Heroes Behind the Silver Screen Ever Since the Camera and Light-Sensitive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9780367508234 Text.Pdf

Development of the Global Film Industry The global film industry has witnessed significant transformations in the past few years. Regions outside the USA have begun to prosper while non-traditional produc- tion companies such as Netflix have assumed a larger market share and online movies adapted from literature have continued to gain in popularity. How have these trends shaped the global film industry? This book answers this question by analyzing an increasingly globalized business through a global lens. Development of the Global Film Industry examines the recent history and current state of the business in all parts of the world. While many existing studies focus on the internal workings of the industry, such as production, distribution and screening, this study takes a “big picture” view, encompassing the transnational integration of the cultural and entertainment industry as a whole, and pays more attention to the coordinated develop- ment of the film industry in the light of influence from literature, television, animation, games and other sectors. This volume is a critical reference for students, scholars and the public to help them understand the major trends facing the global film industry in today’s world. Qiao Li is Associate Professor at Taylor’s University, Selangor, Malaysia, and Visiting Professor at the Université Paris 1 Panthéon- Sorbonne. He has a PhD in Film Studies from the University of Gloucestershire, UK, with expertise in Chinese- language cinema. He is a PhD supervisor, a film festival jury member, and an enthusiast of digital filmmaking with award- winning short films. He is the editor ofMigration and Memory: Arts and Cinemas of the Chinese Diaspora (Maison des Sciences et de l’Homme du Pacifique, 2019). -

IMAX CHINA HOLDING, INC. (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with Limited Liability) (Stock Code: 1970)

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. IMAX CHINA HOLDING, INC. (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) (Stock Code: 1970) BUSINESS UPDATE WANDA CINEMA LINE CORPORATION LIMITED AGREES TO ADD 150 IMAX THEATRES The board of directors of IMAX China Holding, Inc. (the “Company”) announces that the Company (through its subsidiaries) has entered into an agreement (“Installation Agreement”) with Wanda Cinema Line Corporation Limited (“Wanda Cinema”). Under the Installation Agreement, 150 IMAX theatres will be built throughout China over six years, starting next year. With the Installation Agreement, the Company’s total number of theatre signings year to date has reached 229 in China and the total backlog will increase nearly 60 percent. The Installation Agreement is in addition to an agreement entered into between the Company and Wanda Cinema in 2013 (“Previous Installation Agreement”). Under the Previous Installation Agreement, Wanda Cinema committed to deploy 120 new IMAX theatres by 2020. The key commercial terms of the Installation Agreement are substantially similar to those under the Previous Installation Agreement. The Company made a press release today regarding the Installation Agreement. For -

Warriors As the Feminised Other

Warriors as the Feminised Other The study of male heroes in Chinese action cinema from 2000 to 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chinese Studies at the University of Canterbury by Yunxiang Chen University of Canterbury 2011 i Abstract ―Flowery boys‖ (花样少年) – when this phrase is applied to attractive young men it is now often considered as a compliment. This research sets out to study the feminisation phenomena in the representation of warriors in Chinese language films from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Mainland China made in the first decade of the new millennium (2000-2009), as these three regions are now often packaged together as a pan-unity of the Chinese cultural realm. The foci of this study are on the investigations of the warriors as the feminised Other from two aspects: their bodies as spectacles and the manifestation of feminine characteristics in the male warriors. This study aims to detect what lies underneath the beautiful masquerade of the warriors as the Other through comprehensive analyses of the representations of feminised warriors and comparison with their female counterparts. It aims to test the hypothesis that gender identities are inventory categories transformed by and with changing historical context. Simultaneously, it is a project to study how Chinese traditional values and postmodern metrosexual culture interacted to formulate Chinese contemporary masculinity. It is also a project to search for a cultural nationalism presented in these films with the examination of gender politics hidden in these feminisation phenomena. With Laura Mulvey‘s theory of the gaze as a starting point, this research reconsiders the power relationship between the viewing subject and the spectacle to study the possibility of multiple gaze as well as the power of spectacle. -

