O Michael Barnett This Paper Is Not to Be Quoted Or Used Without the Author's Express Permission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dub Issue 15 August2017

AIRWAVES DUB GREEN FUTURES FESTIVAL RADIO + TuneIn Radio Thurs - 9-late - Cornerstone feat.Baps www.greenfuturesfestivals.org.uk/www.kingstongreenradi o.org.uk DESTINY RADIO 105.1FM www.destinyradio.uk FIRST WEDNESDAY of each month – 8-10pm – RIDDIM SHOW feat. Leo B. Strictly roots. Sat – 10-1am – Cornerstone feat.Baps Sun – 4-6pm – Sir Sambo Sound feat. King Lloyd, DJ Elvis and Jeni Dami Sun – 10-1am – DestaNation feat. Ras Hugo and Jah Sticks. Strictly roots. Wed – 10-midnight – Sir Sambo Sound NATURAL VIBEZ RADIO.COM Daddy Mark sessions Mon – 10-midnight Sun – 9-midday. Strictly roots. LOVERS ROCK RADIO.COM Mon - 10-midnight – Angela Grant aka Empress Vibez. Roots Reggae as well as lo Editorial Dub Dear Reader First comments, especially of gratitude, must go to Danny B of Soundworks and Nick Lokko of DAT Sound. First salute must go to them. When you read inside, you'll see why. May their days overflow with blessings. This will be the first issue available only online. But for those that want hard copies, contact Parchment Printers: £1 a copy! We've done well to have issued fourteen in hard copy, when you think that Fire! (of the Harlem Renaissance), Legitime Defense and Pan African were one issue publications - and Revue du Monde Noir was issued six times. We're lucky to have what they didn't have – the online link. So I salute again the support we have from Sista Mariana at Rastaites and Marco Fregnan of Reggaediscography. Another salute also to Ali Zion, for taking The Dub to Aylesbury (five venues) - and here, there and everywhere she goes. -

Chant Down Babylon: the Rastafarian Movement and Its Theodicy for the Suffering

Verge 5 Blatter 1 Chant Down Babylon: the Rastafarian Movement and Its Theodicy for the Suffering Emily Blatter The Rastafarian movement was born out of the Jamaican ghettos, where the descendents of slaves have continued to suffer from concentrated poverty, high unemployment, violent crime, and scarce opportunities for upward mobility. From its conception, the Rastafarian faith has provided hope to the disenfranchised, strengthening displaced Africans with the promise that Jah Rastafari is watching over them and that they will someday find relief in the promised land of Africa. In The Sacred Canopy , Peter Berger offers a sociological perspective on religion. Berger defines theodicy as an explanation for evil through religious legitimations and a way to maintain society by providing explanations for prevailing social inequalities. Berger explains that there exist both theodicies of happiness and theodicies of suffering. Certainly, the Rastafarian faith has provided a theodicy of suffering, providing followers with religious meaning in social inequality. Yet the Rastafarian faith challenges Berger’s notion of theodicy. Berger argues that theodicy is a form of society maintenance because it allows people to justify the existence of social evils rather than working to end them. The Rastafarian theodicy of suffering is unique in that it defies mainstream society; indeed, sociologist Charles Reavis Price labels the movement antisystemic, meaning that it confronts certain aspects of mainstream society and that it poses an alternative vision for society (9). The Rastas believe that the white man has constructed and legitimated a society that is oppressive to the black man. They call this society Babylon, and Rastas make every attempt to defy Babylon by refusing to live by the oppressors’ rules; hence, they wear their hair in dreads, smoke marijuana, and adhere to Marcus Garvey’s Ethiopianism. -

Rastalogy in Tarrus Riley's “Love Created I”

