The Adventures of Captain Hatteras

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birth in Nantes of Jules Verne, to Pierre, a Lawyer, and Sophie, of Distant Scottish Descent

A CHRONOLOGY OF J ULES V ERNE William Butcher 1828 8 February: birth in Nantes of Jules Verne, to Pierre, a lawyer, and Sophie, of distant Scottish descent. The parents have links with reactionary milieux and the slave trade. They move to 2 Quai Jean-Bart, with a magnificent view over the Loire. 1829 Birth of brother, Paul, followed by sisters Anna (1837), Mathilde (1839) and Marie (1842). 1834–7 Boarding school. The Vernes spend the summers in bucolic countryside with a buccaneer uncle, where Jules writes his travel dreams. His cousins drown in the Loire. 1837–9 École Saint-Stanislas. Performs well in geography, translation and singing. For half the year, the Vernes stay in Chantenay, overlooking the Loire. Jules’s boat sinks near an island, and he re-enacts Crusoe. Runs away to sea, but is caught by his father. 1840–2 Petit séminaire de Saint-Donitien. The family move to 6 Rue Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Jules writes in various genres, his father predicting a future as a ‘savant’. 1843 Collège royal de Nantes, but missing a year’s studies. 1844–6 In love with his cousin Caroline. Writes plays and short prose pieces. Easily passes baccalauréat. 1847 Studies law in the Latin Quarter. Fruitless passion for Herminie Arnault-Grossetière, dedicating her scores of poems. 1848–9 In the literary salons meets Dumas père and fils, and perhaps Victor Hugo. Law degree. 1850 Comedy ‘Broken Straws’ runs for twelve nights. 1851 Publishes short stories ‘Drama in Mexico’ and ‘Drama in the Air’. Works as private tutor, bank clerk and law clerk. -

Astronomy and Astronomers in Jules Verne's Novels

The Rˆole of Astronomy in Society and Culture Proceedings IAU Symposium No. 260, 2009 c 2009 International Astronomical Union D. Valls-Gabaud & A. Boksenberg, eds. DOI: 00.0000/X000000000000000X Astronomy and astronomers in Jules Verne’s novels Jacques Crovisier Observatoire de Paris, 5 place Jules Janssen, 92195 Meudon, France email: [email protected] Abstract. Almost all the Voyages Extraordinaires written by Jules Verne refer to astronomy. In some of them, astronomy is even the leading theme. However, Jules Verne was basically not learned in science. His knowledge of astronomy came from contemporaneous popular publications and discussions with specialists among his friends or his family. In this article, I examine, from the text and illustrations of his novels, how astronomy was perceived and conveyed by Jules Verne, with errors and limitations on the one hand, with great respect and enthusiasm on the other hand. This informs us on how astronomy was understood by an “honnˆete homme” in the late 19th century. Keywords. Verne J., literature, 19th century 1. Introduction Jules Verne (1828–1905) wrote more than 60 novels which constitute the Voyages Extraordinaires series†. Most of them were scientific novels, announcing modern science fiction. However, following the strong suggestions of his editor Pierre-Jules Hetzel, Jules Verne promoted science in his novels, so that they could be sold as educational material to the youth (Fig. 1). Jules Verne had no scientific education. He relied on popular publications and discussions with specialists chosen among friends and relatives. This article briefly presents several examples of how astronomy appears in the text and illustrations of the Voyages Extraordinaires. -

80 Days Adaptations

TABLE OF CONTENTS About ATC . 1 Introduction to the Play . 2 THIS IS Synopsis . 2 Meet the Characters . 3 DEFINITELY Meet the Creators . 5 NOT THE An Interview with Mark Brown . 6 QUIET LIFE From Page to Stage: 80 Days Adaptations . 7 I WAS 80 Days: The Journey . 9 Cultural Context: 19th Century Britain . 15 LOOKING FOR. – Passepartout, References and Glossary . 17 Around the World in 80 Days Discussion Questions and Activities . 23 Around the World in 80 Days Play Guide written and compiled by Katherine Monberg, ATC Literary Associate; April Jackson, Tucson Education Manager; and Amber Justmann, Literary Intern . Discussion questions and activities provided by April Jackson, Tucson Education Manager; Amber Tibbitts, Phoenix Education Manager; and Bryanna Patrick, Education Associate . SUPPORT FOR ATC’S EDUCATION AND COMMUNITY PROGRAMMING HAS BEEN PROVIDED BY: APS JPMorgan Chase The Lovell Foundation Arizona Commission on the Arts John and Helen Murphy Foundation The Marshall Foundation Bank of America Foundation National Endowment for the Arts The Maurice and Meta Gross Foundation Blue Cross Blue Shield Arizona Phoenix Office of Arts and Culture The Max and Victoria Dreyfus Foundation City of Glendale PICOR Charitable Foundation The Stocker Foundation Community Foundation for Southern Arizona Rosemont Copper The William L . and Ruth T . Pendleton Cox Charities Stonewall Foundation Memorial Fund Downtown Tucson Partnership Target Tucson Medical Center Enterprise Holdings Foundation The Boeing Company Tucson Pima Arts Council Ford Motor Company Fund The Donald Pitt Family Foundation Wells Fargo Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold Foundation The Johnson Family Foundation, Inc . ABOUT ATC Arizona Theatre Company is a professional, not-for-profit theatre company . -

