Ray Bradbury's Independent Mind: an Inquiry Into Public Intellectualism”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stairway to Heaven? Geographies of the Space Elevator in Science Fiction

ISSN 2624-9081 • DOI 10.26034/roadsides-202000306 Stairway to Heaven? Geographies of the Space Elevator in Science Fiction Oliver Dunnett Outer space is often presented as a kind of universal global commons – a space for all humankind, against which the hopes and dreams of humanity have been projected. Yet, since the advent of spaceflight, it has become apparent that access to outer space has been limited, shaped and procured in certain ways. Geographical approaches to the study of outer space have started to interrogate the ways in which such inequalities have emerged and sustained themselves, across environmental, cultural and political registers. For example, recent studies have understood outer space as increasingly foreclosed by certain state and commercial actors (Beery 2012), have emphasised narratives of tropical difference in understanding geosynchronous equatorial satellite orbits (Dunnett 2019) and, more broadly, have conceptualised the Solar System as part of Earth’s environment (Degroot 2017). It is clear from this and related literature that various types of infrastructure have been a significant part of the uneven geographies of outer space, whether in terms of long-established spaceports (Redfield 2000), anticipatory infrastructures (Gorman 2009) or redundant space hardware orbiting Earth as debris (Klinger 2019). collection no. 003 • Infrastructure on/off Earth Roadsides Stairway to Heaven? 43 Having been the subject of speculation in both engineering and science-fictional discourses for many decades, the space elevator has more recently been promoted as a “revolutionary and efficient way to space for all humanity” (ISEC 2017). The concept involves a tether lowered from a position in geostationary orbit to a point on Earth’s equator, along which an elevator can ascend and arrive in orbit. -

Sigma-348.Pdf

Sigma The Newsletter of PARSEC - www.parsec-sff.org March, 2015 - No. 348 ing stable member of the community. I've been told President’s Capsule numerous times in the midst of some supposed The quality of being amusing solemn conversation, "Joe, this is no joking matter!" or comic... To me, joking matters are serious. Even though the or one of the four fluids of the hint of levity makes my status take quite a tumble to- body: blood, phlegm, yellow ward frivolous. bile or black bile. I look for humor where I can find it. In surprising Funny thing. I've been thinking and hidden places. In a turn of phrase. In an obscure by Joe Coluccio about humor lately. reference. I can often hear the writer smiling over And speculative fiction, of course. some small innocent paragraph of seeming lightness Some of you know I was a member of a comedy and fluff that may often sum up the meaning of the group that performed both on AM and FM radio and whole work. Certainly you have smiled at the con- at various venues around Pittsburgh. The group was cerns of the Puppeteers or the antics of Louis Wu, or called The Lackzoom Acidophilus Hour. Yes, there those of you with more daring, the instability of the is a story about the name. But really it was an homage Kzinti. There is nothing more funny, paranoid and to many of the old commercially sponsored schizophrenic than any of the works of Philip K. radio/television comedy and variety hours. -

