Why Evidence Matters to Dr Mark Porter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geschenken 10-03-2017.Pdf

Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal Kamerlid Geschenk Datum Agema, M. (PVV) - Ontvangen van De Landelijke Huisartsen Vereniging 19-5-2010 na een debat op 19 mei 2010 een thermometer en een bloeddrukmeter - Ontvangen van Koninklijke Horeca Nederland na het 18-5-2010 debat in Dudok op 18 mei 2010 2 cadeaubonnen à €100,-- per stuk van Alliance Gastronomique. - Ontvangen van Boom uitgevers Amsterdam drie 30-9-2008 boeken: Montesquieu, over de geest van de wetten (waarde €64,50); Mill over de vrijheid (waarde €18,50) en Pascal Bruckner, Tirannie van het berouw (€23,90), Totale waarde €106,90. Amhaouch, M. (CDA) - Geen 14-1-2016 Geschenken ontvangen door de leden 1 Kamerlid Geschenk Datum Arib, K. (PvdA) - Ontvangen van de heer Peumans, voorzitter van het 10-1-2017 Vlaams Parlement, het boek ‘A portrait of the Ardennes’ en prenten van Vermeersch. De waarde is onbekend. - Ontvangen van de heer Bracke, voorzitter van het 10-1-2017 Belgische federale parlement, een sjaal. De waarde is onbekend. - Ontvangen van de heer André Antoine, voorzitter van 10-1-2017 het Waals Parlement, een doos chocola. De waarde is onbekend. - Ontvangen van Helma Lodders het boek 'Power to 22-11-2016 the pieper'. De waarde is onbekend. - Ontvangen van Monique Bramsen het boek ‘van 16-11-2016 fractie-assistant tot minister president’. De waarde is onbekend. - Ontvangen van Diederick Slijkerman het boek ‘het 14-11-2016 geheim van de ministeriële verantwoordelijkheid’. De waarde is onbekend. - Ontvangen van het Rijksmuseum een boekenbon ter 29-10-2016 waarde van €50,-. - Ontvangen het boek 'F*ck die onzekerheid' van drs. -

ANW in NVOX 25 Recente Artikelen Over Vragen Bij Natuurwetenschappen in De Samenleving

oktober 2012 ANW in NVOX 25 recente artikelen over vragen bij natuurwetenschappen in de samenleving Voor docenten in Vlaanderen geldt een Hoe weet je of iets waar is ? eenmalig aanbod voor een abonnement op NVOX. Prijs € 35,00 per jaar. Mag alles wat kan ? Opgeven bij Waar komt wetenschap vandaan ? NVON-ledenadministratie t.a.v. mevrouw H. Tangenberg Hoe gebruik je kennis ? Stationsweg 44 NL7941HE Meppel, Nederland Hoe ontwikkelt wetenschap ? Email: [email protected] Hoe weet je of iets waar is? Deze hamvraag van het vak anw is en blijft iedere keer weer actueel. NVOX publiceerde recent artikelen waarin deze vraag centraal staat. Ook rare verhalen kunnen inspireren voor goede anw-lessen. Een paar voorbeelden voor gebruik in de klas. Arnoud Pollmann / redactie anw Het prachtvak anw mag op dit moment wel van z’n sokkel gevallen, niet?” Ik dan een ondergeschoven kindje zijn: de dacht: wat bedoelt hij toch? Even schrik- argumenten waarom er twintig jaar gele- ken en toen wist ik het. De publiciteit den zo enorm veel energie in is gesto- over neutrino’s die sneller zouden gaan ken, die staan nog paalvast boven water. dan het licht, daar reageerde hij op. Naar Scientific Literacy blijft een noodzaak verluidt, waren hier de gulzige media voor iedere Nederlander, treurig dat de met hun voortdurende primeurtjesjacht huidige minister van onderwijs dit niet weer de boosdoeners. Maar weer een ziet. mooie kans voor de anw-les: laat leerlin- gen uitzoeken waar de schoen wringt, “Er zijn mensen die geloven in de regu- door interviews en debat. liere geneeskunde, en er zijn mensen die zweren bij homeopathie.” Zo begint Pseudowetenschappen het tweede artikel van Wouter Schuring In NVOX, februari 2010 schreef Henny over deze twee thema’s in NVOX 8, resp. -

