Exploring the Three Cs in Sub-Roman Baldock Author: Keith J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BALDOCK, BYGRAVE and CLOTHALL NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN Design Guidelines

BALDOCK, BYGRAVE AND CLOTHALL NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN Design Guidelines March 2019 Quality information Project role Name Position Action summary Signature Date Qualifying body Michael Bingham Baldock , Bygrave and Clothall Review 17.12.2018 Planning Group Director / QA Ben Castell Director Finalisation 9.01.2019 Researcher Niltay Satchell Principal Urban Designer Research, site 9.01.2019 visit, drawings Blerta Dino Urban Designer Project Coordinator Mary Kucharska Project Coordinator Review 12.01.2019 This document has been prepared by AECOM Limited for the sole use of our client (the “Client”) and in accordance with generally accepted consultancy principles, the budget for fees and the terms of reference agreed between AECOM Limited and the Client. Any information provided by third parties and referred to herein has not been checked or verified by AECOM Limited, unless otherwise expressly stated in the document. No third party may rely upon this document without the prior and express written agreement of AECOM Limited. Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................................6 1.1. Background ..........................................................................................................................................................................................................6 1.2. Purpose of this document ............................................................................................................................................................................6 -

Hertfordshire Archaeology and History Hertfordshire Archaeology And

Hertfordshire Archaeology and History Hertfordshire Archaeology and History is the Society’s Journal. It is published in partnership with the East Herts Archaeological Society. We will have stock of the current (Vol. 17) and recent editions (Vols. 12-16) on sale at the conference at the following prices: • Volume 17: £12.00 as a ‘conference special’ price (normally £20.00); £5.00 to SAHAAS members • Volume 14 combined with the Sopwell Excavation Supplement: £7.00, or £5.00 each when sold separately • All other volumes: £5.00 Older volumes are also available at £5.00. If you see any of interest in the following contents listing, please email [email protected] by 11am on Friday 28 June and we will ensure stock is available at the conference to peruse and purchase. Please note: copies of some older volumes may be ex libris but otherwise in good condition. Volume 11 is out of stock. Copies of the Supplement to Volume 15 will not be available at the conference. If you have any general questions about the Journal, please email Christine McDermott via [email protected]. June 2019 Herts Archaeology and History - list of articles Please note: Volume 11 is out of stock; the Supplement to Volume 15 is not available at the conference Title Authors Pub Date Vol Pages Two Prehistoric Axes from Welwyn Garden City Fitzpatrick-Matthews, K 2009-15 17 1-5 A Late Bronze Age & Medieval site at Stocks Golf Hunn, J 2009-15 17 7-34 Course, Aldbury A Middle Iron Age Roundhouse and later Remains Grassam, A 2009-15 17 35-54 at Manor Estate, -

Baldock Radio Station Royston Road Baldock Herts SG7 6SH Mobile

ML2-005-04 Baldock Radio Station Royston Road Baldock Herts SG7 6SH Mobile Phone Base-Station Audit Audit Site: St Edmunds Catholic School Nelson Road Twickenham Middlesex TW2 7BB Work Perfomed by Distribution List James Loughlin 3G measurements Lloyd Tailby 1 Field Manager & Report Mrs R Murphy 1 Mike Reynolds 3G measurements Field Officer JP 1 JP 2G measurements Technical Manager 1 T.I. Officer & 2G Report Case/Year file 2 1 ML2-005-04 The Office of Communications (Ofcom) took over the functions of the Radiocommunications Agency, the Independent Television Commission, and the Radio Authority (as well as the Office of Telecommunications and the Broadcasting Standards Commission) on 29th December 2003. Ofcom is located at Riverside House, 2a Southwalk Bridge Road, London SE1 9HA. Tel: 020 7981 3000. Website: www.ofcom.org.uk Baldock Radio Station forms part of the Operations Group of Ofcom. The station address remains at Royston Road, Baldock, Hertfordshire SG7 6SH. Tel: 01462 428500, Fax: 01462 428510 2 ML2-005-04 Report Summary As the radio spectrum is continually changing, these measurements can only provide information on the radio frequency (RF) conditions for the specific locations at the time of the survey. The Office of Communications (Ofcom), originally the Radiocommunications Agency performed this survey of the RF emission environment in the vicinity of the site of St Edmunds Catholic School on 4th February 2004. Both second generation (2G) and third generation (3G) base station emissions were measured separately and the signal levels combined to calculate the Total Band Exposure as detailed below. The table, sorted in descending order of signal level, summarises the total results obtained at each measurement location. -

