The 2020 General Election in Myanmar: a Time for Ethnic Reflection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

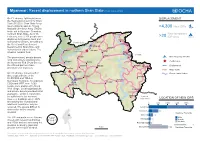

4,300 New Idps >20

Myanmar: Recent displacement in northern Shan State (as of 16 Feb 2016) On 7 February, fighting between DISPLACEMENT the Restoration Council for Shan State (RCSS) / Shan State Army South (SSA-S) and the Ta’ang >4,300 New IDPs National Liberation Army (TNLA) broke out in Kyaukme Township, northern Shan State. As of 16 Monekoe New temporary February, over 3,300 people were >20 IDP sites displaced to Kyaukme town and Konkyan surrounding villages, according to Kachin State Namhkan the Relief and Resettlement Laukkaing Mong Wee Department in Shan State and Tarmoenye humanitarian organizations. The Northern Mabein Lawt Naw Kutkai situation remains fluid. Shan State Hopang Hseni Kunlong CHINA The government, private donors, Manton Pan Lon New tempoary IDP sites local civil society organizations, Mongmit Conflict area the Myanmar Red Cross Society, Namtu the UN and partners have Namhsan Lashio Mongmao Pangwaun Displacement provided relief materials. Tawt San Major roads Mongngawt On 9 February, armed conflict Monglon Rivers / water bodies also erupted between the Hsipaw Namphan RCSS/SSA and TNLA in Kyaukme Tangyan Namhkam Township. According to Mongyai CSOs and WFP, over 1,000 Nawnghkio people were displaced to Mong Wee village. Local organisations Pangsang and private donors provided initial assistance, which is reported to be sufficient for the moment. Matman Eastern However, buildings where IDPs Shan State LOCATION OF NEW IDPS are staying are crowded and 0 500 1000 1500 2000 additional assistance may be required. The area is difficult to Kyaukme 2,400 access due to the security Kho Mone 520 situation. Kyaukme Township Mine Tin 220 The UN and partners are liaising Male closely with relevant authorities Monglon 110 Female No data and CSOs and are assessing the Pain Nal Kon 90 situation to identify gaps and provide further aid if needed. -

Important Facts About the 2015 General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation - Emref

Important Facts about the 2015 Myanmar General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation (EMReF) 2015 October Important Facts about the 2015 General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation - EMReF 1 Important Facts about the 2015 General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation - EMReF ENLIGHTENED MYANMAR RESEARCH ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ABSTRACT FOUNDATION (EMReF) This report is a product of the Information Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation EMReF is an accredited non-profit research Strategies for Societies in Transition program. (EMReF has been carrying out political-oriented organization dedicated to socioeconomic and This program is supported by United States studies since 2012. In 2013, EMReF published the political studies in order to provide information Agency for International Development Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010- and evidence-based recommendations for (USAID), Microsoft, the Bill & Melinda Gates 2012). Recently, EMReF studied The Record different stakeholders. EMReF has been Foundation, and the Tableau Foundation.The Keeping and Information Sharing System of extending its role in promoting evidence-based program is housed in the University of Pyithu Hluttaw (the People’s Parliament) and policy making, enhancing political awareness Washington's Henry M. Jackson School of shared the report to all stakeholders and the and participation for citizens and CSOs through International Studies and is run in collaboration public. Currently, EMReF has been regularly providing reliable and trustworthy information with the Technology & Social Change Group collecting some important data and information on political parties and elections, parliamentary (TASCHA) in the University of Washington’s on the elections and political parties. performances, and essential development Information School, and two partner policy issues. -

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Import Law Dekkhina and President U Win Myint Were and S: 25 of the District Detained

