same way that Associate Ministers can answer. The delegations are also included in the Cabinet Office section of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet website (http://www.dpmc.govt.nz/cabinet/ministers/delegated), which will be updated from time to time to reflect any substantive amendments to any of the delegated responsibilities. Hon Chris Hipkins Leader of the House June 2018 276641v1 2 Schedule of Responsibilities Delegated to Associate Ministers and Parliamentary Under-Secretaries as at 14 June 2018 Associate Ministers are appointed to provide portfolio Ministers with assistance in carrying out their portfolio responsibilities. -

中醫院 Master Clinic 提供 ACC 諮詢:09 443 3355 預約:021 042 4342 診察治療

免費報紙 一戶一份* *免費取報條款: 每戶限取一份免費報紙。 如果您替他人代取, 最多代取三份。 超過限額者需按每份$4向看中國辦公室付款。 違規者將被追究法律責任。 *Free Newspaper T&C: LIMIT to ONE free copy per household. Additional copy charges $4 each, please pay in advance to Vision Times office. Legal action will be taken against those who breach above terms. www.kanzhongguo.com 新西蘭版 第526期 2020年7月31日 星期五 電話:09-5803182 信箱:[email protected] 美國國務卿蓬佩奧在尼克松總統圖書館發表對華政策重磅演講。 (David McNew/Getty Images) 4版 美國務卿蓬佩奧發表對華政策重磅演講 8-9版 蓬佩奧演講全文 中醫院 Master Clinic 提供 ACC 諮詢:09 443 3355 預約:021 042 4342 診察治療 鼻炎,各種萎縮,哮喘,過敏 , 耳鳴 , 頭痛 , 胃痛 , 胃炎 , 反胃 , 癱瘓 , 神經炎 , 肝炎 , 過度勞累 , 糖尿病 , 高血壓 , 痛風 , 皮疹 , 皮膚乾燥,濕疹,關節炎 , 骨折 , 腰酸背痛 , 痛經 , 月經失調 , 不孕 , 癌症術後和中風 恢復 , 治療未知疾病 , 美容 , 減肥 , 兒童生長 , 矯正姿勢 治療類別 針灸 , 特色推拿 10 分鐘 , 耳灸 , 中藥(失眠、減肥等), 拔罐 中藥中心 中草藥批發零售 營業時間:週一至週三和週六 8:30-18:00 週四至週五 8:30-21:00 週日 10:00-17:30(晚間時間可預約) 地址:Shop 215(Countdown 隔壁 /Bin in 對面 ),Master Clinic,Glenfield Mall,Cnr Glenfield Rd & Downing St.Glenfield 2 看紐國 New Zealand 2020年7月31日 誰需要付防疫隔離費?政府達成妥協方案 看中國記者鹿鳴綜合報導 據悉,國家黨和優先黨都要求對入境人員統一收 取隔離費用,工黨則模棱兩可,綠黨則堅決反對。最 從上週四(7 月 23 日)至本週三(7 月 29 日), 後出台的方案是執政聯盟(工黨、優先黨、綠黨)達 紐西蘭新增中共病毒(COVID-19)感染案例共為四例, 成的妥協方案。估算根據該方案國家只能最終收取千 均發生在入境被隔離人群中,並且已連續 89 天未出現 萬元的隔離費用,與總共上億元的隔離費用支出相 社區感染案例。截至目前,仍活躍的病例有 23 例,均 比,不到十分之一。 在隔離中。 自 3 月 26 日以來,已有 32,221 人在國內 32 個隔 本週早些時候,一名男子從紐西蘭飛往韓國,入 離設施中進行了隔離,目前全紐西蘭的隔離床位共有 境後被診斷為 COVID-19 陽性,引起關注。目前推斷該 6,100 個。鑒於入境人數持續高企,隔離設施面臨不 男子是在新加坡機場轉機時染疫,該男子在新加坡機 足,紐西蘭航空本週宣布國際航班的預定暫停將再次 場中轉時於休息室待了 14 小時 20 分鐘,與來自其他 延長,至 8 月 9 日。同時,紐航也宣布暫停飛往澳洲 國家的乘客共處一室,但紐西蘭衛生部尚無法完全排 航班的機票預定,直至 8 月 28 日。 除該患者在紐西蘭國內感染的可能性。 雖然自疫情爆發以來,紐西蘭現已完成超過 -