West of Tring Hertfordshire (Local Allocation 5)

Archaeological Services & Consultancy Ltd ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT STAGE 1: DESK-BASED ASSESSMENT: LAND AT ICKNIELD WAY WEST OF TRING HERTFORDSHIRE (LOCAL ALLOCATION 5) NGR: SP 9099 1126 on behalf of Dacorum Borough Council Jonathan Hunn BA PhD FSA MIfA July 2013 ASC: 1605/DHI/LA5 Letchworth House Chesney Wold, Bleak Hall Milton Keynes MK6 1NE Tel: 01908 608989 Fax: 01908 605700 Email: [email protected] Website: www.archaeological-services.co.uk Icknield Way, Tring West, Hertfordshire Desk-based Assessment 1605/DHI Site Data ASC site code: DHI Project no: 1605 OASIS ref: n/a Event/Accession no: n/a County: Hertfordshire Village/Town: Tring Civil Parish: Tring NGR (to 8 figs): SP 9099 1126 Extent of site: 9.7 + 8.3ha (44.5 acres) Present use: Primary area is pasture; secondary area is arable Planning proposal: Housing development Local Planning Authority: Dacorum Borough Council Planning application ref/date: Pre-planning Date of assessment: May 18th 2013 Client: Dacorum Borough Council Civic Centre Marlowes Hemel Hempstead Hertfordshire HP1 1HH Contact name: Mike Emett (CALA Homes) Internal Quality Check Primary Author: Jonathan Hunn Date: 18th May 2013 Revisions: David Fell Date: 04 July 2013 Edited/Checked By: Date: 11th June 2013 © Archaeological Services & Consultancy Ltd No part of this document is to be copied in any way without prior written consent. Every effort is made to provide detailed and accurate information. However, Archaeological Services & Consultancy Ltd cannot be held responsible for errors or inaccuracies within this report. © Ordnance Survey maps reproduced with the sanction of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. -

Polling Station List

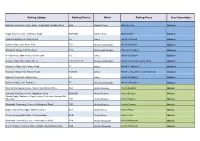

Polling Station Polling District Ward Polling Place Area Committee Baldock Community Centre, Large / Small Halls, Simpson Drive AAA Baldock Town Baldock Town Baldock Tapps Garden Centre, Wallington Road ABA,ABB Baldock East Baldock East Baldock Ashwell Parish Room, Swan Street FA Arbury Parish of Ashwell Baldock Sandon Village Hall, Payne End FAA Weston and Sandon Parish of Sandon Baldock Wallington Village Hall, The Street FCC Weston and Sandon Paish of Wallington Baldock The Old Forge, Manor Farm, Church Lane FD Arbury Parish of Bygrave Baldock Weston Village Hall, Maiden Street FDD, FDD1, FE Weston and Sandon Parishes of Weston and Clothall Baldock Hinxworth Village Hall, Francis Road FI Arbury Parish of Hinxworth Baldock Newnham Village Hall, Ashwell Road FS1,FS2 Arbury Parishes of Caldecote and Newnham Baldock Radwell Village Hall, Radwell Lane FX Arbury Parish of Radwell Baldock Rushden Village Hall, Rushden FZ Weston and Sandon Parish of Rushden Baldock Westmill Community Centre, Rear of John Barker Place BAA Hitchin Oughton Hitchin Oughton Hitchin Catholic Parish Church Hall, Nightingale Road BBA,BBD Hitchin Bearton Hitchin Bearton Hitchin Hitchin Rugby Clubhouse, King Georges Recreation Ground, Old Hale Way BBB Hitchin Bearton Hitchin Bearton Hitchin Walsworth Community Centre, 88 Woolgrove Road BBC Hitchin Bearton Hitchin Bearton Hitchin Baptist Church Hall, Upper Tilehouse Street BCA Hitchin Priory Hitchin Priory Hitchin St Johns Community Centre, St Johns Road BCB Hitchin Priory Hitchin Priory Hitchin Walsworth Community Centre, 88 Woolgrove Road BDA Hitchin Walsworth Hitchin Walsworth Hitchin New Testament Church of God, Hampden Road/Willian Road BDB Hitchin Walsworth Hitchin Walsworth Hitchin Polling Station Polling District Ward Polling Place Area Committee St Michaels Community Centre, St Michaels Road BDC,BDD Hitchin Walsworth Hitchin Walsworth Hitchin Benslow Music Trust- Fieldfares, Benslow Lane BEA Hitchin Highbury Hitchin Highbury Hitchin Whitehill J.M. -