Download The

DAVID LINDSAY'S A VOYAGE TO ARCTURUS ALLEGORICAL DREAM FANTASY AS A LITERARY MODE by JACK S CHOFIELD B.A., University of Birmingham, 1969 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September, 19 72 tn presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada Date Abstract David Lindsay's A Voyage to Arcturus must be read as an allegorical dream fantasy for its merit to be correctly discerned. Lindsay's central themes are introduced in a study of the man and his work. (Ch. 1). These themes are found to be common in allegorical dream fantasy, the phenomen- ological background of which is established (Ch. 2). A distinction can then be drawn between fantasy and romance, so as to define allegorical dream fantasy as a literary mode (Ch. 3). After the biographical, theoretical and literary backgrounds of A Voyage have been established in the first three chapters, the second three chapters explicate the structure of the book as an allegorical dream fantasy. -

The Sphinx of the Ice Realm Ably Well-Known Item, It Regularly Turns up in Discussions of Poe’S the Narrative of Arthur

Translating Verne runs the old Italian adage: translators are traitors. And it’s raduttore, traditore possible that no big-name author has suffered more betrayals than Frenchman TJules Verne in his nineteenth-century English translations. Fans and academics have been pointing out this problem for decades. It was in the turbulent 1960s that NYU scholar Walter James Miller made a startling discov- ery: Captain Nemo’s famed submarine, the , was manufactured from a revolutionary Nautilus type of sheet iron that was lighter than water and could float. Well, not really. Checking Verne’s French, Miller verified that the translator had sim- ply made an idiotic mistake. And then other readers started finding other kinks: the first English version of (1864) recomposed every third paragraph Journey to the Center of the Earth and gave the characters silly new monikers—Verne’s Professor Lidenbrock became Profes- sor Hardwigg. As for more literal translations, often they were preposterously abridged: in (1869) Verne includes an amusing chapter on using algebra to calculate Circling the Moon flight times—the original translator kept the chapter but left out the formulas. And then there were issues of political correctness: in (1875) Verne condemns The Mysterious Island the British Raj—his UK translator simply revamped him so that he voices support instead. In short, the Victorian translations of many Verne novels not only abound in asinine errors, they condense him, censor him, rewrite him, drop whole passages, fabricate new ones, concoct different titles, rearrange chapters, redo characterizations, chop his descriptions, dump his science, axe his jokes, and generally delete things that are politically iffy or call for homework. -

Redalyc.SCIENCE in VERNE and POE the PYM CASE

Mètode Science Studies Journal ISSN: 2174-3487 [email protected] Universitat de València España Bonet Safont, Juan Marcos SCIENCE IN VERNE AND POE THE PYM CASE Mètode Science Studies Journal, núm. 6, 2016, pp. 6-12 Universitat de València Valencia, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=511754471004 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Mètode 6 MÈTODE DOCUMENT MÈTODE Science Studies Journal, 6 (2016): 6–12. University of Valencia. DOI: 10.7203/metode.85.3315 ISSN: 2174-3487. Article received: 20/02/2014, accepted: 09/07/2014. SCIENCE IN VERNE AND POE THE PYM CASE JUAN MARCOS BONET SAFONT In 1897, Jules Verne’s novel An antarctic mystery was published both in periodical form and as a complete book. It is a continuation of Edgar Allan Poe’s story The narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (1838). In this article, we will use the plots of both novels to show the different images of science and technology presented by the two authors. We address both Verne’s and Poe’s approach to science, as conveyed through their fictional stories. We also discuss how Verne’s scientific descriptions are much more extensive than Poe’s, a testament to Verne’s rational and learned character, as opposed to Poe’s more fantastic and imaginative approach to science. Keywords: Poe, Verne, science and literature, Pym, South Pole. -

Volume 1 (2008-2009)