Ministerial List 24 August 2018

Ministerial List 24 August 2018 Notes: 1. All Ministers are members of the Executive Council. 2. The Parliamentary Under-Secretaries are part of executive government, but are not members of the Executive Council. 3. Portfolios are listed in the left-hand column. Other responsibilities assigned by the Prime Minister are listed in the right-hand column. CABINET MINISTERS Portfolios Other responsibilities 1 Rt Hon Jacinda Ardern Prime Minister Minister for Child Poverty Reduction Minister for Arts, Culture and Heritage Minister for National Security and Intelligence 2 Rt Hon Winston Peters Deputy Prime Minister Minister of Foreign Affairs Minister for Disarmament and Arms Control Minister for State Owned Enterprises Minister for Racing 3 Hon Kelvin Davis Minister for Crown/Māori Relations Associate Minister of Education (Māori Minister of Corrections Education) Minister of Tourism 4 Hon Grant Robertson Minister of Finance1 Associate Minister for Arts, Culture and Minister for Sport and Recreation Heritage 1 The Finance portfolio includes the responsibilities formerly included within the Regulatory Reform portfolio. 279991v1 1 CABINET MINISTERS Portfolios Other responsibilities 5 Hon Phil Twyford Minister of Housing and Urban Development2 Minister of Transport 6 Hon Dr Megan Woods Minister of Energy and Resources Minister Responsible for the Earthquake Minister for Greater Christchurch Regeneration Commission Minister for Government Digital Services Minister of Research, Science and Innovation 7 Hon Chris Hipkins Minister of Education3 Leader -

Theparliamentarian

th 100 anniversary issue 1920-2020 TheParliamentarian Journal of the Parliaments of the Commonwealth 2020 | Volume 101 | Issue One | Price £14 SPECIAL CENTENARY ISSUE: A century of publishing The Parliamentarian, the Journal of Commonwealth Parliaments, 1920-2020 PAGES 24-25 PLUS The Commonwealth Building Commonwealth Votes for 16 year Promoting global Secretary-General looks links in the Post-Brexit olds and institutional equality in the ahead to CHOGM 2020 World: A view from reforms at the Welsh Commonwealth in Rwanda Gibraltar Assembly PAGE 26 PAGE 30 PAGE 34 PAGE 40 CPA Masterclasses STATEMENT OF PURPOSE The Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (CPA) exists to connect, develop, promote and support Parliamentarians and their staff to identify benchmarks of good governance, and Online video Masterclasses build an informed implement the enduring values of the Commonwealth. parliamentary community across the Commonwealth Calendar of Forthcoming Events and promote peer-to-peer learning 2020 Confirmed as of 24 February 2020 CPA Masterclasses are ‘bite sized’ video briefings and analyses of critical policy areas March and parliamentary procedural matters by renowned experts that can be accessed by Sunday 8 March 2020 International Women's Day the CPA’s membership of Members of Parliament and parliamentary staff across the Monday 9 March 2020 Commonwealth Day 17 to 19 March 2020 Commonwealth Association of Public Accounts Committees (CAPAC) Conference, London, UK Commonwealth ‘on demand’ to support their work. April 24 to 28 April 2020 -

David Clark MP

A community newsletter for the people of Dunedin North from the office of David Clark, MP June 2012 David Clark MP Greetings. At last November’s general election I was elected to represent the people of Dunedin North. I am the Labour party’s replacement for Pete Hodgson, who committed himself to serving Dunedin North for 21 years. My staff and I want to use this newsletter to keep people up to date about the work we are doing, and to discuss issues facing Dunedin and the wider community. For those of you I haven’t yet met, here’s a little about me: I’ve been the Warden at Selwyn College, worked on farms and in factories, worked as a Presbyterian Minister and celebrant, and as a Treasury analyst. And I’ve served on the Otago Community Trust as Deputy Chair. I’m committed to helping create a stronger, more caring society. I am passionate about Dunedin, and I will bring Claire Curran, Martin McArthur from Cadbury’s, David Clark and Labour leader David Shearer on a tour of Cadbury’s considerable energy and wide experience to the task of factory recently. representing this electorate. Hola, hola, holidays On my first regular sitting day as an MP, I had my Waitangi Day and Anzac Day. The glaring anomaly means Member’s Bill drawn from the ballot. I’m getting plenty of at least one of the holidays is lost every seven years, ribbing from some senior colleagues who’ve never had a when they fall on a weekend. In 2010 and 2011, both were bill drawn. -

