Baldock Walk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BALDOCK, BYGRAVE and CLOTHALL NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN Design Guidelines

BALDOCK, BYGRAVE AND CLOTHALL NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN Design Guidelines March 2019 Quality information Project role Name Position Action summary Signature Date Qualifying body Michael Bingham Baldock , Bygrave and Clothall Review 17.12.2018 Planning Group Director / QA Ben Castell Director Finalisation 9.01.2019 Researcher Niltay Satchell Principal Urban Designer Research, site 9.01.2019 visit, drawings Blerta Dino Urban Designer Project Coordinator Mary Kucharska Project Coordinator Review 12.01.2019 This document has been prepared by AECOM Limited for the sole use of our client (the “Client”) and in accordance with generally accepted consultancy principles, the budget for fees and the terms of reference agreed between AECOM Limited and the Client. Any information provided by third parties and referred to herein has not been checked or verified by AECOM Limited, unless otherwise expressly stated in the document. No third party may rely upon this document without the prior and express written agreement of AECOM Limited. Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................................6 1.1. Background ..........................................................................................................................................................................................................6 1.2. Purpose of this document ............................................................................................................................................................................6 -

Baldock Radio Station Royston Road Baldock Herts SG7 6SH Mobile

ML2-005-04 Baldock Radio Station Royston Road Baldock Herts SG7 6SH Mobile Phone Base-Station Audit Audit Site: St Edmunds Catholic School Nelson Road Twickenham Middlesex TW2 7BB Work Perfomed by Distribution List James Loughlin 3G measurements Lloyd Tailby 1 Field Manager & Report Mrs R Murphy 1 Mike Reynolds 3G measurements Field Officer JP 1 JP 2G measurements Technical Manager 1 T.I. Officer & 2G Report Case/Year file 2 1 ML2-005-04 The Office of Communications (Ofcom) took over the functions of the Radiocommunications Agency, the Independent Television Commission, and the Radio Authority (as well as the Office of Telecommunications and the Broadcasting Standards Commission) on 29th December 2003. Ofcom is located at Riverside House, 2a Southwalk Bridge Road, London SE1 9HA. Tel: 020 7981 3000. Website: www.ofcom.org.uk Baldock Radio Station forms part of the Operations Group of Ofcom. The station address remains at Royston Road, Baldock, Hertfordshire SG7 6SH. Tel: 01462 428500, Fax: 01462 428510 2 ML2-005-04 Report Summary As the radio spectrum is continually changing, these measurements can only provide information on the radio frequency (RF) conditions for the specific locations at the time of the survey. The Office of Communications (Ofcom), originally the Radiocommunications Agency performed this survey of the RF emission environment in the vicinity of the site of St Edmunds Catholic School on 4th February 2004. Both second generation (2G) and third generation (3G) base station emissions were measured separately and the signal levels combined to calculate the Total Band Exposure as detailed below. The table, sorted in descending order of signal level, summarises the total results obtained at each measurement location. -

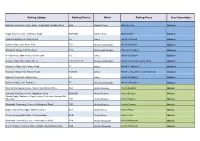

Polling Station List

Polling Station Polling District Ward Polling Place Area Committee Baldock Community Centre, Large / Small Halls, Simpson Drive AAA Baldock Town Baldock Town Baldock Tapps Garden Centre, Wallington Road ABA,ABB Baldock East Baldock East Baldock Ashwell Parish Room, Swan Street FA Arbury Parish of Ashwell Baldock Sandon Village Hall, Payne End FAA Weston and Sandon Parish of Sandon Baldock Wallington Village Hall, The Street FCC Weston and Sandon Paish of Wallington Baldock The Old Forge, Manor Farm, Church Lane FD Arbury Parish of Bygrave Baldock Weston Village Hall, Maiden Street FDD, FDD1, FE Weston and Sandon Parishes of Weston and Clothall Baldock Hinxworth Village Hall, Francis Road FI Arbury Parish of Hinxworth Baldock Newnham Village Hall, Ashwell Road FS1,FS2 Arbury Parishes of Caldecote and Newnham Baldock Radwell Village Hall, Radwell Lane FX Arbury Parish of Radwell Baldock Rushden Village Hall, Rushden FZ Weston and Sandon Parish of Rushden Baldock Westmill Community Centre, Rear of John Barker Place BAA Hitchin Oughton Hitchin Oughton Hitchin Catholic Parish Church Hall, Nightingale Road BBA,BBD Hitchin Bearton Hitchin Bearton Hitchin Hitchin Rugby Clubhouse, King Georges Recreation Ground, Old Hale Way BBB Hitchin Bearton Hitchin Bearton Hitchin Walsworth Community Centre, 88 Woolgrove Road BBC Hitchin Bearton Hitchin Bearton Hitchin Baptist Church Hall, Upper Tilehouse Street BCA Hitchin Priory Hitchin Priory Hitchin St Johns Community Centre, St Johns Road BCB Hitchin Priory Hitchin Priory Hitchin Walsworth Community Centre, 88 Woolgrove Road BDA Hitchin Walsworth Hitchin Walsworth Hitchin New Testament Church of God, Hampden Road/Willian Road BDB Hitchin Walsworth Hitchin Walsworth Hitchin Polling Station Polling District Ward Polling Place Area Committee St Michaels Community Centre, St Michaels Road BDC,BDD Hitchin Walsworth Hitchin Walsworth Hitchin Benslow Music Trust- Fieldfares, Benslow Lane BEA Hitchin Highbury Hitchin Highbury Hitchin Whitehill J.M. -

