The Cemeteries of Roman Baldock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consolidated List of Definitive Map (DM) Changes Since DM2015 To

Consolidated list of Definitive Map (DM) changes since DM2015 to Dec 19 Rosalinde Emrys-Roberts (to June 18) and Richard Cuthbert (Dec 18 on), of the Herts County Council Rights of Way Service, report on progress with the Definitive Map. In December 2015, we sealed our latest Definitive Map—’DM2015’. In future, the working copy of the Definitive Map available on the web will be updated more regularly – probably on a monthly basis. Since that consolidation, the following routes have been added or existing rights of way changed. They are listed by District and the status of the route and its location described. Broxbourne A footpath has been recorded in Cheshunt, leading south from Ashdown Crescent to Cadmore Lane. The footpath crossing the railway west of Dobb’s Weir in Hoddesdon has been diverted over a new railway bridge with steps. In Goffs Oak, a footpath has been recorded connecting Cuffley Hill (just east of Jones Road) northwards to The Drive. Dacorum A new footpath has been dedicated in Kings Langley, leading south east from Footpath 5 alongside the A41 to Footpath 1, adjacent to junction 20 of the M25. A new footpath has been recorded in Potton End, leading north east from Brown’s Spring through woodland to connect with Nettledon & Potton End Footpath 31. The width of the footpath leading from Wilstone Green to Wilstone reservoir has been recorded following enforcement action. In Kings Langley a path round the perimeter of the field north of Lady Meadow has been recorded as a public footpath (Kings Langley 47). East Herts The bridleway crossing the A120 Bishop’s Stortford Bypass south of Wickham Hall is now correctly shown in the Definitive Map records. -

BALDOCK, BYGRAVE and CLOTHALL NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN Design Guidelines

BALDOCK, BYGRAVE AND CLOTHALL NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN Design Guidelines March 2019 Quality information Project role Name Position Action summary Signature Date Qualifying body Michael Bingham Baldock , Bygrave and Clothall Review 17.12.2018 Planning Group Director / QA Ben Castell Director Finalisation 9.01.2019 Researcher Niltay Satchell Principal Urban Designer Research, site 9.01.2019 visit, drawings Blerta Dino Urban Designer Project Coordinator Mary Kucharska Project Coordinator Review 12.01.2019 This document has been prepared by AECOM Limited for the sole use of our client (the “Client”) and in accordance with generally accepted consultancy principles, the budget for fees and the terms of reference agreed between AECOM Limited and the Client. Any information provided by third parties and referred to herein has not been checked or verified by AECOM Limited, unless otherwise expressly stated in the document. No third party may rely upon this document without the prior and express written agreement of AECOM Limited. Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................................6 1.1. Background ..........................................................................................................................................................................................................6 1.2. Purpose of this document ............................................................................................................................................................................6 -

Baldock Radio Station Royston Road Baldock Herts SG7 6SH Mobile

ML2-005-04 Baldock Radio Station Royston Road Baldock Herts SG7 6SH Mobile Phone Base-Station Audit Audit Site: St Edmunds Catholic School Nelson Road Twickenham Middlesex TW2 7BB Work Perfomed by Distribution List James Loughlin 3G measurements Lloyd Tailby 1 Field Manager & Report Mrs R Murphy 1 Mike Reynolds 3G measurements Field Officer JP 1 JP 2G measurements Technical Manager 1 T.I. Officer & 2G Report Case/Year file 2 1 ML2-005-04 The Office of Communications (Ofcom) took over the functions of the Radiocommunications Agency, the Independent Television Commission, and the Radio Authority (as well as the Office of Telecommunications and the Broadcasting Standards Commission) on 29th December 2003. Ofcom is located at Riverside House, 2a Southwalk Bridge Road, London SE1 9HA. Tel: 020 7981 3000. Website: www.ofcom.org.uk Baldock Radio Station forms part of the Operations Group of Ofcom. The station address remains at Royston Road, Baldock, Hertfordshire SG7 6SH. Tel: 01462 428500, Fax: 01462 428510 2 ML2-005-04 Report Summary As the radio spectrum is continually changing, these measurements can only provide information on the radio frequency (RF) conditions for the specific locations at the time of the survey. The Office of Communications (Ofcom), originally the Radiocommunications Agency performed this survey of the RF emission environment in the vicinity of the site of St Edmunds Catholic School on 4th February 2004. Both second generation (2G) and third generation (3G) base station emissions were measured separately and the signal levels combined to calculate the Total Band Exposure as detailed below. The table, sorted in descending order of signal level, summarises the total results obtained at each measurement location. -