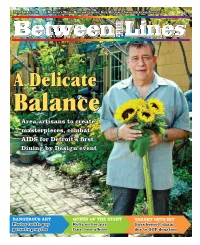

Area Artisans to Create Masterpieces, Combat AIDS for Detroit's First

PRIDESOURCE.COM MICHIGAN’S WEEKLY NEWS FOR LESBIANS, GAYS, BISEXUALS, TRANSGENDERS AND FRIENDS 1831 08.05.10 A Delicate Balance Area artisans to create masterpieces, combat AIDS for Detroit’s first Dining by Design event DANGEROUS ART QUEEN OF THE NIGHT TARGET GETS HIT Photos tackle gay Kelis on her gay Gays boycott chain parenting myths fans, new album due to GOP donation 2 Between The Lines • August 5, 2010 August 5, 2010 Vol. 1831 • Issue 673 Publishers Susan Horowitz Jan Stevenson EDITORIAL Editor in Chief Susan Horowitz Entertainment Editor Chris Azzopardi Associate News Editor Jessica Carreras Arts & Theater Editor 12 19 21 34 Donald V. Calamia Editorial Intern 13 NJ Supreme Court rejects 25 Curtain Calls Lucy Hough News same-sex marriage case Reviews of “The Last Night of Ballyhoo” and Contributing Writers Lawsuit filed over whether state’s civil union “Herstory Repeats Herself: A Trilogy in 3-D” Charles Alexander, Paul Berg, Wayne Besen, 5 Between Ourselves law provides equal treatment for gay couples D.A. Blackburn, Dave Brousseau, Tony O’Rourke-Quintana Michelle E. Brown, John Corvino, 26 Happenings Jack Fertig, Joan Hilty, Lisa Keen, Jim Larkin, Jason A. Michael, 14 International News Briefs Anthony Paull, Crystal Proxmire, 6 A Delicate Balance Gay weddings begin in Argentina Bob Roehr, Gregg Shapiro, Jody Valley, Beauty of art meets darkness of disease Rear View D’Anne Witkowski, Imani Williams at Detroit’s first Dining by Design HIV/AIDS Rex Wockner, Dan Woog fundraiser Opinions Contributing Photographer 28 Dear Jody Andrew -

The Collected Works of Ambrose Bierce

m ill iiiii;!: t!;:!iiii; PS Al V-ID BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF Henrg W, Sage 1891 B^^WiS _ i.i|j(i5 Cornell University Library PS 1097.A1 1909 V.10 The collected works of Ambrose Blerce. 3 1924 021 998 889 The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924021998889 THE COLLECTED WORKS OF AMBROSE BIERCE VOLUME X UIBI f\^^°\\\i COPYHIGHT, 1911, Br THE NEALE PUBLISHING COMPANY CONTENTS PAGE THE OPINIONATOR The Novel 17 On Literary Criticism 25 Stage Illusion 49 The Matter of Manner 57 On Reading New Books 65 Alphab£tes and Border Ruffians .... 69 To Train a Writer 75 As to Cartooning 79 The S. p. W 87 Portraits of Elderly Authors .... 95 Wit and Humor 98 Word Changes and Slang . ... 103 The Ravages of Shakspearitis .... 109 England's Laureate 113 Hall Caine on Hall Gaining . • "7 Visions of the Night . .... 132 THE REVIEWER Edwin Markham's Poems 137 "The Kreutzer Sonata" .... 149 Emma Frances Dawson 166 Marie Bashkirtseff 172 A Poet and His Poem 177 THE CONTROVERSIALIST An Insurrection of the Peasantry . 189 CONTENTS page Montagues and Capulets 209 A Dead Lion . 212 The Short Story 234 Who are Great? 249 Poetry and Verse 256 Thought and Feeling 274 THE' TIMOROUS REPORTER The Passing of Satire 2S1 Some Disadvantages of Genius 285 Our Sacrosanct Orthography . 299 The Author as an Opportunity 306 On Posthumous Renown . -

Teacher (Last Name) Title and Author of Book Brief Summary Secura the Hate You Give--Angie Thomas “Sixteen-Year-Old Star

Teacher Title and author Brief summary (Last of book Name) Secura The Hate You “Sixteen-year-old Starr Carter moves between two worlds: Give--Angie the poor neighborhood where she lives and the fancy Thomas suburban prep school she attends. The uneasy balance between these worlds is shattered when Starr witnesses the fatal shooting of her childhood best friend Khalil at the hands of a police officer. Khalil was unarmed.What everyone wants to know is: what really went down that night? And the only person alive who can answer that is Starr.” This book addresses controversial issues of interest to many adolescents and includes scenes and language that reflect mature content. Imbarus Out of the Dr. Aura Imbarus vividly details Christmas Day 1989, Transylvania when she, her parents and hundreds of shoppers drew Night--Aura sudden sniper fire as Romania descended into the Imbarus violence of a revolution that challenged one of the most draconian regimes in the Soviet bloc. Aura recalls a grisly execution that rocked the world and led to five harrowing days of bloody chaos as she and her family struggled to survive. The next day, Communist-controlled television released photos showing that dictator Nicolae Ceausescu and his wife had been assassinated-though many Romanians, the author included, believed the executions had been staged since Ceausescu was known for using stand-ins to pose for him. Nevertheless, Aura tries to convince herself that life post-revolution will be different, but little changes. On May 7, 1997, with two pieces of luggage and a powerful dream, Aura and her new husband flee to America. -