Agenda by the Treasury: Agenda and Attendees, Future of Work Tripartite

The Treasury Future of Work Tripartite Forum Information Release Document April 2019 This document has been proactively released by the Treasury on the Treasury website at https://treasury.govt.nz/publications/information-release/future-of-work-tripartite Information Withheld Some parts of this information release would not be appropriate to release and, if requested, would be withheld under the Official Information Act 1982 (the Act). Where this is the case, the relevant sections of the Act that would apply have been identified. Where information has been withheld, no public interest has been identified that would outweigh the reasons for withholding it. Key to sections of the Act under which information has been withheld: [1] 9(2)(a) - to protect the privacy of natural persons, including deceased people [2] 9(2)(k) - to prevent the disclosure of official information for improper gain or improper advantage Where information has been withheld, a numbered reference to the applicable section of the Act has been made, as listed above. For example, a [2] appearing where information has been withheld in a release document refers to section 9(2)(k). Copyright and Licensing Cabinet material and advice to Ministers from the Treasury and other public service departments are © Crown copyright but are licensed for re-use under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) [https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/]. For material created by other parties, copyright is held by them and they must be consulted on the licensing terms that they apply to their material. Accessibility The Treasury can provide an alternate HTML version of this material if requested. -

Friday, 23 November 2012 Office of the Auditor General Level 2, State

Friday, 23 November 2012 Office of the Auditor General Level 2, State Services Commission Building 100 Molesworth Street Thorndon, Wellington 6140 By email ([email protected]) Dear Ms Provost, I am writing to request under s18 of the Public Audit Act 2001 that you conduct an urgent investigation into the tendering and decision-making processes that Kiwirail has used to procure rail wagons in the last two years. I also ask that you investigate the extent and appropriateness of political involvement and interference in tendering decisions made by the Kiwirail Board, which has blocked proposals from Hillside and Kiwirail management for rail carriages to be built at the Hillside Workshops in Dunedin. This letter follows up on a previous request dated August 7 2012 that you investigate the adequacy of evaluations for the contracts entered into between KiwiRail and China North Rail. It has been three months since I last wrote to you and since then a further 90 workers from Hillside have been laid off. The Hillside Foundry has been sold to a private buyer, which will employ just 18 staff and a skeleton Kiwirail staff will man the heavy lifting equipment that will be kept on the Hillside site. This once proud manufacturing and maintenance workshop has been brought to its knees by deliberate decisions of the Kiwirail Board and shareholding Ministers to block on-going contract work. The rationale for this has been an insistence on a lowest cost approach to tendering and the belief that Kiwirail no longer needs a rail manufacturing facility in the South Island. -

Reports of Select Committees on the 2018/19 Annual Reviews Of

I.20E Reports of select committees on the 2018/19 annual reviews of Government departments, Offices of Parliament, Crown entities, public organisations, and State enterprises Volume 2 Health Sector Justice Sector Māori, Other Populations and Cultural Sector Primary Sector Social Development and Housing Sector Fifty-second Parliament April 2020 Presented to the House of Representatives I.20E Contents Crown entity/public Select Committee Date presented Page organisation/State enterprise Financial Statements of the Finance and Expenditure 19 Mar 2020 13 Government of New Zealand for the year ended 30 June 2019 Economic Development and Infrastructure Sector Accident Compensation Education and Workforce Not yet reported Corporation Accreditation Council Economic Development, 27 Mar 2020 24 Science and Innovation AgResearch Limited Economic Development, 10 Mar 2020 25 Science and Innovation Air New Zealand Limited Transport and Infrastructure 25 Mar 2020 31 Airways Corporation of New Transport and Infrastructure 24 Mar 2020 38 Zealand Limited Callaghan Innovation Economic Development, 26 Mar 2020 39 Science and Innovation City Rail Link Limited Transport and Infrastructure 25 Mar 2020 47 Civil Aviation Authority of New Transport and Infrastructure 26 Mar 2020 54 Zealand Commerce Commission Economic Development, 27 Mar 2020 60 Science and Innovation Crown Infrastructure Partners Transport and Infrastructure 31 Mar 2020 68 Limited Earthquake Commission Governance and 13 Mar 2020 74 Administration Electricity Authority Transport and Infrastructure -