Club Together Their Garden City Properties

27 31 13 47 17 57 23 Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of all information included in the guide. Please contact any groups in advance to ensure 2 information is still accurate. 3 HERITAGE ADVISORY CENTRE DISCOVER Letchwor th THE ARTS FREE occasional dance meeting spaces for community clubs music Chat to the team about making changes and groups during to your home. offi ce hours fi lm Open Monday to Friday from 10am to 3pm. visual arts 43 Station Road Letchworth Garden City, SG6 3BQ theatre 01462 476017 [email protected] 4 5 DISCOVER THE ARTS DISCOVER THE ARTS BALDOCK MIDNIGHT BRITTON SCHOOL OF GARDEN CITY SAMBA MORRIS PERFORMING ARTS Rehearsing and practising samba Practising and performing morris Dance and musical theatre training. dancing. dancing for ages 14 and over. Every Tuesday to Saturday during Every Tuesday evening. Every Tuesday evening from term-time, sessions at various St Francis’ College, Broadway, January to July and September times. SG6 3PJ to December. Wilbury Hall, Bedford Road, gardencitysamba.com The Scout HQ, Park Drive, SG6 4DU, Icknield Centre, 07527 561755 or Baldock, SG7 6EN SG6 1EF or Lordship Farm School, 07786 638712 baldockmidnightmorris.org.uk Fouracres, SG6 3UF Baldock & Letchworth Blues, 01462 339438 brittonschool.co.uk Folk and Roots Club GARDEN CITY SINGERS info@baldock 07973 308741 midnightmorris.org.uk [email protected] Singing a wide variety of songs in BALDOCK & three and four part harmonies. LETCHWORTH BLUES, Every Wednesday evening, from FOLK AND ROOTS CLUB BEAT REPUBLIC CITY CHORUS January to July and September ACADEMY OF DANCE to December. -

Exploring the Three Cs in Sub-Roman Baldock Author: Keith J

Paper Information: Title: Collapse, Change or Continuity? Exploring the three Cs in sub-Roman Baldock Author: Keith J. Fitzpatrick-Matthews Pages: 132–148 DOI: http://doi.org/10.16995/TRAC2009_132_148 Publication Date: 25 March 2010 Volume Information: Moore, A., Taylor, G., Harris, E., Girdwood, P., and Shipley, L. (eds.) (2010) TRAC 2009: Proceedings of the Nineteenth Annual Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference, Michigan and Southampton 2009. Oxford: Oxbow Books. Copyright and Hardcopy Editions: The following paper was originally published in print format by Oxbow Books for TRAC. Hard copy editions of this volume may still be available, and can be purchased direct from Oxbow at http://www.oxbowbooks.com. TRAC has now made this paper available as Open Access through an agreement with the publisher. Copyright remains with TRAC and the individual author(s), and all use or quotation of this paper and/or its contents must be acknowledged. This paper was released in digital Open Access format in March 2015. Collapse, Change or Continuity? Exploring the three Cs in sub-Roman Baldock Keith J. Fitzpatrick-Matthews Introduction The ‘small towns’ of Roman Britain are the under-theorised ‘Cinderellas’ of the province’s archaeology yet, at the same time, they should be regarded as the great success story of Roman rule. They were the dominant class of urban settlement, with a huge variety of forms, presumably reflecting different social, economic and political roles. Yet studies of the fifth- century collapse of urban civilisation in Britain focus almost exclusively on the major cities and ignore the ‘small towns’. However, because of their diversity, they have the potential to offer unique insights into the processes that operated from the early fifth century on, to transform Roman Britain into the early medieval successor states. -