Hertfordshire Archives and Local Studies

GB 0046 D/ECb Hertfordshire Archives and Local Studies This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NRA 13977 The National Archives HERTFORDSHIRE RECORD OFFICE D/ECb Deeds of the Koddesdon Brewery and a number of licensed houses owned or leased by the brevors. Deposited by Messrs. Boulton Sons and Sandeman for the Cannon Brewery. Inventory compiled: LAccession 162] March 1968 D/ECb Introduction This collection consists of deeds incident to the conveyance of the vhole of the Hoddesdon Brewery and all its licensed houses in 1866 and titl e deeds of some of those houses and of others that were acquired later. The expansion of Hoddesdon Brewery dates from its purchase by William Whittingstall from Rene Briand in 1781. From that date til l his death in 1803, rfhittingstall systematically enlarged the brewery*s commercial outlets by buying up a number of public houses in the surrounding district. Messrs. John Christie and George Cathrow bought the property from Vhittingstall's executors and at the death of Cathrow in 1842 it was sold privately to a new partnership of Messrs. Peter Christie, John Back and Robert Hunt. After Peter Christie's death and when 3ack and Hunt had retired to their country estates, the firm was conveyed in 1866 to Charles Peter Christie. On his death in 1898 it was turned into a public company which 30 years later was absorbed by the Cannon Brewery of London, later controlled by Taylor, Valker and Co. and now by the Ind Coope combine. -

23 July 2021

NORTH HERTFORDSHIRE DISTRICT COUNCIL WEEK ENDING 23 JULY 2021 MEMBERS’ INFORMATION Topic Page News and information 1-4 CCTV Reports - Pre-Agenda, Agenda and Decision sheets 5-16 Planning consultations - Planning applications received & decisions 17-33 Press releases 34-35 Produced by the Communications Team. Any comments, suggestions or contributions should be sent to the Communications Team at [email protected] Page 1 of 35 NEWS AND INFORMATION AGENDA & REPORTS PUBLISHED WEEK COMMENCING 19 JULY 2021 None FORTHCOMING MEETINGS WEEK COMMENCING 26 JULY 2021 None CHAIR’S ENGAGEMENTS WEEK COMMENCING 24 JULY 2021 Date Event Location None VICE-CHAIR’S ENGAGEMENTS WEEK COMMENCING 24 JULY 2021 Date Event Location None OTHER EVENTS WEEK COMMENCING 24 JULY 2021 Date Event Location None Page 2 of 35 REGULATORY SERVICES MEMBERS INFORMATION NOTE North Hertfordshire Local Plan Examination Update The latest consultation on the new Local Plan for the District closed in June 2021. Members of the public and other interested parties were invited to comment upon the latest proposed changes to the Plan and a number of supporting documents. The consultation followed the further hearing public sessions held by the Inspector between November 2020 and February 2021. The Council received approximately 670 responses to the consultation. These contained approximately 1,500 distinct representations on the documents and detailed proposed changes that were consulted upon. The Inspector has now given the go-ahead for the responses to be made public. The independent Programme Officer, who helps administer the Examination, has asked for the website to be updated so that people know that the representations are available to view and to add the following text: The Inspector will be reading and considering all the representations that have been submitted. -

Berry, Grosvenor’S Sister William ETTY (1787-1849)

