“The Land of the Fine Triremes:” Naval Identity and Polis Imaginary in 5Th

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Homeric Time Travel Erwin F

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Classical Studies Faculty Research Classical Studies Department 7-2018 Homeric Time Travel Erwin F. Cook Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/class_faculty Part of the Classics Commons Repository Citation Cook, E.F. (2018). Homeric time travel. Literary Imagination, 20(2), 220-221. doi:10.1093/litimag/imy065 This Post-Print is brought to you for free and open access by the Classical Studies Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Classical Studies Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Homeric Time Travel In a recent pair of articles I argued that the Odyssey presents itself as the heroic analogue to, or even substitute for, fertility myth.1 The return of Odysseus thus heralds the return of prosperity to his kingdom in a manner functionally equivalent to the return of Persephone, and with her of life, to earth in springtime. The first paper focused on a detailed comparison of the plots of the Homeric Hymn to Demeter and the Odyssey;2 and the second on the relationship between Persephone’s withdrawal and return and the narrative device of ring-composition.3 In my analysis of ring-composition, I concluded that what began as a cognitive and functional pattern, organizing small-scale narrative structures, evolved into an aesthetic pattern, organizing large blocks of narrative, before finally becoming an ideological pattern, connecting the hero’s return to the promise of renewal offered by fertility myth and cult. -

Piraeus Case Report Consolidated 30062015

Piraeus Case Report Evi Georgaki, N. Hlepas University of Athens Municipality of Piraeus Evi Georgaki, N. Hlepas Contents Abstract..........................................................................................................................6 Introduction....................................................................................................................6 Types of sources - The empirical corpus of the Piraeus case.....................................6 Socioeconomic features of the Municipal of Piraeus ....................................................7 General Information ...................................................................................................7 Municipal History ....................................................................................................10 Economic features....................................................................................................12 The Municipality of Piraeus: Political leadership and the fiscal problem...................15 Party political landscape and the political leadership of the municipality 2006-2014 ..................................................................................................................................15 Local Elections: 15 and 22 October 2006 ............................................................15 th Parliamentary Elections, 16 of September 2007 ................................................16 th Parliamentary Elections, 4 of October 2009.......................................................16 -

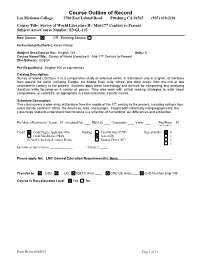

Course Outline of Record Los Medanos College 2700 East Leland Road Pittsburg CA 94565 (925) 439-2181

Course Outline of Record Los Medanos College 2700 East Leland Road Pittsburg CA 94565 (925) 439-2181 Course Title: Survey of World Literature II: Mid-17th Century to Present Subject Area/Course Number: ENGL-145 New Course OR Existing Course Instructor(s)/Author(s): Karen Nakaji Subject Area/Course No.: English 145 Units: 3 Course Name/Title: Survey of World Literature II: Mid-17th Century to Present Discipline(s): English Pre-Requisite(s): English 100 or equivalency Catalog Description: Survey of World Literature II is a comparative study of selected works, in translation and in English, of literature from around the world, including Europe, the Middle East, Asia, Africa, and other areas, from the mid or late seventeenth century to the present. Students apply basic terminology and devices for interpreting and analyzing literature while focusing on a variety of genres. They also work with critical reading strategies to write about comparisons, or contrasts, as appropriate in a baccalaureate, transfer course. Schedule Description: This class covers a wide array of literature from the middle of the 17th century to the present, including authors from every literate continent: Africa, the Americas, Asia, and Europe. Taught both historically and geographically, the class helps students understand how literature is a reflection of humankind, our differences and similarities. Hrs/Mode of Instruction: Lecture: 54 Scheduled Lab: ____ HBA Lab: ____ Composition: ____ Activity: ____ Total Hours 54 (Total for course) Credit Credit Degree Applicable -

London and Middlesex in the 1660S Introduction: the Early Modern

London and Middlesex in the 1660s Introduction: The early modern metropolis first comes into sharp visual focus in the middle of the seventeenth century, for a number of reasons. Most obviously this is the period when Wenceslas Hollar was depicting the capital and its inhabitants, with views of Covent Garden, the Royal Exchange, London women, his great panoramic view from Milbank to Greenwich, and his vignettes of palaces and country-houses in the environs. His oblique birds-eye map- view of Drury Lane and Covent Garden around 1660 offers an extraordinary level of detail of the streetscape and architectural texture of the area, from great mansions to modest cottages, while the map of the burnt city he issued shortly after the Fire of 1666 preserves a record of the medieval street-plan, dotted with churches and public buildings, as well as giving a glimpse of the unburned areas.1 Although the Fire destroyed most of the historic core of London, the need to rebuild the burnt city generated numerous surveys, plans, and written accounts of individual properties, and stimulated the production of a new and large-scale map of the city in 1676.2 Late-seventeenth-century maps of London included more of the spreading suburbs, east and west, while outer Middlesex was covered in rather less detail by county maps such as that of 1667, published by Richard Blome [Fig. 5]. In addition to the visual representations of mid-seventeenth-century London, a wider range of documentary sources for the city and its people becomes available to the historian. -