Rastalogy in Tarrus Riley’s “Love Created I” Darren J. N. Middleton Texas Christian University f art is the engine that powers religion’s vehicle, then reggae music is the 740hp V12 underneath the hood of I the Rastafari. Not all reggae music advances this movement’s message, which may best be seen as an anticolonial theo-psychology of black somebodiness, but much reggae does, and this is because the Honorable Robert Nesta Marley OM, aka Tuff Gong, took the message as well as the medium and left the Rastafari’s track marks throughout the world.1 Scholars have been analyzing such impressions for years, certainly since the melanoma-ravaged Marley transitioned on May 11, 1981 at age 36. Marley was gone too soon.2 And although “such a man cannot be erased from the mind,” as Jamaican Prime Minister Edward Seaga said at Marley’s funeral, less sanguine critics left others thinking that Marley’s demise caused reggae music’s engine to cough, splutter, and then die.3 Commentators were somewhat justified in this initial assessment. In the two decades after Marley’s tragic death, for example, reggae music appeared to abandon its roots, taking on a more synthesized feel, leading to electronic subgenres such as 1 This is the basic thesis of Carolyn Cooper, editor, Global Reggae (Kingston, Jamaica: Canoe Press, 2012). In addition, see Kevin Macdonald’s recent biopic, Marley (Los Angeles, CA: Magonlia Home Entertainment, 2012). DVD. 2 See, for example, Noel Leo Erskine, From Garvey to Marley: Rastafari Theology (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2004); Dean MacNeil, The Bible and Bob Marley: Half the Story Has Never Been Told (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2013); and, Roger Steffens, So Much Things to Say: The Oral History of Bob Marley, with an introduction by Linton Kwesi Johnson (New York and London: W.W. -

The True Story of Rastafari Lucy Mckeon

The True Story of Rastafari Lucy McKeon A mural of Leonard Howell in Tredegar Park, near where the first Rastafari community was formed in the 1930s, Spanish Town, Jamaica, January 4, 2014 In the postcard view of Jamaica, Bob Marley casts a long shadow. Though he’s been dead for thirty-five years, the legendary reggae musician is easily the most recognizable Jamaican in the world—the primary figure in a global brand often associated with protest music, laid-back, “One Love” positivity, and a pot-smoking counterculture. And since Marley was an adherent of Rastafari, the social and spiritual movement that began in this Caribbean island nation in the 1930s, his music—and reggae more generally—have in many ways come to be synonymous with Rastafari in the popular imagination. For Jamaica’s leaders, Rastafari has been an important aspect of the country’s global brand. Struggling with sky-high unemployment, vast inequality, and extreme poverty (crippling debt burdens from IMF agreements haven’t helped the situation), they have relied on Brand Jamaica—the government’s explicit marketing push, beginning in the 1960s—to attract tourist dollars and foreign investment to the island. The government-backed tourist industry has long encouraged visitors to Come to Jamaica and feel all right; and in 2015, the country decriminalized marijuana— creating a further draw for foreigners seeking an authentic Jamaican experience. The Jamaica Property Office (JIPO), part of the government’s larger Jamaican Promotions Agency (JAMPRO), works to protect the country’s name and trademarks from registration by outside entities with no connection to Jamaican goods and 2 services. -

O. Lake the Many Voices of Rastafarian Women

O. Lake The many voices of Rastafarian women : sexual subordination in the midst of liberation Author calls it ironic that although Rasta men emphasize freedom, their relationship to Rasta women is characterized by a posture and a rhetoric of dominance. She analyses the religious thought and institutions that reflect differential access to material and cultural resources among Rastafarians. Based on the theory that male physical power and the cultural institutions created by men set the stage for male domination over women. In: New West Indian Guide/ Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 68 (1994), no: 3/4, Leiden, 235-257 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com10/01/2021 06:46:12PM via free access OBIAGELE LAKE THE MANY VOICES OF RASTAFARIAN WOMEN: SEXUAL SUBORDINATION IN THE MIDST OF LIBERATION Jamaican Rastafarians emerged in response to the exploitation and oppres- sion of people of African descent in the New World. Ironically, although Rasta men have consistently demanded freedom from neo-colonialist forces, their relationship to Rastafarian women is characterized by a pos- ture and a rhetoric of dominance. This discussion of Rastafarian male/ female relations is significant in so far as it contributes to the larger "biology as destiny" discourse (Rosaldo & Lamphere 1974; Reiter 1975; Etienne & Leacock 1980; Moore 1988). While some scholars claim that male dom- ination in indigenous and diaspora African societies results from Ëuropean influence (Steady 1981:7-44; Hansen 1992), others (Ortner 1974; Rubin 1975; Brittan 1989) claim that male physical power and the cultural institu- tions created by men, set the stage for male domination over women in all societies. -

