Mediations 29.1.Indb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LE MONDE/PAGES<UNE>

www.lemonde.fr 58 ANNÉE – Nº 17830 – 1,20 ¤ – FRANCE MÉTROPOLITAINE --- VENDREDI 24 MAI 2002 FONDATEUR : HUBERT BEUVE-MÉRY – DIRECTEUR : JEAN-MARIE COLOMBANI 0123 A Moscou, DES LIVRES L’école de Luc Ferry Bush et Poutine Roberto Calasso Grecs à Montpellier Illettrisme, enseignement professionnel, autorité : les trois priorités du ministre de l’éducation consacrent un Le cinéma et l’écrit LE NOUVEAU ministre de l’édu- f rapprochement cation nationale, Luc Ferry, expose Un entretien avec INCENDIE dans un entretien au Monde ses le nouveau ministre « historique » trois priorités : la lutte contre l’illet- de la jeunesse L’ambassade d’Israël trisme, la valorisation de l’enseigne- ment professionnel et la consolida- et de l’éducation LORS de sa première visite officiel- à Paris détruite dans la tion de l’autorité des professeurs, le en Russie, le président américain nuit. Selon la police, le qu’il lie à la sécurité. Pour l’illettris- George W. Bush signera avec Vladi- me, Luc Ferry reproche à ses prédé- f « Il faut revaloriser mir Poutine, vendredi 24 mai au feu était accidentel p. 11 cesseurs de n’avoir « rien fait Kremlin, un traité de désarmement depuis dix ans ». Il insiste sur le res- la pédagogie nucléaire qualifié d’« historique » et MAFIA pect des horaires de lecture et du travail » à l’école visant à « mettre fin à la guerre froi- d’écriture, ainsi que sur la prise en de ». Les deux pays s’engagent à Dix ans après la mort charge des jeunes en difficulté. réduire leurs arsenaux stratégiques à L’enseignement professionnel doit f Médecins : un niveau maximal de 2 200 ogives à du juge Falcone p. -

Tales of Adversity and Triumph in Collection

c/o Katina Strauch 209 Richardson Avenue MSC 98, The Citadel Charleston, SC 29409 REFERENCE PUBLISHING ISSUE TM volume 28, NUMBER 4 SEPTEMBER 2016 ISSN: 1043-2094 “Linking Publishers, Vendors and Librarians” Emerging from the Dark(room): Tales of Adversity and Triumph in Collection Development by Lindsey Reno (Acquisitions Librarian, Liaison to Fine Arts, Film Theatre, and Music, University of New Orleans, Early K. Long Library) <[email protected]> ollection development can be one of the in the face of adversity. My inspiration for ship in the library. Her article, “Censorship most contentious areas of a library. Ev- this issue came from my own experiences at- in the Library: The Dark Side of Dystopia” Ceryone in the library, as well as patrons tempting to start a leisure reading collection in provides us with the perspectives of both parent and other stakeholders, has an opinion about my library at the University of New Orleans. and librarian. Her recommendations on how to what a particular library should hold. Librari- It took three years of struggle, and countless approach challenges to literature are valuable ans and patrons alike can be fiercely protective meetings, to gain approval. Another story indeed. Everyone wants to read literature that of library collections. Throw in related issues, that inspired me to put together this issue was they can identify with and finding books with like budget cuts and space, and things can get that of LOUIS Consortium colleague Megan characters who mirror ourselves is important. awfully messy. The resulting Lowe, from the University of Unfortunately, the challenge of finding multi- conflicts are many and various. -