Healing En 'Alternatief' Genezen

Healing en ‘alternatief ’ genezen HEALING EN Peter Jan Margry ‘ALTERNATIEF’ een culturele diagnose GENEZEN Amsterdam University Press Afbeelding omslag: Twee vrouwenhanden en blauwe elektromagnetische ‘healing energy’, normaal alleen te zien door hen die aura's waarnemen. Foto N. Zalewski. Ontwerp omslag: Xpair Ontwerp binnenwerk: Sander Pinkse Boekproductie, Amsterdam ISBN 978 94 6298 789 0 e-ISBN 978 90 4853 983 3 (pdf) NUR 681 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/nl) Meertens Instituut (KNAW) / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2018 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). De uitgeverij heeft ernaar gestreefd alle copyrights van in deze uitgave opgenomen illustraties te achterhalen. Aan hen die desondanks menen alsnog rechten te kunnen doen gelden, wordt verzocht contact op te nemen met Amsterdam University Press. Inhoud 1 Vooraf 7 2 Waar hebben we het over: enkele begrippen 10 3 Enig verleden: kruidenmengers en magnetiseurs 39 4 Wat houdt het nu zoal in: ‘energy healing’ & de ‘healthy body’ 58 5 De Meertens-vragenlijst Alternatieve Geneeswijzen 92 6 Wat moeten we ermee? 115 Verantwoording 120 Noten 121 Literatuur 136 1 Vooraf ‘Ik ben benieuwd wat u beweegt om als Meertens Instituut aan dergelijk onderzoek uw medewerking te verlenen: wat is de relatie tussen uw werk tot die van alternatieve behandelingswijzen?’ Deze terechte vraag van een respondent kwam in 2016 bij het Meertens Instituut binnen nadat bekend was geworden dat wij het veld van alternatieve geneeswijzen nader wilden verkennen. -

And Folk Medicine in Dutch Historiography

Medical History, 1999, 43: 359-375 Shaping the Medical Market: On the Construction of Quackery and Folk Medicine in Dutch Historiography FRANK HUISMAN* It has been stated many times: traditionally, medical history was written by, for and about doctors, telling the story of unilinear scientific progress. Positivism tended to look at the history of medicine as a process of linear progress from religion through metaphysics to science, in which mankind was liberated from superstition and irrationality. This view was confirmed by the Weberian notion of a "disenchantment" of the world: in the course of the last few centuries, the influence of magic and animism was seen as having declined. In the field of medical thinking and medical practice, man was thought to have freed himself from the chains of superstition. Gradually, he had learned to relate to the world in rational terms; in the event of illness, academic doctors were the logical engineers of his body. However, the times of the grand stories are over, in general as well as in medical history. With non-physicians moving into the field, there has been a growing awareness of the constructed nature of medicine.1 Medical knowledge has come to be seen as functioning within a specific cultural context from which it derives its meaning.2 Today, illness is no longer considered to be a universal, ontological unit. Instead, the meaning of illness-as well as the response to it-is thought to be determined by factors of a social, economic, political and religious nature.3 The attraction of the old historical image lay in its simplicity. -

Margaret Mccartney: the Social Care System Has Become Inherently Unsafe

BMJ 2017;357:j2329 doi: 10.1136/bmj.j2329 (Published 2017 May 30) Page 1 of 2 Views and Reviews BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj.j2329 on 30 May 2017. Downloaded from VIEWS AND REVIEWS NO HOLDS BARRED Margaret McCartney: The social care system has become inherently unsafe Margaret McCartney general practitioner Glasgow Ellen Ash was an elderly woman with severe dementia, who with many time consuming assessments. The community team lived in Glasgow. She died in 2013 after she was smothered is dissolving, and our district nurses no longer work, long term, and her house was set on fire. Her son, Jeffrey, went to the police from the practice as part of our team but “horizontally,” across the next day to confess to both.1 He was her carer and seems to many. have been under immense stress. This may be “agile,” but it loses the longer term, soft knowledge Social care is under intense pressure but also scrutiny. Over the on which harder decisions are based. No basic record exists past few months this complex case has been discussed at wide between district nurses and GPs, social work, and care agencies http://www.bmj.com/ ranging, interdisciplinary meetings involving health and social to say who’s involved. I can alert social workers to concerns, care staff. In Scotland, social and health care are integrated in but what then? Everyone is working over capacity, in workplaces law. But in practice? not designed to ensure that professionals have the minimum In the months before her death Ash was admitted to hospital information to do the job safely. -