Afro-Jamaican Religio-Cultural Epistemology and the Decolonization of Health

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School March 2020 Mystic Medicine: Afro-Jamaican Religio-Cultural Epistemology and the Decolonization of Health Jake Wumkes University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the African Studies Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the Religion Commons Scholar Commons Citation Wumkes, Jake, "Mystic Medicine: Afro-Jamaican Religio-Cultural Epistemology and the Decolonization of Health" (2020). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/8311 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mystic Medicine: Afro-Jamaican Religio-Cultural Epistemology and the Decolonization of Health by Jake Wumkes A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Latin American, Caribbean, and Latino Studies Department of School of Interdisciplinary Global Studies College of Arts & Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Bernd Reiter, Ph.D. Tori Lockler, Ph.D. Omotayo Jolaosho, Ph.D. Date of Approval: February 27, 2020 Keywords: Healing, Rastafari, Coloniality, Caribbean, Holism, Collectivism Copyright © 2020, Jake Wumkes Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................... -

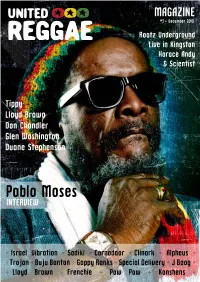

Pablo Moses INTERVIEW

MAGAZINE #3 - December 2010 Rootz Underground Live in Kingston Horace Andy & Scientist Tippy Lloyd Brown Don Chandler Glen Washington Duane Stephenson Pablo Moses INTERVIEW * Israel Vibration * Sadiki * Cornadoor * Clinark * Alpheus * * Trojan * Buju Banton * Gappy Ranks * Special Delivery * J Boog * * Lloyd Brown * Frenchie * Pow Pow * Konshens * United Reggae Mag #3 - December 2010 Want to read United Reggae as a paper magazine? In addition to the latest United Reggae news, views andNow videos you online can... each month you can now enjoy a free pdf version packed with most of United Reggae content from the last month.. SUMMARY 1/ NEWS •Lloyd Brown - Special Delivery - Own Mission Records - Calabash J Boog - Konshens - Trojan - Alpheus - Racer Riddim - Everlasting Riddim London International Ska Festival - Jamaican-roots.com - Buju Banton, Gappy Ranks, Irie Ites, Sadiki, Tiger Records 3 - 9 2/ INTERVIEWS •Interview: Tippy 11 •Interview: Pablo Moses 15 •Interview: Duane Stephenson 19 •Interview: Don Chandler 23 •Interview: Glen Washington 26 3/ REVIEWS •Voodoo Woman by Laurel Aitken 29 •Johnny Osbourne - Reggae Legend 30 •Cornerstone by Lloyd Brown 31 •Clinark - Tribute to Michael Jackson, A Legend and a Warrior •Without Restrictions by Cornadoor 32 •Keith Richards’ sublime Wingless Angels 33 •Reggae Knights by Israel Vibration 35 •Re-Birth by The Tamlins 36 •Jahdan Blakkamoore - Babylon Nightmare 37 4/ ARTICLES •Is reggae dying a slow death? 38 •Reggae Grammy is a Joke 39 •Meet Jah Turban 5/ PHOTOS •Summer Of Rootz 43 •Horace Andy and Scientist in Paris 49 •Red Strip Bold 2010 50 •Half Way Tree Live 52 All the articles in this magazine were previously published online on http://unitedreggae.com.This magazine is free for download at http://unitedreggae.com/magazine/. -