Hertfordshire. Mil 311 Machinists

TRADES DIREC'rORY.] HERTFORDSHIRE. MIL 311 MACHINISTS. Richardson Charles William, AmweIl Burgin Hy. Flaunden, Chesham S.O Argent James, Victoria st. St. Albans End! Ware ,Bush John, ~uckeridge, Ware Barham Charles L. West alley, Hitchin SedgWIck Mrs. Mary Ann & Co. The ChalIen EdWIn,StansteadAbbots, Ware Dearman WilIiam, Walkern, Stevenage Brewery, Watford . & South wha;rf, ClaphamF.Flamstead end,WalthamCrss Everard Josph. High rd. Waltham Cross Praed street, Paddmgton W.; Stat~on Cox George, Church street, Baldock Hamilton John Buntingford R SO road, West Croydon; SurhIton hIlI, CoxshaIl John, Park la. Waltham Cl'06S Hodgson Nath~n, Stevenage .. Surbiton &Brunswick pI. nth.Brighton FordD.Heronsgate,~ckmanswth.R.S.() Horton WiIliam, 62 High st. Watford Sell R:obert Henry, New road, Ware Ford p.H~r?nsga~,Rlckmanswth.R.S.() Howard George WaIters Britannia ter- Sherrdl' Arthur Jas. North rd. Hatfield Fuller WIlliam, CIllocks farm, Hertford. race Royston' Simpson & Co. High street, Baldock road, Hoddesdon Ivory Henry, Stevenage Taylor H. A. & D. D~ne street, Bishop's George Mrs. Elizabeth, Park street, St. Moore George E. 203 High st. Watford Stortford & Sawbndgeworth R:S.O, Stephens, St. Alb~ns Oliver Archibald Thomas Wandon end Taylor John & Son, Wharf, BIShop s Haden Thomas, Codtcote, Welwyn King's Walden Hitchi~ , Stortford Hale Mrs. Elizabeth, London rd. HertS Park William A~hwell Baldock Taylor Henry AIgernon & Douglas, Harris John, Appleby street, Cheshnut, Smith In. Wheathampstead, St. Albans High street, 'Yare Waltham Cross . Starkey Alfred John, Mill gn. Hatfield ~ard Henry, HIgh street, Ware Mansell Edward, Hadha~road, Bishop's Tregaskiss A.Watton-at-Stone, Hertford" ard Henry, The Wharf. -

Baldock Conservation Area Character Statement Draws on All These Factors to Create a Document That Records Comprehensively What Is ‘Special’ About the Area

NORTH HERTFORDSHIRE DISTRICT COUNCIL CHARACTER STATEMENT FOR BALDOCK CONSERVATION AREA (17th June 2003) 2 CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction 5 2.0 Location and Landscape Setting 7 3.0 Origins and Development 7 4.0 The Architectural and Historic Character of the 11 Buildings 5.0 Prevalent and Traditional Materials 13 6.0 The Contribution made by Green Spaces and Trees 15 7.0 Townscape Analysis 15 7.1 Introduction 15 7.2 The High Street 15 7.3 Whitehorse Street 20 7.4 Hitchin Street 24 7.5 Church Street 26 7.6 Park Street 29 8.0 Negative Features 31 9.0 Neutral or Negative Areas for Improvement 32 10.0 Summary of Special Characteristics 34 Glossary of Terms 37 Bibliography 39 3 4 1.0 INTRODUCTION What are Conservation Areas? 1.1 Conservation areas are very special places. Each one is of ‘special’ architectural or historic importance, with a character or appearance to be preserved or enhanced. Conservation areas are an important part of our heritage and each one is unique and irreplaceable. Their special qualities appeal to visitors and are attractive places to live and work. They provide a strong sense of place and are part of the familiar and local cherished scene. 1.2 Conservation areas are based around groups of buildings, and the spaces created between and around them. It is the quality and interest of areas, rather than that of individual buildings that are the prime consideration in identifying conservation areas. Each area is different and has a distinct character and appearance. Conservation Area Legislation, Government Guidance and Development Plans Conservation Area Legislation 1.3 Conservation areas are defined in The Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 as ‘areas of special architectural or historic interest, the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance’. -

HERTFORDSHIRE. WA.'T 959 • Holland George, Victoria Rd.New Barnet Tprudames Alfred, Hio"H Street, Great Tsimpson Wllliam Church Street Rick

