Volume XIV Number 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Managing the Human Weapon System: a Vision for an Air Force Human-Performance Doctrine

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive DSpace Repository Faculty and Researchers Faculty and Researchers Collection 2009 Managing the Human Weapon System: A Vision for an Air Force Human-Performance Doctrine Tvaryanas, A.P. Tvaryanas, A.P., Brown, L., and Miller, N.L. "Managing the Human Weapon System: A Vision for an Air Force Human-Performance Doctrine", Air & Space Power Journal, pp. 34-41, Summer 2009. http://hdl.handle.net/10945/36508 Downloaded from NPS Archive: Calhoun In air combat, “the merge” occurs when opposing aircraft meet and pass each other. Then they usually “mix it up.” In a similar spirit, Air and Space Power Journal’s “Merge” articles present contending ideas. Readers are free to join the intellectual battlespace. Please send comments to [email protected] or [email protected]. Managing the Human Weapon System A Vision for an Air Force Human-Performance Doctrine LT COL ANTHONY P. TVARYANAS, USAF, MC, SFS COL LEX BROWN, USAF, MC, SFS NITA L. MILLER, PHD* The basic planning, development, organization and training of the Air Force must be well rounded, covering every modern means of waging air war. The Air Force doctrines likewise must be !exible at all times and entirely uninhibited by tradition. —Gen Henry H. “Hap” Arnold N A RECENT paper on America’s Air special operations forces’ declaration that Force, Gen T. Michael Moseley asserted “humans are more important than hardware” that we are at a strategic crossroads as a in asymmetric warfare.2 Consistent with this consequence of global dynamics and view, in January 2004, the deputy secretary of Ishifts in the character of future warfare; he defense directed the Joint Staff to “develop also noted that “today’s con!uence of global the next generation of . -

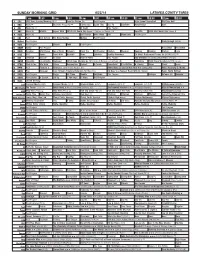

Sunday Morning Grid 6/22/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/22/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program High School Basketball PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Justin Time Tree Fu LazyTown Auto Racing Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Wildlife Exped. Wild 2014 FIFA World Cup Group H Belgium vs. Russia. (N) SportCtr 2014 FIFA World Cup: Group H 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Program Crazy Enough (2012) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Paid Program RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Wild Places Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Cooking Kitchen Lidia 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News LinkAsia Healthy Hormones Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour of Power Paid Program Into the Blue ›› (2005) Paul Walker. (PG-13) 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Backyard 2014 Copa Mundial de FIFA Grupo H Bélgica contra Rusia. (N) República 2014 Copa Mundial de FIFA: Grupo H 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Harvest In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio Austria. -

Perancangan Karakter Game Visual Novel “Tikta Kavya” Dengan Konsep Visual Bishonen

vi PERANCANGAN KARAKTER GAME VISUAL NOVEL “TIKTA KAVYA” DENGAN KONSEP VISUAL BISHONEN Nama Mahasiswa : Brigitta Rena Estidianti NRP : 3409100029 Jurusan : Desain Produk Industri FTSP-ITS Dosen Pembimbing : Rahmatsyam Lakoro, S.Sn, M.T ABSTRAK Industri game terus mengalami perkembangan, khususnya industri game di dalam negeri. Tetapi, di Indonesia fungsi game belum dimanfaatkan secara maksimal sebagai media komunikasi terutama dalam mengkomunikasikan sejarah dan budaya Indonesia kepada generasi muda. Hal tersebut dapat diatasi dengan menggunakan genre visual novel yang dinilai maksimal dalam menjalankan fungsi game sebagai media komunikasi. Walau begitu visual novel merupakan genre yang masih baru di Indonesia, karena itulah dipilih tema Majapahit sebagai kerajaan Indonesia yang sudah dikenal banyak orang. Sejarah kerajaan Majapahit dihiasi oleh para tokoh – tokoh besar seperti Raden Wijaya, Gajah Mada, sampai Hayam Wuruk. Personaliti dan karakteristik tokoh sentral majapahit tersebut memiliki potensi untuk menjadi karakter yang segar dan baru bila digabungkan dengan selera dan trend sekarang, tidak terjebak lagi pada stereotype komik silat. Di lain pihak visual novel memiliki potensi negatif yang membuat orang merasa bosan saat memainkannya, dilakukanlah pengoptimalan fitur simulatif pada elemen karakter. Fitur simulatif dapat digali lebih lanjut. Wujud akhir perancangan ini selain merancang sebuah game pada umumnya juga mengubah citra karakter desain tokoh sejarah Indonesia yang masih kental akan gaya gambar komik klasik dan kurang cocok -

