King James's Daemonologie: the Evolution of the Concept Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 400Th Anniversary of the Lancashire Witch-Trials: Commemoration and Its Meaning in 2012

The 400th Anniversary of the Lancashire Witch-Trials: Commemoration and its Meaning in 2012. Todd Andrew Bridges A thesis submitted for the degree of M.A.D. History 2016. Department of History The University of Essex 27 June 2016 1 Contents Abbreviations p. 3 Acknowledgements p. 4 Introduction: p. 5 Commemorating witch-trials: Lancashire 2012 Chapter One: p. 16 The 1612 Witch trials and the Potts Pamphlet Chapter Two: p. 31 Commemoration of the Lancashire witch-trials before 2012 Chapter Three: p. 56 Planning the events of 2012: key organisations and people Chapter Four: p. 81 Analysing the events of 2012 Conclusion: p. 140 Was 2012 a success? The Lancashire Witches: p. 150 Maps: p. 153 Primary Sources: p. 155 Bibliography: p. 159 2 Abbreviations GC Green Close Studios LCC Lancashire County Council LW 400 Lancashire Witches 400 Programme LW Walk Lancashire Witches Walk to Lancaster PBC Pendle Borough Council PST Pendle Sculpture Trail RPC Roughlee Parish Council 3 Acknowledgement Dr Alison Rowlands was my supervisor while completing my Masters by Dissertation for History and I am honoured to have such a dedicated person supervising me throughout my course of study. I gratefully acknowledge Dr Rowlands for her assistance, advice, and support in all matters of research and interpretation. Dr Rowland’s enthusiasm for her subject is extremely motivating and I am thankful to have such an encouraging person for a supervisor. I should also like to thank Lisa Willis for her kind support and guidance throughout my degree, and I appreciate her providing me with the materials that were needed in order to progress with my research and for realising how important this research project was for me. -

The Witch-Cult in Western Europe, by Margaret Alice Murray This Ebook Is for the Use of Anyone Anywhere at No Cost and with Almost No Restrictions Whatsoever

20411-0 The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Witch-cult in Western Europe, by Margaret Alice Murray This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Witch-cult in Western Europe A Study in Anthropology Author: Margaret Alice Murray Release Date: January 22, 2007 [EBook #20411] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE WITCH-CULT IN WESTERN EUROPE *** Produced by Michael Ciesielski, Irma THE WITCH-CULT IN WESTERN EUROPE _A Study in Anthropology_ BY MARGARET ALICE MURRAY OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS 1921 Oxford University Press _London Edinburgh Glasgow Copenhagen New York Toronto Melbourne Cape Town Bombay Calcutta Madras Shanghai_ Humphrey Milford Publisher to the UNIVERSITY PREFACE The mass of existing material on this subject is so great that I have not attempted to make a survey of the whole of European 'Witchcraft', but have confined myself to an intensive study of the cult in Great Britain. In order, however, to obtain a clearer understanding of the ritual and beliefs I have had recourse to French and Flemish sources, as the cult appears to have been the same throughout Western Europe. The New England records are unfortunately not published _in extenso_; this is the more unfortunate as the extracts already given to the public occasionally throw light on some of the English practices. -

Criminalising Witchcraft

A Creative Connect International Publication 19 CRIMINALISING WITCHCRAFT Written by Bhavya Sharma* & Utkarsh Jain** * 3rd year BA LLB, Institute of Law, Nirma University, Ahmedabad ** 3rd year BA LLB, Institute of Law, Nirma University, Ahmedabad INTRODUCTION Witchcraft as a term means the belief in, and practice of, magical skills and abilities that are able to be exercised by individuals and certain social groups. These are practiced by witches. Witch is an English word gender specific which is confined to women only. Witch is generally attributed to the individuals who through sheer malice, consciously or subconsciously, use magical power to inflict all type of evil on their fellow humans. They usually bring disease; destroy property and misfortune and causes death, without any provocation to satisfy their inherent craving. Some cultures in the Province of South Africa believe that all the misfortunes and deaths are either due to the punishments by ancestors or by the evil spirits or witches. It is found that majority of the people in the provinces believes in witchcraft and therefore the existence of witches. It is considered that some people are born as witches. In some culture in the African Provinces it is believed that a baby born should be thrown against a wall and if the baby clings to the wall, he or she would become a witch afterwards. Many animals are also considered to be associated with the practice of witchcraft such as owls, cats, snakes, bats, baboons, pole- carts. Some of the material articles related with witchcraft includes mirror, blades, brown bread, whirlwinds, traditional dishes, plates, saucers, traditional horns which are blown at nights, etc. -

