The Landscapes of Eynhallow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Prose Supplement 7 (2011) [Click for Pdf]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1876/prose-supplement-7-2011-click-for-pdf-31876.webp)

Prose Supplement 7 (2011) [Click for Pdf]

PS edited by Raymond Friel and Richard Price number 7 Ten Richard Price It’s ten years since I started Painted, spoken. Looking back over the issues of the magazine, two of the central patterns were there from the word go. They’re plain as day in the title: the fluid yet directing edge poetry shares with the visual arts, and, somewhere so far in the other direction it’s almost the same thing, the porous edge poetry shares with sound or performance, so porous you can hear it in its hollows. Although the magazine grew out of serial offences in little magazineship, the first impulse was to be quite different formally from Gairfish, Verse, and Southfields, each of which had placed a premium on explanation, on prose engagement, and on the analysis of the cultural traditions from which the poems they published either appeared to emerge or through which, whatever their actual origins, they could be understood. Painted, spoken would be much more tight-lipped, a gallery without the instant contextualisation demanded by an educational agenda (perhaps rightly in a public situation, but a mixed model is surely better than a constant ‘tell-us-what-to-think’ approach and the public isn’t always best served by conventional teaching). Instead, poems in Painted, spoken would take their bearings from what individual readers brought to the texts ‘themselves’ - because readers are never really alone - and also from the association of texts with each other, in a particular issue and across issues. The magazine went on its laconic way for several years until a different perspective began to open up, a crystal started to solidify, whatever metaphor you’d care to use for time-lapse comprehension (oh there’s another one): in management-speak, significant change impressed on the strategy and the strategy needed to change. -

Cruising the ISLANDS of ORKNEY

Cruising THE ISLANDS OF ORKNEY his brief guide has been produced to help the cruising visitor create an enjoyable visit to TTour islands, it is by no means exhaustive and only mentions the main and generally obvious anchorages that can be found on charts. Some of the welcoming pubs, hotels and other attractions close to the harbour or mooring are suggested for your entertainment, however much more awaits to be explored afloat and many other delights can be discovered ashore. Each individual island that makes up the archipelago offers a different experience ashore and you should consult “Visit Orkney” and other local guides for information. Orkney waters, if treated with respect, should offer no worries for the experienced sailor and will present no greater problem than cruising elsewhere in the UK. Tides, although strong in some parts, are predictable and can be used to great advantage; passage making is a delight with the current in your favour but can present a challenge when against. The old cruising guides for Orkney waters preached doom for the seafarer who entered where “Dragons and Sea Serpents lie”. This hails from the days of little or no engine power aboard the average sailing vessel and the frequent lack of wind amongst tidal islands; admittedly a worrying combination when you’ve nothing but a scrap of canvas for power and a small anchor for brakes! Consult the charts, tidal guides and sailing directions and don’t be afraid to ask! You will find red “Visitor Mooring” buoys in various locations, these are removed annually over the winter and are well maintained and can cope with boats up to 20 tons (or more in settled weather). -

Scottish Birds

SCOTTISH BIRDS THE JOURNAL OF THE SCOTTISH ORNITHOLOGISTS' CLUB Volume 5 No. 7 AUTUMN 1969 Price 5s earl ZeissofW.Germany presents the revolutionary 10x40 B Dialyt The first slim-line 10 x 40B binoculars, with the special Zeiss eyepieces giving the same field of view for spectacle wearers and the naked eye alike. Keep the eyecups flat for spectacles or sun glasses. Snap them up for the naked eye. Brilliant Zeiss optics, no external moving parts-a veritable jewel of a binocular. Just arrived from Germany There is now also a new, much shorter B x 30B Dialyt, height only 4. 1/Bth". See this miniature marvel at your dealer today. Latest Zeiss binocular catalogue and the name of your nearest stockist from: Degenhardt & Co. Ltd., Carl Zeiss House, 31 /36 Foley Street, London W1 P BAP. 01-6368050 (15 lines) . ~ - ~ Dlegenhardt BIRDS & BIG GAME SAFARI departing 4th March and visiting Murchison Falls N.P., Treetops, Samburu G.R., Lake Naivisha, Laka Nakuru, Nairobi N.P., Kenya Coast, Lake Manyara N.P., Ngorongoro Crater, Arutha N.P. accompanied by John G. WUliams, Esq., who was for 111 years the Curator of Ornithology at the National (formerly Coryndon) Museum, Nairobi WILDLIFE SAFARIS visiting Queen Elizabeth N.P., Murchison Falls N.P., Nairobi N.P., Tsavo N.P., Lake Manyara N.P., Ngorongoro Crater, Serengetl N.P., Mara G.R., Lake Naivasha, Treetops. Departures : 30th Jan.; 13th, 20th Feb.; 6th, 13th Mar.; 24th July; 25th Sept.; 16th Oct. Price: 485 Gns. Each 21-day Safari is accompanied by a Guest Lecturer, in cluding- Hugh B. -