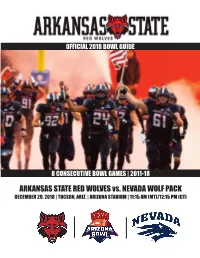

2018 A-STATE FB GAME NOTES Layout 1

OFFICIAL 2018 BOWL GUIDE 8 CONSECUTIVE BOWL GAMES | 2011-18 ARKANSAS STATE RED WOLVES vs. NEVADA WOLF PACK DECEMBER 29, 2018 | TUCSON, ARIZ. | ARIZONA STADIUM | 11:15 AM (MT)/12:15 PM (CT) 2018 ALL-SUN BELT CONFERENCE PLAYER OF THE YEAR DEFENSIVE PLAYER OF THE YEAR JUSTICE HANSEN, SR. QB RONHEEN BINGHAM, SR. DE NEWCOMER OF THE YEAR FRESHMAN OF THE YEAR KIRK MERRITT, JR. WR MARCEL MURRAY, FR. RB ARKANSAS STATE ATHLETICS MEDIA RELATIONS MAIN PHONE NUMBER: 870-972-2541 FAX: 870-972-3367 MAILING ADDRESS: P.O. Box 1000, State University, AR 72467 OVERNIGHT ADDRESS: 217 Olympic Dr., Jonesboro, AR 72401 Assoc. AD/Sports Information Dir.: Jerry Scott | [email protected] | 870-972-3405 (office) | 870-243-6021 (cell) 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015 & 2016 SUN BELT CONFERENCE CHAMPIONS ‘18 Arizona Bowl | ‘17 Camellia Bowl | ‘16 Cure Bowl | ‘05 & ‘15 New Orleans Bowl | 2012-15 GoDaddy Bowl ARIZONA BOWL: Arkansas State (8-4) vs. Nevada (7-5) December 29, 2018 | Arizona Stadium Tucson, Ariz. | 12:15 p.m. CT Radio: EAB Red Wolves Sports Network (107.9 FM, flagship) Television: CBS Sports Network ARKANSAS STATE QUICK FACTS Live Stats: AStateStats.com Location: Jonesboro, Ark. (74,489) | Enrollment: 13,930 Live Game Notes: twitter.com/AStateGameDay Nickname: Red Wolves | Colors: Scarlet and Black Stadium: Centennial Bank Stadium (30,382) | Playing Surface: ON TAP: Set to play its eighth consecutive bowl game, Arkansas State will face Nevada at Arizona Stadium on GEO Surfaces Field Turf | Conference: Sun Belt Saturday, Dec. 29, at 12:15 p.m. (CT) in the 2018 NOVA Home Loans Arizona Bowl. -

Swordplay Through the Ages Daniel David Harty Worcester Polytechnic Institute

Worcester Polytechnic Institute Digital WPI Interactive Qualifying Projects (All Years) Interactive Qualifying Projects April 2008 Swordplay Through The Ages Daniel David Harty Worcester Polytechnic Institute Drew Sansevero Worcester Polytechnic Institute Jordan H. Bentley Worcester Polytechnic Institute Timothy J. Mulhern Worcester Polytechnic Institute Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/iqp-all Repository Citation Harty, D. D., Sansevero, D., Bentley, J. H., & Mulhern, T. J. (2008). Swordplay Through The Ages. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/iqp-all/3117 This Unrestricted is brought to you for free and open access by the Interactive Qualifying Projects at Digital WPI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Interactive Qualifying Projects (All Years) by an authorized administrator of Digital WPI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IQP 48-JLS-0059 SWORDPLAY THROUGH THE AGES Interactive Qualifying Project Proposal Submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation by __ __________ ______ _ _________ Jordan Bentley Daniel Harty _____ ________ ____ ________ Timothy Mulhern Drew Sansevero Date: 5/2/2008 _______________________________ Professor Jeffrey L. Forgeng. Major Advisor Keywords: 1. Swordplay 2. Historical Documentary Video 3. Higgins Armory 1 Contents _______________________________ ........................................................................................0 Abstract: .....................................................................................................................................2 -