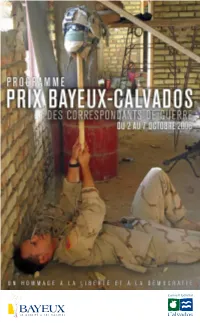

Programme-2006.Pdf

Programme PRIX BAYEUX-CALVADOS Édition 2006 DES CORRESPONDANTS DE GUERRE 2006 Lundi 2 octobre P Prix des lycéens J’ai le plaisir de vous Basse-Normandie présenter la 13e édition Mardi 3 octobre du Prix Bayeux-Calvados P Cinéma pour les collégiens des Correspondants de Guerre. Mercredi 4 octobre P Ouverture des expositions Fenêtre ouverte sur le monde, sur ses conflits, sur les difficultés du métier d’informer, Jeudi 5 octobre ce rendez-vous majeur des médias internationaux et du public rappelle, d’année en année, notre attachement à la démocratie et à son expression essentielle : P Soirée grands reporters : la liberté de la presse. Liban, nouveau carrefour Les débats, les projections et les expositions proposés tout au long de cette semaine de tous les dangers offrent au public et notamment aux jeunes l’éclairage de grands reporters et le décryptage d’une actualité internationale complexe et souvent dramatique. Vendredi 6 octobre Cette année plus que jamais, Bayeux témoignera de son engagement en inaugurant P Réunion du jury avec Reporters sans frontières, le « Mémorial des Reporters », site unique en Europe, international dédié aux journalistes du monde entier disparus dans l’exercice de leur profession pour nous délivrer une information libre, intègre et sincère. P Soirée hommage et projection en avant-première J’invite chacune et chacun d’entre vous à venir nous rejoindre du 2 au 7 octobre du film “ L’Étoile du Soldat ” à Bayeux, pour partager cette formidable semaine d’information, d’échange, d’hommage et d’émotion. de Christophe De Ponfilly PATRICK GOMONT Samedi 7 octobre Maire de Bayeux P Réunion du jury international et du jury public P Inauguration du Mémorial des reporters avec Reporters sans frontières P Salon du livre VOUS Le Prix du public, catégorie photo, aura lieu le samedi 7 octobre, de 10 h à 11 h, à la Halle aux Grains P SOUHAITEZ Table ronde sur la sécurité de Bayeux. -

The Future of Lebanon Hearing Committee On

S. HRG. 106–770 THE FUTURE OF LEBANON HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON NEAR EASTERN AND SOUTH ASIAN AFFAIRS OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED SIXTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JUNE 14, 2000 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Relations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/senate U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 67–981 CC WASHINGTON : 2000 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 15:20 Dec 05, 2000 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 67981 SFRELA1 PsN: SFRELA1 COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS JESSE HELMS, North Carolina, Chairman RICHARD G. LUGAR, Indiana JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Delaware CHUCK HAGEL, Nebraska PAUL S. SARBANES, Maryland GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut ROD GRAMS, Minnesota JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin CRAIG THOMAS, Wyoming PAUL D. WELLSTONE, Minnesota JOHN ASHCROFT, Missouri BARBARA BOXER, California BILL FRIST, Tennessee ROBERT G. TORRICELLI, New Jersey LINCOLN D. CHAFEE, Rhode Island STEPHEN E. BIEGUN, Staff Director EDWIN K. HALL, Minority Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON NEAR EASTERN AND SOUTH ASIAN AFFAIRS SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas, Chairman JOHN ASHCROFT, Missouri PAUL D. WELLSTONE, Minnesota GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon ROBERT G. TORRICELLI, New Jersey ROD GRAMS, Minnesota PAUL S. SARBANES, Maryland CRAIG THOMAS, Wyoming CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut (II) VerDate 11-MAY-2000 15:20 Dec 05, 2000 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 67981 SFRELA1 PsN: SFRELA1 CONTENTS Page Barakat, Colonel Charbel, South Lebanon Army; coordinator of the Civilian Committees, South Lebanon Refugees in Israel ............................................... -