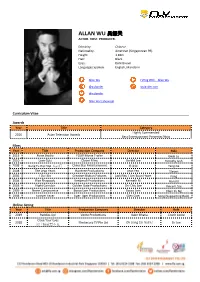

Allan Wu 吴振天 Actor

ALLAN WU 吴振天 ACTOR. HOST. PRODUCER. Ethnicity: Chinese Nationality: American (Singaporean PR) Height: 1.83m Hair: Black Eyes: Dark Brown Languages Spoken: English, Mandarin Allan Wu FLYing With... Allan Wu @wulander wulander.com @wulander Allan Wu's Showreel Curriculum Vitae Awards Year Title Category Highly Commended 2016 Asian Television Awards Best Entertainment Presenter/Host Films Year Title Production Company Director Role 2015 Poise Studio FOUR Movie Trailer Gwai Lo 2010 Love Cuts Clover Films Gerald Lee Timothy Goh 2008 Kung Fu Hip Hop 精武门 China Star Entertainment 傅华阳 Tang Ge 2008 The Leap Years Raintree Productions Jean Yeo Steven 2005 I Do I Do Creative Motion Pictures Jack Neo / Lim Boon Hwee Feng 2004 Rice Rhapsody Kenberoli Productions Kenneth Bi Ronald 2003 Night Corridor Golden Gate Productions Chi-Chiu Lee Vincent Sze 1999 Never Compromise Bosco Lam Productions Bosco Lam Chun Yu Ng 1998 Forever Fever Tiger Tiger Productions Glen Goei Seng (Supporting Role) Online Acting Year Title Production Company Director Role 2019 Paddles Up! Verite Productions Kabir Bhatia Coach Leslie Close Your Eyes 2018 Mediacorp TV Pte Ltd Oh Liang Cai 胡凉财 Dr Joe 闭上眼就看不见 Television Actor Year Title Production Company Director Role 2019 CLIF 5 Mediacorp TV Pte Ltd Oh Liang Cai Alexis 2018 Divided 分裂 Mediacorp TV Pte Ltd Lee Thean-jeen Inspector Wu Wenjie 2014 Mata Mata Season 2 MediaCorp TV Singapore Pte Ltd Alan Leong 2014 First Gear House Films Lead 2006 House Of Joy Mediacorp Studios Pte Ltd 罗温温 Zheng Sanji 2006 Xing Jing Er Ren Zhu Mediacorp -

Independent Cinema in the Chinese Film Industry

Independent cinema in the Chinese film industry Tingting Song A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Creative Industries Queensland University of Technology 2010 Abstract Chinese independent cinema has developed for more than twenty years. Two sorts of independent cinema exist in China. One is underground cinema, which is produced without official approvals and cannot be circulated in China, and the other are the films which are legally produced by small private film companies and circulated in the domestic film market. This sort of ‘within-system’ independent cinema has played a significant role in the development of Chinese cinema in terms of culture, economics and ideology. In contrast to the amount of comment on underground filmmaking in China, the significance of ‘within-system’ independent cinema has been underestimated by most scholars. This thesis is a study of how political management has determined the development of Chinese independent cinema and how Chinese independent cinema has developed during its various historical trajectories. This study takes media economics as the research approach, and its major methods utilise archive analysis and interviews. The thesis begins with a general review of the definition and business of American independent cinema. Then, after a literature review of Chinese independent cinema, it identifies significant gaps in previous studies and reviews issues of traditional definition and suggests a new definition. i After several case studies on the changes in the most famous Chinese directors’ careers, the thesis shows that state studios and private film companies are two essential domestic backers for filmmaking in China. -

MADE in HOLLYWOOD, CENSORED by BEIJING the U.S

MADE IN HOLLYWOOD, CENSORED BY BEIJING The U.S. Film Industry and Chinese Government Influence Made in Hollywood, Censored by Beijing: The U.S. Film Industry and Chinese Government Influence 1 MADE IN HOLLYWOOD, CENSORED BY BEIJING The U.S. Film Industry and Chinese Government Influence TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY I. INTRODUCTION 1 REPORT METHODOLOGY 5 PART I: HOW (AND WHY) BEIJING IS 6 ABLE TO INFLUENCE HOLLYWOOD PART II: THE WAY THIS INFLUENCE PLAYS OUT 20 PART III: ENTERING THE CHINESE MARKET 33 PART IV: LOOKING TOWARD SOLUTIONS 43 RECOMMENDATIONS 47 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 53 ENDNOTES 54 Made in Hollywood, Censored by Beijing: The U.S. Film Industry and Chinese Government Influence MADE IN HOLLYWOOD, CENSORED BY BEIJING EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ade in Hollywood, Censored by Beijing system is inconsistent with international norms of Mdescribes the ways in which the Chinese artistic freedom. government and its ruling Chinese Communist There are countless stories to be told about China, Party successfully influence Hollywood films, and those that are non-controversial from Beijing’s warns how this type of influence has increasingly perspective are no less valid. But there are also become normalized in Hollywood, and explains stories to be told about the ongoing crimes against the implications of this influence on freedom of humanity in Xinjiang, the ongoing struggle of Tibetans expression and on the types of stories that global to maintain their language and culture in the face of audiences are exposed to on the big screen. both societal changes and government policy, the Hollywood is one of the world’s most significant prodemocracy movement in Hong Kong, and honest, storytelling centers, a cinematic powerhouse whose everyday stories about how government policies movies are watched by millions across the globe. -