Layout 1 Copy

STACK ROCK 2020 An illustrated guide to sea stack climbing in the UK & Ireland - Old Harry - - Old Man of Stoer - - Am Buachaille - - The Maiden - - The Old Man of Hoy - - over 200 more - Edition I - version 1 - 13th March 1994. Web Edition - version 1 - December 1996. Web Edition - version 2 - January 1998. Edition 2 - version 3 - January 2002. Edition 3 - version 1 - May 2019. Edition 4 - version 1 - January 2020. Compiler Chris Mellor, 4 Barnfield Avenue, Shirley, Croydon, Surrey, CR0 8SE. Tel: 0208 662 1176 – E-mail: [email protected]. Send in amendments, corrections and queries by e-mail. ISBN - 1-899098-05-4 Acknowledgements Denis Crampton for enduring several discussions in which the concept of this book was developed. Also Duncan Hornby for information on Dorset’s Old Harry stacks and Mick Fowler for much help with some of his southern and northern stack attacks. Mike Vetterlein contributed indirectly as have Rick Cummins of Rock Addiction, Rab Anderson and Bruce Kerr. Andy Long from Lerwick, Shetland. has contributed directly with a lot of the hard information about Shetland. Thanks are also due to Margaret of the Alpine Club library for assistance in looking up old journals. In late 1996 Ben Linton, Ed Lynch-Bell and Ian Brodrick undertook the mammoth scanning and OCR exercise needed to transfer the paper text back into computer form after the original electronic version was lost in a disk crash. This was done in order to create a world-wide web version of the guide. Mike Caine of the Manx Fell and Rock Club then helped with route information from his Manx climbing web site. -

A Comprehensive Look at the Salem Witch Mania of 1692 Ashley Layhew

The Devil’s in the Details: A Comprehensive Look at the Salem Witch Mania of 1692 __________ Ashley Layhew Nine-year-old Betty Parris began to convulse, seize, and scream gibber- ish in the winter of 1692. The doctor pronounced her bewitched when he could find no medical reason for her actions. Five other girls began ex- hibiting the same symptoms: auditory and visual hallucinations, fevers, nausea, diarrhea, epileptic fits, screaming, complaints of being bitten, poked, pinched, and slapped, as well as coma-like states and catatonic states. Beseeching their Creator to ease the suffering of the “afflicted,” the Puritans of Salem Village held a day of fasting and prayer. A relative of Betty’s father, Samuel Parris, suggested a folk cure, in which the urine of the afflicted girls was taken and made into a cake. The villagers fed the cake to a dog, as dogs were believed to be the evil helpers of witches. This did not work, however, and the girls were pressed to name the peo- ple who were hurting them.1 The girls accused Tituba, a Caribbean slave who worked in the home of Parris, of being the culprit. They also accused two other women: Sarah Good and Sarah Osbourne. The girls, all between the ages of nine and sixteen, began to accuse their neighbors of bewitching them, saying that three women came to them and used their “spectres” to hurt them. The girls would scream, cry, and mimic the behaviors of the accused when they had to face them in court. They named many more over the course of the next eight months; the “bewitched” youth accused a total of one hundred and forty four individuals of being witches, with thirty sev- en of those executed following a trial. -

3 Die Materialität Des Teufels Und Ihre Wir- Kung Auf Hexenverfolgung Und Hexenprozeß in Ausgewählten Europäischen Ländern Und in Den Neuenglischen Kolonien