Of Orkn Y 2015 Information and Travel Guide to the Smaller Islands of Orkney

The Islands of ORKN Y 2015 information and travel guide to the smaller islands of Orkney For up to date Orkney information visit www.visitorkney.com • www.orkney.com • www.discover-orkney.com The Islands of ORKN Y Approximate driving times From Kirkwall and Stromness to Ferry Terminals at: • Tingwall 30 mins • Houton 20 mins From Stromness to Kirkwall Airport • 40 mins From Kirkwall to Airport • 10 mins The Islands of looking towards evie and eynhallow from the knowe of yarso on rousay - drew kennedy 1 Contents Contents Out among the isles . 2-5 will be happy to assist you find the most At catching fish I am so speedy economic travel arrangements: A big black scarfie fromEDAY . 6-9 www.visitscotland.com/orkney If you want something with real good looks You can’t go wrong with FLOTTA fleuks . 10-13 There’s not quite such a wondrous thing as a beautiful young GRAEMSAY gosling . 14-17 To take the head off all their big talk Just pay attention to the wise HOY hawk . 14-17 The Countryside Code All stand to the side and reveal Please • close all gates you open. Use From far NORTH RONALDSAY a seal . 18-21 stiles when possible • do not light fires When feeling low or down in the dumps • keep to paths and tracks Just bake some EGILSAY burstin lumps . 22-25 • do not let your dog worry grazing animals You can say what you like, I don’t care • keep mountain bikes on the For I’m a beautiful ROUSAY mare . -

Layout 1 Copy

STACK ROCK 2020 An illustrated guide to sea stack climbing in the UK & Ireland - Old Harry - - Old Man of Stoer - - Am Buachaille - - The Maiden - - The Old Man of Hoy - - over 200 more - Edition I - version 1 - 13th March 1994. Web Edition - version 1 - December 1996. Web Edition - version 2 - January 1998. Edition 2 - version 3 - January 2002. Edition 3 - version 1 - May 2019. Edition 4 - version 1 - January 2020. Compiler Chris Mellor, 4 Barnfield Avenue, Shirley, Croydon, Surrey, CR0 8SE. Tel: 0208 662 1176 – E-mail: [email protected]. Send in amendments, corrections and queries by e-mail. ISBN - 1-899098-05-4 Acknowledgements Denis Crampton for enduring several discussions in which the concept of this book was developed. Also Duncan Hornby for information on Dorset’s Old Harry stacks and Mick Fowler for much help with some of his southern and northern stack attacks. Mike Vetterlein contributed indirectly as have Rick Cummins of Rock Addiction, Rab Anderson and Bruce Kerr. Andy Long from Lerwick, Shetland. has contributed directly with a lot of the hard information about Shetland. Thanks are also due to Margaret of the Alpine Club library for assistance in looking up old journals. In late 1996 Ben Linton, Ed Lynch-Bell and Ian Brodrick undertook the mammoth scanning and OCR exercise needed to transfer the paper text back into computer form after the original electronic version was lost in a disk crash. This was done in order to create a world-wide web version of the guide. Mike Caine of the Manx Fell and Rock Club then helped with route information from his Manx climbing web site. -

Erin and Alban

A READY REFERENCE SKETCH OF ERIN AND ALBAN WITH SOME ANNALS OF A BRANCH OF A WEST HIGHLAND FAMILY SARAH A. McCANDLESS CONTENTS. INTRODUCTION. PART I CHAPTER I PRE-HISTORIC PEOPLE OF BRITAIN 1. The Stone Age--Periods 2. The Bronze Age 3. The Iron Age 4. The Turanians 5. The Aryans and Branches 6. The Celto CHAPTER II FIRST HISTORICAL MENTION OF BRITAIN 1. Greeks 2. Phoenicians 3. Romans CHAPTER III COLONIZATION PE}RIODS OF ERIN, TRADITIONS 1. British 2. Irish: 1. Partholon 2. Nemhidh 3. Firbolg 4. Tuatha de Danan 5. Miledh 6. Creuthnigh 7. Physical CharacteriEtics of the Colonists 8. Period of Ollaimh Fodhla n ·'· Cadroc's Tradition 10. Pictish Tradition CHAPTER IV ERIN FROM THE 5TH TO 15TH CENTURY 1. 5th to 8th, Christianity-Results 2. 9th to 12th, Danish Invasions :0. 12th. Tribes and Families 4. 1169-1175, Anglo-Norman Conquest 5. Condition under Anglo-Norman Rule CHAPTER V LEGENDARY HISTORY OF ALBAN 1. Irish sources 2. Nemedians in Alban 3. Firbolg and Tuatha de Danan 4. Milesians in Alban 5. Creuthnigh in Alban 6. Two Landmarks 7. Three pagan kings of Erin in Alban II CONTENTS CHAPTER VI AUTHENTIC HISTORY BEGINS 1. Battle of Ocha, 478 A. D. 2. Dalaradia, 498 A. D. 3. Connection between Erin and Alban CHAPTER VII ROMAN CAMPAIGNS IN BRITAIN (55 B.C.-410 A.D.) 1. Caesar's Campaigns, 54-55 B.C. 2. Agricola's Campaigns, 78-86 A.D. 3. Hadrian's Campaigns, 120 A.D. 4. Severus' Campaigns, 208 A.D. 5. State of Britain During 150 Years after SeveTus 6. -