V E R N I A N A Jules Verne Studies – Etudes Jules Verne Vol. 1 2008-2009 Initial capital “V” copyright ©1972 Richard Aeschlimann, Yverdon- les-Bains (Switzerland). Reproduced with his permission. La lettrine “V” de couverture est copyright ©1972 Richard Aeschlimann, Yverdon-les-Bains (Suisse). Elle est reproduite ici avec son autorisation. V E R N I A N A Jules Verne Studies – Etudes Jules Verne Vol. 1 2008-2009 Editorial Board – Comité de rédaction William Butcher Daniel Compère Volker Dehs Arthur B. Evans Terry Harpold Jean-Michel Margot Walter James Miller Garmt de Vries-Uiterweerd ISSN : 1565-8872 V E R N I A N A Jules Verne Studies – Etudes Jules Verne Vol. 1 - 2008-2009 Editorial The Editors ― “Dr. Zvi Har’El (December 14, 1949-February 2, 2008) and International Jules Verne Studies - A Tribute” i Le Comité de redaction ― “Dr. Zvi Har’El (14 décembre 1949-2 février 2008) et les Etudes internationales Jules Verne - Un Hommage” iii Daniel Compère ― “Editorial (Français)” v Daniel Compère ― “Editorial (English)” vii Articles Walter James Miller ― “As Verne Smiles” 1 Arthur B. Evans ― “Jules Verne in English: A Bibliography of Modern Editions and Scholarly Studies” 9 Brian Taves ― “Expedition Into a Novel” 23 Terry Harpold ― “Verne’s Errant Readers: Nemo, Clawbonny, Michel Dufrénoy” 31 Ian Thompson & Philippe Valetoux – “Jules Verne’s visits to Gibraltar in 1878 and 1884” 43 Brian Taves - “Opening the Sources of The Kip Brothers: A Generic Interpretation” 51 Reviews Dave Bonte ― “Le Voyage à travers l’impossible (1882) en néerlandais” 65 Upcoming Conferences and Symposia Conférences et Symposia à venir The 2009 Eaton Science Fiction Conference - Extraordinary Voyages: Jules Verne 67 and Beyond - April 30-May 3, 2009 - University of California, Riverside Index of Authors and Editorial Board Members - Index des auteurs et membres 69 du Comité de rédaction ISSN : 1565-8872 Dr. -

Jules Verne. the Sphinx of the Ice Realm

DePauw University Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University Modern Languages Faculty Publications Modern Languages 2013 Another Excellent Verne Translation Arthur B. Evans DePauw University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.depauw.edu/mlang_facpubs Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons Recommended Citation Evans, Arthur B. "Another Excellent Verne Translation." [Review of Jules Verne's The Sphinx of the Ice Realm. Trans. and ed. Frederick Paul Walter. Albany, NY: Excelsior, 2012]. Science Fiction Studies 40.3 (2013): 572-575 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Modern Languages at Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern Languages Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 572 SCIENCE FICTION STUDIES, VOLUME 40 (2013) BOOKS IN REVIEW Another Excellent Verne Translation. Jules Verne. The Sphinx of the Ice Realm: The First Complete English Translation, with the Full Text of The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym by Edgar Allan Poe. Trans. and ed. Frederick Paul Walter. Albany: State U of New York P/Excelsior, 2012. xix + 413 pp. $24.95 pbk. The past couple of decades have witnessed a resurgence of interest in Jules Verne and the appearance of a host of new English translations of his legendary Voyages Extraordinaires. For example, Oxford University Press’s “World’s Classics” series has published several fine translations by William Butcher, including Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1864) in 1992, Around the World in 80 Days (1873) in 1995, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas (1870) in 1998, and The Adventures of Captain Hatteras (1866) in 2005. -

Jules Verne Studies – Etudes Jules Verne Vol

V E R N I A N A Jules Verne Studies – Etudes Jules Verne Vol. 2 2009–2010 Initial capital “V” copyright ©1972 Richard Aeschlimann, Yverdon- les-Bains (Switzerland). Reproduced with his permission. La lettrine “V” de couverture est copyright ©1972 Richard Aeschlimann, Yverdon-les-Bains (Suisse). Elle est reproduite ici avec son autorisation. V E R N I A N A Jules Verne Studies – Etudes Jules Verne Vol. 2 2009–2010 ISSN : 1565-8872 Editorial Board – Comité de rédaction William Butcher ([email protected] and http://www.ibiblio.org/julesverne) has taught at the École nationale d’administration, researched at the École normale supérieure and Oxford, and is now a Hong Kong property developer. His publications since 1980, notably for Macmillan, St Martin’s and Gallimard, include Verne’s Journey to the Centre of the Self, Jules Verne: The Definitive Biography and Salon de 1857. In addition to a series of Verne novels for OUP, he has recently published a critical edition of Le Tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours. Daniel Compère ([email protected]) est professeur de littérature française à l’Université de Paris III-Sorbonne nouvelle. Créateur du Centre Jules Verne d’Amiens en 1972, il a publié de nombreux ouvrages et articles sur Jules Verne (dont Les Voyages extraordinaires de Jules Verne. Pocket, 2005). Président de l’Association des Amis du Roman populaire et responsable de la revue Le Rocambole, il a également consacré des publications à la littérature populaire dont deux livres sur Alexandre Dumas (dont D’Artagnan & Cie. Les Belles Lettres - Encrage, 2002). -