3 Die Materialität des Teufels und ihre Wir- kung auf Hexenverfolgung und Hexenprozeß in ausgewählten europäischen Ländern und in den neuenglischen Kolonien Kernpunkt vieler Hexenprozesse der frühen Neuzeit in Europa und in den neuenglischen Kolonien war die Frage nach der materiellen Existenz des Teu- fels und ihr Nachweis. Teufelspakt, Teufelsbuhlschaft und Hexenflug - alles Elemente des Volks- aberglaubens - waren für einen großen Teil der Hexenprozesse zentrale An- klagepunkte in den Gerichtsverfahren und trugen sowohl in Europa als auch in den neuenglischen Kolonien zu einer Intensivierung der Hexenverfolgung in der frühen Neuzeit bei. Martin Pott bezeichnet diese Elemente des Volksaberglaubens als „Penta- gramm des Hexenwahns“. Er sieht den Hexenglauben als ausgefeilte Theorie, deren Inhalte im Begriff des Teufelspaktes kulminieren.196 Seit Menschengedenken gehörte die Vorstellung einer den Menschen nicht immer freundlich gesinnten, real existenten Parallelwelt zum alltäglichen Le- ben. Einerseits war sie in vorchristlicher Zeit eine durchaus wertfreie Möglich- keit, unerklärliche Erlebnisse verständlich zu machen, andererseits diente sie später dem Christentum als spirituelles Gegengewicht zum göttlichen Wir- ken. Vor allem in kontinentaleuropäischen Ländern, wie zum Beispiel in Deutschland, gewann das Übernatürliche in der frühneuzeitlichen Hexen- verfolgung an Bedeutung. Die Verhandlung von Hexenanklagen vor Gericht mußte dieser Entwicklung Rechnung tragen. Zeugenaussagen und Geständ- nisse der Angeklagten, welche die Existenz des -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

Macbeth Informational Text: the Real Story

Name ________________________________________ Period _______ Macbeth Informational Text: The Real Story It is interesting to note that Shakespeare‘s play Macbeth was based loosely on true stories about real people. In fact, it is believed that Shakespeare wrote the play for King James I and VI, who was king of both England and Scotland at the time. Allegedly using the Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland (1587) by Raphael Holinshed as his source of information, Shakespeare set out to create a realistic fictional drama based on a true story. The real King Duncan I (Donnchad mac Crínáin), nicknamed ―the sick‖ was the King of Scotland (called Alba) from 1034 to 1040. He was the grandson of Malcolm II, who was killed in battle in 1034. Duncan had two sons, Malcolm III, and Donald III. According to records, Duncan was young and weak and was seen as a terrible and ineffective leader. His ascension to the throne at age 17 caused turmoil in the family, as the kingship was to have alternated between the two branches of the royal line. Many believed his cousin, Macbeth (Mac Bethad mac Findlaích), should have had claim to the throne through his mother. This caused strife in the family, which would continue for hundreds of years. After Duncan was killed in battle by Macbeth in 1040, Macbeth took the throne and became King of Scotland. Macbeth reigned successfully for 17 years, and he was said to be a powerful and strong leader. However, Duncan‘s son Malcolm wanted revenge against Macbeth, and felt that he should have inherited the throne after his father‘s death. -

Scotland: Bruce 286

Scotland: Bruce 286 Scotland: Bruce Robert the Bruce “Robert I (1274 – 1329) the Bruce holds an honored place in Scottish history as the king (1306 – 1329) who resisted the English and freed Scotland from their rule. He hailed from the Bruce family, one of several who vied for the Scottish throne in the 1200s. His grandfather, also named Robert the Bruce, had been an unsuccessful claimant to the Scottish throne in 1290. Robert I Bruce became earl of Carrick in 1292 at the age of 18, later becoming lord of Annandale and of the Bruce territories in England when his father died in 1304. “In 1296, Robert pledged his loyalty to King Edward I of England, but the following year he joined the struggle for national independence. He fought at his father’s side when the latter tried to depose the Scottish king, John Baliol. Baliol’s fall opened the way for fierce political infighting. In 1306, Robert quarreled with and eventually murdered the Scottish patriot John Comyn, Lord of Badenoch, in their struggle for leadership. Robert claimed the throne and traveled to Scone where he was crowned king on March 27, 1306, in open defiance of King Edward. “A few months later the English defeated Robert’s forces at Methven. Robert fled to the west, taking refuge on the island of Rathlin off the coast of Ireland. Edward then confiscated Bruce property, punished Robert’s followers, and executed his three brothers. A legend has Robert learning courage and perseverance from a determined spider he watched during his exile. “Robert returned to Scotland in 1307 and won a victory at Loudon Hill. -