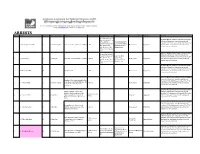

Current No. Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Address Remark Condition Superintendent Myanmar Military Seizes Power Kyi Lin of and Senior NLD leaders S: 8 of the Export Special Branch, including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Import Law Dekkhina and President U Win Myint were and S: 25 of the District detained. The NLD’s chief Natural Disaster Administrator ministers and ministers in the Management law, (S: 8 and 67), states and regions were also 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F General Aung San State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 Penal Code - Superintendent House Arrest Naypyitaw detained. 505(B), S: 67 of Myint Naing Arrested State Counselor Aung the (S: 25), U Soe San Suu Kyi has been charged in Telecommunicatio Soe Shwe (S: Rangoon on March 25 under ns Law, Official 505 –b), Section 3 of the Official Secrets Secret Act S:3 Superintendent Act. Aung Myo Lwin (S: 3) Myanmar Military Seizes Power S: 25 of the and Senior NLD leaders Natural Disaster including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi Superintendent Management law, and President U Win Myint were Myint Naing, Penal Code - detained. The NLD’s chief 2 (U) Win Myint M U Tun Kyin President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 Dekkhina House Arrest Naypyitaw 505(B), S: 67 of ministers and ministers in the District the states and regions were also Administrator Telecommunicatio detained. ns Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. -

Peace & Conflict Update – October 2017

PEACE & CONFLICT UPDATE – OCTOBER 2017 Updates archive: http://www.burmalink.org/peace-conflict-updates/ Updates archive: https://www.burmalink.org/peace-process-overview/ ACRONYM DICTIONARY AA Arakan Army ALP Arakan Liberation Party BA Burma Army (Tatmadaw) CSO Civil Society Organisation DASSK Daw Aung San Suu Kyi EAO Ethnic Armed Organisation FPNCC Federal Political Negotiation Consultative Committee IDP Internally Displaced Person KBC Karen Baptist Convention KIA Kachin Independence Arm, armed wing of the KIO KIO Kachin Independence Organization KNU Karen National Union MoU Memorandum of Understanding MNEC Mon National Education Committee MNHRC Myanmar National Human Rights Commission NCA Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (in name only, not inclusive and not nationwide) NLD National League for Democracy NRPC National Reconciliation and Peace Center PC Peace Commission PPST Peace Process Steering Committee (NCA negotiating body) SSPP/SSA-N Shan State Progress Party/Shan State Army (North) TNLA Ta'ang National Liberation Army UN United Nations UNFC United Nationalities Federal Council UPC Union Peace Conference UPDJC Union Peace Dialogue Joint Committee UWSA United Wa State Army 21CPC 21st Century Panglong Conference OCTOBER HIGHLIGHTS • Over 600,000 Rohingya have been displaced since the August 25 attacks and subsequent 'clearance operations' in Arakan (Rakhine). Talks of repatriation of Rohingya refugees between Burma and Bangladesh have stalled, and many Rohingya refugees reject the prospect of returning in the light of unresolved causes to the violence, and fears of ongoing abuse. • Displaced populations on the Thailand-Burma border face increasing challenges and humanitarian funding cuts. As of October 1, TBC has stopped distributing food aid to Shan IDP camps and the Ei Tu Hta Karen IDP camp. -

Reform in Myanmar: One Year On

Update Briefing Asia Briefing N°136 Jakarta/Brussels, 11 April 2012 Reform in Myanmar: One Year On mar hosts the South East Asia Games in 2013 and takes I. OVERVIEW over the chairmanship of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 2014. One year into the new semi-civilian government, Myanmar has implemented a wide-ranging set of reforms as it em- Reforming the economy is another major issue. While vital barks on a remarkable top-down transition from five dec- and long overdue, there is a risk that making major policy ades of authoritarian rule. In an address to the nation on 1 changes in a context of unreliable data and weak econom- March 2012 marking his first year in office, President Thein ic institutions could create unintended economic shocks. Sein made clear that the goal was to introduce “genuine Given the high levels of impoverishment and vulnerabil- democracy” and that there was still much more to be done. ity, even a relatively minor shock has the potential to have This ambitious agenda includes further democratic reform, a major impact on livelihoods. At a time when expectations healing bitter wounds of the past, rebuilding the economy are running high, and authoritarian controls on the popu- and ensuring the rule of law, as well as respecting ethnic lation have been loosened, there would be a potential for diversity and equality. The changes are real, but the chal- unrest. lenges are complex and numerous. To consolidate and build on what has been achieved and increase the likeli- A third challenge is consolidating peace in ethnic areas. -