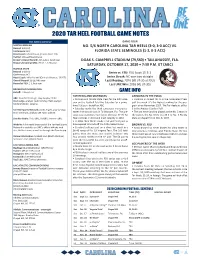

2020 Tar Heel Football Game Notes

2020 TAR HEEL FOOTBALL GAME NOTES THIS WEEK’S MATCHUP GAME FOUR NORTH CAROLINA NO. 5/6 NORTH CAROLINA TAR HEELS (3-0, 3-0 ACC) VS. Record: 3-0 (3-0) Conference: ACC FLORIDA STATE SEMINOLES (1-3, 0-3 ACC) Head Coach: Mack Brown (Florida State ‘74) Twitt er: @CoachMackBrown Brown’s Overall Record: 254-128-1, 32nd year DOAK S. CAMPBELL STADIUM (79,560) • TALLAHASSEE, FLA. Brown’s Record at UNC: 79-52-1, 12th year SATURDAY, OCTOBER 17, 2020 • 7:30 P.M. ET (ABC) FLORIDA STATE Record: 1-3 (0-3) Series vs. FSU: FSU leads 15-3-1 Conference: ACC Head Coach: Mike Norvell (Central Arkansas, '05 '07) Series Streak: NC won two straight Overall Record: 39-18, fi ft h year Last Meeti ng: 2016 (W, 37-35 at FSU) Record at FSU: 1-3, fi rst year Last UNC Win: 2016 (W, 37-35) BROADCAST INFORMATION Kickoff : 7:30 p.m. ET GAME INFO TAR HEELS AND SEMINOLES CAROLINA IN THE POLLS ABC: Sean McDonough, play-by-play; Todd • Carolina and Florida State meet for the 20th occa- • Carolina is ranked No. 5 in the Associated Press Blackledge, analyst; Todd McShay, fi eld analyst; sion on the football fi eld this Saturday for a prime- poll this week. It's the highest ranking for the pro- Molly McGrath, sideline ti me 7:30 p.m. kickoff on ABC. gram since November 1997. The Tar Heels sit at No. Tar Heel Sports Network: Jones Angell, play-by-play; • Saturday marks the third successive meeti ng be- 6 in the Amway Coaches Poll. -

Adrian Maher

ADRIAN MAHER WRITER/DIRECTOR/SUPERVISING PRODUCER Los Angeles, CA Cell: (310) 922-3080 Email: [email protected] Website: www.maherproductions.com ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE – REALITY AND DOCUMENTARY TELEVISION More than two decades of experience as a writer/director of documentary television programs, print journalist, on-air reporter, book author and private investigator. Strong writing, directing, producing, voiceover, investigative, digital media, and managerial skills. UNSUNG HOLLYWOOD: HARLEM GLOBETROTTERS: (TV ONE NETWORK) (ASmith and Company) Wrote, Directed and Produced a one -hour episode on the history of the Harlem Globetrotters from their founding in Chicago in 1927 to their present-day status as one of the most recognizable sports brands in the world. SPLIT-SECOND DECISION: (MSNBC) (The Gurin Company) Wrote, Directed and Produced three one-hour documentaries about people caught in catastrophic situations and the instant decisions they make to survive. UNSUNG HOLLYWOOD: RICHARD ROUNDTREE: (TV ONE NETWORK) (ASmith and Company) Wrote, and Produced a one-hour episode/biography on America’s first black-action movie star – Richard Roundtree – (star of “Shaft”) and the “blaxploitation” era in Hollywood films. TRIGGERS: WEAPONS THAT CHANGED THE WORLD (MILITARY CHANNEL) (Morningstar Entertainment) Wrote and Produced several episodes on history’s most fearsome weapons including “Gatling Guns,” “Tanks” and “Light Machine Guns.” -