The Israeli Experience in Lebanon, 1982-1985

THE ISRAELI EXPERIENCE IN LEBANON, 1982-1985 Major George C. Solley Marine Corps Command and Staff College Marine Corps Development and Education Command Quantico, Virginia 10 May 1987 ABSTRACT Author: Solley, George C., Major, USMC Title: Israel's Lebanon War, 1982-1985 Date: 16 February 1987 On 6 June 1982, the armed forces of Israel invaded Lebanon in a campaign which, although initially perceived as limited in purpose, scope, and duration, would become the longest and most controversial military action in Israel's history. Operation Peace for Galilee was launched to meet five national strategy goals: (1) eliminate the PLO threat to Israel's northern border; (2) destroy the PLO infrastructure in Lebanon; (3) remove Syrian military presence in the Bekaa Valley and reduce its influence in Lebanon; (4) create a stable Lebanese government; and (5) therefore strengthen Israel's position in the West Bank. This study examines Israel's experience in Lebanon from the growth of a significant PLO threat during the 1970's to the present, concentrating on the events from the initial Israeli invasion in June 1982 to the completion of the withdrawal in June 1985. In doing so, the study pays particular attention to three aspects of the war: military operations, strategic goals, and overall results. The examination of the Lebanon War lends itself to division into three parts. Part One recounts the background necessary for an understanding of the war's context -- the growth of PLO power in Lebanon, the internal power struggle in Lebanon during the long and continuing civil war, and Israeli involvement in Lebanon prior to 1982. -

JM Weatherston

Northumbria Research Link Citation: Weatherston, Jack (2018) How the West has Warmed: Climate Change in the Contemporary Western. Doctoral thesis, Northumbria University. This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/39786/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html HOW THE WEST HAS WARMED: CLIMATE CHANGE IN THE CONTEMPORARY WESTERN J. M. WEATHERSTON PhD 2018 1 HOW THE WEST HAS WARMED: CLIMATE CHANGE IN THE CONTEMPORARY WESTERN JACK MICHAEL WEATHERSTON A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Northumbria at Newcastle for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Research undertaken in the Faculty of Arts, Design & Social Sciences OCTOBER 2018 2 Abstract This thesis will argue that the contemporary Western, in literature and film, has shown a particular capacity to reflect the influence of climate change on the specific set of landscapes, ecosystems and communities that make up the American West. -

HBO: Brand Management and Subscriber Aggregation: 1972-2007

1 HBO: Brand Management and Subscriber Aggregation: 1972-2007 Submitted by Gareth Andrew James to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, January 2011. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. ........................................ 2 Abstract The thesis offers a revised institutional history of US cable network Home Box Office that expands on its under-examined identity as a monthly subscriber service from 1972 to 1994. This is used to better explain extensive discussions of HBO‟s rebranding from 1995 to 2007 around high-quality original content and experimentation with new media platforms. The first half of the thesis particularly expands on HBO‟s origins and early identity as part of publisher Time Inc. from 1972 to 1988, before examining how this affected the network‟s programming strategies as part of global conglomerate Time Warner from 1989 to 1994. Within this, evidence of ongoing processes for aggregating subscribers, or packaging multiple entertainment attractions around stable production cycles, are identified as defining HBO‟s promotion of general monthly value over rivals. Arguing that these specific exhibition and production strategies are glossed over in existing HBO scholarship as a result of an over-valuing of post-1995 examples of „quality‟ television, their ongoing importance to the network‟s contemporary management of its brand across media platforms is mapped over distinctions from rivals to 2007. -

Lebanon's Political Dynamics

Lebanon’s political dynamics: population, religion and the region Salma Mahmood * As the Lebanese political crisis deepens, it becomes imperative to examine its roots and find out if there is a pattern to the present predicament, in examination of the past. Upon tracing the historical background, it becomes evident that the Lebanese socio-political system has been influenced by three major factors: the population demographic, regional atmosphere and sub-national identity politics. Though not an anomaly, Lebanon is one of the few remaining consociational democracies1 in the world. However, with the current political deadlock in the country, it is questionable how long this system will sustain. This article will take a thematic approach and begin with the historical precedent in each context linking it to the current situation for a better comprehension of the multifaceted nuclei shaping the country‟s turbulent course. Population Demographics Majority of the causal explanations cited to comprehend the contemporary religio-political problems confronting the Middle East have their roots in the imperialist games. Hence, it is in the post First World War French mandate that we find the foundations of the Lebanese paradigm. In 1919, the French decision was taken to concede the Maronite demands and grant the state of a Greater Lebanon. Previously, under the Ottoman rule, there existed an autonomous district of Lebanon consisting solely of Mount Lebanon and a 1914 population of about 400,000; four-fifth Christian and one-fifth Muslim. Amongst -