'fRADE:S DIRECTORY.] HERTFORDSHIRE. WA.'t 959 • Holland George, Victoria rd.New Barnet tPrudames Alfred, HiO"h street, Great tSimpson Wllliam Church street Rick.. Howard Bros. High st. Gt. Berkhamsted Berkhamsted & West~rn road, Tring mansworth KS.'O ' HUQ'gins WaIter, Amwell end, Ware tRevill WilIiam Carus Breedon, The tSims In.Chas.106&108High st.Watford Judd Samuel, St. Peter's st. St. Albans Limes, Whitwell, Welwyn, Herts tSimson Edward Augustus & Co. Market Lancaster Benj.45 St.Albans rd.Watford Smith M.High st.Rickmansworth R.S.O place, Hertford Lancaster Chas. Weymouth st. Watford tTraylen Jabez, Braughing, Ware Steptoe Jas. 67 Highst.Hemel Hempstd LeeHenryChas.69Gladstone rd.Watford tWebbJ.Northgate end,Bishop'sStortfrd Street Robert, High street, Hitchin Levasseur W. Marlowes,Hemel Hempstd *Wilson Wm. Highst. Gt. Berkhamsted Thomas Wm. Hy. 162 High st. Barnet 1.0win WilliamHenry,I Clydesdale villas, WingfieldJ.Sarratt,Rickmanswth.R. S.0 Valentine DaYid, Bancroft, Hitchin Turnoc's h1.Cheshunt, Waltham Cross WARDROBE DEALERS Vimpany Harry Daniel, Church street, ~Iiller Arth.Alfd.High rd.WalthamCross . :. Rickmansworth RS.O Neale Samuel & Sons Fore street & 22 Cook Mrs. Ehza, Bucklersbury, Hltrhm Wadsworth John Turner's hill Ches- & 24 Maidenhead st;eet, Hertford R.ansomJobnJaI?es,I87High st.Watford hunt, WaItham'Cross ' Nicklin Wm.D.EastBarnet rd.NewBarnt Slms Mrs. Carolme, I Oscroft road, Box- Webb George James, Ashwell, Baldock Paine Arthur Kirby, High street, Rick- moor, Hemel HeI?pstead Wells John, 15 High street, St. Albans mansworthR.S.O Smyth John, 268 HIgh street, Watford Wells Waiter James,I94 High st. Barnet Payne William Edwin, High st. -

The Cemeteries of Roman Baldock

The Cemeteries of Roman Baldock KEITH J. FITZPATRICK-MATTHEWS North Hertfordshire Museum [email protected] The ancient town of Baldock occupies a shallow bowl in the hills that run west-southwest to east-northeast through North Hertfordshire, a north- eastern extension of the Chilterns (Figure 1). It lies close to the source of the River Ivel, which flows northwards to join the Bedfordshire Ouse, but is not situated on a river. It is also at a road junction, with pre-Roman tracks from Braughing, Verulamium, and Sandy converging with the line of the Icknield Way to the southeast of the springs. It seems to have functioned as a local market centre, with evidence for small-scale craft production, although osteological evidence suggests that a proportion of the townspeople were agricultural labourers. Even so, there is evidence from all periods of a degree of personal wealth and literacy that places at least some of the inhabitants in the upper strata of Romano-British society. This view of the town contrasts with Stead’s (1975, 128) dismissive comment that the town resembled an overgrown Little Woodbury Iron Age farm. Instead, the evidence now points to its success as a cult centre of at least sub-regional importance. Lead sealings that apparently name the settlement and its council (C·VIC—either Curia Vic… or C Vicanorum) demonstrate the presence of a curial class employing the trappings at least Figure 1. Baldock location Fragments Volume 5 (2016) 34 FITZPATRICK-MATTHEWS: The Cemeteries of Roman Baldock of self-government, while the variety of the population’s burials (which include at least two suspected sub-Saharan Africans) and the extreme longevity of the settlement into the fifth century and beyond show it to have been economically successful and socially diverse. -