SFU Thesis Template Files

“To Fight the Battles We Never Could”: The Militarization of Marvel’s Cinematic Superheroes by Brett Pardy B.A., The University of the Fraser Valley, 2013 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Communication Faculty of Communication, Art, and Technology Brett Pardy 2016 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2016 Approval Name: Brett Pardy Degree: Master of Arts Title: “To Fight the Battles We Never Could”: The Militarization of Marvel’s Cinematic Superheroes Examining Committee: Chair: Frederik Lesage Assistant Professor Zoë Druick Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Adel Iskander Supervisor Assistant Professor Michael Ma External Examiner Faculty Member Department of Criminology Kwantlen Polytechnic University Date Defended/Approved: June 16, 2016 ii Abstract The Marvel comics film adaptations have been some of the most successful Hollywood products of the post 9/11 period, bringing formerly obscure cultural texts into the mainstream. Through an analysis of the adaptation process of Marvel Entertainment’s superhero franchise from comics to film, I argue that a hegemonic American model of militarization has been used by Hollywood as a discursive formation with which to transform niche properties into mass market products. I consider the locations of narrative ambiguities in two key comics texts, The Ultimates (2002-2007) and The New Avengers (2005-2012), as well as in the film The Avengers (2012), and demonstrate the significant reorientation of the film franchise towards the American military’s “War on Terror”. While Marvel had attempted to produce film adaptations for decades, only under the new “militainment” discursive formation was it finally successful. -

State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations for Fiscal Year 2018

STATE, FOREIGN OPERATIONS, AND RELATED PROGRAMS APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2018 TUESDAY, MAY 9, 2017 U.S. SENATE, SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS, Washington, DC. The subcommittee met at 2:30 p.m., in room SD–192, Dirksen Senate Office Building, Hon. Lindsey Graham (chairman) pre- siding. Present: Senators Graham, Moran, Boozman, Daines, Leahy, Durbin, Shaheen, Coons, Murphy and Van Hollen. UNITED STATES DEMOCRACY ASSISTANCE STATEMENTS OF: HON. MADELEINE ALBRIGHT, CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD, THE NA- TIONAL DEMOCRATIC INSTITUTE HON. STEPHEN HADLEY, CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD, THE UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE HON. VIN WEBER, CO-VICE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD, THE NA- TIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR DEMOCRACY HON. JAMES KOLBE, VICE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD, THE INTER- NATIONAL REPUBLICAN INSTITUTE TESTIMONY FROM DEMOCRACY PROGRAM BENEFICIARIES OUTSIDE WITNESS TESTIMONY SUBMITTED SUBSEQUENT TO THE HEARING OPENING STATEMENT OF SENATOR LINDSEY GRAHAM Senator GRAHAM. Thank you all. The subcommittee will come to order. Today, our hearing is on United States Democracy Assist- ance. I would like to welcome our witnesses who deserve long, glowing introductions—but you’re not going to get one because we got to get on one with the hearing. We’ve got Madeleine Albright, Chairman of the Board of the Na- tional Democratic Institute and former Secretary of State. Wel- come, Ms. Albright. James Kolbe, Vice-Chairman of the Board of the International Republican Institute. Jim, welcome. Vin Weber, Co-Vice Chairman of the Board of the National En- dowment for Democracy, all around good guy, Republican type. Stephen Hadley, Chairman of the Board of the United States In- stitute of Peace. -

2012 Program Guide

table of contents 3 Letter from the Con Chair 4 Guests of Honor 14 Events 23 Video Programming 26 Panels & Workshops 33 Artists’ Alley 39 Dealers’ Room 41 Room Directory 43 Maps 50 Where to Eat 60 Getting Around 61 Rules 67 Sponsors 68 Volunteering 69 Staff 72 Autographs APRIL 6–8, 2012 1 ANIME BOSTON CELEBRATES 10 YEARS! 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 Attendance: Attendance: Attendance: Attendance: Attendance: 4,110 3,656 7,500 9,354 11,500 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 Attendance: Attendance: Attendance: Attendance: Attendance: 14,339 15,438 17,236 19,136 ????? This weekend we're celebrating Anime Boston's 10th anniversary. We would never have reached this milestone year without our fabulous guests, the support and effort of our staff, and the overwhelming love and inspiration our attendees have provided over the last nine years. Thank you! 2 Anime Boston 2012 LETTER FROM THE CON CHAIR Greetings! On behalf of the New England Anime Society, our honored guests and the entire Anime Boston staff, it is my honor and pleasure to welcome you to Anime Boston 2012! This year is particularly exciting, as we are celebrating our tenth anniversary. When I think back on 2002, when we were working to organize ourselves and plan for the first year of the convention, I’m still astounded at how much has the event has grown and developed. Like a child, the convention “grew up” faster than we expected, and around it, we have lived ten years of life. For those of us who were there from the beginning this means ten years of marriages, children born, friends who have passed on, break-ups, falling in love, learning new things, losing some battles, and winning others. -