Carlton Barrett

! 2/,!.$ 4$ + 6 02/3%2)%3 f $25-+)4 7 6!,5%$!4 x]Ó -* Ê " /",½-Ê--1 t 4HE7ORLDS$RUM-AGAZINE !UGUST , -Ê Ê," -/ 9 ,""6 - "*Ê/ Ê /-]Ê /Ê/ Ê-"1 -] Ê , Ê "1/Ê/ Ê - "Ê Ê ,1 i>ÌÕÀ} " Ê, 9½-#!2,4/."!22%44 / Ê-// -½,,/9$+.)"" 7 Ê /-½'),3(!2/.% - " ½-Ê0(),,)0h&)3(v&)3(%2 "Ê "1 /½-!$2)!.9/5.' *ÕÃ -ODERN$RUMMERCOM -9Ê 1 , - /Ê 6- 9Ê `ÊÕV ÊÀit Volume 36, Number 8 • Cover photo by Adrian Boot © Fifty-Six Hope Road Music, Ltd CONTENTS 30 CARLTON BARRETT 54 WILLIE STEWART The songs of Bob Marley and the Wailers spoke a passionate mes- He spent decades turning global audiences on to the sage of political and social justice in a world of grinding inequality. magic of Third World’s reggae rhythms. These days his But it took a powerful engine to deliver the message, to help peo- focus is decidedly more grassroots. But his passion is as ple to believe and find hope. That engine was the beat of the infectious as ever. drummer known to his many admirers as “Field Marshal.” 56 STEVE NISBETT 36 JAMAICAN DRUMMING He barely knew what to do with a reggae groove when he THE EVOLUTION OF A STYLE started his climb to the top of the pops with Steel Pulse. He must have been a fast learner, though, because it wouldn’t Jamaican drumming expert and 2012 MD Pro Panelist Gil be long before the man known as Grizzly would become one Sharone schools us on the history and techniques of the of British reggae’s most identifiable figures. -

The Rastafarian Movement in Jamaica Bachelor’S Diploma Thesis

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Bakalářská diplomová práce Michal Šilberský Michal 2010 Michal Šilberský 20 10 10 Hřbet Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Michal Šilberský The Rastafarian Movement in Jamaica Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. Martina Horáková, Ph. D. 2010 - 2 - I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature - 3 - I would like to thank my supervisor Mgr. Martina Horáková, Ph.D. for her helpful advice and the time devoted to my thesis. - 4 - Table of Contents 1. Introduction 6 2. History of Jamaica 8 3. The Rastafarian Movement 13 3.1. Origins 13 3.2. The Beginnings of the Rastafarian Movement 22 3.3. The Rastafarians 25 3.3.1. Dreadlocks 26 3.3.2. I-tal 27 3.3.3. Ganja 28 3.3.4. Dread Talk 29 3.3.5. Ethiopianism 30 3.3.6. Music 32 3.4. The Rastafarian Movement after Pinnacle 35 4. The Influence of the Rastafarian Movement on Jamaica 38 4.1. Tourism 38 4.2. Cinema 41 5. Conclusion 44 6. Bibliography 45 7. English Resumé 48 8. Czech Resumé 49 - 5 - 1. Introduction Jamaica has a rich history of resistance towards the European colonization. What started with black African slave uprisings at the end of the 17th century has persisted till 20th century in a form of the Rastafarian movement. This thesis deals with the Rastafarian movement from its beginnings, to its most violent period, to the inclusion of its members within the society and shows, how this movement was perceived during the different phases of its growth, from derelicts and castaways to cultural bearers. -