Covid-19: People Are Not Being Warned About Pitfalls of Mass Testing

NEWS BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj.n238 on 26 January 2021. Downloaded from The BMJ EXCLUSIVE Cite this as: BMJ 2021;372:n238 http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n238 Published: 26 January 2021 Covid-19: People are not being warned about pitfalls of mass testing Elisabeth Mahase Only a third of local authorities that are rolling out local authorities in communicating such public health lateral flow testing have made the test’s limitations messages. clear to the public—including that it does not pick However, Mike Gill, former regional director of public up all cases and that people testing negative could health for the South East region, highlighted that the still be infected, an investigation by The BMJ has government’s community testing guidance4 for local found. authorities did not make the limitations clear. A search of the websites of the 114 local authorities He said, “It is absolutely appropriate that local rolling out lateral flow testing1 found that 81 provided authorities shape the messaging surrounding testing information for the public on rapid covid-19 testing. to suit local circumstances and cultural groups, but Of these, nearly half (47%; 38) did not explain the all messaging should fulfil basic minimum standards. limitations of the tests or make it clear that people needed to continue following the restrictions or safety “Unfortunately, this range of approaches across the measures even if they tested negative, as they could country is predictable. The recently published still be infected. government guide to community testing,4 for all its length, is entirely silent on the issue of standards of Although 53% (43) did advise people to continue to messaging. -

Wetenschap Van Gene Zijde Geschiedenis Van De Nederlandse Parapsychologie in De Twintigste Eeuw

WETENSCHAP VAN GENE ZIJDE GESCHIEDENIS VAN DE NEDERLANDSE PARAPSYCHOLOGIE IN DE TWINTIGSTE EEUW SCIENCE FROM BEYOND HISTORY OF DUTCH PARAPSYCHOLOGY IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY (WITH A SUMMARY IN ENGLISH) PROEFSCHRIFT TER VERKRIJGING VAN DE GRAAD VAN DOCTOR AAN DE UNIVERSITEIT UTRECHT OP GEZAG VAN DE RECTOR MAGNIFICUS, PROF.DR. G.J. VAN DER ZWAAN, INGEVOLGE HET BESLUIT VAN HET COLLEGE VOOR PROMOTIES IN HET OPENBAAR TE VERDEDIGEN OP DONDERDAG 18 FEBRUARI 2016 DES MIDDAGS TE 4.15 UUR DOOR INGRID ELS KLOOSTERMAN GEBOREN OP 21 OKTOBER 1983 TE FRANEKER PROMOTOREN: PROF. DR. W. KOOPS PROF. DR. J. VIJSELAAR COPROMOTOR: DR. J. BOS INHOUD OVERZICHT INTERVIEWS EN ARCHIEVEN 8 1 INTRODUCTIE 11 2 DE NATUUR GOOCHELT NIET: POGINGEN TOT PSYCHISCH ONDERZOEK 1888-1914 EEN MISLUKTE SEANCE 41 POGINGEN TOT PSYCHISCH ONDERZOEK 45 FREDERIK VAN EEDEN ALS OVERTUIGD SPIRITIST 48 HENRI DE FREMERY ALS KRITISCH SPIRITIST 63 CONCLUSIES 80 3 VERBORGEN KRACHTEN: VERENIGINGEN VOOR PSYCHISCH ONDERZOEK 1915-1925 TELEPATHIE VAN TONEEL NAAR LABORATORIUM 83 VERENIGINGEN VOOR PSYCHISCH ONDERZOEK 86 EEN VERENIGING VOOR TOEGEPAST MAGNETISME 89 DE STUDIEVEREENIGING VOOR PSYCHICAL RESEARCH 101 CONCLUSIES 122 4 DE BOVENNATUUR IN DE PRAKTIJK: ACADEMISCHE VERBINTENISSEN 1928-1940 DE STRIJD OM DE PARAPSYCHOLOGIE 125 ACADEMISCHE VERBINTENISSEN 128 DE EERSTE PRIVAATDOCENTEN 131 WETENSCHAPPELIJK TIJDSCHRIFT EN LABORATORIUM 143 CONCLUSIES 161 5 EEN BIJZONDERE PERSOONLIJKHEID: ACADEMISCHE INBEDDING IN UTRECHT 1940-1959 EEN INTERNATIONALE CONFERENTIE 163 ACADEMISCHE INBEDDING IN UTRECHT 167 -