Goodes Court, Baldock Road, Royston, Hertfordshire SG8 5FP

Goodes Court, Baldock Road, Royston, Hertfordshire SG8 5FP £900 PCM EPC - TBC marshallsproperties.co.uk Goodes Court, Baldock Road , Royston, Hertfordshire SG8 5FP A brand new two bedroom second floor apartment with balcony overlooking Royston Heath. * Two Bedrooms * Second Floor * New Build * Two Allocated Parking Spaces * Ensuite To Master Bedroom * Electric Heating * * uPVC Double Glazing * Open Plan Kitchen/Lounge/Diner * Unfurnished * Available Now* Deposit £1,350 * Tenants Administration Fees will apply * Energy Rating TBC Entrance door to: Television point. uPVC double glazed French BEDROOM TWO: doors opening to Balcony overlooking Royston 10' 1" x 7' 1" (3.08 x 2.15m) uPVC double glazed Heath. RECEPTION HALL: window to rear. Wall mounted electric heater. Telephone entry sys tem. Cupboard housing BEDROOM ONE: Television point. Telephone point. ‘Megaflo’ Hot water tank and linen shelf. Storage cupboard. Telephone point. 12' 11" x 8' 8" (3.93m x 2.65m) uPVC double BATHROOM: glazed window to rear. Wall mounted electric Panel enclosed bath. Pedestal wash hand OPEN PLAN KITCHEN/DINER/LOUNGE: heater. Television point. Telephone point. Built in wardrobe. Door to ensuite. basin. Low level W.C. Tiled splashbacks. 21' x 12' 2" reducing to 8' 10" (6.41m x 3.72m Extractor fan. Heated towel rail radiator. reducing to 2.68). Range of fitted wall and base ENSUITE: Shaver point. Vinyl Flooring. units with work surfaces ove r. One and a half bowl drainer sink unit. Integrated Hotpoint Corner walk in shower cubicl e. Pedestal wash electric oven and hob with extractor hood over. hand basin. Low level W.C. Tiled splashbacks. -

Inns and Innkeeping in North Hertfordshire: 1660

INNS AND INNKEEPING IN NORTH HERTFORDSHIRE: 1660 - 1815 Annika McQueen Wolfson College Faculty of Architecture and History of Art Department of Building History University of Cambridge The full version of this dissertation was submitted for the degree of Master of Studies in Building History in May 2019. A copy is held by the Architecture and History of Art Library, University of Cambridge. This is a redacted version in adherence to copyright regulations. © Annika McQueen, 2019 1 Editorial Conventions In direct quotations from contemporary sources, the original spelling and capitalisation has been retained. Modern punctuation has been inserted in the case of lists. Old Style dating in contemporary sources has been addressed by the use of a slash date separator where the New Style dating equivalent is uncertain e.g. 1684/5. Currency is in pounds (£), shillings (s) and pence (d): there were 12 old pence to the shilling, 20 shillings or 240 old pence to the pound. Unless otherwise attributed, all drawings and photographs are the work of the author. Measurements in drawings by the author are in metres. This dissertation contains plans and drawings which are best viewed digitally. ii Acknowledgements I would like to express my thanks to the following individuals: • Dr Adam Menuge at the Department of Building History, University of Cambridge for his support and encouragement during my studies in his role as Course Director, and for his helpful guidance and comments on early drafts of this dissertation as my Supervisor. • Dr Debbie Pullinger at Wolfson College, Cambridge for her support and encouragement as College Tutor to part-time students. -

Hertfordshire

Local Government Boundary Commission For England Report No. 390 LOCAL GOVERSKHTT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR E CHAIRMAN Sir Nicholas Morrison KC3 DEPUTY CRAIHKAU Mr J M Hankin M5MBERS Lady Borden Mr J T Brocktank Mr R S Thornton CBE. DL Mr D P Harrison Professor G E Cherry To the. Rt Hon.William Whitelaw, CH KG MP Secretary of State for the Home Department PROPOSALS FOR THE FUTURE SLiKTORAL AKHAIIG-S-iZNTS TOR THE COUNTY OF HERTFORDSHIRE 1. The last Order under Section 51 of the Local Government Act 1972 in relation to electoral arrangements for districts in the county of Hertfordshire was made' on 29 November 1978. As required by Section 63 and Schedule 9 of the Act we have now reviewed the electoral arrangements for that county, using the procedures we had set out in our Report No 6. 2. We informed the Hertfordshire County Council in a consultation letter dated 30 April 1979 that we proposed to conduct the review, and sent copies of the lettei to all local authorities and parish meetings in the county, to the MPs representing the constituencies concerned, to the headquarters of the main political parties and to the editors both of local newspauers circulating in the county and of the local government press. Notices in the local press announced the start of the review and invited comments from"members of the public and from interested bodies. 3. On 20 September 1979 the County Council submitted to us a draft scheme in which they suggested 77 electoral divisions for the county, each returning one member in accordance with Section 6(2)(a) of the Act.