Clarence in Much Hadham and his nephew Grosvenor – a mystery solved By Marcus Bicknell, November 2019. Copyright © 2019 Marcus Bicknell www.clarencebicknell.com [email protected] Clarence’s sketches of Much Hadham I have been haunted for 20 years by two nice sketches by Clarence Bicknell of Much Hadham, a quiet village in Hertfordshire, northeast of London and now under the departing flight path of Stansted airport. One sketch is of the windmill at Much Hadham (below right) and the other of The Palace at Much Hadham, the latter titled by Clarence in a hand-styled font, a cross between 12th century medieval and contemporary arts-and-crafts (on page 3 below). Both are dated 1889; he visited Much Hadham in July of that year. But we never knew, until today, why Clarence went there. He had moved to Bordighera ten years earlier, so this trip was not a casual one, not just touristic. He would have had an objective. Thanks to the keen interest of a present inhabitant of Much Hadham, a descendant of Charles Adams and a regular follower of Clarence Bicknell’s Facebook page, we have the answer. Much Hadham was the home of Ada Berry née Bicknell (1831-1911), Clarence's favourite sibling, 11 years his elder. He visited her in London and Kent throughout his life. Our Much Hadham source also made the link with Ada’s son Grosvenor Berry who lived and farmed in the area for there for 65 years. Clarence Bicknell - Grosvenor Berry Marcus Bicknell 2019 1 Ada Berry née Bicknell Ada Bicknell married Edward Berry 1 (senior) in 1857. -

Cory Cottage, Mackerye End, Harpenden, Hertfordshire

Cory Cottage, Mackerye End, Harpenden, Hertfordshire Cory Cottage Outside A short driveway leads to a large, paved parking Mackerye End, Harpenden area directly in front of the cottage. A detached AL5 5DR double garage also provides parking space for two cars. A paved patio space surrounded by An attractive semi-detached cottage mature hedges sits at the side of the house, in an enviable semi-rural location on while the rear garden features a large well-kept lawn, flower beds and countryside views. the outskirts of Harpenden, with far reaching countryside views. Location Mackerye End is a pretty semi-rural hamlet Wheathampstead 2.2 miles, Harpenden station on the fringes of Harpenden in Hertfordshire. 2.2 miles (London St Pancras 27 minutes), Nearby Harpenden has a thriving High Street Harpenden 2.4 miles, St Albans 6.9 miles, and a comprehensive range of shops, including Welwyn Garden City 7 miles, M1 (J10) 7 miles, Sainsbury’s, Waitrose and a Marks and Spencer. Hemel Hempstead 10 miles, Central London 30 It also features an excellent selection of miles restaurants, cafes and independent stores. For an even greater choice, St Albans and Welwyn Reception hall | Sitting room | Family room Garden City are only a short drive away. Kitchen/breakfast room | Cloakroom | Principal bedroom with en suite bathroom | 3 Further Harpenden benefits from a number of bedrooms | Family bathroom | Garage | Garden outstanding state schools, Katherine Warrington EPC rating E 0.5 miles, Sir John Lawes 1.9 miles and St Georges 2.4 miles. Independent schools nearby The property include Beechwood Park, Aldwickbury Prep Cory Cottage is a charming semi-detached School and St. -

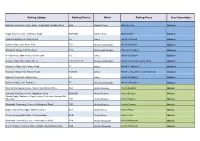

Polling Station List

Polling Station Polling District Ward Polling Place Area Committee Baldock Community Centre, Large / Small Halls, Simpson Drive AAA Baldock Town Baldock Town Baldock Tapps Garden Centre, Wallington Road ABA,ABB Baldock East Baldock East Baldock Ashwell Parish Room, Swan Street FA Arbury Parish of Ashwell Baldock Sandon Village Hall, Payne End FAA Weston and Sandon Parish of Sandon Baldock Wallington Village Hall, The Street FCC Weston and Sandon Paish of Wallington Baldock The Old Forge, Manor Farm, Church Lane FD Arbury Parish of Bygrave Baldock Weston Village Hall, Maiden Street FDD, FDD1, FE Weston and Sandon Parishes of Weston and Clothall Baldock Hinxworth Village Hall, Francis Road FI Arbury Parish of Hinxworth Baldock Newnham Village Hall, Ashwell Road FS1,FS2 Arbury Parishes of Caldecote and Newnham Baldock Radwell Village Hall, Radwell Lane FX Arbury Parish of Radwell Baldock Rushden Village Hall, Rushden FZ Weston and Sandon Parish of Rushden Baldock Westmill Community Centre, Rear of John Barker Place BAA Hitchin Oughton Hitchin Oughton Hitchin Catholic Parish Church Hall, Nightingale Road BBA,BBD Hitchin Bearton Hitchin Bearton Hitchin Hitchin Rugby Clubhouse, King Georges Recreation Ground, Old Hale Way BBB Hitchin Bearton Hitchin Bearton Hitchin Walsworth Community Centre, 88 Woolgrove Road BBC Hitchin Bearton Hitchin Bearton Hitchin Baptist Church Hall, Upper Tilehouse Street BCA Hitchin Priory Hitchin Priory Hitchin St Johns Community Centre, St Johns Road BCB Hitchin Priory Hitchin Priory Hitchin Walsworth Community Centre, 88 Woolgrove Road BDA Hitchin Walsworth Hitchin Walsworth Hitchin New Testament Church of God, Hampden Road/Willian Road BDB Hitchin Walsworth Hitchin Walsworth Hitchin Polling Station Polling District Ward Polling Place Area Committee St Michaels Community Centre, St Michaels Road BDC,BDD Hitchin Walsworth Hitchin Walsworth Hitchin Benslow Music Trust- Fieldfares, Benslow Lane BEA Hitchin Highbury Hitchin Highbury Hitchin Whitehill J.M. -