The Arms of the Scottish Bishoprics

UC-NRLF B 2 7=13 fi57 BERKELEY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORN'A \o Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/armsofscottishbiOOIyonrich /be R K E L E Y LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORN'A h THE ARMS OF THE SCOTTISH BISHOPRICS. THE ARMS OF THE SCOTTISH BISHOPRICS BY Rev. W. T. LYON. M.A.. F.S.A. (Scot] WITH A FOREWORD BY The Most Revd. W. J. F. ROBBERDS, D.D.. Bishop of Brechin, and Primus of the Episcopal Church in Scotland. ILLUSTRATED BY A. C. CROLL MURRAY. Selkirk : The Scottish Chronicle" Offices. 1917. Co — V. PREFACE. The following chapters appeared in the pages of " The Scottish Chronicle " in 1915 and 1916, and it is owing to the courtesy of the Proprietor and Editor that they are now republished in book form. Their original publication in the pages of a Church newspaper will explain something of the lines on which the book is fashioned. The articles were written to explain and to describe the origin and de\elopment of the Armorial Bearings of the ancient Dioceses of Scotland. These Coats of arms are, and have been more or less con- tinuously, used by the Scottish Episcopal Church since they came into use in the middle of the 17th century, though whether the disestablished Church has a right to their use or not is a vexed question. Fox-Davies holds that the Church of Ireland and the Episcopal Chuich in Scotland lost their diocesan Coats of Arms on disestablishment, and that the Welsh Church will suffer the same loss when the Disestablishment Act comes into operation ( Public Arms). -

Orkney Greylag Goose Survey Report 2015

The abundance and distribution of British Greylag Geese in Orkney, August 2015 A report by the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust to Scottish Natural Heritage Carl Mitchell 1, Alan Leitch 2, & Eric Meek 3 November 2015 1 The Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust, Slimbridge, Gloucester, GL2 7BT 2 The Willows, Finstown, Orkney, KY17, 2EJ 3 Dashwood, 66 Main Street, Alford, Aberdeenshire, AB33 8AA 1 © The Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder. This publication should be cited as: Mitchell, C., A.J. Leitch & E. Meek. 2015. The abundance and distribution of British Greylag Geese in Orkney, August 2015. Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust Report, Slimbridge. 16pp. Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust Slimbridge Gloucester GL2 7BT T 01453 891900 F 01453 890827 E [email protected] Reg. Charity no. 1030884 England & Wales, SC039410 Scotland 2 Contents Summary ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Methods ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Field counts ...................................................................................................................................... -

The Kirk in the Garden of Evie

THE KIRK IN THE GARDEN OF EVIE A Thumbnail Sketch of the History of the Church in Evie Trevor G Hunt Minister of the linked Churches of Evie, Firth and Rendall, Orkney First Published by Evie Kirk Session Evie, Orkney. 1987 Republished 1996 ComPrint, Orkney 908056 Forward to the 1987 Publication This brief history was compiled for the centenary of the present Evie Church building and I am indebted to all who have helped me in this work. I am especially indebted to the Kirk’s present Session Clerk, William Wood of Aikerness, who furnished useful local information, searched through old Session Minutes, and compiled the list of ministers for Appendix 3. Alastair Marwick of Whitemire, Clerk to the Board, supplied a good deal of literature, obtained a copy of the Title Deeds, gained access to the “Kirk aboon the Hill”, and conducted a tour (even across fields in his car) to various sites. He also contributed valuable local information and I am grateful for all his support. Thanks are also due to Margaret Halcro of Lower Crowrar, Rendall, for information about her name sake, and to the Moars of Crook, Rendall, for other Halcro family details. And to Sheila Lyon (Hestwall, Sandwick), who contributed information about Margaret Halcro (of the seventeenth century!). TREVOR G HUNT Finstown Manse March 1987 Foreword to the 1996 Publication Nearly ten years on seemed a good time to make this history available again, and to use the advances in computer technology to improve its appearance and to make one or two minor corrections.. I was also anxious to include the text of the history as a page on the Evie, Firth and Rendall Churches’ Internet site for reference and, since revision was necessary to do this, it was an opportunity to republish in printed form. -