Following in the Footsteps of Sir Walter Scott Seventeen Days In

Following in the Footsteps of Sir Walter Scott: Eighteen Days in Scotland Lingwei Meng Göttingen November 2016 For Prof. Dr. Barbara Schaff Dr. Kirsten Sandrock Contents Introduction......................................................................................................................................... 1 First Day: Callaner.............................................................................................................................. 2 Second Day: Rob Roy’s Grave and Ledard Waterfall........................................................................ 3 Third Day: Loch Katrine - Inversnaid - Glasgow Cathedral.............................................................. 6 Fourth Day: Stirling Castle............................................................................................................... 10 Fifth Day: Impression on Edinburgh.................................................................................................13 Sixth Day: 25 George Square............................................................................................................15 Seventh Day: Old Site of Tolbooth and St Giles’ Cathedral.............................................................17 Eighth day: A City Tour.....................................................................................................................20 Ninth Day: Old Site of the Mercat Cross and Lady Stair’s Close ................................................22 Tenth Day: St. Andrews................................................................................................................... -

EXHIBITION BOOKLET Voyages Extraordinaires De Femmes Pas Si Ordinaires the WOMEN in VERNE’S LIFE

HÉROÏNES DE LA MODERNITÉ EXHIBITION BOOKLET Voyages extraordinaires de femmes pas si ordinaires THE WOMEN IN VERNE’S LIFE HEROINES OF “You are becoming e é regulars in the salons of g â , s le the Prefecture. I am certain Ju MODERNITY e d ère that this amuses Papa as e, m Women in the works Sophie Vern of Jules Verne much as his daughters, and that Mother would almost Jules Verne is alleged to have had several be prepared to dance there romances in his youth, but he dedicated Jules Verne claimed in 1890 to “have lack the emotional dimension which some thirty poems to the beauty Rose no talent for female characters” yet he humanises the mechanical element if someone were needed to Herminie Arnault-Grossetière. He was created a surprising and diverse gallery and spirit of geographical and scientific not considered to be a good catch and of feminine portraits. conquest of male-centric journeys. make up a quadrille.” was sidelined using the stratagems at Letter from Jules Verne to his mother, which middle-class families excelled. Romantic young women in love, Women are invited to take pride of 21 June 1855. This thwarted love affair cause him patriotic heroines, resourceful place at the Musée Jules Verne for this to leave Nantes. Jules was resentful adventuresses, dominant wives, exhibition. The women who played of these intrigues and exploited them devoted mothers, cunning and ruthless a major role in the writer’s life – his Jules Verne was born on 8 February 1828 in his boulevard theatre plays, later spies, fantasy ghost-women – his mother Sophie, his sisters, and his wife in Nantes. -

Lewintro.Pdf

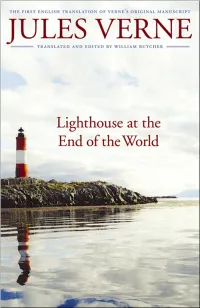

7>HDC;GDCI>:GHD;>B6<>C6I>DC JULES VERNE Lighthouse at the End of theWorld Le Phare du bout du monde The First English Translation of Verne’s Original Manuscript Translated and edited by William Butcher JC>K:GH>IND;C:7G6H@6EG:HH•A>C8DAC Publication of this book was made possible by a grant from The Florence Gould Foundation. Le Phare du bout du monde © Les Éditions internationales Alain Stanké, 1999. © Editions de l’Archipel. Translation and critical apparatus © 2007 by William Butcher. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Verne, Jules, 1828–1905. [Le phare du bout du monde. English] Lighthouse at the end of the world = Le phare du bout du monde : the first English translation of Verne’s original manuscript / Jules Verne ; translated and edited by William Butcher. p. cm. — (Bison frontiers of imagination) Includes bibliographical references. isbn-13: 978-0-8032-4676-8 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn-13: 978-0-8032-6007-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) I. Butcher, William, 1951– II. Title. III. Title: Le phare du bout du monde. pq2469.p4e5 2007 843'.8—dc22 2007001717 Set in Adobe Garamond by Kim Essman. Designed by R. W. Boeche. contents Introduction vii A Chronology of Jules Verne xxxiii Map of Staten Island xxxix 1.Inauguration 1 2. Staten Island 10 3. The Three Keepers 19 4.Kongre's Gang 30 5. The Schooner Maule 41 6. At Elgor Bay 50 7.The Cavern 61 8. Repairing the Maule 70 9.Vasquez 79 10.After the Wreck 89 11.The Wreckers 99 12.