Identity Crisis: Ethnicity and Conflict in Myanmar

Identity Crisis: Ethnicity and Conflict in Myanmar Asia Report N°312 | 28 August 2020 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 235 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. A Legacy of Division ......................................................................................................... 4 A. Who Lives in Myanmar? ............................................................................................ 4 B. Those Who Belong and Those Who Don’t ................................................................. 5 C. Contemporary Ramifications..................................................................................... 7 III. Liberalisation and Ethno-nationalism ............................................................................. 9 IV. The Militarisation of Ethnicity ......................................................................................... 13 A. The Rise and Fall of the Kaungkha Militia ................................................................ 14 B. The Shanni: A New Ethnic Armed Group ................................................................. 18 C. An Uncertain Fate for Upland People in Rakhine -

Burma - Conduct of Elections and the Release of Opposition Leader Aung San Suu Kyi

C 99 E/120 EN Official Journal of the European Union 3.4.2012 Thursday 25 November 2010 Burma - conduct of elections and the release of opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi P7_TA(2010)0450 European Parliament resolution of 25 November 2010 on Burma – conduct of elections and the release of opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi (2012/C 99 E/23) The European Parliament, — having regard to its previous resolutions on Burma, the most recent adopted on 20 May 2010 ( 1 ), — having regard to Articles 18- 21 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) of 1948, — having regard to Article 25 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) of 1966, — having regard to the EU Presidency Statement of 23 February 2010 calling for all-inclusive dialogue between the authorities and the democratic forces in Burma, — having regard to the statement of the President of the European Parliament Jerzy Buzek of 11 March 2010 on Burma’s new election laws, — having regard to the Chairman’s Statement at the 16th ASEAN Summit held in Hanoi on 9 April 2010, — having regard to the Council Conclusions on Burma adopted at the 3009th Foreign Affairs Council meeting in Luxembourg on 26 April 2010, — having regard to the European Council Conclusions, Declaration on Burma, of 19 June 2010, — having regard to the UN Secretary-General’s report on the situation of human rights in Burma of 28 August 2009, — having regard to the statement made by UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon in Bangkok on 26 October 2010, — having regard to the Chair’s statement at the -

Total Detention, Charge and Fatality Lists

ARRESTS No. Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark S: 8 of the Export and Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD Import Law and S: 25 leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and of the Natural Superintendent Kyi President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Disaster Management Lin of Special Branch, 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F General Aung San State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and law, Penal Code - Dekkhina District regions were also detained. 505(B), S: 67 of the Administrator Telecommunications Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD S: 25 of the Natural leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Disaster Management Superintendent President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s law, Penal Code - Myint Naing, 2 (U) Win Myint M U Tun Kyin President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and 505(B), S: 67 of the Dekkhina District regions were also detained. Telecommunications Administrator Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 3 (U) Henry Van Thio M Vice President 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Speaker of the Union Assembly, the President U Win Myint were detained. -

The Union Report the Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Census Report Volume 2

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report The Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Volume Report : Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population May 2015 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 For more information contact: Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population Office No. 48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431 062 www.dop.gov.mm May, 2015 Figure 1: Map of Myanmar by State, Region and District Census Report Volume 2 (Union) i Foreword The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census (2014 MPHC) was conducted from 29th March to 10th April 2014 on a de facto basis. The successful planning and implementation of the census activities, followed by the timely release of the provisional results in August 2014 and now the main results in May 2015, is a clear testimony of the Government’s resolve to publish all information collected from respondents in accordance with the Population and Housing Census Law No. 19 of 2013. It is my hope that the main census results will be interpreted correctly and will effectively inform the planning and decision-making processes in our quest for national development. The census structures put in place, including the Central Census Commission, Census Committees and Offices at all administrative levels and the International Technical Advisory Board (ITAB), a group of 15 experts from different countries and institutions involved in censuses and statistics internationally, provided the requisite administrative and technical inputs for the implementation of the census. -