Representations of Scotland in Edwin Morgan's Poetry

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2002 Representations of Scotland in Edwin Morgan's poetry Theresa Fernandez Mendoza-Kovich Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Mendoza-Kovich, Theresa Fernandez, "Representations of Scotland in Edwin Morgan's poetry" (2002). Theses Digitization Project. 2157. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2157 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REPRESENTATIONS OF SCOTLAND IN EDWIN MORGAN'S POETRY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English Composition by Theresa Fernandez Mendoza-Kovich September 2002 REPRESENTATIONS OF SCOTLAND IN EDWIN MORGAN'S POETRY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Theresa Fernandez Mendoza-Kovich September 2002 Approved by: Renee PrqSon, Chair, English Date Margarep Doane Cyrrchia Cotter ABSTRACT This thesis is an examination of the poetry of Edwin Morgan. It is a cultural analysis of Morgan's poetry as representation of the Scottish people. ' Morgan's poetry represents the Scottish people as determined and persistent in dealing with life's adversities while maintaining hope in a better future This hope, according to Morgan, is largely associated with the advent of technology and the more modern landscape of his native Glasgow. -

ST MAGNUS: an EXPLORATION of HIS SAINTHOOD William P

ST MAGNUS: AN EXPLORATION OF HIS SAINTHOOD William P. L. Thomson When the editors of New Dictionary of National Biography were recently discussing ways in which the new edition is different from the old, they re marked that one of the changes is in the treatment of saints: The lives [of saints] are no longer viewed as straightforward stories with an unfor tunate, but easily discounted, tendency to exaggeration, but may now be valued more for what they reveal about their authors, or about the milieu in which they were written, than for any information they contain about their ostensible subjects (DNB 1998). This is a good note on which to begin the exploration of Magnus's saint hood. We need to concern ourselves with the historical Magnus - and Magnus has a better historical basis than many saints - but equally we need to explore the ways people have perceived his sainthood and often manipulated it for their own purposes. The Divided Earldom The great Earl Thorfinn was dead by I 066 and his earldom was shared by his two sons (fig. I). It was a weakness of the earldom that it was divisible among heirs, and the joint rule of Paul and Erlend gave rise to a split which resulted not just in THOR FINN PAUL I ERLEND Kali I I HAKON MAGNUS Gunnhild m Kol I ,- I Maddad m Margaret HARALD PAUL II ROGNVALD E. of Atholl I HARALD MADDADSSON Ingirid I Harald the Younger Fig. 1. The Earls of Orkney. 46 the martyrdom of Magnus, but in feuds which still continued three and four generations later when Orkneyinga Saga was written (c.1200). -

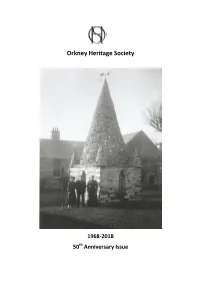

2018 50Th Anniversary Issue

Orkney Heritage Society 1968-2018 50th Anniversary Issue Objectives of the Orkney Heritage Society The aims of the Society are to promote and encourage the following objectives by charitable means: 1. To stimulate public interest in, and care for the beauty, history and character of Orkney. 2. To encourage the preservation, development and improvement of features of general public amenity or historical interest. 3. To encourage high standards of architecture and town planning in Orkney. 4. To pursue these ends by means of meetings, exhibitions, lectures, conferences, publicity and promotion of schemes of a charitable nature. New members are always welcome To learn more about the society and its ongoing work, check out the regularly updated website at www.orkneycommunities.co.uk/ohs or contact us at Orkney Heritage Society PO Box No. 6220 Kirkwall Orkney KW15 9AD Front Cover: Robert Garden and his wife, Margaret Jolly, along with one of their daughters standing next to the newly re-built Groatie Hoose. It got its name from the many shells, including ‘groatie buckies’, decorating the tower. Note the weather vane showing some of Garden’s floating shops. Photo gifted by Mrs Catherine Dinnie, granddaughter of Robert Garden. 1 Orkney Heritage Society Committee 2018 President: Sandy Firth, Edan, Berstane Road, Kirkwall, KW15 1NA [email protected] Vice President: Sheena Wenham, Withacot, Holm [email protected] Chairman: Spencer Rosie, 7 Park Loan, Kirkwall, KW15 1PU [email protected] Vice Chairman: David Murdoch, 13