Club Together Their Garden City Properties

27 31 13 47 17 57 23 Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of all information included in the guide. Please contact any groups in advance to ensure 2 information is still accurate. 3 HERITAGE ADVISORY CENTRE DISCOVER Letchwor th THE ARTS FREE occasional dance meeting spaces for community clubs music Chat to the team about making changes and groups during to your home. offi ce hours fi lm Open Monday to Friday from 10am to 3pm. visual arts 43 Station Road Letchworth Garden City, SG6 3BQ theatre 01462 476017 [email protected] 4 5 DISCOVER THE ARTS DISCOVER THE ARTS BALDOCK MIDNIGHT BRITTON SCHOOL OF GARDEN CITY SAMBA MORRIS PERFORMING ARTS Rehearsing and practising samba Practising and performing morris Dance and musical theatre training. dancing. dancing for ages 14 and over. Every Tuesday to Saturday during Every Tuesday evening. Every Tuesday evening from term-time, sessions at various St Francis’ College, Broadway, January to July and September times. SG6 3PJ to December. Wilbury Hall, Bedford Road, gardencitysamba.com The Scout HQ, Park Drive, SG6 4DU, Icknield Centre, 07527 561755 or Baldock, SG7 6EN SG6 1EF or Lordship Farm School, 07786 638712 baldockmidnightmorris.org.uk Fouracres, SG6 3UF Baldock & Letchworth Blues, 01462 339438 brittonschool.co.uk Folk and Roots Club GARDEN CITY SINGERS info@baldock 07973 308741 midnightmorris.org.uk [email protected] Singing a wide variety of songs in BALDOCK & three and four part harmonies. LETCHWORTH BLUES, Every Wednesday evening, from FOLK AND ROOTS CLUB BEAT REPUBLIC CITY CHORUS January to July and September ACADEMY OF DANCE to December. -

Hertfordshire. Ware

DIRECTORY. ] HERTFORDSHIRE. WARE. 197 OFFICUL ESTA.BLISHMEXTS, LOCAL INSTITt'TIO:KS &C. "Post, M. O. &; T. 0., S. B., Express Delivery &; Annuity I desdon district, Henry Blackaby, Stanstead Abbots; 1f, Insurance Office.-Geo~ge Price, postmaster, High I ""Yare district, 'Yalter Rutter, Milton road. Ware .street. Letters received from London at 9 a.m. 4.3°, Vaccination Officer, J. P. Stephenson. Baldock st. Ware 12 &; 1.15 p.m.; dispatched at 10.30 a.m. II.sO a.m. Medical Officers &; Public Vaccinators, 1'10. I district, 1.10, 4.15 &; 10.30 p.m.; sundays. delivered at 7.30 James Bryce M.D., C.M. Puckeridge; No. 2 district• .a.m.; dispatched at 8.20 &; 10.20 p.m. Four d,e- Henry Osborn Fawcett Butcher, High street, Ware; liveries each day, at 8 &; 10.20 a.m. &; 4.30 &; 7.5 p.m :Ko. 3 district, Alexander James Boyd B.A., M.D., B.Ch. Sub-Post Office, Ware Side.-George Thake, postmaster. Ware; No. 4 district, William Blundell Willans Letters through Ware at 8.20 a.m. &; 12 noon; dis- L.R.C.P.Edin. Much Hadham; No. 5 district, Howard patched at 9.15 a.m. &; 6 p.m. Postal orders are issued Hawkins L.R.C.P.Edin. Broxbourne; No. 6 &; 8 dis- here, but not paid tricts, A. J. Bisdee, Hoddesdon; :Ko. 7 district. F. R. "1'here are three Pillar Boxes, New road, .Amwell End &; B. Hinde, Sawbridgeworth Baldock street, which are cleared as under; no col- Superintendent Registrar, George Henry Gisby, Baldock lection on sundays for pillar boxes; Baldock street, street, ""Vare; deputy, James P. -