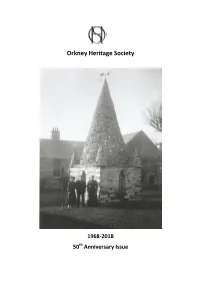

2018 50Th Anniversary Issue

Orkney Heritage Society 1968-2018 50th Anniversary Issue Objectives of the Orkney Heritage Society The aims of the Society are to promote and encourage the following objectives by charitable means: 1. To stimulate public interest in, and care for the beauty, history and character of Orkney. 2. To encourage the preservation, development and improvement of features of general public amenity or historical interest. 3. To encourage high standards of architecture and town planning in Orkney. 4. To pursue these ends by means of meetings, exhibitions, lectures, conferences, publicity and promotion of schemes of a charitable nature. New members are always welcome To learn more about the society and its ongoing work, check out the regularly updated website at www.orkneycommunities.co.uk/ohs or contact us at Orkney Heritage Society PO Box No. 6220 Kirkwall Orkney KW15 9AD Front Cover: Robert Garden and his wife, Margaret Jolly, along with one of their daughters standing next to the newly re-built Groatie Hoose. It got its name from the many shells, including ‘groatie buckies’, decorating the tower. Note the weather vane showing some of Garden’s floating shops. Photo gifted by Mrs Catherine Dinnie, granddaughter of Robert Garden. 1 Orkney Heritage Society Committee 2018 President: Sandy Firth, Edan, Berstane Road, Kirkwall, KW15 1NA [email protected] Vice President: Sheena Wenham, Withacot, Holm [email protected] Chairman: Spencer Rosie, 7 Park Loan, Kirkwall, KW15 1PU [email protected] Vice Chairman: David Murdoch, 13 -

Family Tree Maker

Ancestors of Ulysses Simpson Grant Generation No. 1 1. President Ulysses Simpson Grant, born 27 Apr 1822 in Point Pleasant, Clermont Co., OH; died 23 Jul 1885 in Mount McGregor, Saratoga Co., NY. He was the son of 2. Jesse Root Grant and 3. Hannah Simpson. He married (1) Julia Boggs Dent 22 Aug 1848. She was born 26 Jan 1826 in White Haven Plantation, St. Louis Co. MO, and died 14 Dec 1902 in Washington, D. C.. She was the daughter of "Colonel" Frederick Fayette Dent and Ellen Bray Wrenshall. Generation No. 2 2. Jesse Root Grant, born 23 Jan 1794 in Greensburg, Westmoreland Co., PA; died 29 Jan 1873 in Covington, Campbell Co., KY. He was the son of 4. Noah Grant III and 5. Rachel Kelley. He married 3. Hannah Simpson 24 Jun 1821 in The Simpson family home. 3. Hannah Simpson, born 23 Nov 1798 in Horsham, Philadelphia Co., PA; died 11 May 1883 in Jersey City, Coventry Co., NJ. She was the daughter of 6. John Simpson, Jr. and 7. Rebecca Weir. Children of Jesse Grant and Hannah Simpson are: 1 i. President Ulysses Simpson Grant, born 27 Apr 1822 in Point Pleasant, Clermont Co., OH; died 23 Jul 1885 in Mount McGregor, Saratoga Co., NY; married Julia Boggs Dent 22 Aug 1848. ii. Samuel Simpson Grant iii. Orville Grant iv. Clara Grant v. Virginia "Nellie" Grant vi. Mary Frances Grant Generation No. 3 4. Noah Grant III, born 20 Jun 1748; died 14 Feb 1819 in Maysville, Mason Co., KY. He was the son of 8. -

The Witch-Cult in Western Europe, by 1

The Witch-cult in Western Europe, by 1 The Witch-cult in Western Europe, by Margaret Alice Murray This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Witch-cult in Western Europe A Study in Anthropology Author: Margaret Alice Murray Release Date: January 22, 2007 [EBook #20411] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE WITCH-CULT IN WESTERN EUROPE *** Produced by Michael Ciesielski, Irma Špehar and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net THE WITCH-CULT IN WESTERN EUROPE A Study in Anthropology BY MARGARET ALICE MURRAY The Witch-cult in Western Europe, by 2 OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS 1921 Oxford University Press London Edinburgh Glasgow Copenhagen New York Toronto Melbourne Cape Town Bombay Calcutta Madras Shanghai Humphrey Milford Publisher to the UNIVERSITY PREFACE The mass of existing material on this subject is so great that I have not attempted to make a survey of the whole of European 'Witchcraft', but have confined myself to an intensive study of the cult in Great Britain. In order, however, to obtain a clearer understanding of the ritual and beliefs I have had recourse to French and Flemish sources, as the cult appears to have been the same throughout Western Europe. The New England records are unfortunately not published in extenso; this is the more unfortunate as the extracts already given to the public occasionally throw light on some of the English practices.