FAHRENHEIT 451 by Ray Bradbury This One, with Gratitude, Is for DON CONGDON

FAHRENHEIT 451 by Ray Bradbury This one, with gratitude, is for DON CONGDON. FAHRENHEIT 451: The temperature at which book-paper catches fire and burns PART I: THE HEARTH AND THE SALAMANDER IT WAS A PLEASURE TO BURN. IT was a special pleasure to see things eaten, to see things blackened and changed. With the brass nozzle in his fists, with this great python spitting its venomous kerosene upon the world, the blood pounded in his head, and his hands were the hands of some amazing conductor playing all the symphonies of blazing and burning to bring down the tatters and charcoal ruins of history. With his symbolic helmet numbered 451 on his stolid head, and his eyes all orange flame with the thought of what came next, he flicked the igniter and the house jumped up in a gorging fire that burned the evening sky red and yellow and black. He strode in a swarm of fireflies. He wanted above all, like the old joke, to shove a marshmallow on a stick in the furnace, while the flapping pigeon- winged books died on the porch and lawn of the house. While the books went up in sparkling whirls and blew away on a wind turned dark with burning. Montag grinned the fierce grin of all men singed and driven back by flame. He knew that when he returned to the firehouse, he might wink at himself, a minstrel man, Does% burntcorked, in the mirror. Later, going to sleep, he would feel the fiery smile still gripped by his Montag% face muscles, in the dark. -

Beaver News, 50(18)

astic from and arry abed March 30 1976 Voume No 18 were ams ite Council announces Leres John Linnell underi the tweIvehour Big goes will thIy courses nder By Elaine Maiperson By Lotsa Morals The Graduate Council has an- the full time to explore all Dr John Linnell Dean of the new schedule for 300 and ramifications of an idea College recently announced his %el to into effect at courses go Mr Stewart registrar com intentions to aid Dr Edward Gates College in the fall of 1976 President of the in his at- mented Im excited about the way College ath course will be offered once to Beavers the new plan opens up the schedule tempt improve security for of twelve single period We will certainly have fewer con system Beaver security is from to This flicts next year Fhe graduate average just average merely will the to plan help college students like to consolidate then average Dean Linnell commented efficient of more use But we have to take look at what class time by making fewer trips to assroom space and of faculty time we arc and where were and the campus The new schedule will going Under the new instructors make system attract more graduate students As decision based upon how it II be able to teach at least four will affect the see it the only problem will be the entire College corn- aduate courses over and above weathcr One snow closing will munity Lr normal load of three un block out month of classes Dean Linnell has de ided that yrgrduat courses Now well be radically hargrg Bcavcr Litsa Marlos senior English to teach seven courses each security -

Vanausdall on Duncan and Klooster, 'Phantoms of a Blood- Stained Period: the Complete Civil War Writings of Ambrose Bierce'