Herts Archaeology -- Contents

Hertfordshire Archaeology and History contents From the 1880s until 1961 research by members of the SAHAAS was published in the Society’s Transactions. As part of an extensive project, digitised copies of the Transactions have been published on our website. Click here for further information: https://www.stalbanshistory.org/category/publications/transactions-1883-1961 Since 1968 members' research has appeared in Hertfordshire Archaeology published in partnership with the East Herts Archaeological Society. From Volume 14 the name was changed to Hertfordshire Archaeology and History. The contents from Volume 1 (1968) to Volume 18 (2016-2019) are listed below. If you have any questions about the journal, please email [email protected]. 1 Volume 1 1968 Foreword 1 The Date of Saint Alban John Morris, B.A., Ph.D. 9 Excavations in Verulam Hills Field, St Albans, 1963-4 Ilid E Anthony, M.A., Ph.D., F.S.A. 51 Investigation of a Belgic Occupation Site at A G Rook, B.Sc. Crookhams, Welwyn Garden City 66 The Ermine Street at Cheshunt, Herts. G R Gillam 68 Sidelights on Brasses in Herts. Churches, XXXI: R J Busby Furneaux Pelham 76 The Peryents of Hertfordshire Henry W Gray 89 Decorated Brick Window Lintels Gordon Moodey 92 The Building of St Albans Town Hall, 1829-31 H C F Lansberry, M.A., Ph.D. 98 Some Evidence of Two Mesolithic Sites at Bishop's A V B Gibson Stortford 103 A late Bronze Age and Romano-British Site at Thorley Wing-Commander T W Ellcock, M.B.E. Hill 110 Hertfordshire Drawings of Thomas Fisher Lieut-Col. -

Club Together Their Garden City Properties

27 31 13 47 17 57 23 Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of all information included in the guide. Please contact any groups in advance to ensure 2 information is still accurate. 3 HERITAGE ADVISORY CENTRE DISCOVER Letchwor th THE ARTS FREE occasional dance meeting spaces for community clubs music Chat to the team about making changes and groups during to your home. offi ce hours fi lm Open Monday to Friday from 10am to 3pm. visual arts 43 Station Road Letchworth Garden City, SG6 3BQ theatre 01462 476017 [email protected] 4 5 DISCOVER THE ARTS DISCOVER THE ARTS BALDOCK MIDNIGHT BRITTON SCHOOL OF GARDEN CITY SAMBA MORRIS PERFORMING ARTS Rehearsing and practising samba Practising and performing morris Dance and musical theatre training. dancing. dancing for ages 14 and over. Every Tuesday to Saturday during Every Tuesday evening. Every Tuesday evening from term-time, sessions at various St Francis’ College, Broadway, January to July and September times. SG6 3PJ to December. Wilbury Hall, Bedford Road, gardencitysamba.com The Scout HQ, Park Drive, SG6 4DU, Icknield Centre, 07527 561755 or Baldock, SG7 6EN SG6 1EF or Lordship Farm School, 07786 638712 baldockmidnightmorris.org.uk Fouracres, SG6 3UF Baldock & Letchworth Blues, 01462 339438 brittonschool.co.uk Folk and Roots Club GARDEN CITY SINGERS info@baldock 07973 308741 midnightmorris.org.uk [email protected] Singing a wide variety of songs in BALDOCK & three and four part harmonies. LETCHWORTH BLUES, Every Wednesday evening, from FOLK AND ROOTS CLUB BEAT REPUBLIC CITY CHORUS January to July and September ACADEMY OF DANCE to December. -

Beacon View Walk the Beacon View Walk Chilterns: Visit Or Call 01844 355500

The Greyhound, Wiggingtom This is one of a series of walks through the Chilterns Area of Outstanding Natural Chilterns Country The Greyhound in Wigginton is a friendly traditional village inn Beauty (AONB). with a wide selection of real ales, wines and fine food. En-suite accommodation is also available and the pub has disabled access. Cyclists and walkers are welcome. Phone 01442 824631. The Chilterns Conservation Board works to conserve the natural www.greyhoundtring.co.uk beauty of the Chilterns and to increase public understanding and enjoyment of them. There are many other walks and rides in the Beacon View Walk The Beacon View Walk Chilterns: Visit www.chilternsaonb.org or call 01844 355500. The Beacon View walk goes through Tring Park on King Charles Walk Description: Long: 6.5m (10.5km) Visit www.chilternsociety.org.uk or call 01494 771250 for Ride. Tring Park is a historic landscape with remnants of an Short: 2m (3km) early 18th century landscape. It is managed by the Woodland information on the Chiltern Society's walk programme, to obtain Trust and is open access for walkers. Cyclists and horse riders Chiltern Society footpath maps or to join the Society. Walk Time: Long: allow 2 1/2 hours can enjoy the Park by using the King Charles Ride. The Park has Short: allow 1 hour woodland areas, chalk grassland and affords fine views of Tring and Ivinghoe Beacon, a prominent grassy hill. Pub, restaurant and B&B in Wigginton: Start /Finish: The Greyhound, Chesham Road Criss-crossed by historic transport routes, this area has been The Greyhound, Wigginton: a friendly, traditional village inn Wigginton, Herts well used by travellers since the first settlements appeared in with a wide selection of real ales, wines and fine food. -