CLIL Multikey Lesson Plan LESSON PLAN

CLIL MultiKey lesson plan LESSON PLAN Subject: Art History Topic: The Athenian acropolis Students' age: 14-15 Language level: B1 Time: 2 hours Content aims: Art History (and a bit of History) on ancient Greece and the poleis. To describe an artistic element of an ancient city To understand the political role of Art and Religion in Ancient Greece Language aims: - Listening activity - Learn and use new vocabulary - Knowledge of technical art and history vocabulary Pre-requisites: - Geographical and cartographical skill - Knowledge of Greek history from the Persian wars to Pericles; - The role of the city in the world Materials: - Personal computer - handouts Procedure steps: Teacher starts explaining the geographical asset: where is Greece in Europe, where is Athens, arriving to the map that shows the metropolis in the details. Then after a short brainstorming activity about the poleis, (birth and main characters) arrives to the substantial continuity of the word polis in English. Which are the words deriving from polis? acropolis, necropolis, metropolis, metropolitan; megalopolis, cosmopolitan; Politics Policy Police T. shows map and asks: 1 CLIL MultiKey lesson plan Where are the acropolis and the necropolis of Athens? Then t. shows a video, inviting students to understanding the following items: - Which was the Athenian political role? - Which politicians are quoted? Why? When do they live? - Which are the most relevant urban changes for Athens? Finally teacher invites students to complete the handout 2 CLIL MultiKey lesson plan HANDOUT a) Sites references: Image coins: http://www.ancientresource.com/lots/greek/coins_athens.html http://blogs-images.forbes.com/stephenpope/files/2011/05/300px-1_euro_coin_Gr_serie_1.png Athena's birth: http://galeri7.uludagsozluk.com/282/zeus_454246.png b) vvideos's transcripts 1) https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ancient-art-civilizations/greek-art/classical/v/parthenon Transcript Voiceover: We're looking at the Parthenon. -

Jocks, Ianto Thorvald (2020) Scribonius Largus' Compounding of Drugs (Compositiones Medicamentorum): Introduction, Translation, and Medico- Historical Comments

Jocks, Ianto Thorvald (2020) Scribonius Largus' Compounding of Drugs (Compositiones medicamentorum): introduction, translation, and medico- historical comments. PhD thesis. Vol. I: Introduction, medicine and pharmacy in contemporary context; reception http://theses.gla.ac.uk/82178/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Scribonius Largus' Compounding of Drugs (Compositiones medicamentorum) Introduction, Translation, and Medico-Historical Comments Vol I: Introduction, Medicine and Pharmacy in Contemporary Context, Reception Vol II: Translation with Explanatory and Medico-Historical Comments Ianto Thorvald Jocks Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classics) School of Humanities, Subject Area Classics College of Arts University of Glasgow June 2020 © Ianto Thorvald Jocks, 2020 ii Abstract Scribonius Largus’ Compounding of Drugs or Recipes for Remedies (Compositiones medicamentorum) is an important -

A „Szőke Tisza” Megmentésének Lehetőségei

A „SZŐKE TISZA” MEGMENTÉSÉNEK LEHETŐSÉGEI Tájékoztató Szentistványi Istvánnak, a szegedi Városkép- és Környezetvédelmi Bizottság elnökének Összeállította: Dr. Balogh Tamás © 2012.03.27. TIT – Hajózástörténeti, -Modellező és Hagyományőrző Egyesület 2 TÁJÉKOZTATÓ Szentistványi István, a szegedi Városkép- és Környezetvédelmi Bizottság elnöke részére a SZŐKE TISZA II. termesgőzössel kapcsolatban 2012. március 27-én Szentistványi István a szegedi Városkép- és Környezetvédelmi Bizottság elnöke e-mailben kért tájékoztatást Dr. Balogh Tamástól a TIT – Hajózástörténeti, -Modellező és Hagyományőrző Egyesület elnökétől a SZŐKE TISZA II. termesgőzössel kapcsolatban, hogy tájékozódjon a hajó megmentésének lehetőségéről – „akár jelentősebb anyagi ráfordítással, esetleges városi összefogással is”. A megkeresésre az alábbi tájékoztatást adom: A hajó 2012. február 26-án süllyedt el. Azt követően egyesületünk honlapján – egy a hajónak szentelt tematikus aloldalon – rendszeresen tettük közzé a hajóra és a mentésére vonatkozó információkat, képeket, videókat (http://hajosnep.hu/#!/lapok/lap/szoke-tisza-karmentes), amelyekből szinte napi ütemezésben nyomon követhetők a február 26-március 18 között történt események. A honlapon elérhető információkat nem kívánom itt megismételni. Egyebekben a hajó jelentőségéről és az esetleges városi véleménynyilvánítás elősegítésére az alábbiakat tartom szükségesnek kiemelni: I) A hajó jelentősége: Bár a Kulturális Örökségvédelmi Hivatal előtt jelenleg zajlik a hajó örökségi védelembe vételére irányuló eljárás (a hajó örökségi -