Election Monitor No.49

Euro-Burma Office 10 November 22 November 2010 Election Monitor ELECTION MONITOR NO. 49 DIPLOMATS OF FOREIGN MISSIONS OBSERVE VOTING PROCESS IN VARIOUS STATES AND REGIONS Representatives of foreign embassies and UN agencies based in Myanmar, members of the Myanmar Foreign Correspondents Club and local journalists observed the polling stations and studied the casting of votes at a number of polling stations on the day of the elections. According the state-run media, the diplomats and guests were organized into small groups and conducted to the various regions and states to witness the elections. The following are the number of polling stations and number of eligible voters for the various regions and states:1 1. Kachin State - 866 polling stations for 824,968 eligible voters. 2. Magway Region- 4436 polling stations in 1705 wards and villages with 2,695,546 eligible voters 3. Chin State - 510 polling stations with 66827 eligible voters 4. Sagaing Region - 3,307 polling stations with 3,114,222 eligible voters in 125 constituencies 5. Bago Region - 1251 polling stations and 1057656 voters 6. Shan State (North ) - 1268 polling stations in five districts, 19 townships and 839 wards/ villages and there were 1,060,807 eligible voters. 7. Shan State(East) - 506 polling stations and 331,448 eligible voters 8. Shan State (South)- 908,030 eligible voters cast votes at 975 polling stations 9. Mandalay Region - 653 polling stations where more than 85,500 eligible voters 10. Rakhine State - 2824 polling stations and over 1769000 eligible voters in 17 townships in Rakhine State, 1267 polling stations and over 863000 eligible voters in Sittway District and 139 polling stations and over 146000 eligible voters in Sittway Township. -

December 2008

cover_asia_report_2008_2:cover_asia_report_2007_2.qxd 28/11/2008 17:18 Page 1 Central Committee for Drug Lao National Commission for Drug Office of the Narcotics Abuse Control Control and Supervision Control Board Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 500, A-1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: (+43 1) 26060-0, Fax: (+43 1) 26060-5866, www.unodc.org Opium Poppy Cultivation in South East Asia Lao PDR, Myanmar, Thailand OPIUM POPPY CULTIVATION IN SOUTH EAST ASIA IN SOUTH EAST CULTIVATION OPIUM POPPY December 2008 Printed in Slovakia UNODC's Illicit Crop Monitoring Programme (ICMP) promotes the development and maintenance of a global network of illicit crop monitoring systems in the context of the illicit crop elimination objective set by the United Nations General Assembly Special Session on Drugs. ICMP provides overall coordination as well as direct technical support and supervision to UNODC supported illicit crop surveys at the country level. The implementation of UNODC's Illicit Crop Monitoring Programme in South East Asia was made possible thanks to financial contributions from the Government of Japan and from the United States. UNODC Illicit Crop Monitoring Programme – Survey Reports and other ICMP publications can be downloaded from: http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/crop-monitoring/index.html The boundaries, names and designations used in all maps in this document do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. This document has not been formally edited. CONTENTS PART 1 REGIONAL OVERVIEW ..............................................................................................3 -

Frontier Capitalism and Politics of Dispossession in Myanmar: the Case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) Nickel Mine in Chin State Einzenberger, Rainer

www.ssoar.info Frontier Capitalism and Politics of Dispossession in Myanmar: the Case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) Nickel Mine in Chin State Einzenberger, Rainer Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Einzenberger, R. (2018). Frontier Capitalism and Politics of Dispossession in Myanmar: the Case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) Nickel Mine in Chin State. ASEAS - Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies, 11(1), 13-34. https:// doi.org/10.14764/10.ASEAS-2018.1-2 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/deed.de Aktuelle Südostasienforschung Current Research on Southeast Asia Frontier Capitalism and Politics of Dispossession in Myanmar: The Case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) Nickel Mine in Chin State Rainer Einzenberger ► Einzenberger, R. (2018). Frontier capitalism and politics of dispossession in Myanmar: The case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) nickel mine in Chin State. Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies, 11(1), 13-34. Since 2010, Myanmar has experienced unprecedented political and economic changes described in the literature as democratic transition or metamorphosis. The aim of this paper is to analyze the strategy of accumulation by dispossession in the frontier areas as a precondition and persistent element of Myanmar’s transition.