Exploring the Three Cs in Sub-Roman Baldock Author: Keith J

Paper Information: Title: Collapse, Change or Continuity? Exploring the three Cs in sub-Roman Baldock Author: Keith J. Fitzpatrick-Matthews Pages: 132–148 DOI: http://doi.org/10.16995/TRAC2009_132_148 Publication Date: 25 March 2010 Volume Information: Moore, A., Taylor, G., Harris, E., Girdwood, P., and Shipley, L. (eds.) (2010) TRAC 2009: Proceedings of the Nineteenth Annual Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference, Michigan and Southampton 2009. Oxford: Oxbow Books. Copyright and Hardcopy Editions: The following paper was originally published in print format by Oxbow Books for TRAC. Hard copy editions of this volume may still be available, and can be purchased direct from Oxbow at http://www.oxbowbooks.com. TRAC has now made this paper available as Open Access through an agreement with the publisher. Copyright remains with TRAC and the individual author(s), and all use or quotation of this paper and/or its contents must be acknowledged. This paper was released in digital Open Access format in March 2015. Collapse, Change or Continuity? Exploring the three Cs in sub-Roman Baldock Keith J. Fitzpatrick-Matthews Introduction The ‘small towns’ of Roman Britain are the under-theorised ‘Cinderellas’ of the province’s archaeology yet, at the same time, they should be regarded as the great success story of Roman rule. They were the dominant class of urban settlement, with a huge variety of forms, presumably reflecting different social, economic and political roles. Yet studies of the fifth- century collapse of urban civilisation in Britain focus almost exclusively on the major cities and ignore the ‘small towns’. However, because of their diversity, they have the potential to offer unique insights into the processes that operated from the early fifth century on, to transform Roman Britain into the early medieval successor states. -

Hertfordshire Archives and Local Studies

GB0046 D/EB 1089 Hertfordshire Archives and Local Studies This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NRA 15824 The National Archives HERTFORDSHIRE RECORD OFFICE D/EB 1089 Title deeds and other documents relating to properties, mainly public houses, of Pryor, Reid and Co, Ltd.. brewers of Hatfield; deposited by Messrs Markby Stevart and Vadeson, per British Records Association, August 1962 [Part of Accession 940] Inventory compiled March 1971 D/EB1089 Introductory Note The bundling of this collection of deeds has been left, as far as has been practical, as it was when it was received from the British Records Association. However, it is apparent from notes on the wrappers or envelopes that some of the bundles originally contained other deeds which have at some time been removed. TITLE DEEDS D/EB1089 [including tenancy agreements and schedules of deeds] Various Parishos in Herts, and Bods. *T1 The Plough High Street Codicote; 4 1897-1907 The Hoops Perry Green, Much Hadham; The Pisherman, Pishers Green, Stevenage; the White House, with cottages, Wareside, Ware; the Pox and Duck and the Woolpack, Clifton, Bods.; the Prince of Wales, Luton, Beds, [deeds connected with the liquidation and reconstruction of Pryor, Reid and Co. Ltd] T2 Schedule of deeds relating to the 1 1919 Waggon and Horses, Hemel Hempstead and, in Beds., the Pox and Duck, Clifton, Five Bells, Houghton Regis, Blue Lion, Pour Horseshoes, Queen1s Arms, Railway Inn, World's End and No. 21 Havelock Road, Luton, Woolpack, Shefford Little Berkhampstead, Hatfield, Hertford, Northaw.