Joint Meeting of the All-Party Parliamentary Group for First Do No Harm and the British Medical Journal

Joint meeting of the All-Party Parliamentary Group for First Do No Harm and the British Medical Journal Venue and time 10:00am, Friday 21st May 2021 Via Zoom virtual conferencing Parliamentarians attending • Baroness Cumberlege, Co-Chair • Emma Hardy MP, Vice-Chair Panellists • Fiona Godlee, Editor-In-Chief, British Medical Journal • Kath Sansom, Sling the Mesh • Margaret McCartney, general practitioner, writer and broadcaster • Professor Neil Mortensen, President, Royal College of Surgeons • Professor Colin Melville, Medical Director and Director of Education and Standards, General Medical Council • Sir Cyril Chantler, Vice-Chair of the IMMDS Review Additional guests • Simon Whale, panel member, IMMDS Review • Dr Sonia Macleod, senior researcher to the IMMDS Review • Dr Chris van Tulleken, Infectious disease doctor, broadcaster and academic • Rebecca Coombes, Head of Journalism, British Medical Journal Apologies • The Rt Hon Jeremy Hunt MP, Co-Chair • Cat Smith MP, Vice-Chair • Dr Valerie Brasse, Secretary to the IMMDS Review Introduction Baroness Cumberlege began by welcoming fellow parliamentarians, patient group campaigners, her fellow panellists, members of the media and other attendees to the launch event. She also introduced the team from the Independent Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Review, who were on-screen: 1 • Sir Cyril Chantler • Simon Whale • Dr Sonia Macleod Baroness Cumberlege provided attendees with background to the joint meeting, referencing the work of the Independent Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Review, which she Chaired, and which published its report, First Do No Harm, last July. The report stated that transparency of payments made to clinicals needs to improve and it recommended (Recommendation 8) that the register of the General Medical Council should be expanded to include a list of financial and non-pecuniary interests for all doctors, as well a specialisms. -

Alternatieve Geneeswijzen

Alternatieve Geneeswijzen Nobelprijs 2015 geneeskunde voor dr. Tu, een triomf voor de Chinese geneeskunde? Het complementaire en al- ternatieve geneeswijzen (CAG) protocol; voor een verantwoorde toepassing in de reguliere zorg EPSA Autumn Assembly Malta Jaargang 103, nummer 2, januari 2016 Word lid van de KNMP De KNMP speelt een belangrijke rol bij het • Gratis éénmalig het Informatorium bewaken van de kwaliteit van het vak van Medicamentorum tijdens de studie. apotheker, ook op jouw universiteit. • Gratis éénmalig het FNA tijdens de Zo zetten wij ons in voor de erkenning van studie. het specialisme openbare farmacie. Jouw • Standaarden voor Zelfzorg tegen opleiding wordt afgestemd op de wensen een sterk gereduceerd tarief. en eisen vanuit het veld en op de toekomst. • Toegang tot alle informatie op www.knmp.nl, waaronder de De KNMP is dé vereniging die essentieel KNMP Leden- en Apothekenlijst. is bij de invulling en uitvoering van het • Gratis toegang tot de KNMP beroep van apotheker. Ook voor jou! Wetenschapsdag in het voorjaar en het KNMP Congres in het najaar. Wat krijg je ervoor? Voor e 37,50 per jaar ben je kandidaatlid van de KNMP. De voordelen van het KNMP Lid worden? kandidaatlidmaatschap op een rijtje: E-mail je gegevens naar [email protected], • Het Pharmaceutisch Weekblad, vakblad o.v.v. aanvraag kandidaat-lidmaatschap. voor apothekers, elke week op de mat. Meer weten: kijk op www.knmp.nl. Koninklijke Nederlandse Maatschappij ter bevordering der Pharmacie JANUARI 2016 Agenda K.N.P.S.V. 23/01 Januari AV der K.N.P.S.V. te Leiden 27/01 Specialisme Openbare U.P.S.V. -