H-Indiana Vanausdall on Duncan and Klooster, 'Phantoms of a Blood- Stained Period: The Complete Civil War Writings of Ambrose Bierce' Review published on Thursday, August 1, 2002 Russell Duncan, David J. Klooster, eds. Phantoms of a Blood-Stained Period: The Complete Civil War Writings of Ambrose Bierce. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2002. xiv + 343 pp. $60.00 (cloth) ISBN 1-55849-327-1; $19.95 (paper), ISBN 978-1-55849-328-5. Reviewed by Jeanette Vanausdall (independent historian, Indianapolis)Published on H-Indiana (August, 2002) Writer as Witness Writer as Witness Phantoms of a Blood-Stained Period: The Complete Civil War Writings of Ambrose Bierce, edited by Russell Duncan and David J. Klooster, is a useful addition to the small assortment of Bierce collections available to students and scholars today. Bierce was perhaps the most significant American writer to have actually been a soldier throughout the war. For this reason alone he would be worth reading. But Bierce holds special interest for the student of the war because his work was so markedly different from most first-hand accounts, particularly the revisionist regimental histories that littered the literary landscape during the decades after the war. Rather than glorify the war and the soldiers who fought it, Bierce insisted upon exposing the bloodiness, brutality, stupidity, fear and cowardice to which he had been witness. Bierce genuinely deplored the war, but he also seemed to revel in his reputation as the foremost malcontent of his generation. Born in Meigs County, Ohio in 1842, Bierce's family was living in Indiana when the war broke out. -

By Jennifer M. Fogel a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

A MODERN FAMILY: THE PERFORMANCE OF “FAMILY” AND FAMILIALISM IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION SERIES by Jennifer M. Fogel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Regina Morantz-Sanchez Associate Professor Bambi L. Haggins, Arizona State University © Jennifer M. Fogel 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee – Dr. Susan J. Douglas, Dr. Bambi L. Haggins, and Dr. Regina Morantz-Sanchez, who each contributed their time, expertise, encouragement, and comments throughout this entire process. These women who have mentored and guided me for a number of years have my utmost respect for the work they continue to contribute to our field. I owe my deepest gratitude to my advisor Dr. Amanda D. Lotz, who patiently refused to accept anything but my best work, motivated me to be a better teacher and academic, praised my successes, and will forever remain a friend and mentor. Without her constructive criticism, brainstorming sessions, and matching appreciation for good television, I would have been lost to the wolves of academia. One does not make a journey like this alone, and it would be remiss of me not to express my humble thanks to my parents and sister, without whom seven long and lonely years would not have passed by so quickly. They were both my inspiration and staunchest supporters. Without their tireless encouragement, laughter, and nurturing this dissertation would not have been possible. -

Bomb Threat Suspect Found

Researcher receives science El Gallo de Oro lacks CMU students perform at contribution award • A4 drastic changes • A6 FringeNYC • B8 SCITECH FORUM PILLBOX thetartan.org @thetartan August 27, 2012 Volume 107, Issue 2 Carnegie Mellon’s student newspaper since 1906 Bomb Hunt Library gets new layout Wheels on bus to threat keep going round MADELYN GLYMOUR membership ratified it by a News Editor 10-to-one margin, and the suspect reason they ratified it by that The Port Authority an- margin was because of that nounced last Tuesday that the language.” found service reduction planned for Palonis pointed to Allegh- Sept. 2 would be postponed eny County Executive Rich JUSTIN MCGOWN until at least August 2013. Fitzgerald as another pivotal Staffwriter The postponement is the player in the agreement. result of a deal reached by “He really kept our nose The FBI officially in- the Port Authority, Allegh- to the grindstone throughout dicted Adam Stuart Busby eny County, Governor Tom this process,” Palonis said. on Aug. 22 for sending over Corbett’s office, and the Lo- “Rich is an advocate for trans- 40 threatening emails to the cal 85 Amalgamated Transit portation. I’ve dealt with a lot University of Pittsburgh last Union. Under the deal, Port of politicians through this year. Busby’s emails were Authority employees in the process, but Rich really wants part of a series of over 100 Local 85 union will undergo to see transportation grow.” bomb threats issued to Pitt a two-year pay freeze and According to the Pitts- throughout the spring se- increase the percentage of burgh Post-Gazette, Fitzger- mester. -