Seminario Sobre Documental Interactivo

SEMINARIO SOBRE DOCUMENTAL INTERACTIVO Prof. Arnau Gifreu La Casa del Cine/Curso 2009-2010 DISTINCIÓN Y ESTUDIO DE GENEROS SEGUN XAVIER BERENGUER: Documentales antropológicos expositivos: - Robert Flaherty - John Grierson Documentales antropológicos reflexivos: - Dziga Vertov Documentales antropológicos de observación: - Leacok - Pennebaker Documentals antropológicos reactivos: - Michael Moore Documentales fuera de linea: -The day alter trinity (J. Robert -Oppenheimer) -Immemory (Chris Marker) -Ann Frank House Documentales en linea: -J.B.Wiesner TIPOLOGIA DEL DOCUMENTAL SEGUN BILL NICHOLS 1. EXPOSITIVO 2. DE OBSERVACIÓN 3. INTERACTIVO 4. REFLEXIVO 1. DOCUMENTALES ANTROPOLÓGICOS EXPOSITIVOS: - ROBERT FLAHERTY - JOHN GRIERSON 2. DOCUMENTALES ANTROPOLÓGICOS DE OBSERVACIÓN: - LEACOK - PENNEBAKER 3. DOCUMENTALES ANTROPOLÓGICOS REFLEXIVOS: - DZIGA VERTOV 4. DOCUMENTALES ANTROPOLÓGICOS REACTIVOS: MICHAEL MOORE EVOLVING DOCUMENTARY GLORIANNA DAVENPORT MICHAEL MURTANGH Enlaces de interés: Pàgines de Xavier Berenguer – Documental Interactiu www.boschuniverse.org www.artmuseum.net www.theyrule.net www.becomingwoman.org www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/galileo www.nostranau.net www.abc.net.au/longjourney/australia www.witness.org www.oneworld.net 1. DOCUMENTALES ANTROPOLÓGICOS EXPOSITIVOS: - ROBERT FLAHERTY - JOHN GRIERSON ROBERT FLAHERTY (1884 – 1951) El documental explorador: Flaherty Robert Joseph Flaherty Nació en Iron Mountain, Michigan. un 16 de Febrero de 1884 y murió en Dummerston Vt. un 23 de Julio de 1951). Era hijo de un Ingeniero de minas y desde pequeño tuvo mucha relación con mineros e indios. Su padre se hizo explorador de nuevas tierras y a veces llevaba a Robert en sus exploraciones. En 1910 Flaherty inició su trayectoria de explorador en busca de yacimientos y en 1913 la persona que lo contrataba le sugirió que grabase su expedición. Así fue. -

Media Kit an Exclusive Television Event

MEDIA KIT AN EXCLUSIVE TELEVISION EVENT ABOUT SHOWTIME SHOWTIME is the provider of Australia’s premium movie channels: SHOWTIME, SHOWTIME 2 and SHOWTIME Greats. Jointly owned by four A HELL OF A PLACE TO MAKE YOUR FORTUNE MA Medium Level Violence Coarse Language of the world’s leading fi lm studios Sony Pictures, Paramount Pictures, Sex Scenes 20th Century Fox and Universal Studios, as well as global television distributor Liberty Media, the SHOWTIME channels are available on FOXTEL, AUSTAR, Optus, TransAct and Neighbourhood Cable. For further information contact: Catherine Lavelle CLPR M 0413 88 55 95 SERIES PREMIERE 8.30PM WEDNESDAY NOVEMBER 3 - continuing weekly E [email protected] showtime.com.au/deadwood In an age of plunder and greed, the richest gold strike in American history draws a throng of restless misfi ts to an outlaw settlement where everything — and everyone — has a price. Welcome to DEADWOOD...a hell of a place to make your fortune. From Executive Producer David Milch (NYPD BLUE) comes DEADWOOD, a new drama series that focuses on the birth of an American frontier town and the ruthless power struggle that exists in its lawless boundaries. Set in the town of DEADWOOD, South Dakota the story begins two weeks after Custer’s defeat at Little Big Horn, combining fi ctional and real-life characters and events in an epic tale. Located in the Black Hills Indian Cession, the “town” of DEADWOOD is an illegal settlement, a violent and uncivilized outpost that attracts a colorful array of characters looking to get rich — from outlaws and entrepreneurs to ex-soldiers and racketeers, Chinese laborers, prostitutes, city dudes and gunfi ghters. -