Corporate Profile

Corporate Profile! 2018 Fast Growing ! F&B Distributor! Copyright Provenance®distributions 2 Who We Are! Provenance® Distributions Pte Ltd is a fast growing company that imports and distributes fast-moving food & beverages (F&B) in Singapore, Hong Kong & Macau. We also re-export F&B to other Asian markets. The South China Morning Post — Asia’s most widely read English newspaper based in Hong Kong — featured us as ”A Rising Star in Asia.” (August 9, 2017) & The Straits Times — Singapore’s leading newspaper — also featured us on Singaporean brand successes in Hong Kong (Sep 9, 2018). We have an extensive B2B distribution network — covering 1,700+ locations — and distribute global brands such as S&W fruit juices and leading Singaporean brands such as The Golden Duck. We are an Official Partner of MICHELIN Guide for their events in the region. Through our strong marketing expertise, we run impactful marketing campaigns which generate brand awareness and sales. We are also sales & CRM experts with a large database of B2B purchaser contacts. Our vision is to become a leading distributor in Asia. Copyright Provenance®distributions 3 Rising Star in Asia! *As reported in the South China Morning Post, Business Section, 9th Aug 2017 Copyright Provenance®distributions 4 Freight Sales Marketing Suite of Services! Delivery Copyright Provenance®distributions Warehousing Orders Merchandising Receivables 5 Our Offices! China (Shenzhen) (In 2019) Singapore HQ Hong Kong Macau 318 Tanglin Rd Two IFC Praia Grand Copyright Provenance®distributions 6 Featured in -

Remaking Chinese Cinema: Through the Prism of Shanghai, Hong Kong

Remaking Chinese Cinema Through the Prism of Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Hollywood Yiman Wang © 2013 University of Hawai‘i Press All rights reserved First published in the United States of America by University of Hawai‘i Press Published for distribution in Australia, Southeast and East Asia by: Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org ISBN 978-988-8139-16-3 (Paperback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Designed by University of Hawai‘i Production Department Printed and bound by Kings Time Printing Press Ltd. in Hong Kong, China Contents Acknowledgments | xi Introduction | 1 1. The Goddess: Tracking the “Unknown Woman” from Hollywood through Shanghai to Hong Kong | 18 2. Family Resemblance, Class Conflicts: Re-version of the Sisterhood Singsong Drama | 48 3. The Love Parade Goes On: “Western-Costume Cantonese Opera Film” and the Foreignizing Remake | 82 4. Mr. Phantom Goes to the East: History and Its Afterlife from Hollywood to Shanghai and Hong Kong | 113 Conclusion: Mr. Undercover Goes Global | 143 Notes | 165 Bibliography | 191 Filmography | 207 Index | 211 ix CHAPTER 1 The Goddess Tracking the “Unknown Woman” from Hollywood through Shanghai to Hong Kong Maternal melodramas featuring self-sacrificial mothers abound in the history of world cinema. From classic Hollywood women’s films to Lars von Trier’s new-millennium musical drama Dancer in the Dark (2000), the mother figure works tirelessly for her child only to eventually withdraw herself from the child’s life in order to secure a prosperous future for him or her.1 In this chap- ter, I trace the Shanghai and Hong Kong remaking of an exemplary Hollywood maternal melodrama, Stella Dallas, in the 1930s. -