2020 Tar Heel Football Game Notes

2020 TAR HEEL FOOTBALL GAME NOTES THIS WEEK’S MATCHUP GAME NINE NORTH CAROLINA #25/#23 NORTH CAROLINA TAR HEELS (6-2, 6-2 ACC) VS. Record: 6-2 (6-2) Conference: ACC #2/#2 NOTRE DAME FIGHTING IRISH (8-0, 7-0 ACC) Head Coach: Mack Brown (Florida State ‘74) Twitt er: @CoachMackBrown Brown’s Overall Record: 257-130-1, 32nd year KENAN STADIUM (50,500/3,535) • CHAPEL HILL, N.C. Brown’s Record at UNC: 82-54-1, 12th year FRIDAY, NOV. 27, 2020 • 3:30 P.M. ET (ABC) NOTRE DAME Record: 8-0 (7-0) Series vs. ND: ND leads 18-2 Conference: ACC Head Coach: Brian Kelly Series Streak: ND won last two Overall Record: 271-94-2, 30th year Last Meeti ng at UNC: 2017 (L, 33-10) Record at ND: 100-37, 11th year Last UNC Win: 2008 (W, 29-24) BROADCAST INFORMATION Kickoff : 3:30 p.m. ET GAME INFO TAR HEELS AND FIGHTING IRISH LAST TIME OUT ABC: Chris Fowler, play-by-play; Kirk Herbstreit, • North Carolina and Notre Dame meet for the 21st • Sam Howell set school records for passing yards analyst; Maria Taylor, sideline ti me in a series that began in 1949. (550), total touchdowns (7) and passing touchdowns Tar Heel Sports Network: Jones Angell, play-by-play; • Notre Dame leads the series 18-2-0. Both Caro- (6) in leading Carolina to a 59-53 victory over Wake Lee Pace, analyst lina victories occurred in Chapel Hill. The Tar Heels Forest on Saturday, Nov. 14. scored a 12-7 decision in 1960 and beat the Fighti ng • Notre Dame extended the nati on’s longest winning Satellite Radio: Sirius (84), XM (84), Internet (84) Irish, 29-24, in 2008. -

La Animación Y Las Otras Artes Actas Del III Foro Académico Internacional Sobre Animación VII Festival Internacional De Animación De Córdoba ANIMA2013

La Animación y las otras Artes Actas del III Foro Académico Internacional Sobre Animación VII Festival Internacional de Animación de Córdoba ANIMA2013 Centro Experimental de Animación Dpto. de Cine y Televisión Facultad de Artes Universidad Nacional de Córdoba La animación y las otras artes: actas del III Foro Académico Internacional Sobre Animación / Alejandro Rodrigo González ... [et.al.] ; compilado por Paula Andrea Asís Ferri y Alejandro Rodrigo González. - 1a ed. - Córdoba: Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, 2014. E-Book. ISBN 978-950-33-1096-0 1. Animación. 2. Arte. 3. Audiovisuales. I. González, Alejandro Rodrigo II. Asís Ferri, Paula Andrea, comp. III. González, Alejandro Rodrigo, comp. CDD 791.43 Fecha de catalogación: 05/12/2013 Autoridades Universidad nacional de Córdoba Rector: Dr. Francisco Tamarit Vicerectora: Dra. Silvia Barei Facultad de Artes Decana: Lic. Ana Guillermina Yukelson Vicedecano: Prof. Dardo Alzogaray Departamento de Cine y Tv: Director disciplinar: Mgter. Ana Mohaded Centro Experimental de Animación: Coordinadora General: Esp. Carmen Garzón Coordinador Área Producción, Gestión y Extensión : Esp. Alejandro R. González Coordinadora del Área Docencia e Investigación en Animación: Esp. Paula A. Asís ferri Autoridades Universidad nacional de Villa maría Rector: Ab. Martín Gill Vicerectora: Dra. Cecilia Conci IAPCH Decano: Ab. Luis Negretti Autoridades Centro Cultural España Córdoba Directora: Daniela Bobbio 2 LA ANIMACIÓN Y LAS OTRAS ARTES ACTAS DEL III FORO ACADÉMICO INTERNACIONAL SOBRE ANIMACIÓN - ANIMA2013 -