Reading the Remains of the 17Th Century

AnthroNotes Volume 28 No. 1 Spring 2007 WRITTEN IN BONE READING THE REMAINS OF THE 17TH CENTURY by Kari Bruwelheide and Douglas Owsley ˜ ˜ ˜ [Editor’s Note: The Smithsonian’s Department of Anthro- who came to America, many willingly and others under pology has had a long history of involvement in forensic duress, whose anonymous lives helped shaped the course anthropology by assisting law enforcement agencies in the of our country. retrieval, evaluation, and analysis of human remains for As we commemorate the 400th anniversary of the identification purposes. This article describes how settlement of Jamestown, it is clear that historians and ar- Smithsonian physical anthropologists are applying this same chaeologists have made much progress in piecing together forensic analysis to historic cases, in particular seventeenth the literary records and artifactual evidence that remain from century remains found in Maryland and Virginia, which the early colonial period. Over the past two decades, his- will be the focus of an upcoming exhibition, Written in Bone: torical archaeology especially has had tremendous success Forensic Files of the 17th Century, scheduled to open at the in charting the development of early colonial settlements Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in No- through careful excavations that have recovered a wealth vember 2008. This exhibition will cover the basics of hu- of 17th century artifacts, materials once discarded or lost, man anatomy and forensic investigation, extending these and until recently buried beneath the soil (Kelso 2006). Such techniques to the remains of colonists teetering on the edge discoveries are informing us about daily life, activities, trade of survival at Jamestown, Virginia, and to the wealthy and relations here and abroad, architectural and defensive strat- well-established individuals of St. -

Leto As Mother: Representations of Leto with Apollo and Artemis in Attic Vase Painting of the Fifth Century B.C

https://publications.dainst.org iDAI.publications ELEKTRONISCHE PUBLIKATIONEN DES DEUTSCHEN ARCHÄOLOGISCHEN INSTITUTS Dies ist ein digitaler Sonderdruck des Beitrags / This is a digital offprint of the article Lavinia Foukara Leto as Mother: Representations of Leto with Apollo and Artemis in Attic Vase Painting of the Fifth Century B.C. aus / from Archäologischer Anzeiger Ausgabe / Issue Seite / Page 63–83 https://publications.dainst.org/journals/aa/2027/6626 • urn:nbn:de:0048-journals.aa-2017-1-p63-83-v6626.5 Verantwortliche Redaktion / Publishing editor Redaktion der Zentrale | Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Weitere Informationen unter / For further information see https://publications.dainst.org/journals/aa ISSN der Online-Ausgabe / ISSN of the online edition 2510-4713 ISSN der gedruckten Ausgabe / ISSN of the printed edition Verlag / Publisher Ernst Wasmuth Verlag GmbH & Co. Tübingen ©2019 Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Zentrale, Podbielskiallee 69–71, 14195 Berlin, Tel: +49 30 187711-0 Email: [email protected] / Web: dainst.org Nutzungsbedingungen: Mit dem Herunterladen erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen (https://publications.dainst.org/terms-of-use) von iDAI.publications an. Die Nutzung der Inhalte ist ausschließlich privaten Nutzerinnen / Nutzern für den eigenen wissenschaftlichen und sonstigen privaten Gebrauch gestattet. Sämtliche Texte, Bilder und sonstige Inhalte in diesem Dokument unterliegen dem Schutz des Urheberrechts gemäß dem Urheberrechtsgesetz der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Die Inhalte können von Ihnen nur dann genutzt und vervielfältigt werden, wenn Ihnen dies im Einzelfall durch den Rechteinhaber oder die Schrankenregelungen des Urheberrechts gestattet ist. Jede Art der Nutzung zu gewerblichen Zwecken ist untersagt. Zu den Möglichkeiten einer Lizensierung von Nutzungsrechten wenden Sie sich bitte direkt an die verantwortlichen Herausgeberinnen/Herausgeber der entsprechenden Publikationsorgane oder an die Online-Redaktion des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts ([email protected]). -