Still on the Road Session Pages: 1965

STILL ON THE ROAD 1965 CONCERTS, INTERVIEWS & RECORDING SESSIONS JANUARY 13 New York City, New York Studio A, Columbia Recording Studios, The 1st Bringing It All Back Home recording session 14 New York City, New York Studio A, Columbia Recording Studios, The 2nd Bringing It All Back Home recording session 15 New York City, New York Studio A, Columbia Recording Studios, The 3rd and last Bringing It All Back Home recording session 29 Springfield, Massachusetts Municipal Auditorium FEBRUARY 10 New Brunswick, New Jersey The State College, Rutgers Gymnasium 12 Troy, New York Troy Armory 17 New York City, New York WABC TV Studios, Les Crane Show MARCH 19 Raleigh, North Carolina Reynolds Coliseum 21 Ottawa, Ontario, Canada Capitol Theatre 26 Los Angeles, California Ciro's Le Disc, Hollywood 27 Santa Monica, California Civic Auditorium APRIL 9 Vancouver, British Columbia, Queen Elizabeth Theatre Canada 24 Seattle, Washington The Arena 26 London, England Arrival Area, London Airport 26 London, England Press Conference Room, London Airport, Short interview 27 London, England Savoy Hotel 27 London, England Savoy Hotel, Interview by Jack DeManio 27 London, England Savoy Hotel, press conference 30 Sheffield, England The Oval, City Hall, press conference 30 Sheffield, England The Oval, City Hall, soundcheck 30 Sheffield, England The Oval, City Hall MAY 1 Liverpool, England Odeon 2 Leicester, England De Montfort Hall 2 Leicester, England De Montfort Hall 3 or 4 London England A Hotel Room, Savoy Hotel 5 Birmingham, England Town Hall, backstage before -

Demographic Jihad by the Numbers

Demographic Jihad by the Numbers: Getting a Handle on the True Scope 2 June 2007 ©Yoel Natan HTML PDF (<2 MB) Author of the book Moon-o-theism I. Introduction A. Countering the Inevitable Charge of Islamophobia ► Case #1: A Pew Research Poll in 2007 Says 26% of Young Adult Muslim-Americans Support Suicide Bombing ► Case #2: Infidels Supposedly Have Nothing to Fear from Muslims, Yet Muslims Inexplicably Fear Being Takfired, That Is, Being Declared Infidels B. Demographic Jihad Explained C. Why This Study Is Important ► The Size of the Minority of Muslims and the Quality of Life Index D. Arriving at Accurate Demographic Snapshots and Projections E. The Politics of Demographic Numbers II. Global Demographics and Projections Countries discussed in some detail (if a country is not listed here, it likely is mentioned in passing, and can be found using the browser Search function): Afghanistan Africa Albania Algeria Argentina Australia Austria Azerbaijan Bangladesh Belgium Belize Benin Bosnia-Herzegovina & the Republika Srpska Britain (United Kingdom) Canada Chechnya China Cote d'Ivoire (Ivory Coast) Cyprus Czech Republic Denmark East Timor Egypt Eritrea Estonia Ethiopia Europe France French Guiana Germany Global Greece Greenland Guyana Horn of Africa/Somalia India Indonesia Iran Iraq Ireland & North Ireland (UK) Islamdom Israel Italy Japan Jordan Kosovo Lebanon Macedonia Malaysia Mexico Mideast Mongolia Montenegro Morocco Netherlands Nigeria North America Norway Oman Pakistan Palestine (West Bank and Gaza) Philippines Russia Saudi Arabia Serbia Singapore South Africa South America South Asia Spain Sri Lanka Sudan Suriname Sweden Switzerland Syria Tajikistan Thailand Tri-Border Region, aka Triple Frontier, Trinidad & Tobago Islands Turkey Ukraine United States Western Sahara Yemen Note: For maps and population information, see Yoel Natan’s “Christian and Muslim Demographics,” May 2007 PDF (>8MB).