Free and Frank Advice

Volume 14 – Issue 2 – May 2018 Free and Frank Advice and the Official Information Act: balancing competing principles of good government Andrew Kibblewhite and Peter Boshier A New Approach to Environmental 3 Valuation for New Zealand Grease or Sand in the Wheels of Democracy? Peter Clough, Susan M. Chilton, The market for lobbying in New Zealand Michael W. Jones-Lee and Hugh R.T. Metcalf 50 Thomas Anderson and Simon Chapple 10 Delivering on Outcomes: the experience The Ardern Government’s Foreign of Ma-ori health service providers Policy Challenges Heather Gifford, Lesley Batten, Amohia Boulton, Robert Ayson 18 Melissa Cragg and Lynley Cvitanovic 58 Change and Resilience in New Zealand Aid Cold New Zealand Council Housing under Minister McCully Getting an Upgrade Jo Spratt and Terence Wood 25 Lara Rangiwhetu, Nevil Pierse, Helen Viggers and Reversing the Degradation of New Zealand’s Philippa Howden-Chapman 65 Environment through Greater Government ‘Unfair and discriminatory’: which regions Transparency and Accountability does New Zealand take refugees from and why? Murray Petrie 32 Murdoch Stephens 74 Funding Climate Change Adaptation: ICTs as an Antidote to Hardship and the case for a new policy framework Inequality: implications for New Zealand Jonathan Boston and Judy Lawrence 40 Catherine Cotter 80 Editorial – Free and Frank Advice and the Official Information Act This issue of Policy Quarterly leads with an important becomes known early in the process that they are under co-authored article on the challenge of balancing two active consideration. Volume 14 – Issue 2 – May 2018 of the fundamental constitutional principles embodied In short, ‘speaking truth to power’, while in the Official Information Act (OIA). -

Request for Information from Dpmcs OIA Tracking System, Including

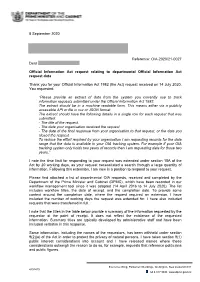

8 September 2020 Reference: OIA-2020/21-0027 Dear Official Information Act request relating to departmental Official Information Act request data Thank you for your Official Information Act 1982 (the Act) request received on 14 July 2020. You requested: “Please provide an extract of data from the system you currently use to track information requests submitted under the Official Information Act 1982. The extract should be in a machine readable form. This means either via a publicly accessible API or file in csv or JSON format. The extract should have the following details in a single row for each request that was submitted: - The title of the request. - The date your organisation received the request - The date of the final response from your organisation to that request, or the date you closed the request To reduce the effort required by your organisation I am requesting records for the date range that the data is available in your OIA tracking system. For example if your OIA tracking system only holds two years of records then I am requesting data for those two years.” I note the time limit for responding to your request was extended under section 15A of the Act by 20 working days, as your request necessitated a search through a large quantity of information. Following this extension, I am now in a position to respond to your request. Please find attached a list of departmental OIA requests, received and completed by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (DPMC), which have been recorded in our workflow management tool since it was adopted (14 April 2016 to 14 July 2020). -

Cabinet External Relations and Security Committee Minute Of

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet National Cyber Policy Office Proactive Release April 2018 The document below is released by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet relating to the refresh of New Zealand’s Cyber Security Strategy and Action Plan. Some parts of this document would not be appropriate to release and, if requested, would be withheld under the Official Information Act 1982 (the Act). Where this is the case, the relevant sections of the Act that would apply have been identified. Date: March 2018 Title: ERS Minute Refresh of New Zealand’s Cyber Security Strategy and Action Plan. Information withheld with relevant section(s) of the Act: Part of Recommendation 8.4 s 6(a) – security or defence of New Zealand. Released by the Minister of Broadcasting, Communications and Digital Media RESTRICTED ERS-18-MIN-0004 Cabinet External Relations and Security Committee Minute of Decision This document contains information for the New Zealand Cabinet. It must be treated in confidence and handled in accordance with any security classification, or other endorsement. The information can only be released, including under the Official Information Act 1982, by persons with the appropriate authority. Refresh of New Zealand's Cyber Security Strategy and Action Plan Portfolio Broadcasting, Communications and Digital Media On 27 March 2018, the Cabinet External Relations and Security Committee: 1 noted that on 3 November 2015, the previous government approved the New Zealand Cyber Security Strategy, the supporting Action Plan, and