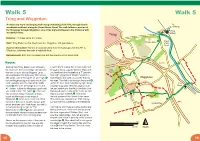

Tring and Wigginton

Walk 5 Walk 5 Tring and Wigginton A varied and more challenging walk along undulating chalk hills, through beech to woodlands and back along the Grand Union Canal. The walk follows a section of Aldbury the Ridgeway through Wigginton, one of the highest villages in the Chilterns with P Tring wonderful views. 9 Tring Station Distance: 4¼ miles (allow 2¼ hours) 1 Grand Pendley Manor Start: Tring Station (or the Greyhound Inn, Wigginton, with permission). Union Canal Access Information: There is a moderate climb from the footbridge over the A41 to Wigginton, otherwise the route is relatively level. Refreshments: Both the Cow Roast pub and the Greyhound Inn serve food. 2 Route: A4251 8 Starting from Tring Station, turn left along Lewin's Farm. Follow this across fields and the road over the canal bridge and take the through a wood, (signed Chiltern Way) until Tring Park first turn on your left into Beggars Lane, you reach another footpath at a ‘T’ junction. 3 also signposted the Ridgeway. After about Turn right (signposted ‘Public Footpath to 4 200 yards, take the footpath on your right. 1 Cow Roast’) and down a concrete track to Wigginton Follow Ridgeway signs to reach the A4251 the road. Turn left to go through the tunnel 6 road, crossing over the road at the traffic under the A41, then immediately right along Cow 7 island 2 then over the bridge to cross the a byway to go past Tinker's Lodge on your Roast A41 below. Follow the Ridgeway uphill until left and continue to the A4251 and the Cow PH you reach a lane 'The Twist'; 3 cross over Roast pub, once a stop-off for cattle on their and continue along a footpath until you way to London markets. -

Hertfordshire. Mil 311 Machinists

TRADES DIREC'rORY.] HERTFORDSHIRE. MIL 311 MACHINISTS. Richardson Charles William, AmweIl Burgin Hy. Flaunden, Chesham S.O Argent James, Victoria st. St. Albans End! Ware ,Bush John, ~uckeridge, Ware Barham Charles L. West alley, Hitchin SedgWIck Mrs. Mary Ann & Co. The ChalIen EdWIn,StansteadAbbots, Ware Dearman WilIiam, Walkern, Stevenage Brewery, Watford . & South wha;rf, ClaphamF.Flamstead end,WalthamCrss Everard Josph. High rd. Waltham Cross Praed street, Paddmgton W.; Stat~on Cox George, Church street, Baldock Hamilton John Buntingford R SO road, West Croydon; SurhIton hIlI, CoxshaIl John, Park la. Waltham Cl'06S Hodgson Nath~n, Stevenage .. Surbiton &Brunswick pI. nth.Brighton FordD.Heronsgate,~ckmanswth.R.S.() Horton WiIliam, 62 High st. Watford Sell R:obert Henry, New road, Ware Ford p.H~r?nsga~,Rlckmanswth.R.S.() Howard George WaIters Britannia ter- Sherrdl' Arthur Jas. North rd. Hatfield Fuller WIlliam, CIllocks farm, Hertford. race Royston' Simpson & Co. High street, Baldock road, Hoddesdon Ivory Henry, Stevenage Taylor H. A. & D. D~ne street, Bishop's George Mrs. Elizabeth, Park street, St. Moore George E. 203 High st. Watford Stortford & Sawbndgeworth R:S.O, Stephens, St. Alb~ns Oliver Archibald Thomas Wandon end Taylor John & Son, Wharf, BIShop s Haden Thomas, Codtcote, Welwyn King's Walden Hitchi~ , Stortford Hale Mrs. Elizabeth, London rd. HertS Park William A~hwell Baldock Taylor Henry AIgernon & Douglas, Harris John, Appleby street, Cheshnut, Smith In. Wheathampstead, St. Albans High street, 'Yare Waltham Cross . Starkey Alfred John, Mill gn. Hatfield ~ard Henry, HIgh street, Ware Mansell Edward, Hadha~road, Bishop's Tregaskiss A.Watton-at-Stone, Hertford" ard Henry, The Wharf. -