Humour in Chinese Life and Culture Resistance and Control in Modern Times

Humour in Chinese Life and Culture Resistance and Control in Modern Times Edited by Jessica Milner Davis and Jocelyn Chey A Companion Volume to H umour in Chinese Life and Letters: Classical and Traditional Approaches Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Hong Kong University Press 2013 ISBN 978-988-8139-23-1 (Hardback) ISBN 978-988-8139-24-8 (Paperback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Condor Production Limited, Hong Kong, China Contents List of illustrations and tables vii Contributors xi Editors’ note xix Preface xxi 1. Humour and its cultural context: Introduction and overview 1 Jessica Milner Davis 2. The phantom of the clock: Laughter and the time of life in the 23 writings of Qian Zhongshu and his contemporaries Diran John Sohigian 3. Unwarranted attention: The image of Japan in twentieth-century 47 Chinese humour Barak Kushner 4 Chinese cartoons and humour: The views of fi rst- and second- 81 generation cartoonists John A. Lent and Xu Ying 5. “Love you to the bone” and other songs: Humour and rusheng 103 rhymes in early Cantopop Marjorie K. M. Chan and Jocelyn Chey 6. -

HU Die Hú Dié 胡 蝶 1907–1989 Film Actress

◀ Household Responsibility System Comprehensive index starts in volume 5, page 2667. HU Die Hú Dié 胡 蝶 1907–1989 Film actress “Butterfly” Hu was the most famous Chinese (Meng Jiangnü, Madame White Snake, Zhu Yingtai, all actress of the silent and early sound era. Like of which are exemplary though “doomed” lovers in clas- many contemporaries, she performed under a sical Chinese oral tradition and fiction). In 1928 she par- stage name, which followed her throughout a layed this success into a high-paying contract with the career that spanned four decades. Once an offi- cial representative of China’s film industry un- Hu Die (1907– 1989). “Butterfly,” as she was known der the Nationalist Party, she founded her own to her adoring fans, reached won great acclaim for production company before retiring in 1967. playing a pair of estranged twins.. nown during the 1930s as China’s “Film Queen,” “Butterfly” Hu’s personal name was Ruihua and her father a high-ranking customs inspector for the Beijing-Fengtian Railway. Moving with her family from Shanghai to numerous cities in northern China al- lowed Hu to acquire fluency in several Chinese dialects. Although a film actress from 1925 onward, these linguistic abilities proved extremely valuable in aiding Hu to suc- cessfully make the transition from silent films to “talkies.” She starred in the Shanghai film industry’s first partial- sound production (the film was recorded with a complete soundtrack, but this was played back on a separate disk which accompanied the feature), The Singing Girl Red Pe- ony (1931), which also made her a figure in the burgeoning world of mass-produced popular music. -

C Ntentasia 19 Sept-2 Oct 2016 19 September-2 October 2016 Page 2

19 September- 2 October 2016 ! s r a ye 2 0 C 016 g 1 NTENT - Celebratin www.contentasia.tv l www.contentasiasummit.com APOS l Tech Turner’s Tuzki enters China’s movie space debuts in China Feature film under way with Tencent Pictures MAIN COLOR PALETTE 10 GRADIENT BG GRADIENT R: 190 G: 214 B: 48 Focus onR: 0 tech’sG: 0 B: 0 role in Take the green and the blue Take the green and the blue C: 30 M: 0 Y: 100 K: 0 C: 75 M: 68 Y: 67 K: 90 from the main palette. from the main palette. Opacity: 100% Opacity: 50% R: 0 G: 80 B: 255 unlockingR: 138 G: 140value B: 143 from Blending Mode: Normal Blending Mode: Hue C: 84 M: 68 Y: 0 K: 0 C: 49 M: 39 Y: 38 K: 3 consumer eyeballs/wallets Media Partners Asia (MPA) debuts APOS l Tech on Tuesday evening, setting hard-core tech/broadband/distribution conversations against the backdrop of one of China’s most scenic locations. MPA says media and telecom opera- tors are “at a critical crossroads amidst changes in CPE technology, the evolu- tion of broadband, technology con- solidation and the emergence of onine video”. The question, says executive director Vivek Couto, “is how operators are gear- ing to address these challenges with new and existing products”. The rest of the story is on page 4 Tuzki LeSports, NBA in Turner Asia Pacific has entered mainland centres. HK, Macau tie-up China’s movie rush with a feature film The MoU was announced out of Beijing based on the 10-year-old Tuzki emoticon. -

Negotiating Transnational Collaborations with the Chinese Film Industry

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 2017+ University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2019 Negotiating Transnational Collaborations with the Chinese Film Industry Kai Ruo Soh University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses1 University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Soh, Kai Ruo, Negotiating Transnational Collaborations with the Chinese Film Industry, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of the Arts, English and Media, University of Wollongong, 2019.