Charges for Scoring Systems May Change Practice

PERSONAL VIEW Charges for scoring systems may change practice Much medical knowledge is copyrighted, but charges to reproduce clinical scoring criteria such as the Mini Mental State Examination may see them disappear from guidelines, writes Hugo Farne small but important change is number of titles—when previously the bulk quietly taking place in academic of article citations were accounted for by publishing, to the detriment of a few papers in the top journals10—and authors and readers alike. falling library budgets have been met with The National Institute rises in subscription charges in excess of Afor Health and Care Excellence (NICE) inflation (the “serials crisis”).11 Aggressively recommends using the Wells score to assess pursuing publishers who quote their content, patients with a suspected pulmonary particularly scoring systems that are often embolus, for example, and it recommends reproduced, can provide additional revenues the CHA2DS2-VASc score to identify which for journals. patients with atrial fibrillation are at high risk of stroke and should start prophylactic Intellectual property anticoagulation. However, if you wish It is only right that journals should seek to publish an article, book, smartphone to protect the intellectual property of their application, or website that reminds readers authors against plagiarism. However, scoring of these scoring systems, it will cost you systems were intended to be used as widely dearly—as much as $750 (£486; €690) goes as possible. By charging such high fees, these to the Annals of Internal Medicine for the Royalties for reproduction: room for improvement scoring systems will inevitably be less widely Wells score and $360 to the journal Chest read and used, much as articles incurring a for the CHA2DS2-VASc score (see table). -

Gps to Convene Crisis Summit

this week GPs to convene crisis summit The chair of the BMA’s General sustainability is in serious question, and Chaand Nagpaul said the Practitioners Committee has warned the the ability of GPs to continue with their current crisis in general government that the future sustainability current workload and current pressures practice “can no longer be ignored by politicians” of UK general practice is “in serious is unsustainable. This conference has question,” ahead of a crisis summit later been called because we are in a desperate this month. situation with regards to general practice.” Chaand Nagpaul said that the first Nagpaul added, “The conference is special meeting of local medical bringing to the fore an issue that can no committees (the statutory bodies that longer be ignored by politicians. But it represent GPs locally) in 13 years—due is also about ensuring clear action is to take place on 30 January—highlighted taken to enable general practice to get the severity of the current crisis in general back on its feet.” practice and would bring to the fore “an Peter Holden, a member of issue that can no longer be ignored by Derbyshire Local Medical Committee politicians.” and a former negotiator on the BMA The meeting has been organised by General Practitioners Committee, NEWS ONLINE the BMA in response to growing concern has proposed a motion warning the Wider group of among members of local medical government that industrial action • health professionals committees that rising demand from from GPs was “on the cards” unless should be located patients, stretched resources, and over- the government acted to support the in emergency regulation were harming the care of beleaguered primary care system. -

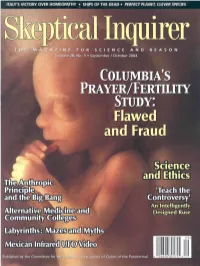

Flawed and Fraud

ITALY'S VICTORY OVER HOMEOPATHY • SHIPS OF THE DEAD • PERFECT PLANET, CLEVER SPECIES Volume 28; No. 5 • September / October 2004 COLUMBIA'S PRAYER/FERTILITY STUDY: Flawed and Fraud Science and Ethics Teach the Controversy1 An Intelligently Alternative Medicine and Designed Ruse Published by the Committee for the Scientific Investition of Claims ofis the o Paranormalf the Paranorma l THE COMMITTEE FOR THE SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION of Claims of the Paranormal AT THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY- TRANSNATIONAL (ADJACENT TO THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFAlO| AN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo Barry Karr, Executive Director Joe Nicked, Senior Research Fellow Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director FELLOWS James E. Alcock,* psychologist, York Univ., Toronto Thomas Gilovich, psychologist. Cornell Univ. Bill Nye. science educator and television host Nye Labs Jerry Andrus, magician and inventor, Albany, Henry Gordon, magician, columnist, Toronto James E. Oberg. science writer Oregon Saul Green, Ph.D., biochemist president of ZOL Irmgard Oepen, professor of medicine (retired). Marcia Angell. M.D., former editor-in-chief, New Consultants, New York, NY Marburg, Germany England Journal of Medicine Susan Haack, Cooper Senior Scholar in Arts Loren Pankratz, psychologist Oregon Health Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Kentucky and Sciences, prof, of philosophy, University Sciences Univ. Stephen Barrett, M.D.. psychiatrist, author, of Miami John Paulos, mathematician, Temple Univ. consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. C. E. M. Hansel, psychologist, Univ. of Wales Steven Pinker, cognitive scientist. MIT Willem Betz, professor of medicine, Univ. of David J.