Applying Modern Immunology to the Plague of Ancient Athens

Pursuit - The Journal of Undergraduate Research at The University of Tennessee Volume 10 Issue 1 Article 7 May 2020 Applying Modern Immunology to the Plague of Ancient Athens Juhi C. Patel University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/pursuit Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Disease Modeling Commons, and the Epidemiology Commons Recommended Citation Patel, Juhi C. (2020) "Applying Modern Immunology to the Plague of Ancient Athens," Pursuit - The Journal of Undergraduate Research at The University of Tennessee: Vol. 10 : Iss. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/pursuit/vol10/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Volunteer, Open Access, Library Journals (VOL Journals), published in partnership with The University of Tennessee (UT) University Libraries. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Pursuit - The Journal of Undergraduate Research at The University of Tennessee by an authorized editor. For more information, please visit https://trace.tennessee.edu/pursuit. Applying Modern Immunology to the Plague of Ancient Athens Cover Page Footnote The author would like to thank Dr. Aleydis Van de Moortel at the University of Tennessee for research supervision and advice. This article is available in Pursuit - The Journal of Undergraduate Research at The University of Tennessee: https://trace.tennessee.edu/pursuit/vol10/iss1/7 1.1 Introduction. After the Persian wars in the early fifth century BC, Athens and Sparta had become two of the most powerful city-states in Greece. At first, they were allies against the common threat of the Persians. -

Athens Guide

ATHENS GUIDE Made by Dorling Kindersley 27. May 2010 PERSONAL GUIDES POWERED BY traveldk.com 1 Top 10 Athens guide Top 10 Acropolis The temples on the “Sacred Rock” of Athens are considered the most important monuments in the Western world, for they have exerted more influence on our architecture than anything since. The great marble masterpieces were constructed during the late 5th-century BC reign of Perikles, the Golden Age of Athens. Most were temples built to honour Athena, the city’s patron goddess. Still breathtaking for their proportion and scale, both human and majestic, the temples were adorned with magnificent, dramatic sculptures of the gods. Herodes Atticus Theatre Top 10 Sights 9 A much later addition, built in 161 by its namesake. Acropolis Rock In summer it hosts the Athens Festival (see Festivals 1 As the highest part of the city, the rock is an ideal and Events). place for refuge, religion and royalty. The Acropolis Rock has been used continuously for these purposes since Dionysus Theatre Neolithic times. 10 This mosaic-tiled theatre was the site of Classical Greece’s drama competitions, where the tragedies and Propylaia comedies by the great playwrights (Aeschylus, 2 At the top of the rock, you are greeted by the Sophocles, Euripides) were first performed. The theatre Propylaia, the grand entrance through which all visitors seated 15,000, and you can still see engraved front-row passed to reach the summit temples. marble seats, reserved for priests of Dionysus. Temple of Athena Nike (“Victory”) 3 There has been a temple to a goddess of victory at New Acropolis Museum this location since prehistoric times, as it protects and stands over the part of the rock most vulnerable to The Glass Floor enemy attack. -

Arrian's Voyage Round the Euxine

— T.('vn.l,r fuipf ARRIAN'S VOYAGE ROUND THE EUXINE SEA TRANSLATED $ AND ACCOMPANIED WITH A GEOGRAPHICAL DISSERTATION, AND MAPS. TO WHICH ARE ADDED THREE DISCOURSES, Euxine Sea. I. On the Trade to the Eqft Indies by means of the failed II. On the Di/lance which the Ships ofAntiquity ufually in twenty-four Hours. TIL On the Meafure of the Olympic Stadium. OXFORD: DAVIES SOLD BY J. COOKE; AND BY MESSRS. CADELL AND r STRAND, LONDON. 1805. S.. Collingwood, Printer, Oxford, TO THE EMPEROR CAESAR ADRIAN AUGUSTUS, ARRIAN WISHETH HEALTH AND PROSPERITY. We came in the courfe of our voyage to Trapezus, a Greek city in a maritime fituation, a colony from Sinope, as we are in- formed by Xenophon, the celebrated Hiftorian. We furveyed the Euxine fea with the greater pleafure, as we viewed it from the lame fpot, whence both Xenophon and Yourfelf had formerly ob- ferved it. Two altars of rough Hone are ftill landing there ; but, from the coarfenefs of the materials, the letters infcribed upon them are indiftincliy engraven, and the Infcription itfelf is incor- rectly written, as is common among barbarous people. I deter- mined therefore to erect altars of marble, and to engrave the In- fcription in well marked and diftinct characters. Your Statue, which Hands there, has merit in the idea of the figure, and of the defign, as it reprefents You pointing towards the fea; but it bears no refemblance to the Original, and the execution is in other re- fpects but indifferent. Send therefore a Statue worthy to be called Yours, and of a fimilar delign to the one which is there at prefent, b as 2 ARYAN'S PERIPLUS as the fituation is well calculated for perpetuating, by thefe means, the memory of any illuftrious perfon.