Hertfordshire

Archaeological Investigations Project 2003 Post-Determination & Non-Planning Related Projects Eastern Region HERTFORDSHIRE Broxbourne 3/324 (E.26.O004) TL 36070895 EN11 8SH HIGH LEIGH FARM, BOX LANE High Leigh Farm, Box Lane, Hoddesdon, Hertfordshire Turner, I & Roberts, B Hertford : Archaeological Solutions, 2003, 14pp, figs, tabs Work undertaken by: Archaeological Solutions An archaeological watching brief was carried out on the site. No archaeology was observed. [Au(abr)] Dacorum 3/325 (E.26.O014) TL 06301640 AL3 8LQ 55 HIGH STREET, MARKYATE 55 High Street, Markyate, Hertfordshire Grant, J Hertford : Archaeological Solutions, 2003, 12pp, figs, tabs Work undertaken by: Archaeological Solutions An archaeological watching brief was carried out on the site. No archaeology was observed. [Au(abr)] 3/326 (E.26.O007) SP 96601030 HP4 1LE 8 COW ROAST 8 Cow Roast, Hertfordshire Hun, J Milton Keynes : Archaeological Services & Consultancy Ltd., 2003, 18pp, figs, tabs, refs Work undertaken by: Archaeological Services & Consultancy Ltd An archaeological watching brief was carried out groundworks for an extension to the house. A Romano-British occupation deposit was identified, containing pottery and iron slag. [Au(abr)] Archaeological periods represented: RO 3/327 (E.26.O006) SP 97440983 HP4 1LP GORESIDE FARM, NORTHCHURCH COMMON Goreside Farm, Northchurch Common, Berkhamsted Hunn, J Milton Keynes : Archaeological Services & Consultancy Ltd., 2003, 17pp, figs, tabs, refs Work undertaken by: Archaeological Services & Consultancy Ltd An archaeological watching brief was carried out on the site. No archaeology was observed. [Au(abr)] 3/328 (E.26.O005) SP 96361010 HP4 1LA NORCOTT COURT FARM, COW ROAST Norcott Court Farm, Cow Roast, Berkhamsted Hunn, J Milton Keynes : Archaeological Services & Consultancy Ltd., 2003, 22pp, colour pls, figs, tabs, refs Work undertaken by: Archaeological Services & Consultancy Ltd Monitoring was carried out on topsoil stripping for a temporary track way. -

Baldock Conservation Area Character Statement Draws on All These Factors to Create a Document That Records Comprehensively What Is ‘Special’ About the Area

NORTH HERTFORDSHIRE DISTRICT COUNCIL CHARACTER STATEMENT FOR BALDOCK CONSERVATION AREA (17th June 2003) 2 CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction 5 2.0 Location and Landscape Setting 7 3.0 Origins and Development 7 4.0 The Architectural and Historic Character of the 11 Buildings 5.0 Prevalent and Traditional Materials 13 6.0 The Contribution made by Green Spaces and Trees 15 7.0 Townscape Analysis 15 7.1 Introduction 15 7.2 The High Street 15 7.3 Whitehorse Street 20 7.4 Hitchin Street 24 7.5 Church Street 26 7.6 Park Street 29 8.0 Negative Features 31 9.0 Neutral or Negative Areas for Improvement 32 10.0 Summary of Special Characteristics 34 Glossary of Terms 37 Bibliography 39 3 4 1.0 INTRODUCTION What are Conservation Areas? 1.1 Conservation areas are very special places. Each one is of ‘special’ architectural or historic importance, with a character or appearance to be preserved or enhanced. Conservation areas are an important part of our heritage and each one is unique and irreplaceable. Their special qualities appeal to visitors and are attractive places to live and work. They provide a strong sense of place and are part of the familiar and local cherished scene. 1.2 Conservation areas are based around groups of buildings, and the spaces created between and around them. It is the quality and interest of areas, rather than that of individual buildings that are the prime consideration in identifying conservation areas. Each area is different and has a distinct character and appearance. Conservation Area Legislation, Government Guidance and Development Plans Conservation Area Legislation 1.3 Conservation areas are defined in The Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 as ‘areas of special architectural or historic interest, the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance’.