Samson and Moses As Moral Exemplars in Rastafari

WARRIORS AND PROPHETS OF LIVITY: SAMSON AND MOSES AS MORAL EXEMPLARS IN RASTAFARI __________________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board __________________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY __________________________________________________________________ by Ariella Y. Werden-Greenfield July, 2016 __________________________________________________________________ Examining Committee Members: Terry Rey, Advisory Chair, Temple University, Department of Religion Rebecca Alpert, Temple University, Department of Religion Jeremy Schipper, Temple University, Department of Religion Adam Joseph Shellhorse, Temple University, Department of Spanish and Portuguese © Copyright 2016 by Ariella Y. Werden-Greenfield All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT Since the early 1970’s, Rastafari has enjoyed public notoriety disproportionate to the movement’s size and humble origins in the slums of Kingston, Jamaica roughly forty years earlier. Yet, though numerous academics study Rastafari, a certain lacuna exists in contemporary scholarship in regards to the movement’s scriptural basis. By interrogating Rastafari’s recovery of the Hebrew Bible from colonial powers and Rastas’ adoption of an Israelite identity, this dissertation illuminates the biblical foundation of Rastafari ethics and symbolic registry. An analysis of the body of scholarship on Rastafari, as well as of the reggae canon, reveals -

The Swell and Crash of Ska's First Wave : a Historical Analysis of Reggae's Predecessors in the Evolution of Jamaican Music

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 2014 The swell and crash of ska's first wave : a historical analysis of reggae's predecessors in the evolution of Jamaican music Erik R. Lobo-Gilbert California State University, Monterey Bay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes Recommended Citation Lobo-Gilbert, Erik R., "The swell and crash of ska's first wave : a historical analysis of reggae's predecessors in the evolution of Jamaican music" (2014). Capstone Projects and Master's Theses. 366. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes/366 This Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. Unless otherwise indicated, this project was conducted as practicum not subject to IRB review but conducted in keeping with applicable regulatory guidance for training purposes. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Erik R. Lobo-Gilbert CSU Monterey Bay MPA Recording Technology Spring 2014 THE SWELL AND CRASH OF SKA’S FIRST WAVE: A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF REGGAE'S PREDECESSORS IN THE EVOLUTION OF JAMAICAN MUSIC INTRODUCTION Ska music has always been a truly extraordinary genre. With a unique musical construct, the genre carries with it a deeply cultural, sociological, and historical livelihood which, unlike any other style, has adapted and changed through three clearly-defined regional and stylistic reigns of prominence. The music its self may have changed throughout the three “waves,” but its meaning, its message, and its themes have transcended its creation and two revivals with an unmatched adaptiveness to thrive in wildly varying regional and sociocultural climates. -

Rastafarians and Orthodoxy

Norman Hugh Redington Rastafarians and Orthodoxy From Evangelion, Newsletter of the Orthodox Society of St Nicholas of Japan (Arcadia, South Africa), Number 27, September 1994: “Orthodoxy and Quasi-Orthodoxy”* Orthodox mission reached one of its lowest points in the fifty years between 1920 and 1970. The Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and its consequences virtually put a stop to any mission outreach by the Orthodox Church. In the same period there was an enormous growth in Christian and semi-Christian new religious groups and movements. In South Africa alone there are nearly 8000 different African independent churches. Wandering “bishops” (episcopi vagantes) travelled the world, starting new sects and denominations as they went. Some of the groups wanted to be Orthodox, and many thought they were Orthodox. In recent years, many of these groups have been “coming home”, seeking in one way or another to be united to canonical Orthodoxy. Many of these groups have connections with one another, either through common origins, or because they have later joined with each other. Some groups are found in South Africa, some in other places. There are often connections between groups in different parts of the world. In this issue of Evangelion we will look at some of these groups. * Evangelion is a newsletter for those interested in Orthodox Christian mission and evangelism. It is published by the Orthodox Society of St Nicholas of Japan, and is sent free of charge to members of the society and to anyone else who asks for it. The Society exists to encourage Orthodox Christians to participate in the global mission of the Church, and to enable non-Orthodox to become better informed about Orthodoxy.