The Other in Science Fiction As a Problem for Social Theory 1

doi: 10.17323/1728-192x-2020-4-61-81 The Other in Science Fiction as a Problem for Social Theory 1 Vladimir Bystrov Doctor of Philosophical Sciences, Professor, Saint Petersburg University Address: Universitetskaya Nabereznaya, 7/9, Saint Petersburg, Russian Federation 199034 E-mail: [email protected] Vladimir Kamnev Doctor of Philosophical Sciences, Professor, Saint Petersburg University Address: Universitetskaya Nabereznaya, 7/9, Saint Petersburg, Russian Federation 199034 E-mail: [email protected] The paper discusses science fiction literature in its relation to some aspects of the socio- anthropological problem, such as the representation of the Other. Given the diversity of sci-fi genres, a researcher always deals either with the direct representation of the Other (a crea- ture different from an existing human being), or with its indirect, mediated form when the Other, in the original sense of this term, is revealed to the reader or viewer through the optics of some Other World. The article describes two modes of representing the Other by sci-fi literature, conventionally designated as scientist and anti-anthropic. Thescientist representa- tion constructs exclusively-rational premises for the relationship with the Other. Edmund Husserl’s concept of truth, which is the same for humans, non-humans, angels, and gods, can be considered as its historical and philosophical correlate. The anti-anthropic representa- tion, which is more attractive to sci-fi authors, has its origins in the experience of the “dis- enchantment” of the world characteristic of modern man, especially in the tragic feeling of incommensurability of a finite human existence and the infinity of the cosmic abysses. -

Zen in the Art of Writing – Ray Bradbury

A NOTE ABOUT THE AUTHOR Ray Bradbury has published some twenty-seven books—novels, stories, plays, essays, and poems—since his first story appeared when he was twenty years old. He began writing for the movies in 1952—with the script for his own Beast from 20,000 Fathoms. The next year he wrote the screenplays for It Came from Outer Space and Moby Dick. And in 1961 he wrote Orson Welles's narration for King of Kings. Films have been made of his "The Picasso Summer," The Illustrated Man, Fahrenheit 451, The Mar- tian Chronicles, and Something Wicked This Way Comes, and the short animated film Icarus Montgolfier Wright, based on his story of the history of flight, was nominated for an Academy Award. Since 1985 he has adapted his stories for "The Ray Bradbury Theater" on USA Cable television. ZEN IN THE ART OF WRITING RAY BRADBURY JOSHUA ODELL EDITIONS SANTA BARBARA 1996 Copyright © 1994 Ray Bradbury Enterprises. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Owing to limitations of space, acknowledgments to reprint may be found on page 165. Published by Joshua Odell Editions Post Office Box 2158, Santa Barbara, CA 93120 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bradbury, Ray, 1920— Zen in the art of writing. 1. Bradbury, Ray, 1920- —Authorship. 2. Creative ability.3. Authorship. 4. Zen Buddhism. I. Title. PS3503. 167478 1989 808'.os 89-25381 ISBN 1-877741-09-4 Printed in the United States of America. Designed by The Sarabande Press TO MY FINEST TEACHER, JENNET JOHNSON, WITH LOVE CONTENTS PREFACE xi THE JOY OF WRITING 3 RUN FAST, STAND STILL, OR, THE THING AT THE TOP OF THE STAIRS, OR, NEW GHOSTS FROM OLD MINDS 13 HOW TO KEEP AND FEED A MUSE 31 DRUNK, AND IN CHARGE OF A BICYCLE 49 INVESTING DIMES: FAHRENHEIT 451 69 JUST THIS SIDE OF BYZANTIUM: DANDELION WINE 79 THE LONG ROAD TO MARS 91 ON THE SHOULDERS OF GIANTS 99 THE SECRET MIND 111 SHOOTING HAIKU IN A BARREL 125 ZEN IN THE ART OF WRITING 139 .